African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement ~ Lesson Activities

Lesson Activities

INTRODUCTORY ACTIVITY

1. Divide the class into seven groups and allow 5 minutes for them to brainstorm a list of 5 key events or turning points in African-American history. After 5 minutes have passed, have groups take turns reading their list to the class, and compile them on the blackboard or whiteboard, noting which events are mentioned multiple times. (Answers will vary, but will probably include familiar touchstones of African American history, such as, the Emancipation Proclamation, Rosa Parks’ refusal to move to the back of the bus, Brown v. Board of Education, Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream Speech,” and the election of Barack Obama as president.)

2. Ask students how many of the key events and turning points they’ve compiled occurred before 1970. (Answers will vary, but most groups will have focused on events prior to 1970.) Ask students why they think this might be. (Accept all answers, but suggest that the traditional narrative of African American history has largely been defined by the political struggle for civil rights which culminated in the 1960s.)

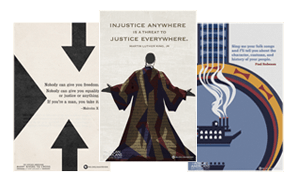

3. Write the following quote on the blackboard or whiteboard: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Ask who most famously made this observation, and to what was he referring. (Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; he was referring to what he believed to be the slow but inevitable progress of the civil rights movement.) Ask students how many of the key events and turning points in African American history they compiled are points on King’s “arc of the moral universe,” and what they each signify. (Answers will vary, but should include how slavery was America’s original sin, how the Civil War was a test of our ideals, how the civil rights movement was our great moral enlightenment, and how the election of Barack Obama was a redemptive political triumph over racism.) Ask students what these intersections between key events in African-American history and points on King’s “arc of moral universe” reveal about the narrative of African-American history. Explain that a primary role of African-American history in the context of American history more generally has been to provide an index of the nation’s moral progress.

4. Explain that this lesson will focus on the different, often divergent, and increasingly visible currents of African American life in the wake of the civil rights movement. Distribute the “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer and explain that each row on the organizer corresponds to one of these cultural currents, each of which will be described in a video excerpt from The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross. Instruct students to complete their organizers individually throughout the remainder of the lesson for later use in the Culminating Activity. [Note to students that the spaces provided on their Student Organizers is notional and may not be adequate for their responses, which should be kept on a separate sheet of paper.]

LEARNING ACTIVITIES

[NOTE: As an alternative to the in-class Learning Activities outlined here, the “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer may be used as an independent guided activity for students to complete, either individually or in groups, using the video segments available online.]

1. Ask students how much they think white Americans knew about African-American culture in the 19th century. (Most probably knew very little, as individual and institutional racism precluded much direct experience with the black portion of an often literally segregated society.) Point out that this was true for many of the more enlightened whites who had worked for the advancement of African Americans–notably Abraham Lincoln himself. Further suggest that given their near-complete absence from wider American culture and media, even many African Americans themselves would have lacked a larger sense of African American culture beyond their own immediate experience.

2. Ask students how African Americans’ cultural profile had changed by the second half of the 20th century. (African Americans had by 1950 definitively arrived on the American cultural stage–with jazz already being regarded as the greatest American art form.) Explain that despite such progress, African Americans had yet to make it into most American living rooms. Ask what technological development helped change this. (Television.) What were among the first non-performance images of African Americans broadcast on television? (Images of the first African American students to desegregate schools in the South.) Explain that these images of desegregation–and of the often violent white response to it–helped build wider sympathy for African Americans living in the Jim Crow South and build support for the civil rights movement.

3. Explain that as the 1960s progressed, the media remained, on the whole, a critical ally of the civil rights campaign, helping to promote landmark legislation like the 1965 Civil Rights Act and make Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. a household name. Ask students what happened in 1968 that changed the entire civil rights landscape. (Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated.)

4. Provide a focus question for the first video segment by asking students to be watching for the effects King’s assassination had on the African Americans who had followed his lead in the civil rights movement. Play “Black Power: Demanding a Brilliant Future.” Pause the video after Kathleen Neal Cleaver says “That’s where the Black Panther party came in…it’s for the people who want to bring about change.” Review the focus question: what effects did King’s assassination have on the African Americans who had followed his lead in the civil rights movement? (Overcome with anger and despair at the murder of their leader, African Americans took to the streets, burning down their own neighborhoods in a series of nationwide race riots.) In this context, what was the appeal of the new Black Panther party? (African Americans who had become disillusioned with the non-violence advocated by King were drawn to the Black Panther’s message of armed resistance and revolution against a society which may have granted them political rights, but not real political power.) Provide a focus for the remainder of the segment by asking students to be watching for the meaning of the Black Panther slogan “Guns and Butter.” Resume playing video to the end of the segment.

5. Review the focus question: what did the Black Panther slogan “Guns and Butter” mean? (The “guns” referred to the armed patrols undertaken by the Black Panthers to discourage police brutality and other infringements of their rights, while “butter” referred to community aid programs undertaken by and for African Americans.) Ask students what they think such slogans suggested about the Black Panthers’ faith in the civil rights movement to deliver freedom and equality. (They had lost faith in–and patience with–the civil rights movement.) Suggest that this loss of faith extended to the United States of America more generally, and that another dimension of the Black Power movement was a newfound cultural identification with a very old homeland. Allow students a few minutes to complete the first row of their “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer.

6. Provide a focus for the next video segment by asking students what Maulana Karenga means when he says he invented the African American holiday of Kwaanza to help “decolonize the mind.” Play “Black is Beautiful: Afrocentricity.” Pause the video after Maulana Karenga says, “It became a movement holiday–and as the movement grew, it grew.” Review the focus question:

What does Maulana Karenga mean when he says he invented the African-American holiday of Kwaanza to help “decolonize the mind?” (He is saying that he created Kwaanza to help African Americans free themselves from the culture of their white oppressors and reconnect with Africa.) Provide a focus for the remainder of the clip by asking students to be watching for other manifestations of the “cultural revolution” advocated by Karenga and others. Resume playing video to the end of the segment.

7. Review the focus question: What were some other manifestations of the “cultural revolution” advocated by Karenga and others? (African Americans embracing “natural” –or “Afro” –hairstyles as part of the “Black is Beautiful” movement, an increase of African American characters on television shows, and a newfound sense of pride and self-love among African Americans seeing “blackness” as an embodiment of cool.) Ask students why they think Afrocentricity was promoted. (Accept all answers, but suggest that the movement was ultimately more about helping African Americans create their own identity here in America than it was about connecting with the actual African continent.) Allow students a few minutes to complete the second row of their “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer.

8. Provide a focus for the next video by asking students how the rising profile of African Americans in mainstream American media helped enable their real-life integration into the great American middle class. Play “The Rise of the Black Middle Class.” Pause the video right after Professor Gates says to William Julius Wilson that “You and I are prime examples [of affirmative action]” and Wilson responds, “Precisely.” Review the focus question: how did the rising profile of African Americans in mainstream American media help enable their real-life integration into the great American middle class? (Programs like Soul Train made African American culture truly national and accessible to everyone with a television set.) Explain that just as the 1950s and 1960s had seen African Americans politically integrated into American society, the 1970s witnessed a cultural integration of “blackness” into mainstream America which made African Americans seem less threatening to most whites. Provide a focus for the remainder of the video segment by asking students why the FBI still insisted on called the Black Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” Resume playing video to the end of the segment.

9. Review the focus question: Why did the FBI call the Black Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country?” (According to Maulana Karenga, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover “feared us in our unity; the potential of a unified black movement, self-conscious and armed.”) Ask students if the Blank Panthers were universally supported by the African-American community. Who may not have wanted to be associated with the Black Panthers and why? (Accept all answers, but suggest that Hoover’s fears of a unified black movement were ill-founded.) Allow students a few minutes to complete the third row of their “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer.

10. Provide a focus for the next clip by asking what the organizers of the first National Black Political Convention in 1972 hoped to highlight and achieve. Play “The Limits of Rights: Economic Injustice.” Review the focus question: What had the organizers of the first National Black Political Convention in 1972 hoped to highlight and achieve? (They had hoped to highlight ongoing economic hardships among African Americans, which the gaining of new political rights had done little to alleviate.) Why does Vernon Jordan think it was difficult for them to arrive at a consensus about how to address the problem? (Consensus, he observes, is an unrealistic expectation to have for any large group of people; to expect it of African Americans as a whole is to ignore their diversity.) How does Angela Glover Blackwell describe that diversity in the African American community? (As “a tale of three cities”–the highly successful few, the aspiring middle class, and the poor majority.) Ask students how the poverty of the urban black poor was, in Blackwell’s words, “worse than the poverty that preceded it.” (The deindustrialization of America’s cities left the urban African American poor stranded, without jobs, hope, or even a connection to their own middle class, who had fled with the white middle class to the suburbs.) Ask students what social ills such conditions create. (A breakdown of family and social cohesion, substance abuse, and crime.) Allow students a few minutes to complete the fourth row of their “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer.

11. Provide a focus for the next video segment by asking what, according to Michelle Alexander, was the real travesty and tragedy of the War on Drugs declared by President Reagan in the 1980s. Play “Casualties of the War on Drugs.” Review the focus question: according to Michelle Alexander, what was the real travesty and tragedy of the War on Drugs declared by President Reagan in the 1980s? (She asserts that the War on Drugs was effectively a war on inner-city African American youth, which over-aggressively criminalized an entire generation rather than addressing the underlying social and economic conditions which had led to widespread drug abuse in the first place.) Ask how “get tough” policies worsened rather than improved the plight of drug and gang-ravaged inner cities. (Mandatory sentencing laws punished drug offenders far beyond reason, filling prisons beyond capacity and making them an “extension of the [African American] community”) Allow students a few minutes to complete the fifth row of their “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer.

12. Provide a focus for the next video segment by asking students what rapper Chuck D means when he describes rap as “Black America’s CNN.” Play “Fighting the Power: Hip Hop.” Pause the video after Chuck D says “it was able to give direct commentary on what was going on.” Review the focus question: What does rapper Chuck D means when he describes rap as “Black America’s CNN”? (Rap was the only medium poor African American inner-city youth had in which to express their frustration and document the reality of their lives.) Ask students what similarities and differences they see between the Black Power movement of the 1970s and Chuck D’s calls with Public Enemy to “Fight the Power.” (Accept all answers, but suggest that the original Black Power movement was championing an ascendant African American culture, fueled by fresh political successes and a vision of a “brilliant” future; Chuck D and his peers in the 1980s, on the other hand, were calling for an almost desperate resistance against almost overwhelming white authority. In other words, the rhetorical “power” had shifted from African Americans themselves back to their oppressors.) Provide a focus for the remainder of the clip by asking why the Mayor of Los Angeles called for people to tune into the final episode of The Cosby Show during the 1992 Rodney King riots. Resume playing the video segment through to the end.

13. Review the focus question: why did the Mayor of Los Angeles call for people to tune into the final episode of The Cosby Show during the 1992 Rodney King riots? (It was an appeal for both blacks and whites to remember their common affection for a fictional African American family firmly based in the black middle class.) Why might such a call have failed to resonate with many of the rioters? (The prosperous characters on The Cosby Show represented “normalcy” to only two of the three African American “cities” enumerated earlier by Angela Glover Blackwell: the highly successful elite and the aspiring middle class, neither of whom were the ones rioting.)

14. Ask students if they think circumstances have changed much for poor inner-city African Americans since the Rodney King riots over 20 years ago. (Accept all answers, but suggest that many face the same challenges in escaping what has become a near-permanent urban underclass.) Allow students a few minutes to complete the sixth row of their “Many Currents: African-American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer.

15. Provide a focus for the final video segment by asking what Barack Obama’s former minister, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, was condemning immediately prior to making his infamous statement “God damn America.” Play “Yes We Can: Obama.” Review the focus question: what was Barack Obama’s former minister, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, condemning immediately prior to making his infamous statement “God damn America?” (He was condemning the War on Drugs. Like Michelle Alexander, Wright blames the government for the availability of drugs, the mass incarcerations, and the mandatory sentencing laws which have devastated African American communities.) Ask students which of the “three cities” they think Wright and his congregation inhabit. (Accept all answers, but suggest that Wright transcends easy categorization by preaching the angry politics of the African American poor to a relatively elite congregation.) Ask students if they think the same could be said for Obama himself. (Accept all answers, but point out that Obama is essentially a middle class, half-white African American who inspired people across traditional divides of race and class to believe that America could be a more perfect union by electing an individual who didn’t neatly fit into any one demographic.) Allow students a few minutes to complete the seventh row of their “Many Currents: African American Histories Since the Civil Rights Movement” Student Organizer.

16. Have students review the key events they listed during the Introductory Activity and compare them with the events they just examined. Ask students what the defining points in the decades since the civil rights movement suggest about the nature of African American culture more recently. (Answers will vary, but should include the observations that African Americans history has become a) more divergent, as the elite and the middle class have pulled away from the poor; and b) more visible, as African-American culture has been integrated into the mainstream.) Have students compare their answers with the classic narrative of African-American history discussed at the beginning of the lesson.

17. Explain that one of the challenges Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. faces as a preeminent scholar and historian of African American history is to deconstruct that history’s grand heroic narrative, respecting and celebrating the diversity of African Americans who are not, and have never been, a monolithic entity. He addresses this challenge explicitly in “A More Perfect Union” –the final episode of the PBS series The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross–which focuses on African-American history from the late 1960s to the present day.

CULMINATING ACTIVITY

1. Have students return to the seven groups into which they were divided for the Introductory Activity. Assign each group one of the Cultural Currents outlined on their Student Organizers and described in the corresponding video excerpts from The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross. As either homework or an in-class activity, have each group further research and discuss their assigned Cultural Current, adding to the responses on their Student Organizers. Additionally, have each group consider the following questions:

- Did their assigned Cultural Current help or hinder African Americans across the “many rivers” of their journey as a people? In what respects may it have done both?

- How was their assigned Cultural Current impacted or influenced by the others discussed in the lesson? How did it impact or influence the others?

- How have media representations of this current differed? Have they been positive or negative? How have they evolved over time?

- What is the legacy of this current in the African-American experience of today?

2. Have groups share their responses with the class, and encourage discussion among students.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media