Who Really Invented the ‘Talented Tenth’?

Just about everybody who knows anything about black history and/or Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois knows that one of the most important concepts of the many that he defined was “the Talented Tenth.” Many of us even committed to memory the first two sentences of perhaps his most famous essay, published in 1903 in a book called The Negro Problem, and edited by Du Bois’s nemesis, Booker T. Washington: “The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst, in their own and other races.”

These sentences were effectively a throw-down against Washington’s strident advocacy of industrial training as the ideal curriculum for the daughters and sons for the former slaves, rather than a classical liberal arts education, the sort of education that Du Bois had received at Fisk and then at Harvard. So, for Du Bois, how Negroes should be educated, and Washington’s position about it, was quite personal.

Well, if you guessed that W.E.B. Du Bois was the author of the concept of “the Talented Tenth,” you would be wrong! As my colleague Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham first noted in her book, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880 – 1920, the term was actually invented by a white man, Henry Lyman Morehouse (the man for whom the great Morehouse College was named), seven years before Du Bois popularized it. In an essay by that very title first published in April 1896 in the Independent magazine, Morehouse coined the term and defined it in this way: “In the discussion concerning Negro education we should not forget the talented tenth man. An ordinary education may answer for the nine men of mediocrity; but if this is all we offer the talented tenth man, we make a prodigious mistake.” Why? Because, Morehouse continues, “The tenth man, with superior natural endowments, symmetrically trained and highly developed, may become a mightier influence, a greater inspiration to others than all the other nine, or nine times nine like them.”

Obviously concerned that his argument would appear to be elitist, which it nakedly and unapologetically was — like Du Bois’ elaboration of it seven years later — Morehouse was quick to add that he was not unmindful of the importance of the contributions of the other so-called “nine-tenths”: “Without disparagement of faithful men of moderate abilities, it may be said that in all ages the mighty impulses that have propelled a people onward in their progressive career, have proceeded from a few gifted souls … men of thoroughly disciplined minds, of sharpened perceptive faculties, trained to analyze and to generalize; men of well-balanced judgments and power of clear and forceful statement.” The talented tenth man, Morehouse concludes, “is an uncrowned king in his sphere.”

A Battle Rooted in “Compromise”

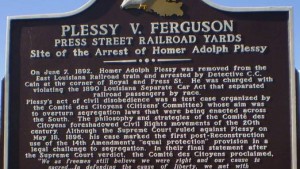

What a powerful, if quite idealistic, brief for a black liberal arts education Morehouse gave. It is no accident that he published this essay just a few months after Booker T. Washington’s famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech. That address was delivered at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta the previous September, at the height of the Jim Crow era, less than a year before the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision was handed down on May 18, 1896, cementing “separate but equal” as the law of the land (until that decision was overturned by the court in Brown v. Board in 1954). In this speech, which was widely heralded throughout the country and which was called the “Atlanta Compromise” because Du Bois mockingly dubbed it as such, Washington stressed, among other things, the importance of industrial or vocational curricula over a college education for black people.

Morehouse, without naming Washington, was taking Washington’s position head on: “I repeat that not to make proper provision for the high education of the talented tenth man of the colored people is a prodigious mistake. It is to dwarf the tree that has in it the potency of a grand oak. Industrial education is good for the nine; the common English branches are good for the nine; but that tenth man [like Du Bois, whom he doesn’t name but of whom he is clearly thinking, and unlike Washington, who he hints is actually a prime example of those “self-made men, so-called, whose best powers were evoked by rare opportunities”] ought to have the best opportunities for making the most of himself for humanity and for God.”

Note that Washington — in possibly the most famous and widely distributed speech that a black person had given before Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963 — had just a few months before declared in Atlanta, to the delight of Southern segregationists who hailed him as a prophet, that “we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful.” And wait for Washington’s punch line: “No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities.”

Clearly, Morehouse was firing the opening salvo at Washington’s concept of the proper way to educate a Negro, and in 1903 Du Bois would fire the second. And just as clearly, Du Bois took Washington’s attack on the role of the liberal arts in Negro education personally, especially his line that “The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house.” In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois would signify upon Washington’s comment by publishing a short story, “Of the Coming of John,” which features his black protagonist paying five dollars to attend a performance of Lohengrin, Richard Wagner’s famous opera, only to be removed from his seat because a white man objects to being seated next to him.

Did Lincoln Plant the Seed?

What strikes me as fascinating about Morehouse’s and Du Bois’ concept of a supposedly elite 10 percent of “the race” is that it accords almost exactly with the size of the Free Negro population in the 1860 census: 11 percent of the African-American community was composed of Free Negroes on the eve of the Civil War (and quite surprisingly far more of them lived in the South (258,346) than in the Northeast (155,983), but that’s the subject of another column). And it was this group of freed persons to whom President Abraham Lincoln was referring when he announced, in the last speech of his life, that he advocated giving “the elective franchise” to “the very intelligent [colored man], and on those who serve our cause as soldiers,” who numbered about 200,000.

If we add the number of free black men with the number of black soldiers, it’s easy to see that Abraham Lincoln effectively introduced the notion of a privileged “talented tenth” within the race who would be accorded more rights than the remaining nine-tenths, the 3.95 million slaves who would really only be freed by the ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865. So perhaps we should give Lincoln the credit for inventing the concept!

Despite the narrow scope and elitism of Lincoln’s proposal, how radical an idea was this in an America that had just suffered massive losses from a civil war that undeniably was fought to end black slavery? Standing on the grounds of the White House listening to the president’s speech that day, April 11, 1865, was a man named John Wilkes Booth. When he heard Lincoln say that he wanted to give even some black men the right to vote, Booth was heard to remark, “That means nigger citizenship. That is the last speech he will ever make.” Four days later, Booth assassinated Lincoln. The 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which extended to all black men the right to vote, would be ratified on Feb. 3, 1870, five years after Lincoln’s death.

Even more curiously, a month after Lincoln’s 1865 speech, the black Republican newspaper in New Orleans foreshadowed the concept of the Talented Tenth in an editorial it published as early as May 18, when it noted that “the [black] poor … are nine-tenths of the colored population.” So it’s clear that concept of the Talented Tenth had multiple authors before Du Bois publicized it in 1903.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media