Who Were the African Americans in the Kennedy Administration?

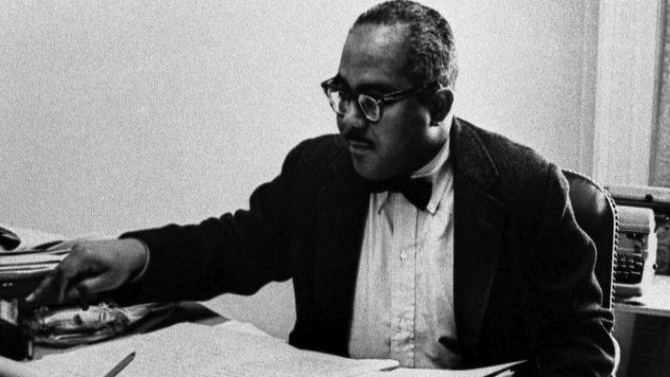

Andrew T. Hatcher, associate White House press secretary, the first black man to hold the No. 2 communications spot in the White House, behind his longtime political compatriot, Pierre Salinger. Photo by Abbie Rowe. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library And Museum, Boston.

“I regard the death of President Kennedy as the greatest tragedy that has befallen America since the assassination of Civil War President Abraham Lincoln,” declared a grief-stricken John H. Sengstacke, publisher of the Chicago Defender, hours after the 35th president was gunned down at 46 while riding in an open limousine beside the first lady. John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas happened 50 years ago this Friday. Speaking to his black readership, Sengstacke added, “Kennedy’s tragic ending is [also] the greatest blow that the Negro people has sustained since the demise of the great Emancipator.”

Jackie Robinson, the first black major-leaguer and a proud Republican who had supported Richard Nixon for president in 1960, contributed to the outpouring. “It’s hard for any of us to imagine even the tragedy that has hit,” he was quoted in the Defender. Drawing a parallel to black civil rights leader Medgar Evers, who had only been shot and killed outside his Mississippi home the previous June, Robinson noted, “Each of these gentlemen … desired a better America,” and even if Kennedy had “needed prodding” in advancing civil rights, “we all admired and respected him.”

Striking to me in going back to the immediate coverage of the Kennedy assassination is how quickly African Americans elevated him to sainthood. Just a few months prior, he had been lukewarm on the March on Washington (worried as he was about a backlash against the civil rights bill he had, at last, proposed in a televised address from the Oval Office on June 11 after sending in the National Guard to carry out a federal court-order desegregating the University of Alabama). Perhaps that sense of nuance—of distinctions among events so close in time—is what comes with the advance of years between my hearing the devastating news as a 13-year-old student in Mrs. Houchins’ geography class in Piedmont, W.V., and reflecting on it as a professor of 63 who has just completed a six-hour series for PBS on the 500-year history of the African American people, (Much of that history was spent making do while waiting for lawmakers to act, as you will see in Episode 5, covering the civil rights movement. It airs tomorrow night and is fittingly titled “Rise!”)

Don’t get me wrong: JFK is one of my favorite presidents. Yet I, like many, am aware of how much he evolved on civil rights, at least when it came to confronting the Southern Democrats in his party in the House and Senate.

“To some, he was slow to begin on his promise when he took office,” George Barbour wrote in the Pittsburgh Courier five days after the slain president had been buried in Arlington National Cemetery, the same cemetery in which Medgar Evers was buried. “However, to this reporter,” Barbour added, “he [JFK] never wavered and in appointments, speeches, application of presidential power, secured direct benefits for the Negro unparalleled in modern history, and this strengthened the character of a great country.” JFK was, if anything, a Cold Warrior aware of America’s standing in the world, of the need to lead “a new generation of Americans” toward what he famously called “the New Frontier.” But another Lincoln?

Indeed, Enoc Waters wrote in the Philadelphia Tribune on Nov. 26, 1963, “In spite of occasional criticism of his civil rights actions and legislative proposals, the thirty-fifth President of the United States was held in warm affection by all Negroes” (despite the fact that, on the day of his assassination, black Republicans were gathered in Cleveland for a political strategy session) so that the only presidents who could be fairly be compared to him were “Lincoln” and that other monogrammed man, “FDR.” The great civil rights attorney Constance Baker Motley agreed, telling the National Council of Women of the United States on Dec. 1, 1963, according to the Atlanta Daily World: JFK was “the greatest presidential advocate of equal rights this century has heard,” and there was only a century exactly separating his murder and the original Emancipation Proclamation Lincoln had issued before his assassination at the climax of the Civil War.

The mourning rites of those four November days in 1963—the shock, the arrival of the body in Washington, the lying in state, the Oswald murder, the funeral procession—certainly etched this image of Kennedy as the second coming of Lincoln in American minds. Whereas the late president had complained about the lack of black faces in the U.S. Coast Guard Academy honor guard at his inaugural parade, at his funeral, there were, Dan Day noted in a column appearing in the Philadelphia Tribune on Nov. 26, two “dark-skinned” military personnel in the eight-man detail “clearly in view at all times about the coffin.”

“Clearly in view”—that was the point, I’ve come to realize, the brilliance of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s stagecraft. A noted devotee of Broadway musicals, including Camelot, of course, JFK personally may have opposed discrimination as a moral matter; but, when it came to politics, he was a pragmatist who balanced his cautious legislative approach with a commitment to advance the symbols of desegregation and diversity in and around the White House, his Camelot. Stagecraft was something he, like FDR before him, made part of the modern presidency, and it’s something we take for granted today. On one hand, to keep Southern Democrats like Sen. Richard Russell of Georgia in the fold, he gave in on appointing their judges in the South. At the same time, to keep black voters in the North on his side, he went out of his way to see that talented black professionals, especially black newspapermen, were hired to get the message out to their readers that they—and the message—would be “clearly in view.”

“But the Cake Was Already Made”

The success of JFK’s public relations strategy rested on the abilities of his advisors. They included a few prominent blacks, who charted his segmented outreach efforts. While top Kennedy surrogates soft-pedaled his civil rights record in the South (there were few blacks who could vote there anyway in 1960), these black strategists targeted specific messages to black voters. It was a “strategy of association,” Nicholas Andrew Bryant writes in his valuable 2006 book, The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality. The key to their strategy: black talent and a black press committed to showcasing it.

The man the Kennedy team recruited to lead the charge was the long-time former editor of the Chicago Defender, Louis E. Martin, whom the Washington Post once called “ ‘the godfather of black politics.’ ” He was the eventual advisor of three sitting presidents, and a “well-versed representative of the black protest tradition,” with strong ties to labor, as Alex Poinsett writes in his 1997 biography, Walking With the Presidents: Louis Martin and the Rise of Black Political Power.

Back in the 1930s and ‘40s, Martin had helped turn Detroit Democratic in support of FDR’s New Deal as editor of the Michigan Chronicle. In joining the Kennedy campaign, he, along with black Washington attorneys Frank Reeves and Marjorie Lawson, customized JFK’s image for their friends at leading black newspapers across the country. After all, Martin had helped found the National Newspaper Publishers Association in 1940.

It was a two-pronged attack far more sophisticated than the Nixon people had calculated. While Kennedy toned down his message in the mainstream white papers (and had Lyndon Johnson campaign for him in the South), Martin and company amplified JFK’s support of the Democrats’ strong civil rights plank in a series of brilliant advertisements. The campaigns included a Martin favorite, “A Leader in the Tradition of Roosevelt,” as well as a set of side-by-side pictures of JFK and famous black heroes, from Rep. William Dawson of Chicago (his support was vital) to Virginia Battle, the African-American secretary Kennedy had recruited to his Senate campaign in 1952.

In other words, Bryant’s work suggests: Long before the assassination of JFK catapulted him into the pantheon of civil rights leaders, Louis Martin et al. planted the idea in black newspapermen’s minds.

Along the way, Louis Martin (with others) had a hand in persuading candidate Kennedy to place a timely call to Coretta Scott King when her husband Martin was in jail and got New York’s black powerbroker, Rep. Adam Clayton Powell of Harlem, to accept $50,000 in exchange for making pro-Kennedy speeches. The call to Mrs. King was “ ‘the icing on the cake,’ ” Bryant quotes Louis Martin as saying. “‘But the cake was already made.’”

And when it came out of the oven …

Kennedy, in a tight election, won 78 percent of the black vote. Soon after, Martin became deputy chairman of the Democratic National Committee; but really, Bryant writes, Martin was, with his “great savvy in public relations,” Kennedy’s “personal point man on civil rights” (the stage manager of the black Camelot, if you will).

On the eve of the inauguration in Jan. 1961, Martin, with Kennedy’s other point man on civil rights, Harris Wofford (chairman of the subcabinet group on civil rights), lobbied the president-elect to at least include a nod to “human rights … at home and around the world” in the sterling speech Ted Sorenson more famously helped draft. All through the campaign, Kennedy had stressed that his approach to civil rights would flow from executive—more than legislative—action, and now, with Martin’s counsel in casting the players, he was ready to deliver.

The Black New Frontiersman

“ ‘I am not going to promise a Cabinet post to any race or ethnic group,’ ” JFK announced before the election, Bryant writes. “ ‘That is racism at its worse.’ ” Yet that is exactly what his “strategy of association” called for, except that the black men Kennedy hired were (to borrow from the late David Halberstam) “the best and brightest,” finally being given their shot to shine like Jackie Robinson had in a different “major league” 13 years before. In Kennedy’s first six months in office, the New York Amsterdam News reminded readers after the assassination, the Kennedy White House appointed some 50 black men (and women) to executive branch jobs.

But Louis Martin had already pushed those talking points out over a year before to Democratic party field workers (conveniently, those same talking points found their way to the Chicago Defender on April 21, 1962). In them, Martin emphasized the ceilings JFK had helped black professionals shatter in the federal government. He also reminded them that, unlike previous presidents, the positions Kennedy offered weren’t merely “advisory,” but were, as the headline ran, for “Negro Decision-Makers.” Their names, though largely forgotten to us now, were illustrious and continued being added to the rolls throughout JFK’s 1,000 days.

A Few of the African Americans in the Kennedy Administration

Andrew T. Hatcher, associate White House press secretary, the first black man to hold the No. 2 communications spot in the White House, behind his longtime political compatriot, Pierre Salinger. In fact, according to a profile in Ebony in October 1963, Hatcher pinch-hit for Salinger “200 days … as the official White House spokesmen at press briefings, on the mikes and on the job,” including during “the Mississippi Meredith case.” “The appointment was enough to jar ‘the old pros’ who had long become accustomed to Negroes serving only as porters, messengers, maids, clerks and valets at the White House,” Simeon Booker of Ebony wrote.

Dr. Robert Weaver, administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, “the highest appointive federal office ever held by an American Negro,” the Chicago Defender noted in its coverage of Weaver receiving the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal on June 5, 1962. (JFK tried to elevate Weaver to a full Cabinet member but was rebuffed by Southern Democrats around the same time he pushed to open up federal housing for blacks. Lyndon Baines Johnson, the legislator’s legislator, eventually made it happen, naming Weaver his first H.U.D. secretary in 1966.)

George L.P. Weaver, assistant aecretary of labor for Internal Affairs

Carl Rowan, deputy assistant secretary of state for Public Affairs (later LBJ’s director of the U.S. Information Agency, after Edward R. Murrow, and a nationally syndicated columnist)

Dr. Grace Hewell, program coordination officer, Department of Health, Education and Welfare

Christopher C. Scott, deputy assistant postmaster general for transportation

Lt. Commander Samuel Gravely, of the U.S.S. Falgout, the first black Navy commander to lead a combat ship, according to Martin

Dr. Mabel Murphy Smythe, member, U.S. Advisory Commission on Educational Exchange, Department of State

John P. Duncan, commissioner of the District of Columbia

Clifford Alexander Jr., national security council (later secretary of the army under President Carter)

A. Leon Higginbotham, a member of the five-man Federal Trade Commission, which, in September 1962, made him the first African American ever to be appointed to a federal regulatory agency—and only at age 35. (Higginbotham was a distinguished Philadelphia attorney who had graduated from Yale Law School and served as the city’s NAACP chapter president and former assistant district attorney; I was proud to recruit him and his wife Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham to teach at Harvard after I arrived in 1991.)

Plus:

The ambassadors: Carl Rowan, to Finland; Clifton Wharton, to Norway; and Mercer Cook, to Niger

U.S. attorneys: Cecil Poole, Northern California; and Merle McCurdy, Northern Ohio

President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity: Alice Dunnigan; John Hope; Azie Taylor (later, U.S. treasurer under President Carter); Hobart Taylor; John Wheeler; and Howard Woods.

Federal judges: James Benton Parsons, Northern District of Illinois, the first black federal district judge to serve inside the continental U.S.; Wade McCree, Eastern District of Michigan; Marjorie Lawson, Juvenile Court of the District of Columbia; and, “Mr. Civil Rights” himself (as Louis Martin referred to him), Thurgood Marshall, the Second Circuit, U.S. Court of Appeals. A. Leon Higginbotham would have made No. 5 when JFK nominated him for a district court judgeship in October 1963, but after the assassination, he was held over until LBJ submitted his name again in January 1964.

Read more of this blog post on The Root.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media