The Black Governor Who Was Almost a Senator

Why didn’t more than one black person serve in the Senate during the Reconstruction era — a condition that persisted until this year, when Sen. Tim Scott served, first with William “Mo” Cowan, and now with Cory Booker?

We know, from the vantage of history, that Reconstruction in the United States lasted little more than a decade, from the dawn of emancipation at the midpoint of the Civil War until the politically expedient withdrawal of federal troops from the conquered former Confederate States of America in 1877. Yet it is important to remember that no one who lived through those fitful years of promise, experimentation and gathering clouds knew how it would turn out, or when. And with former slaves and free blacks being a fledgling but still strong voting presence in the deepest parts of the South, Mississippi sent its second black U.S. senator-elect to Washington in 1875. It was four years after the first, Hiram Revels (whom we met last week), left office. Already waiting there — but still unsworn after two years — was the first black senator Louisiana had sent forth: the state’s former acting governor, P.B.S. Pinchback.

Throughout Reconstruction, white Northern carpetbaggers vied with Southern scalawags for the elephant’s share of Republican Party spoils, but the most ambitious black men in the country were also determined to cash in. The two who almost joined each other in the Senate on March 5, 1875, were no exception. This is their story and that of the glass ceiling (actually a cast-iron dome) they would have smashed by serving together 138 years before Tim Scott (R-S.C.) and William “Mo” Cowan (D-Mass.) pulled off the feat this year, followed by Cory Booker (D-N.J.).

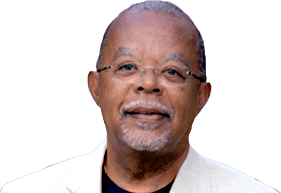

Blanche K. Bruce (R-Miss., 1875-1881)

The first was Blanche Kelso Bruce, a 34-year-old former slave born in Virginia to a black enslaved mother and a white plantation owner. Educated alongside the master’s son, Bruce left home (which by then was Missouri) when the Civil War began and his former study-mate joined the Confederate Army. At the midpoint of the war, Bruce narrowly escaped Quantrill’s Raiders, who, in the course of terrorizing Lawrence, Kansas in August 1863, “shot and hung over 150 defenseless people, as well as every black military man … stationed” there, writes Bruce biographer Lawrence Otis Graham, in his 2006 book, The Senator and the Socialite: The True Story of America’s First Black Dynasty. Fleeing for safety in Missouri, Bruce eventually opened the state’s first black school in Hannibal. After a year of study at Oberlin College, he worked as a steamship porter in St. Louis before catching wind of the opportunities Reconstruction was about to bring black men with prospects willing to relocate to black-majority states in the Deep South.

Bruce soon established his base of power in Bolivar County, Miss., Graham writes. At one time he served in three roles simultaneously: as tax assessor, sheriff and county superintendent of education. They were positions that earned him white men’s trust and, in the process, generated handsome fees in support of a lifestyle that included purchasing a white man’s sprawling cotton plantation. Bruce’s early sponsor in the Magnolia state was a former Confederate-brigadier-turned-Republican, James Alcorn, who would go on to become governor and U.S. senator. Despite the fact that Alcorn dangled promises of higher office, in the election of 1874 Bruce backed Alcorn’s rival for governor, Adelbert Ames, a Northern carpetbagger, who had offered Bruce something more specific: a ticket to the U.S. Senate. (No wonder Alcorn, then in the Senate himself, refused to escort Bruce to his swearing-in). White Republicans like Alcorn and Ames knew how to count votes, and in black-majority states like Mississippi, it was vital to cut deals with powerbrokers like Bruce who could deliver them.

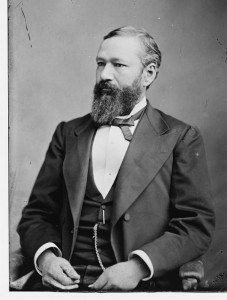

P.B.S. Pinchback (R-La.)

The other black man walking up the Capitol steps at the start of the 43rd Congress was Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback, a member of New Orleans’ black social elite. Like Bruce, Pinchback was the son of a white plantation owner and black slave mother, though apparently his father had emancipated his mother before she gave birth to him in Georgia in 1837. (Let’s just say Pinchback wasn’t their first.) Pinchback moved to Cincinnati with his brother, Napoleon, in 1847. By the time he was 12, he was supporting his family as a cabin boy after his father had died and the white side of the family left the black side penniless and in fear of being re-enslaved.

As a ship steward on the Mississippi, Pinchback learned the gambling arts from watching the more seasoned players onboard. With the hand he’d been dealt, he could’ve fooled most into thinking he was as white as any king in a deck of cards. Really, it wasn’t until the outbreak of the Civil War that Pinchback embraced being “a race man,” when, after a stint with the all-white First Louisiana Volunteers, he recruited black soldiers for the Corps d’Afrique and joined the Second Louisiana Native Guard (later, the 74th U.S. Colored Infantry). Once there, he eventually rose to captain before resigning over discriminatory promotional practices and unequal pay. After lobbying for black schools in Alabama, Pinchback returned to Louisiana in time for the state’s 1868 constitutional convention (a pre-condition for rejoining the Union). As a delegate, he “worked to create a state-supported public school system and wrote the provision guaranteeing racial equality in public transportation and licensed businesses,” as Carolyn Neumann writes in the Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619-1895.

Pinchback was serving as president pro tem of the Louisiana senate when, in 1871, the state’s first black lieutenant governor, Oliver Dunn, died. This left Pinchback to take his place. So far, timing seemed to be Pinchback’s strong suit, and it was again a year later when his nemesis, Louisiana’s white governor, Henry C. Warmouth, was impeached after a bitter election (more on that in a bit). In the fallout, Pinchback stepped in as acting governor from Dec. 9, 1872, to Jan. 13, 1873. It was just a blink of an eye, but as W.E.B. Du Bois noted in his towering 1935 study, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, Pinchback was the only black governor of any state during Reconstruction and remained the only one until Douglas Wilder’s election in Virginia in 1989.

“To all intents and purposes,” Du Bois wrote, Pinchback “was an educated, well-to-do, congenial white man, with but a few drops of Negro blood.” (If anything, he looked more like the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, a native of Scotland, than his famous black contemporary Frederick Douglass.) To Du Bois, it counted for a lot that Pinchback “did not stoop to deny” he had a black mother, “as so many of his fellow whites did.”

Pinchback’s grandson, Jean Toomer, one of the Harlem Renaissance’s most brilliant writers (you might know him as the author of the 1923 novel Cane), had a different take on his grandfather’s decision not to pass for white. “Did he believe he had some Negro blood? Did he not? I do not know,” Toomer (born Nathan Pinchback Toomer) wrote in his essay, “The Cane Years” (contained in the book The Wayward and the Seeking, edited by Darwin Turner). “What I do know is this — his belief or disbelief would have had no necessary relation to the facts.” Pinchback “claimed he had Negro blood, linked himself with the cause of the Negro and rose to power.”

That is, until he got to the Senate.

Pinchback might have assumed he was making the right (pragmatic) choice to back President Grant’s Republican slate in 1872, but when it came to verifying the returns, Pinchback’s old enemy, Gov. Warmouth (before his impeachment), insisted his preferred candidate, the Democrat John McEnery, had won. Warmouth used the machinery of government to try to make it so, even though when Reconstruction began, according to Du Bois, blacks in Louisiana accounted for 82,907 of the state’s 127,639 registered voters. For months — really, years — Louisiana was caught up in a bloody mess, as we saw most gruesomely in my column on theColfax Courthouse Massacre. There were even two inaugurations. “Practically,” Du Bois wrote, “so-called Reconstruction in Louisiana was a continuation of the Civil War.”

As a result, even though President Grant certified William Pitt Kellogg as the state’s duly elected governor, backing him up with military force, the U.S. Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections in Washington threw up a roadblock in front of the black man the Kellogg legislature chose to represent them. You guessed it: P.B.S. Pinchback. (Incidentally, he had also been elected to the U.S. House of Representatives but opted for the Senate.) If all had gone according to plan, Pinchback would have been sworn in March 4, 1873, two years before Blanche K. Bruce. Instead, as the opposition mounted, Pinchback soon found himself the poster child for an entire era of greed and corruption that Mark Twain famously coined “The Gilded Age.”

This is not to exonerate Pinchback, who, according to Eric Foner, in Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, as governor, had profited from a public land deal, speculated on insider information and otherwise fed off the patronage system. The point is that during “the Gilded Age,” senators in Washington suddenly seemed to get religion when it came to accepting this politician as one of their own. (To show just what a wheeler-and-dealer Pinchback was, in a posthumous article on Nov. 21, 1925, the Chicago Defender recalled how he was once asked, “Governor, how much do you think the delegates I told you about yesterday would sell out for?” To which “Pinchback, high-spirited, proud and unbending soul that he was, answered, ‘Senator, I cannot tell you that. I am used to buying votes, not selling them.’ “)

The Long Senate Debate

By the time Sen.-elect Bruce of Mississippi arrived for his swearing-in at the Capitol on March 5, 1875, Sen.-elect Pinchback of Louisiana had been awaiting his for two years, without satisfaction. Amazingly, the Civil Rights Act of 1875 had become law just four days before, and it affected all Americans by guaranteeing their right to “full and equal enjoyment of” public “accommodations,” “conveyances” and “other places of public amusement,” even “inns” and “theaters,” without regard to “race and color” or “previous condition of servitude.” Had Pinchback been sworn in on time, he might have been the one black senator to vote for it. (It did, however, receive seven black votes in the House — unfortunately not enough to prevent the law from being watered down through the sinking of its call for integrated schools.)

On swearing-in day, the New York Times reporter on the scene commented that “Mr. Bruce … a colored man of fine physique, intelligent features and gentlemanly bearing, next to [former President Andrew] Johnson commanded most attention from the galleries.” If anything, the Times reporter added, he “bears a striking resemblance to King Kalakaua,” the last king of Hawaii. (It was the heyday of color elitism in the U.S., and the paper of record had to find some way to signal to its readership that Bruce was less than white but a few steps up from black.)

As it turned out, what should have only been a ceremonial day in the Senate ended with an extra session to debate, among other things, what to do with the “other” black senator-elect in the wings. To indicate just how high the stakes were, the Chicago Tribune reporter on the scene noted that in addition to his supporters on the floor, “Pinchback himself sa[id] the Senate should not reject him now that a sure-enough nigger is seated [meaning Bruce].” His case was anything but under the noses of those in attendance, the Tribune made clear; for when Pinchback made his way into “the chamber at a side door, the whole gallery sent up a round of applause.” But this vote wasn’t about making history or garnering applause. When the extra session was over, Pinchback saw his potential Senate colleagues postpone his confirmation in a close 33-30 vote, curiously, with Blanche K. Bruce voting with the majority, perhaps because it seemed like the only available option to stave off an outright rejection on his first day as a Senate freshman.

Believe it or not, the curious case of P.B.S. Pinchback dragged on for another whole year in the Senate — three in all — until Sen. George Edmunds of Vermont, a fellow Republican, pushed through an amendment that inserted the word “no” in the pro-Pinchback resolution. On March 8, 1876, the full Senate approved it, 32 to 29. That five Republicans went along with the Democrats was a clear signal Reconstruction was losing steam, and as I said earlier, politicians always know how to count votes. With President Grant set to leave office after two terms in office, the Rutherford Hayes-Samuel Tilden election eight months later would be among the closest — and most controversial — in the nation’s history. This was until a deal was struck in the House to inaugurate the Republican Hayes in exchange for pulling federal troops out of the South — and with them hope for the recently emancipated slaves until the civil rights movement a century later.

Gov. Pinchback “represented the colored race; he was a representative colored man,” Sen. Alcorn of Mississippi argued just days after Sen. Bruce had joined him in the Mississippi delegation, according to the New York Times on March 17, 1875. But with the wheel quickly turning against such men, what had been almost a blessing at the start of Reconstruction was now a curse. Just before Pinchback went down in defeat, his friend Sen. Olivia Morton of Indiana, “intimat[ed] that if he had not been a colored man he would have been admitted long ago,” according to the New York Times on March 9, 1876. As Neumann writes, it was, Frederick Douglass lamented, “a mean and malignant prejudice of race.” “While the vote was being taken,” the Atlanta Constitution reported on March 9, 1876, “Mr. Pinchback was on the floor of the Senate and stood near the entrance at one of the cloak rooms. As the roll was called he manifested some nervousness, and, soon after the vote was announced, left the chamber.”

Read more of this blog post on The Root.

Fifty of the 100 Amazing Facts will be published on The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross website. Read all 100 Facts on The Root.

Find educational resources related to this program - and access to thousands of curriculum-targeted digital resources for the classroom at PBS LearningMedia.

Visit PBS Learning Media