Read Full Transcript EXPAND

|

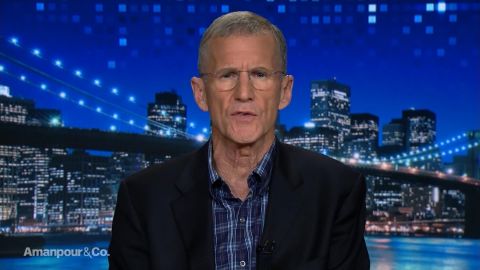

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up. A caravan of 7,000 migrants bears down on the United States through Mexico and President Trump is accused of manufacturing midterm hysteria. We get the latest on the ground, and we speak to the former Mexican Foreign Minister, Jorge Castaneda. Then, is American losing its longest war? I speak to Stanley McChrystal, former commander of Allied Troops in Afghanistan. And, our Walter Isaacson probes the origins of life, the universe and everything with Theoretical Physicist, Brian Greene. Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London. An estimated 7,500 migrants are heading north through Mexico fleeing violence and poverty in Guatemala and Honduras and hoping to reach the United States where they plan to seek asylum. Reporters on the ground say the migrant caravan consists of thousands of families including many mothers and children facing starvation and attacks on the long march north. Reporters and aid agencies see a full-blown humanitarian crisis developing. But President Trump lashed out in what a now familiar terms especially ahead of midterm elections. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) DONALD TRUMP, U.S. PRESIDENT: Going to the middle of the caravan, take your cameras and search. You’re going to find MS-13, you’re going to find Middle Eastern, you’re going to find everything. (END VIDEO CLIP) But a senior counterterrorism official contradicted Trump’s insinuation that terrorists have joined the caravan saying, “We do not see any evidence that ISIS or other Sunni terrorist groups are trying to infiltrate the southern U.S. border.” Correspondent Bill Weir has been following the caravan. He is joining me from Huixtla, Mexico. Bill, thank you for being with us. This is a gathering storm and a potential humanitarian crisis. What are you seeing on a day-to-day, step- by-step basis there? BILL WEIR, CNN CORRESPONDENT: Well, Christiane, just imagine if you or someone you know had taken everything you own and — that you could carry on your back and has walked hundreds and hundreds of kilometers, sometimes carrying your children, accepting food basically from the kindness of strangers like this man handing tortillas here and 13 days into the journey, you know, how would it feel? So, it is a day by day, minute by minute pursuit for survival. That’s what forced a lot of them initially to leave Honduras there and walk for the last 13 days. They have about a month or so, at least, before they reach the Western United States border as well. But I’m seeing mostly people — I’m seeing a lot of scenes like this where the kindness of Mexican strangers is helping feed and clothe these people as they make their way north as well. And of course, the idea there are hidden Muslim terrorists in this crowd is ludicrous on its face, you know, what the president could equally point out this group is 99.9 percent Christians, Catholics and Protestants alike and many of them fleeing both political and criminal violence in Honduras but the others fleeing poverty. And those who see the safety and numbers of this crowd moving north in Mexico, whether they are, or in Guatemala, they are deciding to join. It’s an opportunistic sort of thing, strength in numbers. And most are oblivious to the fact that the optics of this are playing out politically in the United States. They don’t have the luxury to think in those terms. But I’ve been asking people, first of all, do you know you’re breaking the law? And they acknowledge they are but say they have no other choice. And then I was reading the president’s tweets to some folks in the crowd yesterday, and here is one reaction. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) WEIR: He’s using the pictures of the big caravan saying it’s a mob of criminals, and there’s even Middle Eastern possible terrorists in there. UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): “I don’t understand why he’s saying that,” he says. “We’re not terrorists. Our country is very violent but the people are poor people.” WEIR: Do you have children? UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): That’s what hurts me the most, is I have three kids and I had to leave them behind because there’s no job. WEIR: When do you think you’ll see them again? UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): “I don’t know,” he says, “it’s up to God.” (END VIDEO CLIP) WEIR: Now, the caravan has halted here in this town about 80 kilometers north of the Mexico/Guatemala border, 50 miles or so, not out of fear of law enforcement or anything, other than to honor one of their own. One man from Honduras fell from an overloaded truck on the highway yesterday, fell to his death. The second confirmed death thus far. So, they paused to respect him and tell us they will head back forth before the crack of dawn tomorrow, Christiane. AMANPOUR: Yes. Bill, they do really do seem determined. I’m wondering why this is suddenly happening right now. We’ve seen periodically over the months and years that there are these long marches out of, as you describe it, poverty and violence and corruption at home. And what has triggered the latest one? And honestly, we’re seeing desperate pictures even on the Mexico/Guatemala border of people hurling themselves off bridges, trying to get on anything that floats to take them on to Mexican territory. WEIR: Yes. We were on the bridge when the Mexican Federales tried to stop the flow. Didn’t work very well. People jumped from the bridge, swam or rafted across there as well. The best I can gather is, really the initial spark of this caravan came out of the political climate that’s happening in Honduras. As the audience might recall, very contested election. Juan Orlando Hernandez, the president, was re-elected in what internal election watchers say was very suspicious terms. There was a week’s long recount. During that recount, President Trump congratulated him, promised him foreign aid as well. And then once in power, he’s taken on more of a strong man stance down there, appointing a lot of his cronies into the judgeships who then drop charges against people accused of embezzling massive amounts of that country’s wealth. They say 22 protesters were killed according to human rights watchers down there. So, that plus the cartel violence sparked the initial caravan to come out and then it just gathered steam, as people see this as an opportunity to find strength in numbers and comfort as they head north, as they support each other, people from different countries are now sort of this brotherhood of the caravan as they move north again, most of them oblivious to how it’s playing in the country of their destination. AMANPOUR: Bill, I’m really curious though to know they may be oblivious how it’s playing politically but they must have seen over the last months, you know, these awful scenes at the U.S.-Mexico border when families were separated. I mean, the last big crisis was that one. And I wonder, don’t they think that might happen to them? And you’ve been reporting that so many kids are on their way as well. WEIR: Yes, I’ve said again and again, “Do you understand what’s happening in the United States? Have you heard about family separations? Have you heard about President Trump’s threats to use soldiers to turn you away?” And all of their answers sort of harken back to an amazing poem by a Somali-English poet, Warsan Shire, who wrote, “You only leave home when home is the mouth of a shark. You only run for the border when you see your whole town running ahead of you. You only put your kid in a boat when you think the water is safer than the land.” They say, “We’ll take that choice, that uncertainty, that 5,000-kilometer hike up the length of Mexico with all the perils that go along with that.” They’ll choose that path rather than stay at home. AMANPOUR: I mean, it is extraordinary and the way you read that poem, it really does put it into sharp relief. Bill Weir, thank you so much. And now, to the Former Mexican Foreign Minister, Jorge Castaneda. He says if the people marching want to claim asylum in the United States, they should be allowed to cross through Mexico. And he’s joining me now, in fact, from New York. Mr. Castaneda, that is pretty provocative. You’re basically saying, “Hey, if you want to go to the United States, go through Mexico and you should be able to get to your destination.” JORGE CASTANEDA, FORMER MEXICAN FOREIGN MINISTER: Absolutely, Christiane. Good to be with you. It’s very important to understand that the United States has been pressuring Mexico for several months now for Mexico to agree to what President Trump said, that is that asylum should be requested in Mexico. But Mexico has not agreed to that and it shouldn’t agree to that. Some people want to request asylum in Mexico, about 1,000 have. Those requests will be processed. Some will be granted, others not. But other people don’t want to stop in Mexico, they want to go to the United States. Mexico should not be doing the United States’ dirty work for it. These people should be allowed to reach the border, ask — request asylum to American authorities at the border, and the United States will decide what it wants to do. There is no reason for all of them to be processed in Mexico, except that that’s what President Trump wants. AMANPOUR: OK. CASTANEDA: But that’s not a good enough reason. AMANPOUR: Well, what about, you know, I guess, the duty of care towards a lot of these migrants? I mean, you’ve seen with your very own eyes that those who get to the border, certainly over the last several months under this administration, have been, you know, detained, have had their children separated, this whole zero tolerance policy, which I admit has been, you know, retrenched under a lot of protests. But there are a huge number of kids who are still separated from their parents. I mean, why would any government encourage this caravan to keep moving? CASTANEDA: Well, it’s not a question of encouraging it, Christiane. They entered Mexico. The Mexico-Guatemalan border has been porous for 50 years at least. More than 50,000 refugees entered Mexico in the 1980s fleeing the war, the civil war in Guatemala. This is not a new story. People come and go every day across the river on these rubber rafts or swimming or whatever. So now, a group of Central Americans got together and instead of traveling alone and being much more vulnerable to rapists, assault, shakedown people, the Mexican authorities, which on occasion are very corrupt, they decided to band together, and in numbers there is safety. This is not for the Mexican government to decide what it should do with them. Can you imagine if we in Mexico were to put them in refugee camps and not allow them to leave? You remember the images in Hungary of the Syrians? AMANPOUR: Yes. CASTANEDA: Remember the images in Austria? We don’t want that either. So, why should we do the Americans’ dirty work? AMANPOUR: Well — CASTANEDA: Either they process these people in Honduras, which they could, or they process them on the U.S. side of the U.S.-Mexican border, not in Mexico. AMANPOUR: So, in a way, these people are political footballs wherever they are. They’re footballs on the U.S.-Mexico border. They’re footballs in their own country where they are fleeing, by all accounts, a huge amount of corruption, including under the latest elected president of Honduras. So, a couple of questions. In terms of the law, you say we don’t want to have, you know, refugee camps set up but the U.N. secretary-general is urging all parties to abide by international law, including the principle of “full respect for countries’ rights” to manage their own borders and the UNHCR, which is refugee agency, says that it’s deploying teams to ensure that travelers are fully informed regarding their rights to asylum along with providing legal advice and humanitarian assistance. I mean, they may very well have to end up putting up camps. CASTANEDA: Well, if — for those who want — who request asylum in Mexico, and, as I said, more than 1,000 have, and the Mexican government, apparently, is handling this in a humanitarian way after an initial mistake of tear gassing the women and children on the bridge across the Suchiate. Now, they’re doing this properly. UNHCR is helping, which is a good thing. And those who request asylum in Mexico should be kept in shelters while their requests are processed. Those who do not want to request asylum, we have two choices in Mexico. We deport them or we let them through. There is no way the Mexican government, the new one or the old one, can deport 7,000, 8,000, 9,000 people who are now only 100 miles from the border. I think the important thing here, Christiane, is to view this from a humanitarian point of view. These people are fleeing the violence in what is probably the most violent city in the world outside of countries at war, San Pedro Sula, in Northern Honduras, that’s what they’re fleeing from more than anything else. Whatever they run into in Mexico or in the United States is better than that. I can only congratulate Bill Weir for this excellent verse from the poet he mentioned about the shark. I mean, I think he got it just right. AMANPOUR: And, you know, mentioning Bill, he also said and reminded us that when this president was elected in Honduras, President Trump praised him and congratulated him and the administration promised a lot of aid. Now, President Trump is basically saying that — in fact, why don’t I just play what he said about the issue of aid. I’m going to play this soundbite. CASTANEDA: Sure. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) TRUMP: Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, they paid a lot of money. Every year we give them foreign aid and they did nothing for us, nothing. They did nothing for us. So, we give them tremendous amounts of money. You know what it is. You cover it all the time. Hundreds of millions of dollars. They, like a lot of others, do nothing for our country. (END VIDEO CLIP) AMANPOUR: So, he is threatening to take away that aid and, you know, using terms that you’re now familiar with. But does — what does that mean in the macro picture, threatening to take away aid? What will it do to this flow of caravan? CASTANEDA: Well, first of all, Christiane, it’s very little money. It’s what’s left of Vice President Biden initiative called Alliance for Prosperity for the three countries, actually the five countries in Central America which have been gradually reduced over the first two years of the Trump administration. There’s not a whole lot left. It’s not that much money. For you and me it is. But for big countries or relatively big countries, Guatemala has a population of 18 million people, it’s not that much money, firstly. Secondly, to cut it off is complete counterproductive. The money was sent there in the first place by the Obama administration initially to help people stay in Honduras and Guatemala and El Salvador, help people be more secure, help people against gangs, again the kidnappings, against the extortion, against the violence. You take that money away, all Trump is going to do is encourage more caravans, which are, by the way, are said to be already leaving Honduras and El Salvador as we speak. And it’s logical. Why is it happening now? I know you asked Bill Weir, Christiane, and I think it’s worth adding to what he said, which was quite right on the — was quite right. This has been — the numbers have been increasing for the past three months. September was the month of the greatest number of Central American families together reaching the U.S. border. It’s not that all of a sudden a lot more people are coming, it’s that a lot more people are coming together because it makes much more sense for them to protect themselves and also, to make it more difficult for Mexican authorities either to shake them down. We have corrupt authorities in Mexico, Christiane. You and I have spoken about these many times. That it’s senseless to deny it. Well, these people are protecting themselves from that and they are also placing the Mexican government in a very difficult situation, we have to agree to that. Trump is pressuring them on the one hand. You stop them. And public opinion in Mexico, Bill again has been showing this, the Mexican townspeople along the way are helping them with blankets, with water, with diapers, with tissue paper, toilet paper, tortillas, what have you, because they feel a great deal of empathy for them. There may be others in Mexico who are not so happy, but the townspeople in Chiapas, and once they get to Wahaca it’s going to be the same thing, people are going to be helping them and supporting them. So, the Mexican government can’t just all of a sudden try and throw them out. There’s no way. It can’t happen. AMANPOUR: Well, let me quickly ask you to react to what President Trump also said, that, you know, if you take your cameras you’ll find MS-13 and Middle Eastern people. I mean, his own counterterrorism officials have said that there is no evidence for that. But are you concerned at all this might be a conduit for any kind of terrorism or anything like that? CASTANEDA: I don’t think so at all, Christiane. I was foreign minister on 9/11. We began cooperating with the United States with the Bush administration the next day on security. And over these now 17 years, there has been not a single incident of terrorists trying to enter the United States through Mexico or trying to enter Mexico through the land border with Guatemala. And the least — the last place they would want to hide, so to speak, is in the middle of a caravan where they have to walk in 30-degree heat or 90- degree heat, in American terms, and walk for over 1,500 miles and be exposed to everything that has happened. Why bother? They can get on a plane in Tapachula and fly to Mexico City. AMANPOUR: All right. Well, you’ve wrapped that up for us. CASTANEDA: They got a great deal of surveillance. That’s pretty simple, I think. AMANPOUR: So, let me quickly end on sort of broader issue and that is economic opportunity for people in your region. Of course, NAFTA and the whole renegotiation of the deal between the United States, Mexico and Canada. I mean, we know that — I think it’s something like 27 U.S. states, you know, their major, major partner for economics is Mexico, their destinations there. What has NAFTA done or the new negotiation? Is it wildly different than what it was before? Is the U.S. better off? Is Mexico better off? How would you frame what’s happened? CASTANEDA: I think I’d frame it with a huge sigh of relief, Christiane, in the sense that at least there is a new NAFTA instead of no NAFTA at all, which was a real threat, a real danger during many of the months of the negotiations since President Trump took office. That said, this new NAFTA or whatever anybody wants to call it, is really not that different, not terribly different from the previous one. And most importantly, it will not affect neither for better nor for worse the southeast of Mexico or Central America. The region in Mexico that the marchers are going through, Chiapas, Wahaka, maybe later Guerrero, maybe through Puebla and the La Cruz, are the poor states of Mexico, the poor south of Mexico, a little bit like in Mid Soggiorno in Italy. You know, these are very poor regions where you don’t have automobile plants, you don’t have refrigerator plants, you don’t have LED television, flat screen plants. You have people growing corn. You have people growing bananas. You have people growing nuts or some coffee sometimes and Chiapas. They’re very poor regions. NAFTA is not going to make a whole lot of difference. The absence of NAFTA would have been a disaster for Mexico, absolutely. Apparently, that has now — that danger has gone away except, Christiane, and I have to mention it, unless President Trump says, “If Mexico doesn’t stop these people I’ll rip up the new NAFTA and I won’t sign it.” And I would not discard that having followed President Trump closely now for two years almost. AMANPOUR: Golly. Well, I just was going to then ask you what you thought of the latest polls in Mexico, basically showing a drop of more than 30 points in positive views of the United States between 2015 and 2017. CASTANEDA: Well, it’s absolutely logical. I mean, he, as a candidate, Donald Trump, called Mexicans rapists, drug dealers, thieves. I mean, he ran his campaign on an anti-immigration, anti-Mexican platform. He’s doing it again right now, by the way, for the midterms. So, after a lot of goodwill in Mexico towards Barack Obama, even if Obama deported more people than any other American president had ever done, there was a lot of goodwill. Trump comes along and starts insulting Mexicans every day. Then he says he wants to build the wall. Then he says he wants to rip up NAFTA. Then he begins deporting Mexicans from the heartland of the United States, Christiane. It’s very different to deport somebody who just crossed the border and knows he’s risking money, his life, whatever, and will try again the next day to deporting someone from Chicago, Atlanta, New York who has got a family here, has been working for ten years without papers granted, he’s undocumented or she’s undocumented, but they’ve been living here, they’ve been paying taxes, they’ve been law-abiding citizens, low levels of criminality. They have a job. They have a home. They have children in school. And all of a sudden, they’re picked up and sent back to Mexico, a country they haven’t been to in 10, 15, 20 years. AMANPOUR: Jorge Castaneda, Former Foreign Minister, thank you so much for joining us. And so, as the Trump administration struggles with the right response to people fleeing violence and repression in these countries, so, too, is it struggling with the right response to a close ally, Saudi Arabia. Since the journalist, Jamal Khashoggi, was killed on October 2nd inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. It’s something the Turkish president, Erdogan, today called a premeditated murder. He said a plot that began in late September. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) RECEP TAYYIP ERDOGAN, TURKISH PRESIDENT (through translator): The information obtained so far and the evidence found shows that Khashoggi was murdered in a ferocious manner. To try to hide such a ferocious murder would be an insult to the conscience of humanity. So, we expect appropriate actions from Saudi Arabia. From this point onward, we want them to reveal all the parties responsible and to give them the appropriate penalty. (END VIDEO CLIP) AMANPOUR: So, the crisis has become a test of leadership, not just for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia but also for the United States, which is something my next guest knows all about. Retired Four-Star General, Stanley McChrystal. He led the U.S. forces in Afghanistan and the coalition forces and also the anti-terrorism campaign in Iraq before that. He taught a course on leadership at Yale University. And now, he’s written a new book about it, it’s called “Leaders: Myth and Reality.” And, Stanley McChrystal, welcome to the program. STANLEY MCCHRYSTAL, RETIRED U.S. FOUR-STAR GENERAL: Thanks for having me, Christiane. AMANPOUR: Well, you know, it’s really good to have you today because I think a lot of what we’ve just been discussing on a sort of geopolitical level and particularly now with the United States, you know, really implicated in this whole Saudi-U.S. relationship, what to do about it. And I’m drawing on your expertise as a leader in the field and now one — you know, you’ve written a lot about it. You have said that the U.S. has to stand up and say Khashoggi’s murder is wrong. So, what would you advise as a leading policy in that regard in answer to this? MCCHRYSTAL: Well, I think a long-term view is very important. One of the things I was reminded when I commanded in Afghanistan is we had a 46-nation coalition. Most of those other nations that came didn’t come because they had an interest in Afghanistan, they came because they believed in the United States, they valued the relationship with us. It wasn’t perfect but that was very important. So, what I’d say is, when we look at the Khashoggi issue, we do want to have a relationship long-term with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and we will. But it has to be based on trust. It has to be based on values. It has to be based on respect. Were we not to show the strength in that now, not to be demanding of our allies as we are of our enemies but also of ourselves long-term, I think we pay a huge price. AMANPOUR: Well, I want to see whether you agree with your former civilian boss, the Former Defense Secretary, Robert Gates, who — you know, we keep pushing all these leaders as to what they think is the best response, as they call it to thread the needle you are talking about right now. And he said, well, this administration could do worse than look back at what the George H.W. Bush administration did after the Tiananmen massacre in China or in Beijing in 1989. Listen to what he said. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) ROBERT GATES, FORMER U.S. SECRETARY OF DEFENSE: He was the first head of state to impose sanctions on the Chinese government to show that how much we disapproved of what they had done. But at the same time sent emissaries to the government to talk to the leadership in Beijing, tell them why we were doing what we were doing, why we had to do what we were doing, but that we wanted to keep the strategic relationship still on track. (END VIDEO CLIP) AMANPOUR: So, there are methods, right? I mean, this administration could just look back into the not too distant history book. MCCHRYSTAL: Well, I think so, and I completely agree with Secretary Gates. You have to tell them there is a future. But at the other time, you have to tell them there have to be levels of trust and values involved here. Or, in the near term, there have to be huge consequences for that. AMANPOUR: I want to ask you to just put your hat on and look at it from the Saudi point of view, again, with regards to leadership and what makes good leadership. So, we read that for decades and decades the Saudi royal family, the mosques, the — whatever, you can call it civil society or not, but nonetheless, the population ruled by consensus to try to keep the peace, and by and large did. But that this particular new crown prince has vacuumed up so much power and it’s all concentrated in one person’s hands, by and large, that, you know, this kind of thing may be allowed to go on. I guess I’m trying to ask you what you make of that kind of power dynamic in terms of leadership. MCCHRYSTAL: Well, often we confuse power and leadership. You can have an awful lot of power and you can exercise it through coercion or you can give rewards or things like that. It’s not really leadership in my view because leadership is something that makes people better. Leaders are people who pull us to higher values. They make us braver. They make us stronger. They make us more compassionate. They make us the things that we in our lives sometimes just don’t do. So, the temptation is to have political power or military power or economic power. But the long-term thing that makes a difference is changing how people think, changing the values they exhibit on a daily basis. And I think the Saudi have is taken a near-term view and they will also pay a huge price for that. AMANPOUR: But President Trump does tend to praise strong men, and I use that — you know, not gender neutral, it’s strong men. He likes that. He doesn’t actually like strong women like Angela Merkel but he does like strong men, to the point that he even while hinting that he wasn’t satisfied with the Saudi response to the killing of Jamal Khashoggi, nonetheless said the Saudi crown prince was in control and a strong leader. MCCHRYSTAL: That’s certainly what we’ve seen. I just spent the last two years studying and writing a book on leadership, and the big conclusion for me after all this time of thinking about it was that leadership isn’t what we think it is and it never has been. When we look back at leaders, we see leaders who grab on to either power or celebrity or zealotry or even their own personal genius and they confuse that for being real leaders. And being real leaders means you have an interaction, a relationship with your followers that makes both better. It makes the leader better. It makes the followers better. And it constantly adapts to the situation. So, if we think of leadership or power as two-dimensional hammer that we pound on people until they get it, I think we really get a bad outcome. AMANPOUR: I’m going to get to some of the specifics in your book in a moment. But I want to ask you about the concept of dissent because whether it’s in a political context, a military context, and what it actually means. How do you — where did you come down on the concept of dissent? [13:30:00] I mean, you know, we have to sort of throw back to – to your sort of running against some kind of dissent. I mean you were forced to retire because of words that you used, words that your subordinates used that got back to your civilian boss. And that was the president of the United States, and he said no, not dealing with you, General, you know. So where does dissent play? MCCHRYSTAL: Yes, I – I think dissent’s incredibly important on two levels. On a personal level as you get more senior powerful, you become a four star general. There’s a tendency for people to laugh at your jokes, say how smart you are, underwrite what you say because it’s just the dynamic. You wear your rank on your uniform. The danger with that is you start to believe that you are smart, that you are humorous, that you are all these things and your courses of action are right. You really need dissent around you that says hey, guess what Stan? You go this completely wrong, and you have to construct people around you that did that for you. You know, I got married, that’s worked to my personal life for many years. But – but in a professional sense, you have to do that thoughtfully, you have to create it. On a national level, dissent has to be welcomed and celebrated. If somebody stands up and says no, I think we got it completely wrong and here’s my reason, if we criticize, if we stomp it down, not only do we lose the value of that particular message, which may or may not be right, but we cause a lot of other people to be more hesitant to dissent. There’s always a certain group of people who, if they see someone else get attacked or publicly shamed or embarrassed, they won’t raise their hand. And suddenly what we have is a quieting of the population. We start to create sheep and a nation sheep is a dangerous place. That’s not the American tradition, it’s not what we want. We want a vigorous national debate, but it’s got to be by people who are respected and respectful. AMANPOUR: OK, so that raises a couple of questions, first the idea of not tolerating dissent is apparently what got Jamal Khashoggi killed. He was a reformist, he believed in the crown prince’s reforms, but he believed that there should be a bigger consensus and bigger debate and he believed the power was being too concentrated. But what about the United States? Do you believe the United States in the Trump era is a nation of sheep? Do you believe that Congress is a gaggle or a pack or whatever these sheep are in the plural? Do you believe that if the military, the uniformed military of the United States is given an order that they may not believe is a legal order, should they refuse it? MCCHRYSTAL: Well for the military, I sure (ph) to take that off the table. I’m not on active duty anymore. If they get an order that is illegal, they absolutely are required not to follow it. So I think that’s separate. I think our political leaders, some of our social leaders, I think a lot had been quieted. I think I have a lot of conversations with people who have misgivings, but they say you know, but the economy’s doing well or but we got this that we like or but we got that that we like. And the danger is as we attack the media or we attack our political opponents or we put names that is publicly shaming or embarrassing to people, we start to over time cause people to be more and more reticent to say anything. You know, if I know I have to be teaching, I’ve been teaching almost nine years now, if a student asks a question or makes a constructive criticism in the class, and I sort of slap him down with a smart response, you know, I may feel good for that moment but I lower the – I lower the likelihood any other student’s going to say anything, much of what might be very valuable. AMANPOUR: Let’s just quickly go back over your recent military history. I mean you were JSOC in Iraq, you did catch Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was the leader of the ISIS iteration there, the Al-Qaeda iteration in Iraq. That was a success. Then you led troops in Afghanistan, and frankly it’s currently not a success. I mean Afghanistan is the longest war, we’ve seen the highest number of civilians being killed there in a – in a long, long, long time. We see the Afghans even making the – the killings of their own forces a secret, like a national security secret. What is – what is going wrong? I mean this is a of money, nearly a trillion dollars, so many thousands of troops, so much death, so much injury. MCCHRYSTAL: Yes, and Christiane, you’ve been there. I know there’s a tendency to paint with a broad brush from afar and see Afghanistan as a violent place with bearded mullahs, war lords, and the Taliban and corrupt officials. And that’s not untrue, but if you get close, you see an unpreceded (ph) number of females in school. Now for 17 years, ever since 9/11, you see a new generation rising. It is not perfect, it’s not even on an (inaudible) to get to perfect in my lifetime, but what it is, is it’s an effort by part of that population to have a better future. [13:35:00] Now if we made a strict business case I could say we should walk away from Afghanistan, sort of wipe our hands of it and say that’s – that’s money wasted. That might be true and it’ might be lies but I don’t think that. I actually think that when we make an effort to give people hope, when we make an effort to give people opportunity, when we try to communicate around the world that getting stability and getting opportunity in an area like this, I think it’s an investment that over the very long term plays off. I think the United States is actually been using – living off some of the things that were done for decades before now that built up a level of confidence and good will in our nation. So there is no easy answer in Afghanistan and I wouldn’t be arguing to put a lot more troops or do anything like that but I think a partnership with the people of Afghanistan and clear communication that we’re involved in the region because we care does make a difference. AMANPOUR: I want to go back to your book because you have profiled 11 leaders, the vast majority of them are men and you profiled maybe 3 women. You talk about people like Coco Chanel, Walt Disney, Robespierre, as I said Abu Mausab al Zarqawi, Harriet Tubman, Zheng He and Robert E. Lee. You also say that you realize that there just are not enough women in your book and not enough women. You say it’s unhealthy as, well sort of immoral, or whatever the right word is that you used. Why? MCCHRYSTAL: Well because women have traditionally been underrepresented in leadership positions. We have an interesting finding. It wasn’t surprising to find out that there are more male CEOs in America than there are female CEOs. It was surprising to find that there are more male CEOs named John than there are female CEOs. So there just haven’t been the avenues. The few we selected, Margaret Thatcher, Harriet Tubman, Coco Chanel were all different nationalities, completely different backgrounds and all had a very tough road to leadership. The grocer’s daughter, Margaret Thatcher sort of works her way through a complicated British political system to become the most famous Prime Minister outside of Winston Churchill in the 20th Century. She has a whole era named after her. Harriet Tubman, five foot tall African-American former slave goes back 13 times into slave-controlled territory to rescue other slaves. She’s not a particularly outgoing woman. She speaks but she speaks for a larger cause but she’s got this extraordinary ability to become a symbol for others, not just females but also for African-Americans and for everyone. And of course, Coco Chanel, comes out of an orphanage and she founds an empire and she does it by making people want to be like Coco Chanel and others to want to work for her. AMANPOUR: You know I never thought I would be talking about Coco Chanel with General Stanley McChrystal when we met in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nonetheless, it’s very refreshing. But can I just end with something – your own personal sort of epiphany or road to Damascus. For a long time, General Robert E. Lee was your hero and you say you describe the great hero Winston Churchill as praising him as one of the best battlefield commanders and at the age of 63, you decided to ditch that. Why did it take you so long? MCCHRYSTAL: You know I think it takes all of us a long time. I admired Lee, the General, for all of those sort of traits that you have — honest, courage, decisiveness on the battlefield, and I was encouraged to do that. In my youth I went to Washington and Lee High School. I went to Lee’s college, West Point, but then what happened is after Charlottesville I realized that Lee’s persona often shown in painting or statues had been hijacked. It was being used by a part of America with white supremacist (ph) and other views to send a message that I don’t associate myself with. AMANPOUR: Right. MCCHRYSTAL: So I stepped away. I don’t think he’s horrible but I think we have to have a mature view. AMANPOUR: And that too is leadership, knowing when to step away. General McChrystal, thank you so much indeed for joining us. And now, we turn to a conversation with a great leader in the field of quantum physics, Professor Brian Greene is a world-renowned physicist and a best-selling author who’s creative storytelling helps make complex scientific theories accessible to a general audience and he sat down with our Walter Isaacson to talk about the biggest scientific mysteries of our time and how quantum computing could drastically alter our future. [13:40:00] (BEGIN VIDEO TAPE) WALTER ISAACSON: Brian, welcome to the show. BRIAN GREENE, THEORETICAL PHYSICIST: Thank you. ISAACSON: If you could solve three scientific problems, tell me what they’d be. GREENE: Very clear what they would be. So I want to know the origin of the universe — I want to know the origin … ISAACSON: Origin of the universe and we’ve gotten a little bit closer. GREENE: We’re closer — we’re closer but if you were to say to me so why did it start at all? We still don’t have an answer to what happened at time zero. It’s an origin of the university, origin of life. How did these particles coalesce and come together to yield living, breathing things like us. Again, we’re getting closer but certainly we can’t create life in the laboratory yet. When we can do that, then I would say that we’ve really cracked that problem. And the third is the origin of mind, the origin of consciousness. As we were talking about, how is that particles that don’t seem to think on their own; electrons and corks. Do they cry, do they have emotions? I don’t think so but somehow they all swirl together and here we are having an inner life that somehow lights up. What turns on the lights in there? I don’t know. ISAACSON: Explain to me how quantum computing works. GREENE: There actually are small quantum computers in existence now. So this is not just pie in the sky. If classical computer, the ones that typically use, it goes step and step and step and step. Everything is sequential and everything is definite. In the quantum world you can do all of these fuzzy calculations at the same time and have them coalesce into the answer that you’re seeking, which means you can do the calculations far more quickly. You can do the analysis far more quickly. You can tackle problems that a classical computer couldn’t touch. What would that mean for our lives? To me that the real — the real possibilities of quantum computing are to undertake problems of today we simply couldn’t even approach using classical ideas or which we will take to a spectacularly new level. I mean one that comes to mind is machine learning. So machine learning has the capacity to transform everything. And we are used to having devices be it a bulldozer or a jackhammer that extends the power of the human form to do things that otherwise would be impossible. But that’s just sort of a stronger, faster, leaner version of ourselves if you would. It doesn’t really replace creativity in the human intellect. Machine learning, many people suspect, may be able to do that. When a machine can actually look at large data sets and not me told how to analyze them but learn by seeing the patterns that’s what we do, we are pattern recognition machines and when a computer can do that, then we’re in a completely different arena. And that we see starting to happen and quantum computing is a very powerful means for recognizing patterns to dealing with large data sets. So this is at least — you know its decades off but this could be a place where we begin to really see computers doing the things that for the most part, for all of human history, we have viewed as intrinsically us. ISAACSON: And that includes creativity, you said. GREENE: I think so. ISAACSON: But it seems to me creativity means something a computer couldn’t do, which is thinking outside of a rule. Tell me why that’s (inaudible). (CROSSTALK) GREENE: Well, we like to say that because we like to think that we’re special and I don’t mind the human species being a special entity in reality but the fact of the matter is, creativity may well be seeing unusual and hidden patterns within data, manipulating those patterns to a powerful effect. And that happens inside this thing inside our head, this grey gloppy thing and I think it just operates by the rules of physics. And if it operates by the rules of physics and doesn’t have any other kind of inspiration, why can’t a device outside of a grey gloppy thing inside of our heads also undertake those very same kinds of calculations, computations, and analyses (ph). So I think it’s very possible that one day they’ll be somebody in that chair who is able to carry out this kind of interview that we’re interview that we’re having and certainly somebody will do a better job than I am right here. And that is when we cross a threshold into a brave new world (ph). ISSACSON: That gray gloppy thing you referred to, it has consciousness. Is consciousness explainable by physics? GREENE: I think so. I don’t have any proof of that. Now we’re just in the territory of gut feel at the moment. But again, I don’t think there’s anything going on inside our heads that isn’t ultimately the motion of particles and the oscillation of fields (ph) and we have equations that describe those processes, they may not be the finale equations. One day perhaps we will have them but I don’t think we (ph) need anything else but physical law to describe ultimately what’s happening inside of our heads. [13:45:00] And from that point of view, consciousness would simply be a quality of the physical world when there’s a certain kind of collection of particles that come together in the right way and perform the right operations. ISAACSON: You’ve been working — whether it be string theory and other things — on trying to capture what Einstein wanted to do. Which is a unified theory that would connect quantum to gravitation to relativity and everything else. If we had a unified theory, wouldn’t we — wouldn’t it all fit together again and not everything would be probabilities? GREENE: Well, if you believe Albert Einstein’s vision, then indeed that’s where we would be heading. Einstein thought that if we could just get a unified theory, all of this quantum stuff — that was certainly working at describing the data, he couldn’t deny that. But he thought it’s just a stepping stone to the deeper understanding and when we get there, no more talk of probabilities, no more talk of entanglement, no spooky action. That’s what he thought. But you know, he passed on a while ago, right? 1955. And in the half century since, every single piece of experimental data, every single mathematical development has pointed away from that vision. The vision that we have now is that the quantum world is here to stay and just accept it and get on with it, because having that old vision is coming from an intuition that was built up over a long course of human history, but it’s the wrong intuition. ISAACSON: So you don’t think there’s a unified theory? GREENE: I do think there’s a unified theory. I don’t think it will accomplish what Einstein hoped it would. ISAACSON: In other words, we’ll still have uncertainty — GREENE: We’ll still have quantum uncertainty and we’ll still have quantum probabilities and all this weird quantum stuff will still be with us. The advantage of the unified theory is finally we’ll put together our understanding of gravity and our understanding of quantum physics into one unified whole. That would be progress. But I don’t think that progress will wipe out the quantum understanding. ISAACSON: The other great advance in the past couple of years was cosmic background radiation came along. What did that explain to us? GREENE: Well the cosmic microwave background radiation is our most powerful insight into cosmology. We all want to know how the universe began. And again, with Einstein’s general theory of relativity updated by more sophisticated versions of the cosmology that it gives rise to in recent years, we have a pretty good sense. In the early universe we believed that there was a kind of repulsive gravity that drove everything apart, rapidly stretched the fabric of space. And when we do our calculation, that stretching would have also stretched out little, tiny quantum uncertainty in the early universe. Sort of like if you have a piece of spandex. When you stretch out the spandex, you can begin to see the pattern of the stitches. We believe that we can see the stitching of the fabric of space through the stretching, and that is the microwave background radiation. And we can do calculations that predict how the stitches should look, tiny temperature variations across the night sky. And holy smokes. When we do the observation and we compare it to the calculations, they’re spot on accurate. We’re talking about processes that happened 13.8 billion years ago — ISAACSON: Wait, wait. So 13.8 billion years. GREENE: Yes. ISAACSON: Something happened. And then what? This wave came and it finally hit us? GREENE: That’s right. That’s right. When we look up in the night sky and see the microwave background photons, they’ve been traveling toward us for over 13 billion years. And those little tiny packets of light have just the right properties that our mathematics predicted they should. So we human beings crawling around on this little planet 13.8 billion years later are able to develop equations that seem to give us insight into processes that happened billions of years ago. ISAACSON: So what does that tell us about how the universe began? GREENE: Well, we think it probably began as this very compressed, tiny nugget that was filled with an exotic cosmic fuel. We call it the inflation field (ph). The name doesn’t matter much. But it’s a fuel that gives rise to an exotic kind of gravity, this repulsive gravity that pushes everything apart. That’s the bang in the big bang and we’ve been living through the aftermath of that cosmic explosion ever since. And the only reason why we believe these ideas is because of microwave background radiation so completely agreeing with what our predictions say it should look like. ISAACSON: You know, the cosmic background radiation helps understand what happens in black holes. That’s been one of your fascinations, which is the edge of black holes. First of all, let me ask you about your “Icarus at the Edge of Time”, how you try to explain that through art, through children, through music. GREENE: Yes, well I think that these ideas need to be widely understood, widely discussed, widely shared. And so if they stay within the hallowed halls of universities or esoteric journals, it really doesn’t get out there. So we’ve tried various — you know, unusual blendings of science and art to try to reach a broader audience. In this piece you’re referring to, I collaborated with Philip Glass. I wrote a short story. [13:50:00] Journals, it really doesn’t get out there. So we’ve tried various, you know, unusual blendings of science and art to try to reach a broader audience. And this you’re referring to, I collaborated with Philip Glass, I wrote a short story. It was a rewriting of the myth of Icarus, where the boy doesn’t go near the sun with wax wings. He built a ship and flies through the edge of a black hole. And what happens is near the edge of a black hole, time slows down. So when he comes back, thousands of years have gone by on earth, but only a couple hours for him. So his dad is gone, his family’s gone, so it’s kind of a traumatic story. But Philip liked it and we turned it into a live stage work where there’s an orchestra, a film and a narrator that kind of takes the audience to the edge of a black hole. (BEGIN VIDEO CLIP) UNIDENTIFIED MALE: We’re navigating to avoid an unchartered black hole. A black hole? Cool. (END VIDEO CLIP) And when you have that kind of experience, it doesn’t just make your head hurt it kind of makes your – your heart pound, right? If you get into the story, you can feel the chill of the experience. And I’ll tell you – you know, let me just tell you one thing, my son when – when he first encountered the story that I wrote, at the end he was crying. And someone said well don’t you feel bad? You wrote this story that made your son cry because the dad is dead. And so I said no, if general relativity which is ultimately what’s in this story can make a five year old cry, it’s a good thing. That kid is feeling the science. And you need to feel these ideas in order that they aren’t just esoteric, abstract nonsense. ISAACSON: So much of this stuff is not something we can apply in our daily lives. We’re never going to go near the edge of a black hole, we’re never going to travel near the speed of light. Why is it important that we understand it? GREENE: Well my own sense is that the universe is incredibly rich and you don’t have to know these ideas to live in this world. My mother doesn’t know these ideas. She says they give her a headache, and I totally get that and I respect it. But if you can get these ideas, it opens up a reality in wondrous ways. I mean to walk down the street and think that time for you is elapsing at a different rate from somebody on a street bench, right? To look up into the night sky and be able to think about the quantum processes that do give the microwave background radiation. To think about quantum physics, allowing us to tunnel through barriers or have these strange, spooky connections, it’s just wondrous. And how tragic if people are cut from these ideas simply because they don’t speak the language of mathematics and physics. That’s why I think these ideas need to be brought out to the world in many various ways. ISAACSON: Explain to me, though, that notion of you walking down the street and you’re saying to yourself time is traveling for me differently than this person moving in the other direction? GREENE: Yes, well you know I’ve tried to see what it would be like to live these ideas. So at times I’ve forced myself to go around the world and really imagine in detail what’s going on, the time and the space and the quantum physics. And yes, one of the key ideas of relativity is when you move relative to somebody else, your clock is ticking off time at a different rate. And it is very hard to hold these ideas in mind, because you are assaulted all the time by conventional reality telling you that all clocks tick off at the same rate, which is wrong. It’s false. But it’s hard to live with the truth because so much of your experience contradicts it, it’s counterintuitive because these effects are very small in everyday life. But I find there’s something deeply wondrous every so often in actually living these ideas. ISAACSON: So if I walk down Broadway today, what am I supposed to observe and watch and think? GREENE: Well first of all, recognize that the sidewalk is mostly empty space and that you’re actually not touching the sidewalk because it’s actually the electrons in your shoes that are repelling against the electrons in the concrete. So you’re floating as you’re walking along Broadway. And yes, your time is elapsing at a different rate than someone who’s sitting relative to your motion, your time is also elapsing at a different rate from someone who’s at the top of the Empire State Building. Your watch is going slower than theirs. ISAACSON: Because their gravity is different? GREENE: Their gravity is a little bit less. ISAACSON: And so why – why is that? GREENE: Well the answer comes from Einstein’s theories. I can imagine a world where that isn’t the case. So it’s not like I can say logically it had to be that way, but in Einstein’s general relativity, gravity doesn’t just pull on matter, it also pulls on time. And when it pulls on time, it makes time elapse more slowly. So at the surface of the earth where gravity is a little bit stronger, the pull is stronger, time goes slower than at the top of the Empire State Building. Yes, it’s crazy. ISAACSON: Brian Greene, thank you, pleasure. (END VIDEO TAPE) AMANPOUR: While my time may be elapsing at a different rate than yours, this still is all the time we have for our program tonight. Thanks for watching ‘Amanpour and Company’ on PBS and join us again next time. END |