It Takes Courage to be Weak ~ Lesson Activities

Lesson Activities

INTRODUCTORY ACTIVITY

- Divide the class into groups of 3-5 students and distribute the In Your Own Words Student Organizer to each student. Explain that the organizer asks them to read several famous quotations and to rewrite them in their own words, distilling the main points of each statement. Ask the students to work in groups to complete Part I of the organizer, deciphering the quotations and reinterpreting them in their own words. They should write down their group’s reinterpretation below each quote. (You may either have the whole class rewrite all three quotations, or divide them among the different groups in the class).

- Reconvene to discuss the class’ interpretations of the quotations and to discuss any discrepancies that emerged in the class’ renditions. If the quotations were divided among different groups in the class, have the students complete any blank sections of Part I with the help of the other groups.

- Ask the class to continue to Part II of the organizer, where they compare the commonalities between the three quotations.

- Review the students’ answers for Part II orally. Make sure the students understand that all three quotations have to do with justice and social change.

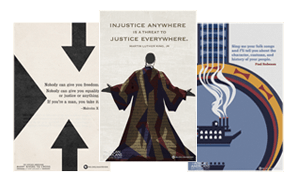

- They speak to factors that are important to struggles against injustice: to examine the root causes of the injustice (Baker), to raise community consciousness of injustice by standing up against unjust laws (King), and to persist in taking action, no matter how small, toward justice (Gandhi). All three authors were important activists for social change. If needed, help the class define “activist” (a person who actively engages in efforts to achieve social or political change).

- Briefly discuss the authors and the struggles for social change that they were most famously involved in (King and Baker: Civil Rights for African Americans; Gandhi: India’s freedom from British colonial rule).

LEARNING ACTIVITY

- Explain that one powerful form of activism, that was extremely important to the Civil Rights struggle of the 1950s and 1960s in the US, was “non-violent protest.” In this activity, students will learn more about the philosophy and method behind this strategy of achieving social change.

- Distribute the Non-Violent Protest Student Organizer to each student. Go over the instructions as a class (you may also want to make a list of the actions/goals on the board as you go along).

- Before viewing the first video clip, “Rosa Parks,” probe the students on who Rosa Parks was and why she was famous (she occupied a seat in a whites-only section of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955). Ask the students if they think Rosa Parks had prepared herself to occupy the seat, and if so, how she might have gone about doing so. (Accept all answers.)

- Play Video Segment 1, “Rosa Parks.” After the segment has concluded, review the question you posed (in fact, Rosa Parks had been working with civil rights activists for many years, and was carefully chosen for this role. She had also undergone training before taking her stand on the bus). The students should begin filling out their “Non-Violent Protest” Student Organizer, e.g. by listing the action of “occupying a whites-only seat on a segregated bus” with the (immediate) goal of bringing attention to the injustice of segregation, and the (ultimate) goal of desegregating the buses. They may also list boycotts.

- Before playing video segment 2, “Ruby Bridges,” explain that even though laws banning segregation had been passed, it sometimes required non-violent protest to make sure that those laws were enacted. If the students have previously studied the Brown v. Board of Education settlement, you may ask them to recall this landmark Supreme Court decision. Play “Ruby Bridges” and have the students continue filling out their organizer. (NOTE to teachers: this segment ends with archival news footage of a white woman explaining to a news reporter that “we don’t want n****s in this school – this is a nice school.” You may wish to follow the viewing of this segment with a discussion of the entrenched attitudes and stereotypes that civil rights activists, including six-year-old Ruby Bridges, were up against when they tried to desegregate schools and other institutions. For more on this topic, see “Who Was Jim Crow?”.

- Proceed to Video Segment 3 “Preparing for the Sit-In.” Before viewing the video, review the concept of a Sit-In and help students understand that it consists of non-violently (although sometimes unlawfully) occupying a particular establishment to draw attention to a cause. Play the segment. Afterward, lead a discussion on the philosophy of nonviolence – is this strategy also “non-confrontational”? Is it aggressive? Ensure that the students understand that the philosophy of non-violent protest requires only that the protesters remain nonviolent, not the members of the establishment’s status quo (e.g. business owners, police, and the general public). In fact, the actions of non-violent protesters often knowingly invited violence; non-violent passive resistance was actually seen by other civil rights leaders as an aggressive and confrontational strategy. Briefly discuss the mental and emotional strength that was evident among the protesters in the video.

CULMINATING ACTIVITY

- In class or as homework, the students will explore the mental, physical, and emotional challenges inherent to the strategy of non-violent passive resistance. Distribute the Sit-In Student Organizer to the students (along with the “Nonviolence and Racial Justice” handout, if the students are not going online to read it).

- Go over the instructions. First, the students will read excerpts from a 1957 article written by Martin Luther King, Jr. They should underline phrases that convey the philosophy of non-violent passive resistance. With this manifesto as a background, the students will imagine that they are one of the students taking part in the 1960 Nashville lunch counter sit-ins. They will write a first person account of their role in the event, as if they were describing the experience in a letter to a close friend. How did they manage to stay passive in the face of the threats, violence, and hostility shown to them?

- Collect the “Sit-In” letters to assess student learning.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media