Why Was Cotton ‘King’?

Its beautiful bolls,

And bales of rich value, the Master controls.

Of “mud-stills” he prates, and would haughtily bring

The world to acknowledge that “Cotton is King.”

–The Gospel of Slavery, by “Iron Gray,” [Abel C. Thomas] 1864.

The most commonly used phrase describing the growth of the American economy in the 1830s and 1840s was “Cotton Is King.” We think of this slogan today as describing the plantation economy of the slavery states in the Deep South, which led to the creation of “the second Middle Passage.” But it is important to understand that this was not simply a Southern phenomenon. Cotton was one of the world’s first luxury commodities, after sugar and tobacco, and was also the commodity whose production most dramatically turned millions of black human beings in the United States themselves into commodities. Cotton became the first mass consumer commodity.

Understanding both how extraordinarily profitable cotton was and how interconnected and overlapping were the economies of the cotton plantation, the Northern banking industry, New England textile factories and a huge proportion of the economy of Great Britain helps us to understand why it was something of a miracle that slavery was finally abolished in this country at all.

Let me try to break this down quickly, since it is so fascinating:

Let’s start with the value of the slave population. Steven Deyle shows that in 1860, the value of the slaves was “roughly three times greater than the total amount invested in banks,” and it was “equal to about seven times the total value of all currency in circulation in the country, three times the value of the entire livestock population, twelve times the value of the entire U.S. cotton crop and forty-eight times the total expenditure of the federal government that year.” As mentioned here in a previous column, the invention of the cotton gin greatly increased the productivity of cotton harvesting by slaves. This resulted in dramatically higher profits for planters, which in turn led to a seemingly insatiable increase in the demand for more slaves, in a savage, brutal and vicious cycle.

Now, the value of cotton: Slave-produced cotton “brought commercial ascendancy to New York City, was the driving force for territorial expansion in the Old Southwest and fostered trade between Europe and the United States,” according to Gene Dattel. In fact, cotton productivity, no doubt due to the sharecropping system that replaced slavery, remained central to the American economy for a very long time: “Cotton was the leading American export from 1803 to 1937.”

What did cotton production and slavery have to do with Great Britain? The figures are astonishing. As Dattel explains: “Britain, the most powerful nation in the world, relied on slave-produced American cotton for over 80 per cent of its essential industrial raw material. English textile mills accounted for 40 percent of Britain’s exports. One-fifth of Britain’s twenty-two million people were directly or indirectly involved with cotton textiles.”

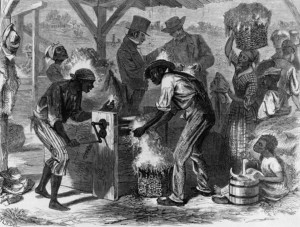

“First cotton gin” from Harpers Weekly. 1869 illustration depicting event of some 70 years earlier by William L. Sheppard. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs division)

And, finally, New England? As Ronald Bailey shows, cotton fed the textile revolution in the United States. “In 1860, for example, New England had 52 percent of the manufacturing establishments and 75 percent of the 5.14 million spindles in operation,” he explains. The same goes for looms. In fact, Massachusetts “alone had 30 percent of all spindles, and Rhode Island another 18 percent.” Most impressively of all, “New England mills consumed 283.7 million pounds of cotton, or 67 percent of the 422.6 million pounds of cotton used by U.S. mills in 1860.” In other words, on the eve of the Civil War, New England’s economy, so fundamentally dependent upon the textile industry, was inextricably intertwined, as Bailey puts it, “to the labor of black people working as slaves in the U.S. South.”

If there was one ultimate cause of the Civil War, it was King Cotton — black-slave-grown cotton — “the most important determinant of American history in the nineteenth century,” Dattel concludes. “Cotton prolonged America’s most serious social tragedy, slavery, and slave-produced cotton caused the American Civil War.” And that is why it was something of a miracle that even the New England states joined the war to end slavery.

Once we understand the paramount economic importance of cotton to the economies of the United States and Great Britain, we can begin to appreciate the enormity of the achievements of the black and white abolitionists who managed to marshal moral support for the abolition of slavery, as well as those half a million slaves who “marched with their feet” and fled to Union lines as soon as they could following the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media