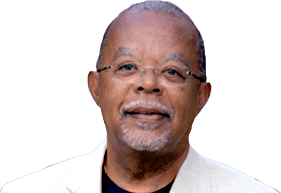

Should Blacks Collect Racist Memorabilia?

I have a confession to make: I collect racist memorabilia. Perhaps it is because my mother seems to have as well. She kept a very small ashtray on a table in our living room featuring a Black Sambo figurine at its center. Since neither of our parents ever smoked, I know Mom didn’t buy this object for its function; she bought it because she was intrigued, just as I was, even as a child. Why was this boy so very black — jet black, the blackest of blacks — and why was he depicted as naked? Again and again in idle moments, I would be drawn to the plight of this little black boy, frozen for all time in a racist form of in extremis, I guess one might say, with the reddest and thickest of lips, the whitest of eyes and the unutterably blackest of skin.

When it comes to the question of whether collecting those racist images is right, I often encounter two strong and diametrically opposed reactions from African Americans. Some can’t seem to amass enough examples of these “collectibles” or “memorabilia” (as we euphemistically call these hideous images today). Others think the whole lot should be assembled into one gigantic bonfire, incinerated, and the ashes buried in an impenetrable vault, or strewn over the broadest reach of the deepest ocean never to be displayed again. It’s as if these artifacts’ complete and total obliteration could wipe the slate clean or erase the painful memory and palpably harmful effects of seeing ourselves reflected over and over through the murky mirror of the anti-black subconscious as deracinated, gluttonous, lascivious non-reflective sub-human beasts — thieves, rapists, liars — a species apart from all other human beings, dominated and ruled like other animals by our instincts and passions and not by our (sub-standard) brains.

I understand the latter reaction, so it may seem counterintuitive that I pursue a scholarly interest in what I think of as the everyday racism of the genre of American popular culture that I call “Sambo Art.” In fact, one of the components of Harvard’s extensive “Image of the Black in Western Art Archive” — composed of some 26,000 images of black people in Western art, both noble and ignoble, in both high and low art forms — is made up of these racist images, which I hope scholars will study, analyze and critique: first, to understand why and how they came into being and were used to demean and delimit our people as human beings and as citizens, and second, so that we can keep this sort of thing from being used against our people and any other subjugated people ever again, to paraphrase the defiant assertion of many Jewish people in relation to the Holocaust.

I thought about all of this a few days ago, when I walked into the Sable Images Shop near Leimert Park, bordering the Baldwin Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, while filming an episode of “The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross,” our six-hour African-American history series to be aired on PBS starting on Oct. 22. The lovely shop, owned and operated by an African-American woman, Gail Deculus-Johnson, is chock-full of historical examples of Sambo Art, ranging from 19th-century minstrel imagery all the way to advertisements for the Amos ‘n’ Andy television program in the early 1950s. What makes this shop different from others I have visited is a very thoughtful pamphlet that Deculus-Johnson distributes to her customers, in which she discusses why she collects and sells these items.

In response to this fascinating rhetorical question — “[Since] some items are disturbing, offensive and hard to believe, [if you collect and display them] are you creating these images yourself?” — her pamphlet answers: “No, definitely not,” since the store “contains astounding mementos reflecting true lives of people of African descent,” including all that African Americans have suffered through visual media, “depictions [that] are a testimony of life in the past,” including “the ‘good, bad, and ugly.’ ” And in response to whether “these politically incorrect depictions” are, in fact, “teaching racism,” the pamphlet answers that “displaying memorabilia as part of a home, no matter how painful it may seem, is ensuring that ‘each one teach one’ and that history must not repeat itself.” Our children, it continues, “must know where we have been to know where we are going.” In other words, the most important function of displaying and collecting this stuff is a didactic one: critique. And there is a lot here to critique.

The first question that strikes any student of Sambo Art is, Why so many images? It is the sheer number of these images that strikes me as perhaps the most amazing fact about them collectively. I mean, how many ways can one call a woman or a man “nigger” or “coon”? How many watermelons does a person have to be represented as devouring, how many chickens stolen, to make the point that black people are ostensibly by nature gluttonous thieves? Why in the world did anyone think it necessary to produce tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of discrete racist images — a set of fixed types or motifs, including those luscious watermelons and irresistible plump chickens, ranging across virtually every conceivable form of American popular culture following the end of Reconstruction and more particularly at the turn of the 19th century? The explanation comes in three words: justifying Jim Crow.

The Reconstruction period between 1865 and 1877, immediately following the abolition of slavery with the ratification of the 13th Amendment at the close of the Civil War, affirmed that African Americans were inherently equal to white Americans and any other human beings, capable of voting, serving as jurors, testifying in court, buying and cultivating land, forming stable social and cultural institutions, marrying, having families, raising children, learning to read and write — in short, capable of mastering and exemplifying all of the hallmarks of citizenship that make this republic great. Despite centuries of anti-black racist discourse, it turned out that in 12 short years, the mass of the African-American people (90 percent of whom were still in bondage in 1860, a year before the Civil War broke out) demonstrated that they were human beings just like everybody else.

As W.E.B. Du Bois put it, “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.” How was the genie of freedom and equality forced back into the bottle of segregation and second-class citizenship? How was it that the emancipated were “moved back again toward slavery” after only a few years “in the sun”?

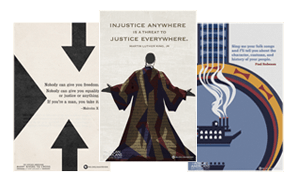

It turns out the assault was double-barreled: first through a series of Jim Crow laws and court rulings that effectively reversed or neutralized the Civil Rights Act of 1875 and the 14th and 15th Amendments (guaranteeing equal protection under the law and outlawing race-based voting discrimination, respectively), and second (and almost simultaneously) through the astonishingly wide distribution of a massive mountain of negative Sambo images, which were intended to naturalize the image of the black person as sub-human and in doing so justify and subliminally reinforce the perverted logic of the separate and unequal system of Jim Crow itself. The assault was devastatingly effective and brilliantly evil. While next week’s column will delve into the legal history with a focus on the era’s most notorious case, let’s touch on it first and then take a look at some of these horrific images.

We can say that the legal history of what the historian C. Vann Woodward titled his book, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, took shape in 1883, when the Supreme Court (in United States v. Harris, 106 U.S. 629) emboldened militant groups like the Ku Klux Klan by striking down a congressional law (the so-called Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871) that attempted to force states to prosecute individuals for conspiring to suppress black people’s 14th Amendment rights, even when, in the particular case before the justices, it involved an armed mob dragging four black prisoners out of a Tennessee jail.

From there forward, a series of laws and legal decisions continued to chip away at these rights. The naked racist underpinnings of these decisions are laid bare in comments about the “nature” of negroes declared in the Mississippi Supreme Court opinion that Justice Joseph McKenna subsequently quoted in his majority opinion for the U.S. Supreme Court in Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213 (1898), ruling that discrimination must be found in the text of a state’s laws, not just in their administration: “By reason of its previous condition of servitude and dependencies, this race has acquired or accentuated certain peculiarities of habit, of temperament, and of character, which clearly distinguished it as a race from the whites. A patient, docile people; but careless, landless, migratory within narrow limits, without forethought; and its criminal members given to furtive offences, rather than the robust crimes of whites.”

Sambo’s Role in the New Status Quo

The tone struck in the Williams v. Mississippi decision mirrored a trend in the American consumer market, which was inundated with the most debased images of black people. Following the Civil War, because of the technological innovation of chromolithography, it became cheap to mass-produce multicolored advertisements. By the 1890s — precisely when Jim Crow was hardening as the law of the land — one of the most popular forms of these advertisements was the widespread distribution of extremely demeaning and negative images of African Americans. So popular were they with the public, so widespread was their consumption, that virtually anywhere a white person saw an image of an African American they saw one of these stereotypes of a sub-human, deracinated beast-like being, like a visual mantra reinforcing the negativity of difference.

So, when a white person confronted an actual black human being, he or she was “an already read text,” to use Barbara Johnson’s brilliant definition of a stereotype in her book, A World of Difference. It didn’t matter what the individual black man or woman said and did, because negative images of them in the popular imagination already existed, as if they were “always ‘in place,’ ” as my colleague Homi K. Bhabha puts it (pdf), “already known, and something that must be anxiously repeated … as if the essential … bestial sexual license of the African [for example] that needs no proof, can never really, in discourse, be proved.” Hence the need to repeat these images over and over again, endlessly. The racist stereotype was subconsciously imposed on the face of an actual African American, the American mask of blackness, and these images justified the rollback of the gains black people had made during Reconstruction.

The fears and anxieties of black people from within the white collective unconscious were projected onto a plethora of quotidian, everyday, ordinary consumer objects, as we depict in the accompanying slide show, including post cards and trading cards, teapots and tea cozies, children’s banks and children’s games, napkin holders and pot holders, clocks and ash trays, sheet music and greeting cards, consumer products such as Aunt Jemima pancake mix and Gold Dust washing powder, Nigger Head tobacco and Jolly Nigger Head banks, “Pick the Pickaninny” songs, puzzles and dolls, Valentine Day cards, a seemingly endless number of watermelon-devouring and chicken-stealing “coons” and a veritable deluge of Sambo imagery spread throughout virtually every form of advertisement for a consumer product.

One motif illustrates the history of evolution by showing the transmutation of a watermelon into a “coon.” A sub-genre of lynching postcards also became popular, especially “The Dogwood Tree,” depicting five black bodies hanging from one tree in Sabine County, Texas on June 22, 1908 (see slide show below). One accompanying caption says: “In the Sunny South, the Land of the Free,/Let the WHITE SUPREME forever be./Let this a warning to all negroes be,/Or they’ll suffer the fate of the DOGWOOD TREE.” It’s no surprise that between 1889 and 1918, according to the NAACP’s “Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States,” more than 3,000 lynchings took place in the U.S., a reflection of the powerful effect these racist images had to justify otherwise decent people to commit the most horrific crimes.

Meanwhile, images of the black people as childlike even extended to those living in Cuba and Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War, as we can see in an 1899 illustration from Puck, included in the slide show below.

We should understand that this Sambo “art” is the way that anti-black racism found its daily existence, drowning out the actual nature and achievements of black people, and it explains why so many black thinkers and artists embarked upon “The New Negro” movement between 1900 and 1925, starting with Du Bois’ exhibition of photographs of middle-class Negroes at the Paris Exposition of 1900. As Du Bois put it in Darkwater, “One cannot ignore the extraordinary fact that a world campaign beginning with the slave-trade and ending with the refusal to capitalize the word ‘Negro,’ leading through a passionate defense of slavery by attributing every bestiality to blacks and finally culminating in the evident modern profit which lies in degrading blacks — all this has unconsciously trained millions of honest, modern men into the belief that black folk are sub-human,” “a mass of despicable men, inhuman; at best, laughable; at worst, the meat of mobs and fury.”

Chromolithography and the American marketplace made anti-black racism a commodity, widely consumed in the most unconscious ways, reinforcing and reflecting the legalization of racism and the delimitations being systematically inflicted upon the rights of black citizens by the courts and Southern legislatures. As the historian Thomas Holt concludes in “Marking: Race, Race-making, and the Writing of History” (pdf), a brilliant analysis of the role of minstrelsy in naturalizing every day anti-black racism, “it is precisely within the ordinary and everyday that racialization has been most effective, where it makes race,” a process “that fixes the meaning of one’s self before one even had had the opportunity to live and make a self,” “capable of communicating at a glance accumulated stores of racialized knowledge.”

To return to the question that Gail Deculus-Johnson poses in her brochure at Sable Images in Los Angeles — why should we collect these racist artifacts? — it would be good to turn to Du Bois for an answer. “In the fight against race prejudice,” he explained in Darkwater, “we were facing age-long complexes sunk low largely to unconscious habit and irrational urge.” And the shadow of these images still haunts every African-American’s existence within American society, like ghosts of the Jim Crow past, because “it is at this level that race is reproduced long after its original historical stimulus — the slave trade and slavery. It is at this level that seemingly rational and ordinary folk commit irrational and extraordinary acts,” as Thomas Holt writes.

In other words, these images are still very much with us, as one can see by examining the horrifically racist images of President Obama already collected at the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University, founded and curated by David Pilgrim. And we need to study these images in order to deflect the harm that they continue to inflict upon African Americans, at the deepest levels of the American unconscious.

This Friday, June 7, marks the 121st anniversary of a more immediate harm inflicted on a 30-year-old Creole man whose name would become associated with one of the most notorious cases in U.S. Supreme Court history. The reason he was jailed: sitting on a “Whites Only” car on a Louisiana railroad. His intention: deliberate. Even though he could pass for white, he announced he was black. In testing his state’s Jim Crow law, he and the legal team behind him defied stereotypes. The legal opinions that followed reinforced them. Remember Homer Plessy this Friday and read about his case and other “Strange Faces of Jim Crow” here in next week’s column.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media