Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Hello, everyone. And welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY. Here is what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMINA MOHAMMED, U.N. DEPUTY SECRETARY-GENERAL: This is not is Islam. I am educated. I am working. And there’s nothing in my religion that stops from

doing that.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Working to reverse the Taliban’s crackdown on women’s rights. I speak with two of the United Nations most senior officials just back from

Afghanistan. Then.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREW SOLOMON, AUTHOR, “FAR FROM THE TREE”: I struggled a lot with the sense that I was somehow broken or damaged, and that I belonged at the

margins, and that I would never have the basic satisfaction of life.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The power of love and respect for those on the margins of society, with the author Andrew Solomon, whose bestselling book, “Far from

the Tree” is now a film. And, a cousin remembers the tragic death and legacy of the civil rights martyr Emmett Till.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Afghanistan was facing a humanitarian crisis even before winter set in. But now the country is enduring its coldest weather in 15 years, freezing

temperatures have killed well over 100 people. And as always, the crisis is hitting women and children the hardest, particularly after the Taliban

prohibited women from working for aid organizations, effectively denying them critical assistance.

So, in the past weeks, multiple delegations from the United Nations and other aid groups have traveled to Kabul to press for women’s basic rights

to work and to learn. I have been speaking with two of the United Nations most senior officials, who have just returned from a tough assignment

trying to get the Taliban to change its mind. Amina Mohammed is deputy secretary-general of the U.N., and Sima Bahous is the executive director of

U.N. Women.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Welcome both to the program. You have been to Afghanistan. You are the most senior U.N. official to have been there. And I guess I want to

ask from the get-go, do you have any hope, Amina Mohammed, that these draconian restrictions implied and imposed by the Taliban will be lifted?

AMINA MOHAMMED, U.N. DEPUTY SECRETARY-GENERAL: Yes, I do. I mean, I said it was tough going in, but I feel now it’s doable. Looking at all of the

players and seeing some of the fissures within the Taliban, I think this is possible. We’ve also had a few exemptions since then. So yes, there is

hope.

AMANPOUR: Let me ask you first about the fissures within the Taliban, because I’ve been told that as well, and I’m interested to see U.N.

officials and other officials actually not being afraid to call it out. So, it’s the Kandaharis, right, the fundamentalists who are sending down these

edicts. Is that right?

MOHAMMED: Yes, I think it is. I mean, that is where the power base is and the rest deployed. And I think that there is any change from their

consolidation around their power base. But there is in terms of carrying out some of these edicts, differences of opinion. I think in our visit, we

— it was very clear that recognition mattered. It was very clear that the humanitarian response that the International Community were giving was very

important. And so, we have some leverage, and I think that that’s what we were trying to see. As, you know, what is the state of play in reality on

the ground?

AMANPOUR: What does that, Sima Bahous, as head of U.N. Women? What does that mean, set the scene?

SIMA BAHOUS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, UN WOMEN: I think what they told us is that they want — when we talked about the edicts and diversing the edicts,

they said they needed time and that they said that these edicts are until further notice. And when we asked what is this further notice, they said we

need to build the infrastructure, we need to build the schools, we need to train the teachers, we need to change the curricular for it to become less

western — or actually not western at all, but Islamic and according to the Sharia of what they believe women should learn.

AMANPOUR: OK.

BAHOUS: They believed that women should only learn certain things about the Sharia and how to be — how to serve their husbands, their families,

and their little community where they live.

AMANPOUR: So, that seems to be a nonsense. There are plenty of schools that are built. You can easily put women in one class and boys in another

class and the rest of it. The curriculum, you know, it’s tragic. Would that satisfy the U.N. in terms of the bar that you set for respect of women’s

human rights? If they start doing all of this stuff, suddenly do you re- engage with them?

BAHOUS: We are already in engagement with him, to try to talk to them about what needs to be done for women. But I think what we need to continue

to do is to bring the voices of women and girls to them. And this is what the girls and the women we met asked us to do. They said, please talk to

them and let them understand where we are coming from. We want to see them. We want to engage with them. We want our education back. We want to go back

to work. We don’t want to be erased from public life.

And this is something that will eventually — this is what will make us accept what is going to happen. And we will work on that, all of us,

whether humanitarians or developmental or political even.

AMANPOUR: So, before we get to the actual fundamentals of what this ban by the Taliban means for all of you and for their humanitarian situation. What

did you hear from women? What do you know is happening to women there right now trying to survive this draconian existence?

MOHAMMED: Exactly, trying to survive. And I think that is the big message for all of us, that everything that we are doing there obviously is not

enough because there isn’t a space to do it. And with that shrinking space, it’s even worse. And we did speak to the voices of women on the way in who

want to go home, who want to be back with their families and in their country.

But the ones that were most painful to hear were those that were affected by the withdrawal of all of the activities and services and means of

livelihood because of these edicts. Ones that didn’t know if they would eat tomorrow. Others who were — female head of the households, where they were

the responsible for their children, their father. I mean, one had a father who had a mental health issue.

Others, the great level of depression shocked me. And I think that, you know, anxiety, no hope, those stories were very powerful, they were very

painful, and very real.

AMANPOUR: And I’ve heard that too, a lot about the depression. I mean, I’ve heard equally awful things reported by various, you know, news

organizations that some families are having to basically give their children medicine, to drug their children, to ward off the pain of hunger

and the, you know, the wails and the cries of hunger. Did you hear any of that kind of stuff or how the poverty is affecting them, if they can’t

support their families?

BAHOUS: Yes, we did not hear that on the medication. But we heard that many women cried in front of us. They — in the meetings, they start being

strong and resilient, and you salute them for that, but halfway through the meetings they crash and they start crying and then they tell us about,

like, two days, three days, they haven’t had food for their children. We have seen and we were told that there is higher levels of suicide taking

place. One woman told us that she has severe depression but she can only take one pill every three days because she cannot afford to buy these

things.

So, it’s really extremely, extremely powerful and extremely painful. And the poverty, and the cold weather that is —

AMANPOUR: Yes.

BAHOUS: — they are living through there now, the snow, the lack of actual support from the communities. OK. Women used to support each other through

women to women spaces, through friendly spaces for women. Now they can’t do that. They can’t go out unless their Mahram is with them, this man who is

supposed to guard them.

AMANPOUR: Guardian.

BAHOUS: The guardian, yes. And then —

AMANPOUR: Which could even be their young son —

BAHOUS: It could be —

AMANPOUR: — or nephew.

BAHOUS: Anyway —

AMANPOUR: Somebody younger —

BAHOUS: Absolutely, absolutely.

AMANPOUR: — taking their mother or their older sister or their aunt.

BAHOUS: And this, they told us, that it has also increased the control of men over them. Because if the man decides he doesn’t want to go out of the

house that day, then the women cannot go out. And, you know, many of them also lost their livelihood.

We went in Herat, to one of the centers where these women were getting training, where they were getting small scale income generating activities,

where they were hoping to make more money to go back to their university degrees, or to their even diploma degrees, but they told us that this all

stopped now. They can’t have an income generating activities. Nobody is coming. The centers are closed. Everybody is afraid. And this is a cycle

that we have never seen any other country in the world.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you, here you are, two prominent and senior women. I mean, the U.N. is about the only entity engaging with Afghanistan now. It’s

not recognized by any other country. And you are there to help, you know, so that it’s not collective punishment against ordinary defenseless

civilians. How does it make you personally feel?

MOHAMMED: It’s very tough. I mean this is a signal for one part of the world, but it’s happening in other parts. And so, for me, it is the

regression of women’s rights. When you are up front and center listening to people in another century, it’s very difficult. Our job is to try to bridge

the reality with the aspirations that we have, and that is tough.

We spoke to the hospitality and listening ear of some of our ministers that were there in Afghanistan. but we also spoke to some that, when they got

irritated and we pushed back, said, well, actually, haram that you should even be here. And you still have to be composed —

AMANPOUR: To you?

MOHAMMED: Oh, yes. And you still have to be composed and get through that meeting because you remember the face of the Afghan women, and what you

need to do for them. And I think that’s the most difficult, is you got all this rage and frustration, and you’re trying to get through it because you

are a Muslim woman. And as a Muslim woman, this is not Islam. I am educated. I am working. And there is nothing in my religion that stops me

doing that.

AMANPOUR: And when you say that to them, that here you are trying to, you know, bring in what you call, or what, you know, the so-called emir in

Kandahar thinks is pure Islam, which basically means the total oppression of women. When you say, but I’m a Muslim. What do they say?

MOHAMMED: Well, the thing about it is that they see this from the view of protection, where we see it from oppression. It’s a really important nuance

because when you are speaking to them, that that’s all they see. They will give you analogies of what that means. And we will sit there thinking, this

is just out of the world — out of this world.

We have got to travel them into the 21st century. That is what we have to do. And I think that kind of a mind you can’t have a conversation with on

what’s right and what’s wrong, it’s so fixed. And so, I think it’s really important that the engagement we’ve had with the OIC, the Organization of

Islamic states, it’s really important for them to come forth.

AMANPOUR: And are they? Are they stepping up?

MOHAMMED: Yes, they are.

AMANPOUR: I mean, we had Former Prime Minister Gordon Brown on our program who said very loudly and clearly that all the Islamic states should be

sending delegations, or — you know, what I mean. But impressing upon the Kandaharis and the Taliban, that this is not Islamic.

MOHAMMED: Yes.

AMANPOUR: That Islam does not ban the rights, and certainly not the education of women and girls.

MOHAMMED: Well, they sent these messages that were sent by Indonesia, largest Muslim population, sent by Turkey, sent by the OIC, Saudi Arabia.

So, we are hearing these voices. And I think this trip is about building that momentum on the different strands that have to somehow interact and

get a unified international front so we can begin to put the pressure and take the actions that we need.

We saw a leverage, they do want recognition. We saw leverage, they do want the humanitarian assistance. What we have to make sure is that we travel

that path so that the women don’t suffer doubly.

AMANPOUR: So, tell me then, you’ve talked about trying to mitigate the pain, because now if women are not allowed to work, although apparently

they are allowed in the U.N. right? They are allowed into the humanitarian space for the U.N. Is that right? What are the exemptions in other words?

Set me straight.

MOHAMMED: Exemptions, I mean, the pressure of our partners and the international NGO world and with some of our governments, has been such the

exemptions that given in the medical field. So, your doctors, your nurses – – I mean, for goodness’ sake, you can’t deliver a baby online, right? So, we have to have women to women, and that service is open now. It’s

implemented differently depending where it is, but they have issued an instruction that women can go into that space.

AMANPOUR: But if — to be fair I was there in ’96, Taliban1.0, and women were doing that.

MOHAMMED: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Because it couldn’t be men delivering women’s babies, right?

MOHAMMED: Absolutely, but also —

AMANPOUR: If they want to separate —

MOHAMMED: — but also in other medical services as well. And in being able to transmit some of the light saving materials, they are allowed to teach.

Remember that primary education is allowed, and only 23 percent of kids have access. It’s not a question of there are classrooms, there aren’t. So,

it’s an opportunity for us to put the investments in there and catch them young so the next generation are a foundation that we know we can build on.

But the secondary schools and the universities that are there and available should be open to all women and girls. So, there are exemptions to the

teachers. There are exemptions in the medical side and health side.

AMANPOUR: Uh-huh. I want to ask you about the teachers because it’s the education that sent the world into an, you know —

BAHOUS: Right.

AMANPOUR: — apoplectic fit, and rightly so. I was reading that, you talk about they want to do new curriculums, and this and that, Sharia based

curriculums. But I was reading that the, “Taliban leaders” — this is a quote from a news article, “are now raising a new generation of violent

extremists. They’ve commandeered the Afghan school system, installing new curriculums that indoctrinate children in their extremist ideology.

Endorses violence to advance their objectives, growing friction within the Taliban” — you know, “will make further radicalization inevitable.”

Are you concerned about that? Are you concerned that whatever curriculum they want to change, and they’re telling you that, is not exactly a good

curriculum?

BAHOUS: Yes, we are concerned. And I think what we need to do is to continue to engage with them, to make sure that this curriculum of

violence, of extremism, does not come through. I hope that we will be successful. We don’t know that we will be, but it is important that we

continue to engage and explain to them that this is not, as Amina said, if you want recognition from the world, this is not the way to go. And if you

want recognition from the world, violence and extremism and all this and terrorism is not going to work.

Also, the countries around them are also going through this to them. They are worried about terrorism, they’re worried about refugees, they’re

worried about narcotics, they’re worried about — you know, the Taliban exporting to them all of these ideas. So, we will also, we will continue to

work with the neighboring countries to ensure that this does not happen at all.

And also, to make sure that whatever it is that they do, and they’ve — they come up with in the end is — brings women back to the public space,

to the schools, to the workplace where they belong, just like men do and boys.

MOHAMMED: When they speak to us, they talk about the progress that they have made, and there’s been no recognition of that. And I think that’s the

fear, is that you have to have a push and pull.

AMANPOUR: And what is the progress from your point of view?

MOHAMMED: Not from my point of view, from what I’ve heard, because they give some rights and they take with the other hand away others important.

They’ve had laws that they’ve congregate which gains (ph) gender-base violence. Give inheritance back to women. Have stopped the blood money

exchange for women. Have created that amnesty space, but we have to see them implemented.

When we talk about the exemptions, we want to push the exemptions. But it is of concern because what you have is a bunch of fighters that have come

back after 20 years. If they are not re-oriented and given skills to join, what we would say, as the full workforce for a better Afghanistan, they

pose a huge risk. A risk for what could happen to the country itself in extremism, but also another risk for women because you have then the

violence that they will perpetrate. And we’ve seen an increase in gender- based violence in Afghanistan since.

AMANPOUR: To be fair, you have said while you are still there, before you came and joined us here, that you think no matter what progress you might

make, it’s a long way in the future, right? It’s a long road to try and get all these things that you have just described actually to fall into place,

to reverse these bans.

MOHAMMED: It’s a long haul. I mean, we have to acknowledge right now that the people in power are the Taliban. And for us to engage them, holding on

to the principles and the leverage of recognition, whatever other support is a difficult one. But it can be done. There is a division of labor.

I mean, even when we talk about the madrasas that now with the curriculum that they have, that could turn a whole generation of children into

terrorists. We have Indonesia who developed a madrasa system that moved away from that. They are engaging. Could they engage, since they are

speaking together, to turn that away?

So, yes. It’s a long haul. It’s a step of the humanitarian. It’s a political track. It’s also engagement that really sees a socioeconomic

piece that empowers women. And I think that, you know, we can pull, as you know, from Islam. That Islam itself was funded because of the business

acumen of a woman, the wife of the prophets. (Speaking in a foreign language).

AMANPOUR: Amina Mohammed, Deputy Secretary-General, Sima Bahous, head of U.N. Women, thank you both for joining us.

BAHOUS: Thank you.

MOHAMMED: Thank you for having us.

BAHOUS: Thank you so much.

MOHAMMED: Thank you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Human rights are under fire all over the world and in the west, particularly in the United States where new state laws target gay, trans,

and minority populations. In his nonfiction hit, “Far from the Tree”, the author, Andrew Solomon, brings empathy to those on the margins. Sharing

stories of families who are raising children who challenged society’s definition of normal.

Now, he’s here in London to present the documentary, based on his book, at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival. And here is a clip from the trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: All parents deal with children were not what we imagine. My parents really did not want to have a gay son. I wanted to see

how other families managed that. But I don’t want to just know about families of gay people. I wanted to look as widely as I could.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And I spoke with Solomon about the remarkable social progress he has experienced, and the backlash that threatens to undermine it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Andrew Solomon, welcome to the program.

ANDREW SOLOMON, AUTHOR, “FAR FROM THE TREE”: What a pleasure to be here.

AMANPOUR: And you are here in London and you have screened the documentary, “Far from the Tree”, for Human Rights Watch. I’m interested to

know why. Why that film? Why Human Rights Watch? What’s the connection?

SOLOMON: I have been very involved with two programs with human rights watch, the disability program and the LGBT program. And they are

particularly strong in both of those arenas. You know, if somebody who has the disability to mental health complained and who is gay, I am very aware

of how the rights and privileges available to me are unavailable to people in most of the world.

AMANPOUR: So, the interesting thing is, “Far from the Tree”, it’s about parenting and surprise, you know, surprises that can develop in parenting

and children.

For example, parents of queer children, deaf children, those with dwarfism, et cetera. What do you see has changed in the years, the decades since you

wrote the book?

SOLOMON: Well, there’s no question that people are more aware of disability rights. That the idea of disability rights has been validated

and the notion that the lives of people with disabilities have their own valor and their own value. The life with disabilities aren’t automatically

ones with our project. That has come to be more in the public conversation.

On gay rights, gay marriage is spreading. It’s become more ubiquitous, but there are still so many examples of terrible prejudice in parts of the

world where homosexuality is not accepted. But also, in the U.S. and in the U.K., and in other major developed countries, problems for people who want

to have families, problems for people who get fired from their jobs, problems for people who do not get the housing they want. And an enormous

amount of violence that is directed against LGBTQ people who, in most of the world, had very little protection.

AMANPOUR: And especially children because I have seen some of your other articles, that you know — I mean, maybe adults can deal with it somewhat

better than children. You also had that experience in your childhood, right?

SOLOMON: I did. I was very secretive about the fact that I was gay, at least I thought I was being secretive. And I had a family that was not

pleased when I finally came out in my early 20s and I struggled a lot with the sense that I was somehow broken or damaged and that I belonged at the

margins, and that I would never have the basic satisfactions of life.

The idea that I would end up married to a man with a family was not only something I failed to mention. It was something that was unimaginable when

I was growing up.

AMANPOUR: Did your parents ever become pleased, satisfied, accepting of you?

SOLOMON: My mother died a couple of years after I came out. So, we did not have very much time, but before she died, she said all the right things.

I’m not sure she meant them, but she said them.

AMANPOUR: That is good though.

SOLOMON: It was a good — yes.

AMANPOUR: Talk about that then. Because for parents who don’t know, and who are struggling, what should they do? I mean, obviously, we know what

they should do, but those who are really struggling, at least saying the right things, did it give you some comfort?

SOLOMON: It did give me comfort. And I think it made my father’s acceptance more possible. And he, in the end, threw us a beautiful wedding

and was very embracing.

AMANPOUR: Really?

SOLOMON: But I think parents really need to recognize that their children feel isolated and are suffering, even in situations where there appears to

be great acceptance. You have to understand that it’s difficult.

AMANPOUR: So, you mentioned many countries where it’s just, frankly, illegal and paying of death in many African countries, many Islamic

countries, and it’s terrible, and that happens now. But in the United States of America, so-called global superpower based on human rights and

universal rights, freedom of expression, freedom to be the individual.

We’re seeing right now today the very laws and norms and social acceptances that have come towards LGBTQ being challenged, whether it’s at the court

level or, let’s just say, the governor of Florida, or somebody who clearly wants to be the next president, has implemented a whole raft of strange,

strange requests, bills, laws. How do you see it going in Florida?

SOLOMON: There was a study that came out a few weeks ago that said that children growing up in States where gay marriage was legal, prior to

federal recognition, had significantly better mental health than children growing up in States where it was illegal. And I had, what was to me, a

shocking experience which is that I was giving a lecture on youth suicide that was sponsored by the largest children’s hospital in Northern Texas.

And I went down there and before I came, they said someone was going to interview me after the lecture, and they wanted to look over my notes

before I came down. And I said, well my notes won’t make that much sense to you. I said, but I’ll send you some of the anecdotes I’m going to tell.

AMANPOUR: Because you scribbled them? Yes.

SOLOMON: Exactly. And so, I sent them a few things and I got a message from the children’s hospital saying, one of the people you talked about is

transgender. And transgender children is a very politicized issue here, and we feel that you are talking about that will alienate a lot of people. So,

we would like to ask you to skip that story.

And I ended up giving the lecture, telling that story, and ending by saying that anyone who supported legislation like the legislation in Texas, that

takes medical decisions out of the hands of children, their doctors, and their parents, and puts it in the hands of people who have no

qualifications, thereby further stigmatizing —

AMANPOUR: Such as politicians?

SOLOMON: Exactly. Thereby further stigmatizing what is already the most marginalized group in America, that those people have blood dripping from

their hands. And it seems to me —

AMANPOUR: That is pretty harsh. Blood dripping from their hands.

SOLOMON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: What do you mean?

SOLOMON: Well, that the rate of suicide among trans children is the highest after children who were sexually abused in early childhood in the

nation. And if you said to me that a children’s hospital did not want to touch something that is killing a record-breaking number of children, what

kind of responsibility is that to the larger society?

And in the States, where there are these laws, and where trans children aren’t able to live as who they are, the rates of suicide among them are

incredibly high.

AMANPOUR: OK. I’m going to get that in a moment. But first, I want to ask you about youth suicide, young people suicide, which is as you say

exploding right off the record levels. So, you wrote a really powerful essay entitled, “The Mystifying Rise of Child Suicide”. I want you to just

read — we’ve given it to you, we’ve printed out a small extract from the article, and then we’ll talk about it.

SOLOMON: Children’s worlds may be smaller than adults, but their emotional horizons are just as wide. Because we find our own pain observed once it

relents, most of us don’t tell people when we’ve had a night of clawing at our inner selves.

AMANPOUR: And it’s very powerful and very poignant because your article is about a young child who actually commits suicide just before his 12th

birthday. He — you knew of him because he was at school for a period of time with your own son. What did you conclude happened there?

SOLOMON: What most struck me was that this was a child who had some struggles, whose parents were well-educated, well-connected, well-off. They

did everything they could for him. They were incredibly loving, attentive, dedicated, devoted parents, and they didn’t get the help that they needed.

Which is not to say that any help could necessarily have saved their son, but they struggled to find a way through.

And I thought if families like that are struggling, then what is happening to people in rural parts of the middle west? What’s happening to

impoverished immigrants living in the urban jungle? What’s happening to all of the people who don’t have that kind of access? And what I discovered

when I began doing my research is that the rate of child and youth suicide has escalated incredibly, dramatically, especially since 2012. It’s been

going up since the ’50s, but really since 2012.

AMANPOUR: Why?

SOLOMON: Well, I think it has a lot to do with social media and the spread of cell phones. I think it has to do with helicopter parenting and the way

that children end up feeling they are not confident to act and to live in the world. And I think it also has to do with the general pressures of

modern life in which the pressure to succeed is greater. In which circumstances are more crowded. I mean, I could list 50 reasons, but I

think those are the lead ones.

AMANPOUR: You’ve probably heard of the latest film that’s just come out called, “The Son”, it’s by Florian Zeller?, it stars Hugh Jackman as the

father of a young boy with clear mental health problems that nobody could figure out. Here is what Hugh Jackman told me about it when I asked him.

HUGH JACKMAN, ACTOR, “THE SON”: The story centers around a young man, 17- year-old, going through a severe mental health crisis. But actually, what we are doing is watching it and feeling this through the people around him.

His parents, the teachers, the people who are in contact, and how they deal with it and try to help.

Because I think we are living in a time where there is so much ignorance, and frankly shame, and embarrassment about the issue. We don’t know a lot.

We just feel unsure to talk about it. Somehow there is a feeling of shame. And that it’s something that as a parent, I should be able to fix. I should

be able to do.

AMANPOUR: Depression is often not recognized.

SOLOMON: Well, parents are often in denial, as I think the parents in “The Son” are and don’t see things because they are too painful to recognize.

But also, people are very good at keeping secrets. Children and young people keep secrets. I kept a secret that I was gay for years and years and

I thought I was incredibly close to my parents. We were incredibly close except that we never talked about the most significant thing about me.

And so, I think children who are depressed. Some of them are obviously going to pieces, and those, in many ways, are the ones who are easier to

help. It’s the ones who hide it who are so difficult. And at least half of youth suicides are committed by people who did not, in the past, give any

indication that they were struggling with mental illness.

AMANPOUR: Tell me if I’m getting this wrong. Did you have to go through conversion therapy?

SOLOMON: I put myself into a form of conversion therapy —

AMANPOUR: OK.

SOLOMON: — when I was about 17. I did something called sexual surrogacy therapy in which I went and met with women and there was a sort of

supervising man who called himself a doctor, and I had these sexual exercises. It was my attempt to become straight. And it rose out of a great

deal of self-hatred and a lack of self-acceptance. It wasn’t that my parents sent me there, but I thing the messages in my household were that

led me to go there.

AMANPOUR: And you suffered depression. Did your father help you? Did your parents help you get out of that depression? Your mother did die shortly

after you came out. Did your father help?

SOLOMON: My father helped enormously. He was a remarkable man. He died just in January of last year. And yes, it was a time when I wasn’t in a

relationship, and when many things in my life were very unstable and uncertain, and I ended up moving back in with him. Someone once said to me,

oh, your father really gave you a safety net. And I said, no. My father is actually on the trapeze with me. He wasn’t just giving me a safety net.

AMANPOUR: Well, isn’t that a nice way to put it, especially after all of that alienation that you went through together.

So, let’s fast forward a little bit to the actual current day, and that is the, you know, the political situation. There is a massive culture war

going on in the United States and in other democracies, actually. And it’s often around women, around the marginalized, around minorities, LGBTQ. And

we see from, you know, banning books on the issue to — what do they say in Florida? Don’t say gay —

SOLOMON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — or whatever. I mean, what effect, do you think, that will have? Do you think that will stick? Is it possible? I mean, you see a lot

of counterprotests. You saw the, you know, the votes in the midterm elections were around the idea of, you know, independents and human rights

frankly.

SOLOMON: Well, look, when the Supreme Court made its atrocious decision throwing out women’s right to reproductive choice, Clarence Thomas, in his

opinion, wrote that there should also be a re-examination of the right to gay marriage. The right to gay marriage is the most significant

breakthrough that we’ve had in many decades. There is an enormous backlash against us.

There is always a backlash against change and against difference, but there’s also been a great deal of cynical activity by politicians who use

these social issues as divisive measures in order to frighten the populace into voting for them. And distract by doing so from more basic issues of

freedom and economic justice and so on, that I think are really at the base of the problems in the U.S. and in much of the developed world.

AMANPOUR: It’s been said that, you know, when you start banning books, you start, you know, really clamping down on human rights, all the issues we’ve

just been talking about. Do you see a direct line from one to the other?

SOLOMON: Well, look, my book has now been banned in a number of school districts. And so, I —

AMANPOUR: In the United States?

SOLOMON: Yes. And so, I’ve experienced this. And people said to me when it happened, oh, it’s kind of a kick. You know, your book must really matter

if they’re bothering to ban them. And I thought it might be my attitude. It’s actually an incredibly upsetting and difficult experience to feel that

words that you wrote and invested to the best of your knowledge only with love, have been seen as so dangerous and so damaging that people shouldn’t

be exposed to them.

There is a real attempt in the United States, and I’m afraid there are elements of it from both the right and the left, to restrict open speech

and to restrict their sharing of knowledge and information and ideas. On social media, you mostly interact with people who agree with you because

that’s the way the algorithms work. And what it has done is to factionalize the country, and perhaps much of the world, to a point where people are

taking more and more extreme positions. And it’s not simply that they are unsympathetic to what the other side believes, it’s that they don’t

understand it and they don’t know where it came from.

And so, there is no point of contact and there is no effort for it or even grounds for compromise.

AMANPOUR: That is pretty dark. So, where do you see the light? I mean obviously, you know, human progress is always based on oppression and push

back.

SOLOMON: Right.

AMANPOUR: You know, resistance. So, in this regard, where do you see hope?

SOLOMON: There’s a lot of hope, I think, simply in the lives that people are leading. I mean, I feel like I would not probably have gotten married

and had children if it weren’t for the work of the activists who came before me, and the activists of my generation have done a lot, and there’s

a next generation coming up. I lecture sometimes in the LGBT program at the university where I studied in America. And —

AMANPOUR: Which is?

SOLOMON: Which is Yale. And when I go there, I say, you know, the program was set up by Larry Kramer, who was an important gay activist.

AMANPOUR: Oh, yes.

SOLOMON: And he talks about what it was like to be gay at Yale in the 1950s, and I think I would have died. And he indeed made a suicide attempt.

And I think I’m so lucky that I was there in the ’80s instead. And then I see the people who are there now and I feel so envious of them. And I

always say that my fondest hope is that someday they will come back and they will be as envious of the next generation as I am of them.

AMANPOUR: And, wow. And you think, you know, Larry Kramer got over that impulse and essentially lead America to change its HIV-AIDS policy and all

the rest of it. It does show, actually, what you can do.

SOLOMON: Yes. I think there is enormous room for progress. And I think there is great determination. And I think there is a very broad, general

population who are actually sympathetic to what are often couched as liberal causes. Most Americans, over a very short period of time, have gone

from disapproving of gay marriage to approving of it. The center is very movable in America. The noise comes from the edges, but the center tends to

shift toward justice.

AMANPOUR: And the center is also very much, you know — it’s very much sort of a fait accompli amongst young people. I mean, you talk to young

people about any of these issues and they are like, yes, and? Yes, this is normal.

So, does that give you some hope? You know, given that you study young people and their mental health and bullying and this and that. What is it

like for young people in schools these days if they are gay or?

SOLOMON: I had a nice moment of revelation where in the midst of the school’s application process for my son, for high school. And one of the

schools — as an essay question said, can you write about your identity and how your being at our school will enrich the diversity of identities at our

school?

And our son looked at us and her said, look, I’m a relatively, privileged, straight white boy from a private school. He said, I don’t know what to do

with this. And I said, well — I said, you can write about the fact that you are in a gay family. And he said, that’s not very interesting.

And I thought, you know, it wasn’t very long ago that that would have been so interesting, that there was nothing else to talk about.

AMANPOUR: That’s amazing. Andrew Solomon, thank you so much, ineed.

SOLOMON: Thank you. A pleasure.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now to another critical social issues in the U.S., racial justice. We’re going to look back at a case which helped spark the U.S.

civil rights movement and that was the lynching of Emmett Till. Our next guest is the last surviving eyewitness of that tragedy and details his

memories of it in a new book, “A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on the Journey to Justice for My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett Till.”

Reverend Wheeler Parker is a pastor, a district superintendent, and a public speaker. And he now joins Michel Martin.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Thanks, Christiane. Reverend Wheeler Parker Jr., thank you so much for talking with us today.

REV. WHEELER PARKER JR., COUSIN OF EMMETT TILL AND AUTHOR, “A FEW DAYS FULL OF TROUBLE”: My pleasure.

MARTIN: And I’m mindful that although you are being nice to us, it really isn’t your pleasure that you’ve lived with this very terrible story for so

many years and I can only imagine that every time you talk about it, it probably cost you something, doesn’t it?

PARKER: It does. It’s — but that’s a price, I guess, you pay to keep it out there and give him the respect and honor that he needs.

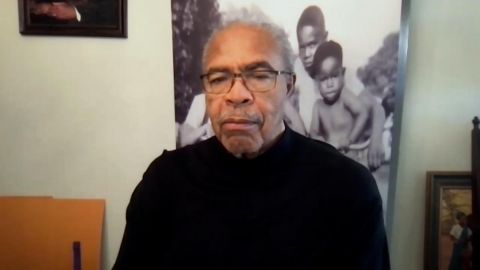

MARTIN: So, tell me about your cousin Emmett Till. And I see that there is a picture of you and him behind you.

PARKER: Uh-huh.

MARTIN: You’ve said many times that, you know, he was not just your cousin, he was your best friend.

PARKER: Yes.

MARTIN: Tell me a bit about him. What was he like?

PARKER: Fun. Never had a dull day in his life. Exciting. Always something going on. If you were around him, you knew that he started — I got to say,

he was the center of attraction all the time.

MARTIN: Fun loving kid.

PARKER: Yes.

MARTIN: Nice personality.

PARKER: Yes.

MARTIN: Nice smile.

PARKER: Uh-huh. Nice smile, yes. He had a beautiful smile.

MARTIN: You all were living in Chicago, Emmett and you and other family members like so many other African Americans had moved up from the south to

the north and the Midwest, and to some degree the west, in search of more, you know, opportunity. So why did you and your cousin happen to be back in

Mississippi that summer?

PARKER: I had been in Chicago/ Argo, Illinois since January 1947. And this is in — this is in the August of 1955. My grandfather had come to Chicago

for a funeral. And Emmett learned that I was going back with him, and he would not have it any other way, because he did not have any sisters or

brothers. So, in other words, they took me a long. So, we were, like, inseparable. And he insisted that he go back south with me, and they did

not think it was a good idea, but he insisted.

MARTIN: And why did they think it was a good idea?

PARKER: Because if you did not live in the south or experience it, you had no idea what it was like for a black male. And what they thought could

happen is exactly what happened.

MARTIN: You mean the sense of having everything about your life controlled —

PARKER: Uh-huh.

MARTIN: — by the need to defer to white people, I think, is that — that’s what you are referring to?

PARKER: You are putting it lightly, but yes. And they made sure that existed. A lot of people lost their life. And we were constant reminded

that you were inferior and they were superior. Constantly reminded. There would leave bodies lying here or there, or leave them hanging for a while

so that you get the message. And the message was well entrenched in our way of life.

We had to say we sent droves of children to the south every year. They — from the north and went, but they were still train and surreal and

entrenched in the ways of the south that we enjoyed ourselves immensely when we went down there.

MARTIN: You and your cousin were picking cotton during the day. Is that right?

PARKER: It was cotton picking time. And in the south, if you wandered around a town and it’s cotton picking time, you are going to end up in

prison and you’re going to stay there until cotton picking time is over. Everybody went to the field. Everybody went to the cotton field.

MARTIN: So, you would go and pick for half a day. And then what would you do, go have fun?

PARKER: Well, actually, we picked all day, really. The thing was from sun to sun. We just took off early that day to go have some refreshments at a

little country store three miles down the railroad.

PARKER: So, I was going to ask you that. So, how did you and Emmet, your cousin Emmett, whom you called Bobo, how did you wind up at the store that

day?

PARKER: Usually when you went south, and this was a norm, you are in the hands of an adult.

MARTIN: Uh-huh.

PARKER: And if you went to town or somewhere, there is an adult, always, to kind of correct you. But my grandfather was 67 years old. He had a son

named Maurice (ph), (INAUDIBLE), he had a car. And so, we were kind of on our own, which is a mistake. We just got there on a Sunday, and here it is

Wednesday, we are going to this little country store, and of course, that is where everything got started.

MARTIN: I cannot help but think that, you know, we’re asking you to remember the beginning of the worst day of your life.

PARKER: Uh-huh. Yes.

MARTIN: But if you would, just as briefly as you can, what happened?

PARKER: We got to the store and everyone was gathered around and laughing and talking. They were playing checkers and telling jokes. And Emmett love

jokes. He paid people to tell him jokes. And so, at the store, I decided to go in and purchase some things. But while I was in the store, I remember

Emmett coming in. In my formative years were spent in the south, I spent seven to eight years, so I was well entrenched in the ways. This is how you

were taught that from the day you could understand how to stay alive as a black boy in Mississippi.

So, I — so, I saw him coming and I said, man, I hope he — I remember my heart — I hope he’s got it together. That he got his language together,

like the yes sirs, and the no sirs, and the politeness that they demanded. And so, I said, I hope he got it together.

So, I left him in the store. And of course, shortly thereafter my Uncle Simeon came in, I was 12 and he 14 or 16, he came in with him and nothing

happened while I was in the store. They came out, nothing happened at all.

MARTIN: And then when did you realize that something was going on?

PARKER: Well, shortly after I left out, and then they came out, and then Mrs. Bryant (ph) came out. And coming out of the store, she turns to her

left, and as Emmett was, he loved to make people laugh, he gave the wolf whistle. There’s so many different stories told about that and where it

happened and all that, but he whistled at her, he did whistle at her, and when he did that we just could not believe in Mississippi in 1955 that he

whistled at this white lady, where people have been killed for raising their eyeballs that is looking at her. And no one said let’s go. My uncle,

16, driving the car. Everyone made a beeline for the car and we took off down this gravel road.

MARTIN: You knew right then that there was going to be trouble. So, what did you do then?

PARKER: Well, we got in the car, and now Emmett is a sight. He’s scared now because we are showing these emotions. So, my uncle sped down the road

and dust was flying everywhere, and there’s a car behind us. So, someone is like, they are after us. They are after us. And we knew rightly so that

they could be after us for what he has done.

So, we pulled to the side, jumps out of the car, ran through the cotton field, and the car goes right on by. And we were (INAUDIBLE) at the edge of

the road and Emmett asked us not to tell my grandfather. So, it’s a Wednesday. We did not tell my grandfather. Thursday passed. Friday passed.

Saturday passed. And we kind of forgot about it. We forgot about it. Otherwise, we should have probably been on a train heading back north, but

then they would come to the house sometimes, and someone would aggravate.

MARTIN: So, when someone finally did come to the house what happened then?

PARKER: It was Sunday morning. We had gone to town just prior to that — to Greenwood (ph). We got home, I guess, about 12:00. Not thinking

anything. We went to bed. I — it’s four big bedrooms. I’m in the bed with my Uncle Maurice. And then about 2:30 in the morning, I hear these people

talking, and they’re talking about what happened at the store. Being raised with very strong faith, first thing I said, when death is imminent, I said

God, we’re getting ready to die, these people are going to kill us. I’ve heard the stories and I know what they did and they had once killed.

And I’m shaking like a leaf on a tree. And the thing that I remember most is that not only am I getting ready to die, I’m 16 years old, my

relationship with God is not right. And when death is imminent, for some reason, you think about all the bad things that you’ve ever done.

So, I’m praying to God, not out loud, and saying, God, if you just let me live, I need to get right with you. If you just let me live, I’m going to

take care of that. I’m going to get that together.

MARTIN: Uh-huh.

PARKER: And literally shaking, and in walk these guys — dark as a thousand midnights, you can’t see your hand before your face, and no lights

on in the house. And they enter in with a flashlight in one hand and a pistol in the other. And I closed my eyes to be shot.

MARTIN: Uh-huh.

PARKER: I opened my eyes and they were passing by and they went to the next room. Emmett wasn’t there. They went to the third room, they found

Emmett in bed with my Uncle Simeon, and it was just pure hell in that house. It’s just unbelievable. The tension and the helplessness. That’s

what — I think that’s what resonates so strongly in a case like that, how helpless you are. You can’t call your grandfather because he’s in trouble

too. So, you just — being a people of faith, we just started praying and they left with Emmett, and that’s the last time we saw him alive.

MARTIN: Oh, my God. There’s just so many things going through my head right now. But your grandfather, the humiliation of not being able to

protect his grandson —

PARKER: Yes, yes.

MARTIN: — from people in his own house. And then —

PARKER: Yes, it’s the lowest of the low.

MARTIN: Uh-huh. When did you realize or when did you find out what had happened to Emmett?

PARKER: They started looking right away near the rivers and the bridges and — but they had said that if wasn’t the one, they’re going to bring him

back. And I left, of course, and we found — I found out on the police on Wednesday, when they found his body. By this time, I was back in Chicago.

MARTIN: They had spirited you out of town, basically, for your own safety, right?

PARKER: For sure. Right away.

MARTIN: Did you hear what had happened to Emmett? I mean, did you know at the time they found his body, as you said, days later. But the fact he had

been tortured, the fact that his body was destroyed? Did you know that then?

PARKER: No, we did not. We did not. We didn’t know the condition of the body. We didn’t know — only we knew is they had found him. And of course,

they got him back here to have his funeral here.

MARTIN: So, now many people know some of the outlines of the story from there, that the courage of his mother, Mamie Till, to have an open casket

funeral because she wanted the world to see what had been done to her son.

PARKER: Yes.

MARTIN: And many people know that, you know, two people were eventually tried in connection with Emmett’s torture and murder, but that they were

acquitted —

PARKER: Yes.

MARTIN: — by an all-white jury just, like, in a matter of, I don’t know – – what was it? You know, just actually like —

PARKER: 57 minutes.

MARTIN: Yes, minutes. I mean, if you’re being honest, did you believe that justice would ever take place? That someone would be held accountable for

what they did?

PARKER: No, but it — this incident brought about changes.

MARTIN: Uh-huh.

PARKER: I think this is probably the first time — not one of the first, not the first time. One of the few times that a white man had been charged

with doing something to a black. As a matter of fact, when they went to arrest these guys, they told them, that’s BS. I’m trying to protect the

southern way of life and you’re going to arrest me? They were highly insulted because if time had passed, nothing would have been done at all.

They would have been rewarded or at least thanked for what they were doing, helped keep the system in place.

The system was very, very strong, and it’s still strong. What they were protecting then, they protected now. Even still today, I see it in — the

young man that was choked to death up there in Minnesota. You see it — I see it all the time. First thing I think about is Emmett Till. The system

still prevails.

MARTIN: So, again, let’s sort of fast forward a bit. The two men who were responsible for torturing Emmett — for kidnapping Emmett and torturing

him, they had been acquitted at trial. But later on, in an interview with what was then, you know, a very prominent, you know, magazine, they

admitted, you know, what they have done. You know, what was that like for your family? I mean, did it feel at least there was an acknowledgment, or

just — did it make it even worse that there was no accountability?

PARKER: Well, living in a situation, in an environment, you are not surprised. Like I said, this is the first time, so we’re making progress.

We got a trial. That’s unheard of. And we didn’t expect anything to come out of it, or you’re say, well, maybe there’s a possibility. Maybe

something will be done and you’re thinking that, man, they arrested these guys and they had trial.

And of course, they admitted that they did it after the trial. We’re not surprised by that. And they were awarded, they were paid money, I

understand, for their story.

MARTIN: Uh-huh.

PARKER: Of course, the story was just so — it resonates with me now. It was so erroneous and so degrading that it bothers me even to this day. The

way that they portrayed Emmett to justify what they did to him.

MARTIN: And again, you know, fast forward even further into 2017, you know, a historian revealed that in interviews with Carolyn Bryant, who was

the young woman who accused Emmett, he revealed that Carolyn Bryant had lied and had acknowledged lying about her encounter with Emmett Till at the

store.

At a trial, she had this whole elaborate story about how he had allegedly attacked her, and had said several things to her, which you knew could not

be the case because, as you said, he had a very pronounced stutter. Did it make you feel, at least, a sense that the world knew what you knew, which

is that she had lied?

PARKER: You know, we were not privy to that story you just told —

MARTIN: Uh-huh.

PARKER: — until we found the transcript about 50 years later. We had never heard anything like that before. We were privy to her memoirs, and

she don’t remember him stuttering. That was his way of life. He did not talk without stuttering. So, the lie that she told still prevails. You got

to justify what they did to Emmett. So, they used those kinds of things to justify what they did to him.

MARTIN: You’ve just written a book called, “A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on a Journey to Justice for My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett

Till”. You co-wrote it with a longtime friend and co-author, Christopher Benson, who’s also a lawyer. Why was it important to you to write this book

now? Why this book and why now?

PARKER: I was very reluctant to write a book because so many stories had been told. And for 30 years, they never interviewed me. And so, I’ve been

hurt with the stories that have been told of what happened at the store. And I knew it wasn’t the truth. I felt that we were at such a disadvantage

competing with the major magazines and the articles that had been written.

So, I was just reluctant to write it. And then I decided — well, they convinced me that somebody will believe your story. So, here I am now

hoping someone will believe me because I was an eyewitness. Many stories have been told. Many things have been said. But we were eyewitnesses,

Simeon and I.

MARTIN: Before we let you go, how do you feel now that you got your story out? Now, that you’ve been able to tell your truth, how does it feel?

PARKER: It feels good because I — speaking in — people hear me and they believe it, you know. So, I don’t feel as helpless as I did from the

beginning, because I do have evidence (ph) to tell the stories like through your system and other systems. So, I feel good that I’m able to help shed

the light and get the story to the schools. So, I feel better about it now. But I’m still — at the end, I’m still thinking about how he died and the

price that he paid.

MELVIN: Reverend Wheeler Parker Jr., thank you so much for talking with us today.

PARKER: My pleasure, and look forward to meeting you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And finally, tomorrow is International Holocaust Remembrance Day, and we’ll be hearing from 99-year-old survivor Stella Levi, and the

author Michael Frank, who has put her remarkable story to paper. The book, “One Hundred Saturdays”, is the product of exactly that, six years of

conversation where Stella revisits her childhood among the Jewish community of Rhodes (ph), and surviving Auschwitz. Here’s a clip from the trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHAEL FRANK, AUTHOR, “ONE HUNDRED SATURDAYS”: One Saturday afternoon, seven years ago, I went to speak to a 92-year-old woman about her childhood

and youth on the Island of Rhodes, where she grew up in a storage, Sephardic Jewish community. That until 1944, when the entire community was

deported to Auschwitz, had lived on the island in relative peace for nearly half a millennia. Her name was Stella Levi, and I had no idea that this

would turn out to be the first of 100 Saturdays I would spend in her company.

STELLA LEVI, HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR: Michael

FRANK: Stella.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Tune in tomorrow night for that important conversation.

That’s it for now. Remember, you can always catch us online and on our podcast. Thanks for watching and goodbye from London.