CHAPTER 1: THE EARLY AFRICAN DIASPORA:

A SCATTERING OF MILLIONS

FROM AFRICA TO THE AMERICAS

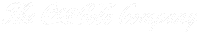

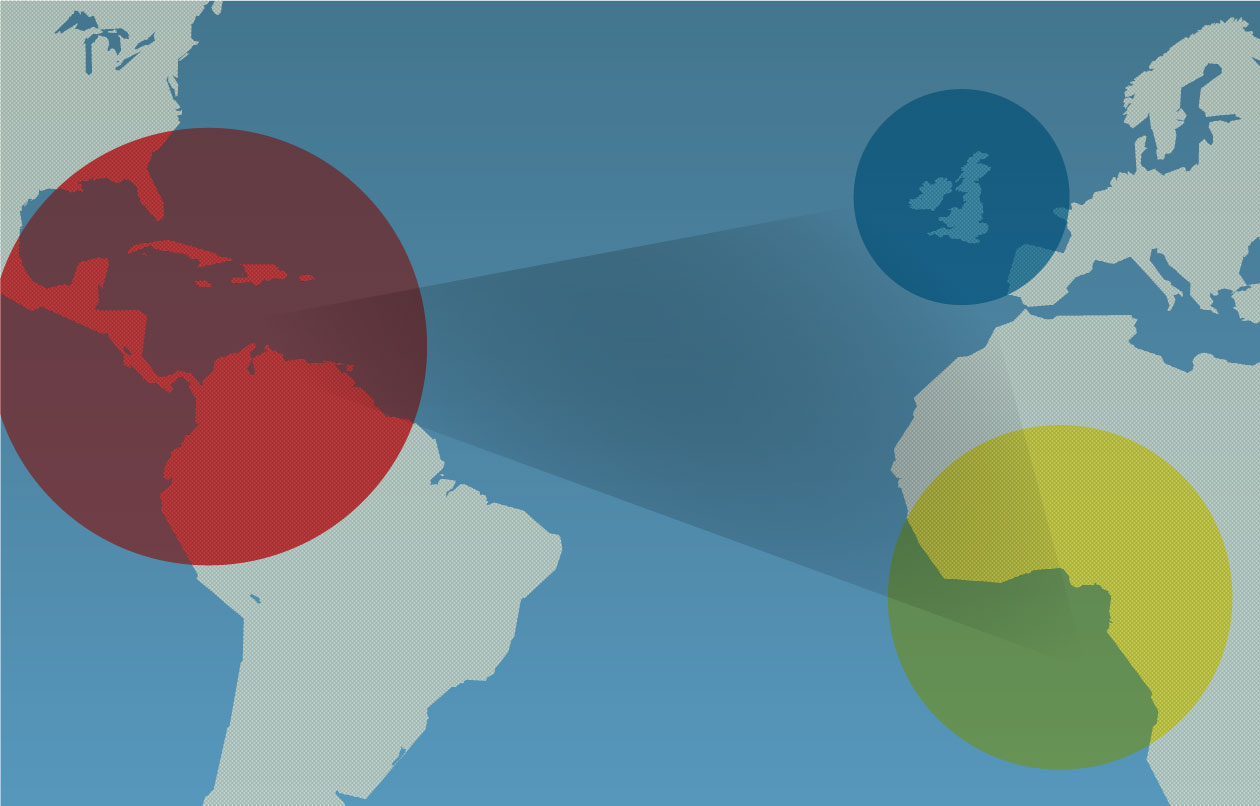

In the 360 years between 1500 and the end of the slave trade in the 1860s, at least 12 million Africans were forcibly taken to the Americas - then known as the "New World" to European settlers. This largest forced migration in human history relocated some 50 ethnic and linguistic groups.

Only a small portion of the enslaved - less than half a million - were sent to North America. The majority went to South America and the Caribbean. In the mid-1600s, Africans outnumbered Europeans in nascent cities such as Mexico City, Havana and Lima.

A TERRIBLE TRADE

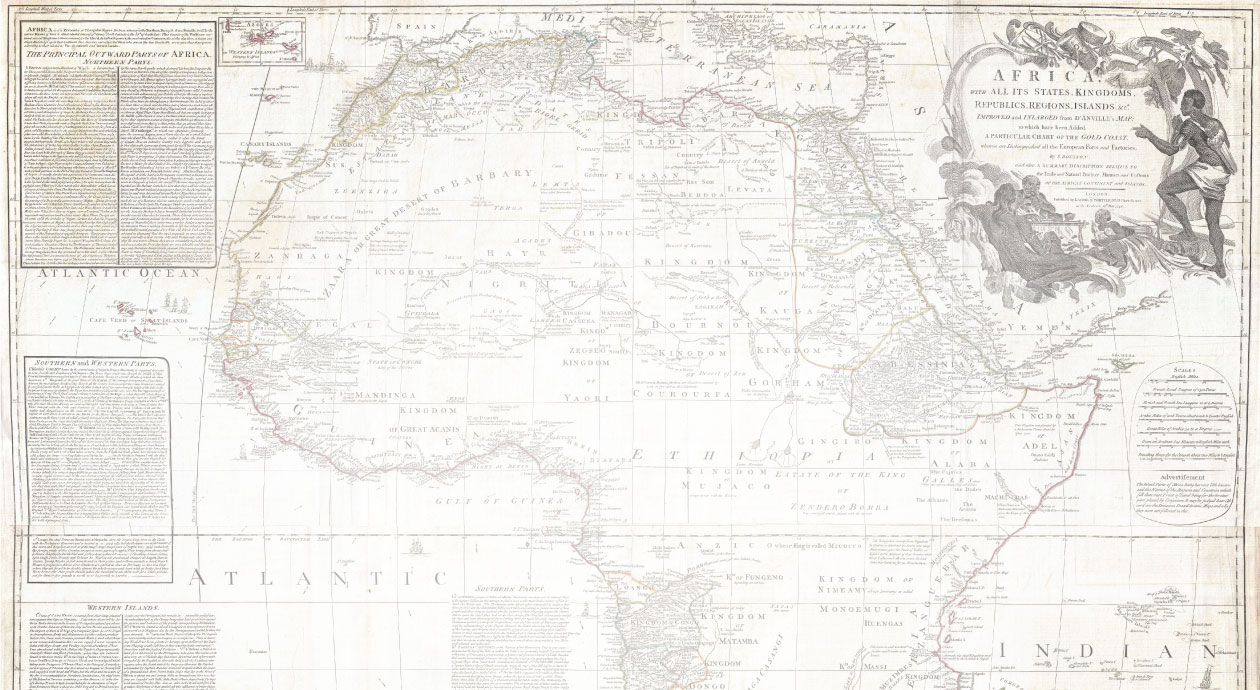

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade is called a Triangular Trade for its three-legged route that began and ended in Europe.

European vessels took goods to Africa, where they were exchanged for slaves. The ships then sailed to the Americas to trade slaves for agricultural products - extracted by slave labor - which were sold in Europe after the return journey.

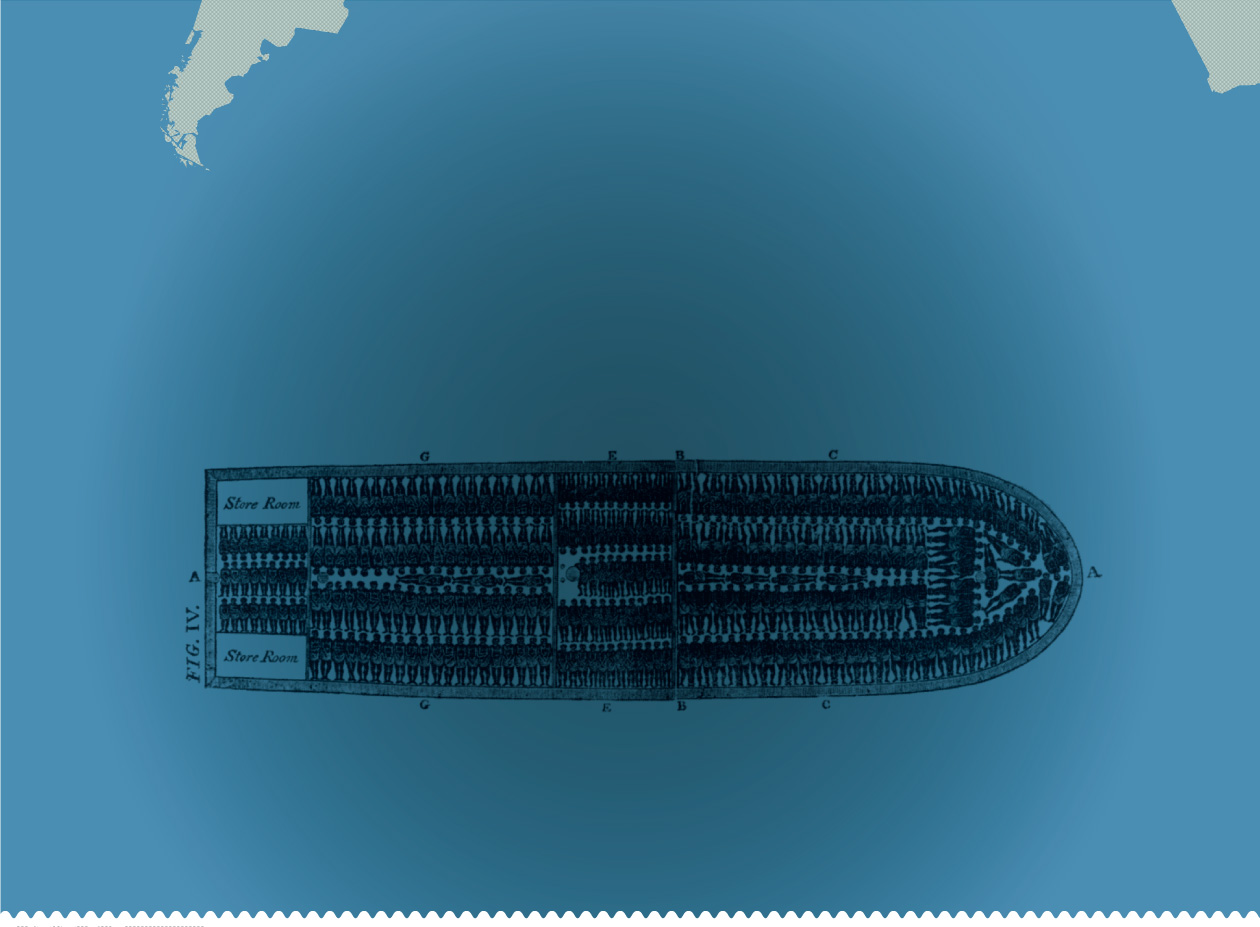

The Middle Passage

The journey between Africa and the Americas, "The Middle Passage," could take four to six weeks, but the average lasted between two and three months. Chained and crowded with no room to move, Africans were forced to make the journey under terrible conditions, naked and lying in filth.

The abhorrent conditions of captivity resulted in the deaths of an estimated 1.5 to 2 million men, women and children en route to the New World.

Nearly a quarter of the Africans brought to North America came from Angola, while an equal percentage, arriving later, originated in Senegambia.

Over 40 percent of Africans entered the U.S. through the port city of Charleston, South Carolina, the center of the U.S. slave trade.

CHAPTER 2:

THE FIRST GENERATIONS IN AMERICA

ENSLAVEMENT ACROSS THE ATLANTIC

The earliest slaves in North America worked on plantations along the southern coast, cultivating cash crops like rice and tobacco.

Freedom in Spanish Florida

The part of Florida held by the Spanish, south of St. Mary's River, became a destination for escaped slaves. To antagonize the British both militarily and economically, Spain welcomed slaves from the British territory, declared them free and set up the first free, all black settlement, Fort Mose, north of St. Augustine in 1738.

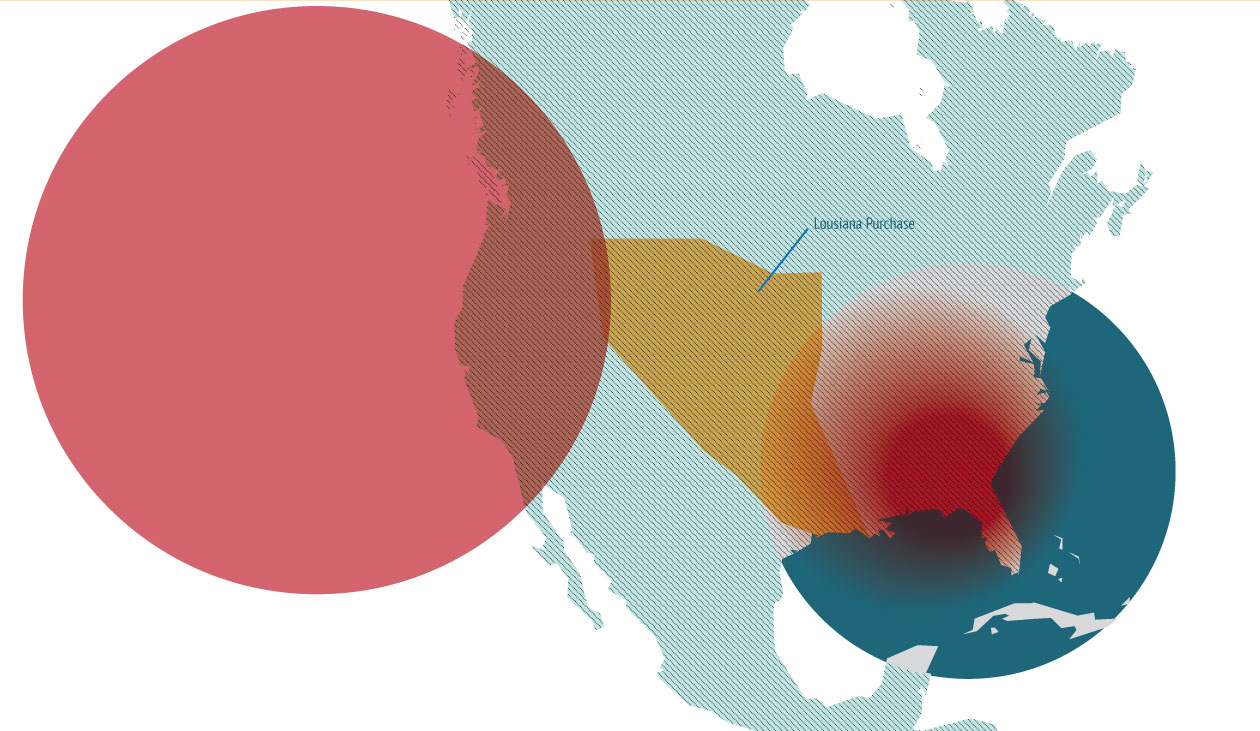

Successful escapes were rare. As the country expanded westward with acquisitions such as the 1803 Louisiana Purchase and inventions made cultivating certain crops more profitable, the demand for slave labor increased

A New Cash Crop

Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793 ushered in the new cotton economy. This new machine vastly multiplied the profit potential for America's planters, making it possible to separate seeds from cotton without destroying the fiber.

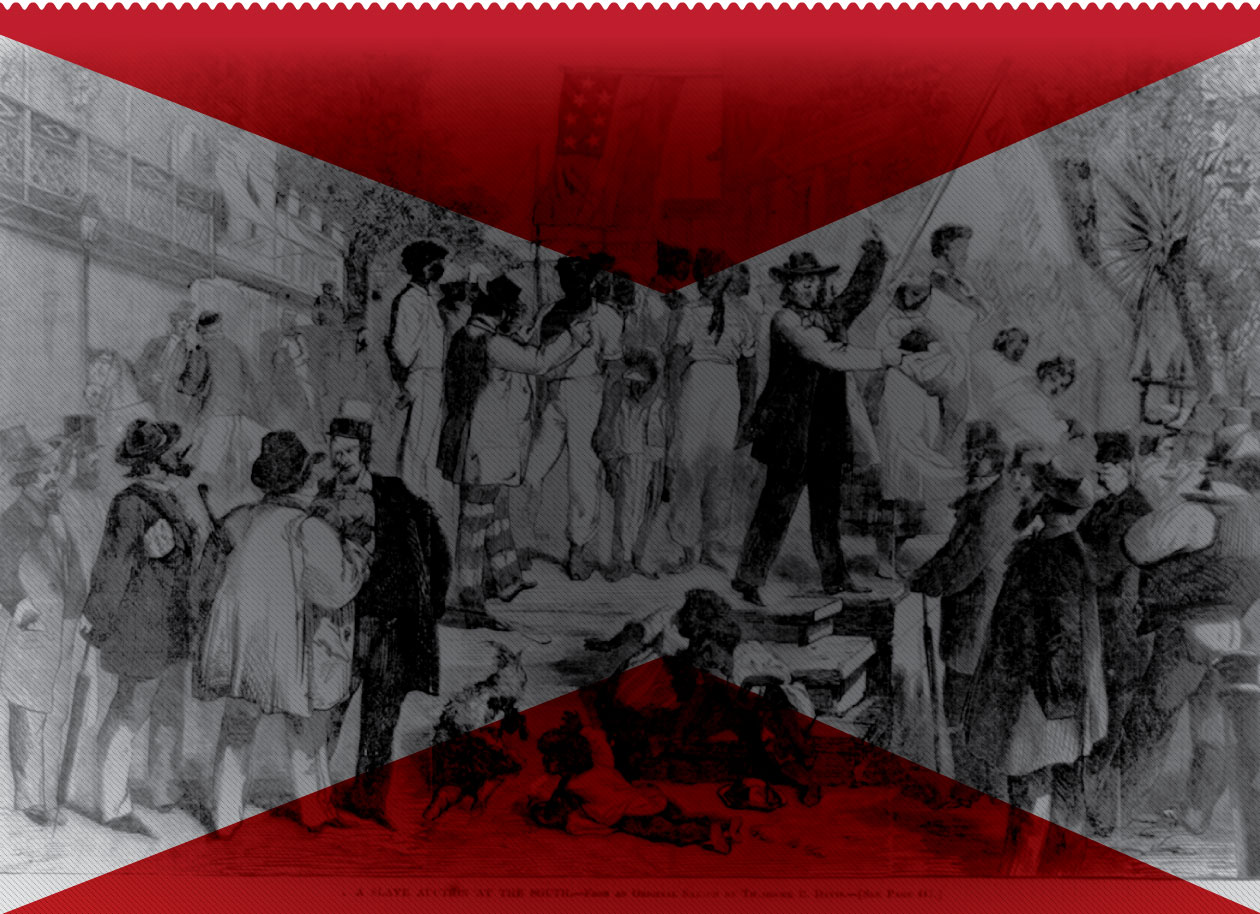

Cotton Fuels a Second Middle Passage

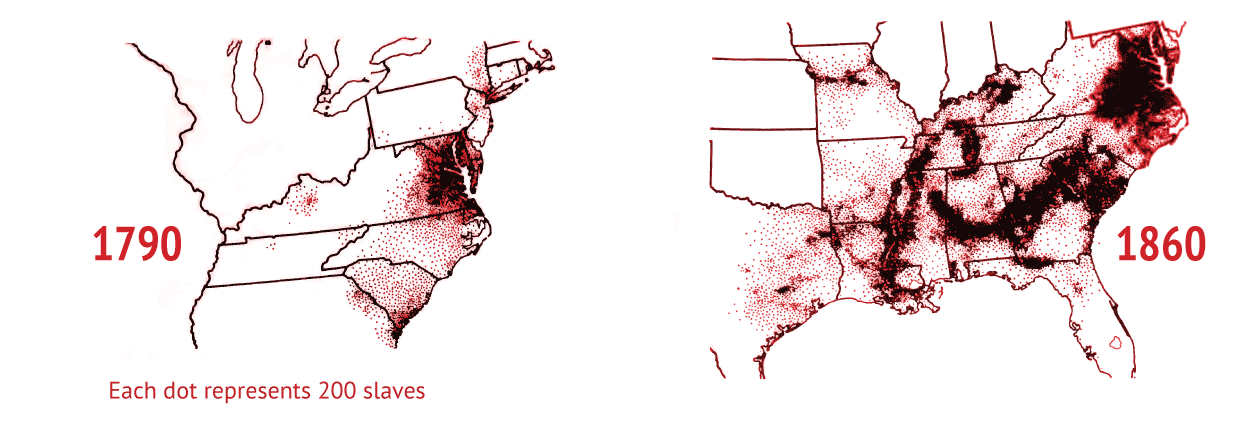

Cotton plantations spread in the "Deep South." According to the Federal census, in 1790 approximately 650,000 slaves worked with rice, tobacco, and indigo. By 1850 the country had 3.2 million slaves, 1.8 million of whom worked in cotton.

By the middle of the 19th century, the southern states were providing two-thirds of the world's supply of cotton.

Forced migration

and the separation of families happened within America, just as it did between Africa and the New World. The burgeoning agricultural economy not only created an enormous new region for slavery in the Lower South, it turned the Upper South into slave-exporting states, where families and individuals were at constant risk of being sold away from whatever stable base they had. Families that had been intact for generations along the Atlantic coast were forever separated.

CHAPTER 3: ESCAPED AND FREE BLACKS

RUNAWAY JOURNEYS

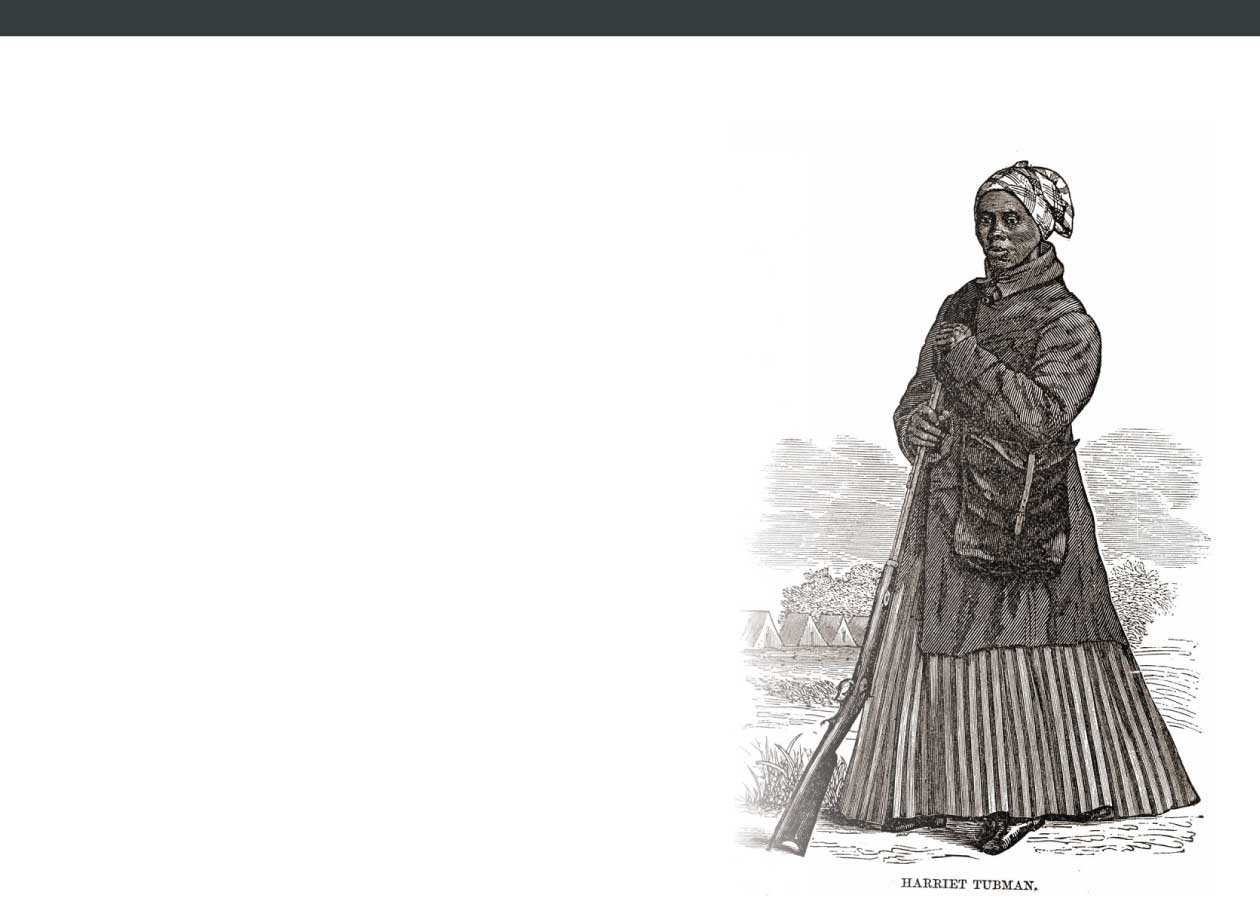

Since the earliest days of slavery, African Americans risked everything to find freedom. Escaped slaves made their way to Canada, Mexico and areas of the United States where they could live free.

Not run by any one person or organization, the Underground Railroad was a large network of safe houses and routes that escaped slaves used to travel to the North, often covering 10 to 20 miles each day. Harriet Tubman, who escaped from slavery in 1849, is famous for her work as one of the many "conductors" on the Underground Railroad. She journeyed often into the South to help slaves find their way.

FREE IN THE NORTH AND SOUTH

Although Southern states made life for a free black difficult, whether denying residency or threatening re-enslavement for minor criminal offenses, more free blacks lived there than in Northern states, even through the Civil War.

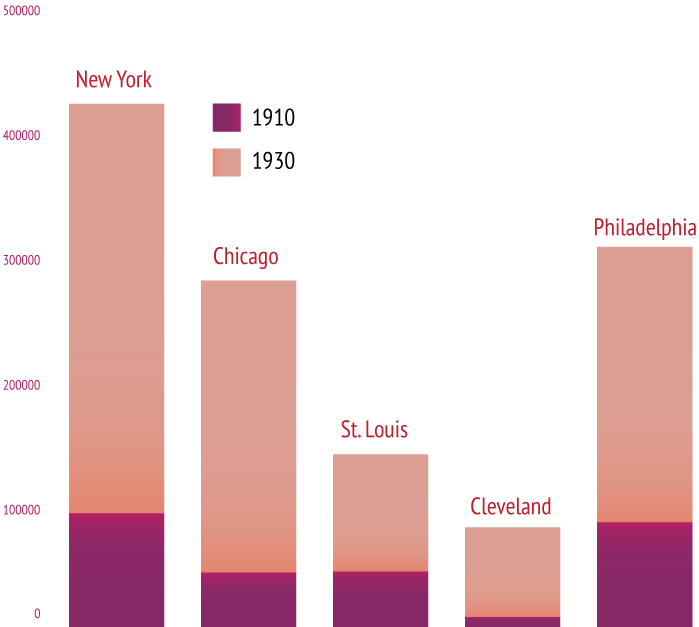

When slavery was abolished at the end of the Civil War in 1865, the greatest increases in the black population of northern cities were in Cleveland, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

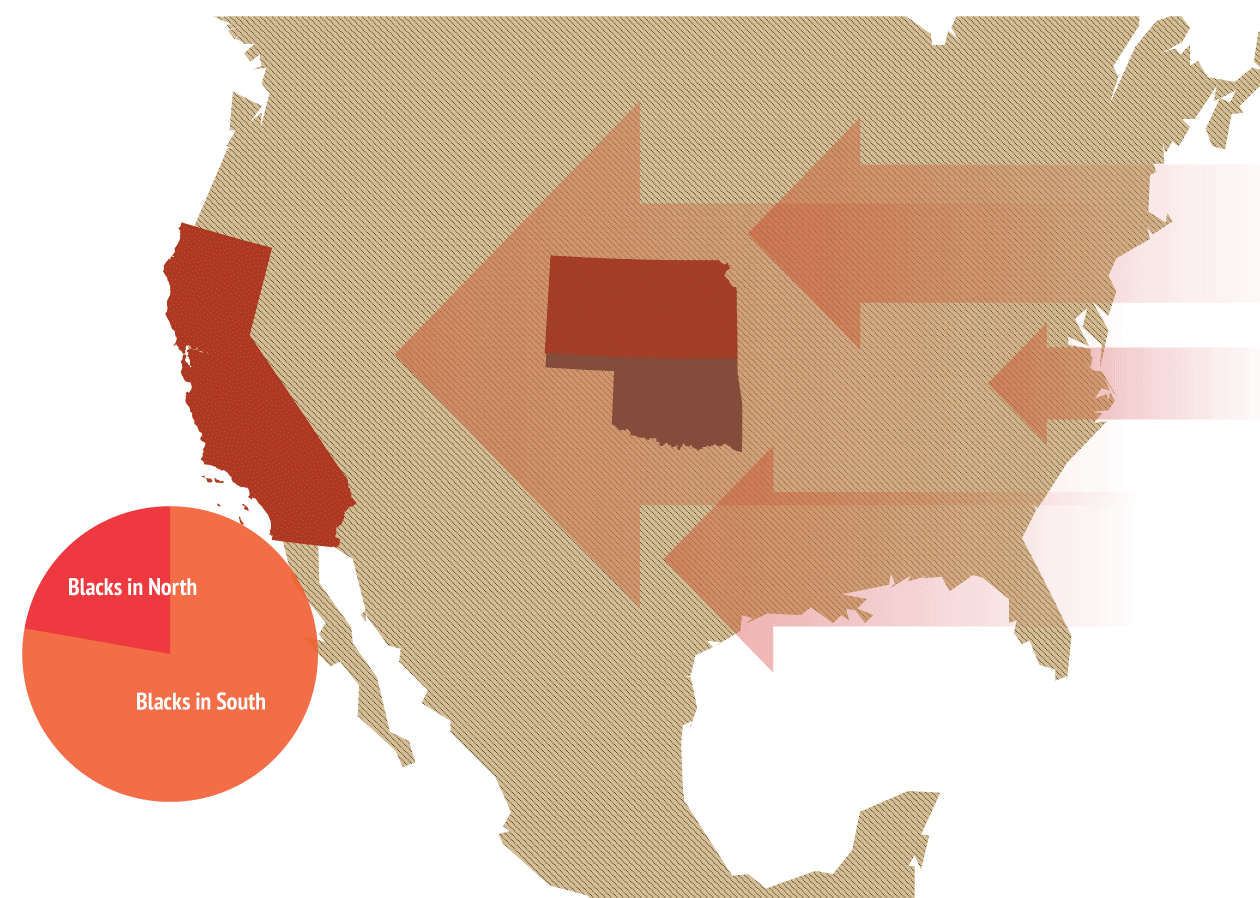

In 1860, free blacks numbered 488,070, about 10 percent of the entire black population. Of those, 226,152 lived in the North and 261,918 in the South.

Early Westward Migration

Between 1850 and 1860, 4,000 blacks settled in California. Half chose San Francisco and Sacramento, creating the first English-speaking, black urban communities in the far West.

The closest western state to the Old South that allowed blacks to homestead in the 1870s was Kansas. Between 1870 and 1890, some 30,000 blacks settled there.

In Oklahoma, by 1900 African American farmers owned 1.5 million acres, the peak of black land ownership there, which began to decline by 1910.

The first African Americans in California had arrived much earlier, from Mexico. In 1781, African Americans comprised a majority of the 44 founders of Los Angeles. They were joined by more blacks from Mexico when slavery ended there in 1821.

Though blacks made significant moves north and west, at the turn of the 20th century, over seven million of the nation's almost nine million blacks lived in the South.

CHAPTER 4: THE GREAT MIGRATION

A MASS MOVEMENT NORTH

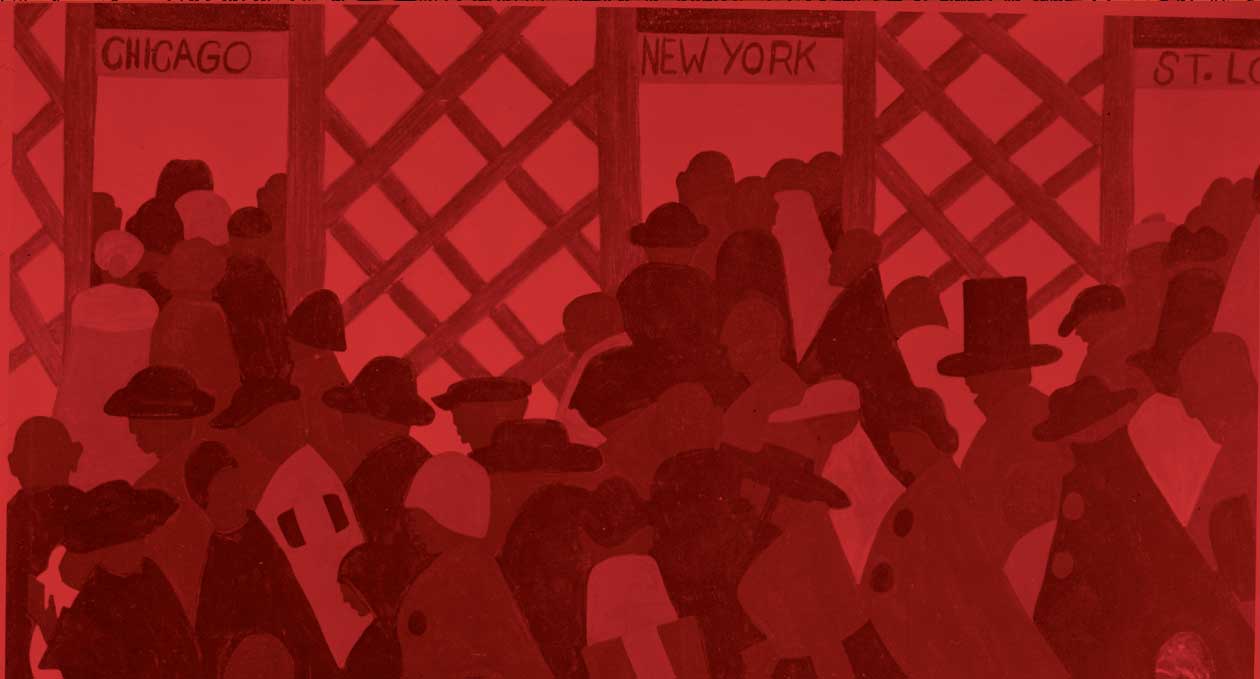

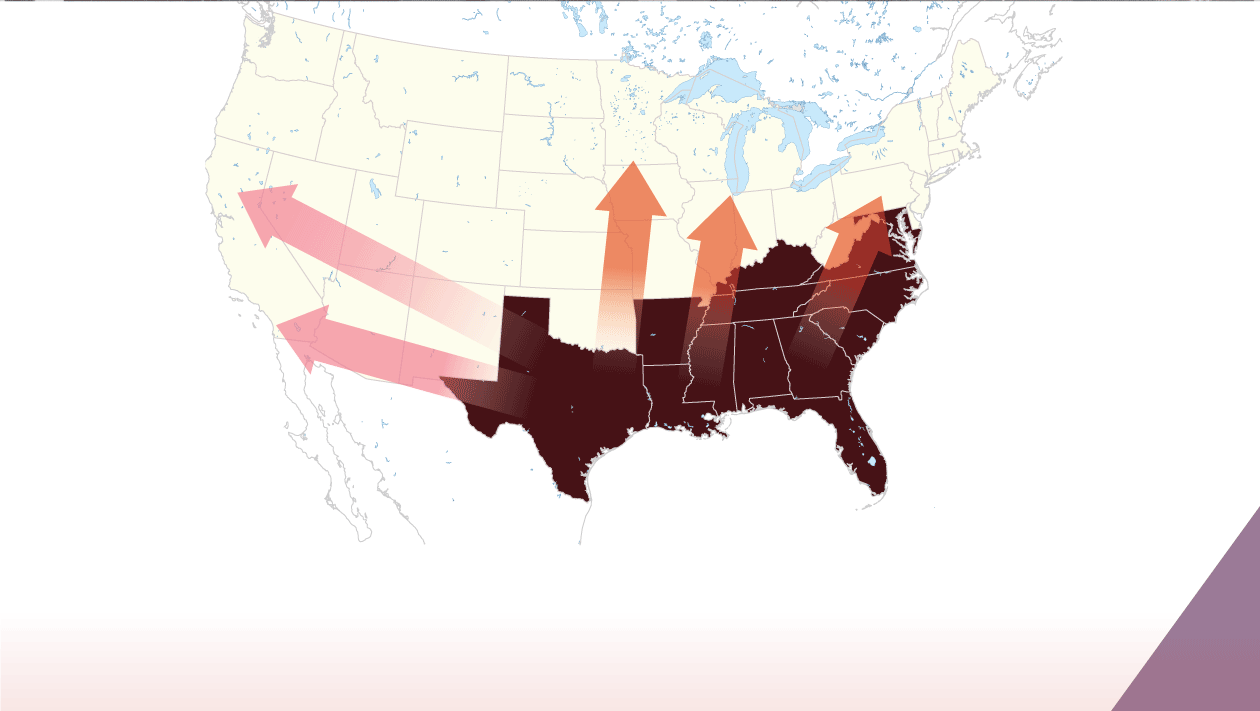

The Great Migration was one of the largest migrations ever of the African American population. Many scholars consider it as two waves, between 1916 and 1930, and from 1940 to 1970. The Great Migration saw a total of six million African Americans leave the South.

THE FIRST WAVE: OUT OF THE RURAL SOUTH

Work, both lack of it and opportunities, was a major reason for leaving the South. While the Boll Weevil infestation quickly destroyed the cotton industry between 1915 and 1920, World War I was creating jobs at factories and railroads in the North.

Between 1916 and 1918 alone, 400,000 African Americans migrated north. In the summer of 1916, the Pennsylvania Railroad helped more than 10,000 African Americans move in order to employ them.

A Population Shift

The growing population of African Americans in more northern urban areas created strong and distinct communities that supported everything from black-owned businesses, hospitals, and institutions to major cultural developments.

A Rising Culture

The wealth and community of talents in New York City helped spark The Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, when writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, artists Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, musicians Duke Ellington and James P. Johnson, and activists Marcus Garvey and A. Philip Randolph gained recognition and fame.

The Urban South

Blacks moved to southern metropolitan areas, too. In the 1920s, cities like Atlanta, Birmingham, Houston, and Memphis experienced black population growth rates ranging from 41 to 86 percent.

THE SECOND WAVE: OUT OF THE RURAL SOUTH

The stock market crash of 1929 and Great Depression that followed slowed the migration trend. However, as World War II revved up industry production, African Americans began to move from rural areas and into city centers again, and from southern cities to northern ones. By the end of World War II, the majority of the black population lived in urban areas.

HEADING TO THE WEST COAST

This second wave saw more migration to coastal cities of California, Oregon, and Washington. Oklahoma lost 23,300 African Americans, 14 percent of its black population, while the state of California gained 338,000.

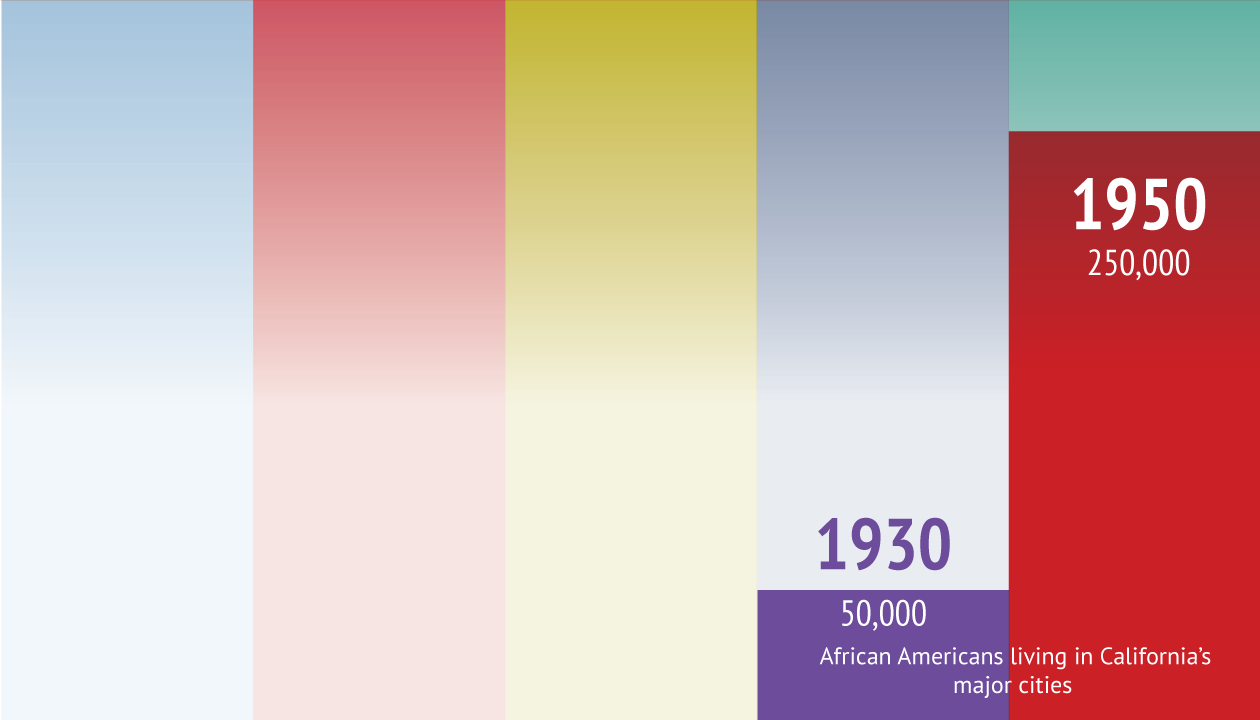

In 1930, there were slightly over 50,000 African Americans living in California's major cities. By 1950 that number had increased to over 250,000.

CHAPTER 5: THE NEW GREAT MIGRATION

A REVERSE MIGRATION

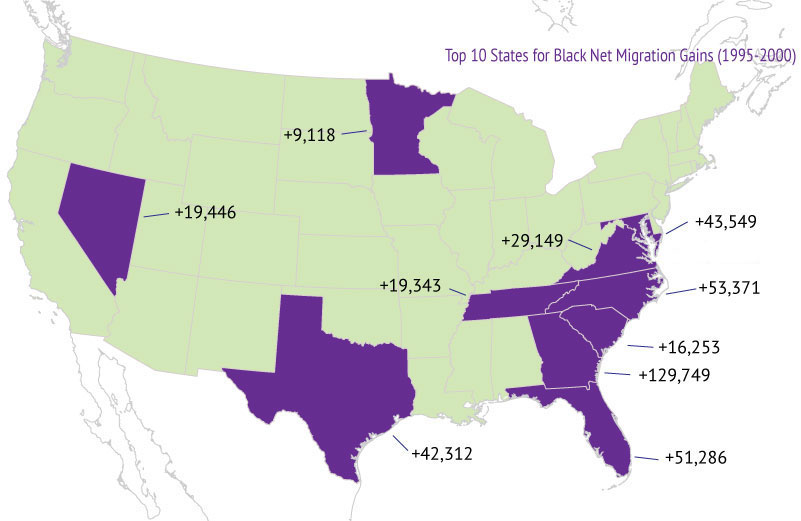

The last decades of the 20th century marked a new migration trend - by 1970 there were more African Americans heading to the South than leaving it. It was already in the late 1960s that the number of African Americans moving to the South eclipsed the number leaving. Since then, black migration to the South has continued to grow.

WHY MOVE SOUTH?

The two biggest reasons for this trend have been familial ties and economic betterment. African Americans who have made this return - the vast majority of them have never lived in the South - have returned to areas where their families had been based. While northern cities have seen a decrease in manufacturing, industry and jobs are growing in the South and West. Cheap labor, tax breaks, and inexpensive land have generated more industrial jobs in the regions and have brought other economic opportunities with them. A lower cost of living has added reason to make the geographical move.

By 2010, Atlanta had surpassed Chicago as the metro area with the largest African-American population after New York.

A significant new migration movement is that of immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean. Between 2000 and 2010, black Africans represented the fastest-growing segment of the country's foreign-born population. In 2011, 1.7 million immigrants from the Caribbean and about 1.1 million from Africa were living in the country.

Less than 10% of Caribbean blacks live outside the Northeast and Florida. African immigrants are more widely settled. They are mostly concentrated in New York, Texas, California, Florida, and Illinois, with 21% living in Midwestern states, and 15% in Western states.

The African-American journey begins again.

PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.