Read Full Transcript EXPAND

BIANNA GOLODRYGA, HOST: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREA GONZALEZ NADER, ECUADORIAN VICE-PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: I love Ecuador deeply. I believe Ecuador is a paradise, and they’ve turned it into

hell.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: An exclusive interview with the running mate of Ecuador’s murdered presidential candidate. Her concerns for our country and for Latin

America’s future.

Then, my conversation with former Mexican foreign minister, Jorge Castaneda. Why he thinks the U.S. has been failing Latin democracies.

Also, ahead —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JON BATISTE, MUSICIAN, “WORLD MUSIC RADIO”: Sun and the stars, night and the day. All of the while I was calling your name.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: — Grammy award-winning musician Jon Batiste sits down with Michel Martin. They discuss his highly anticipated new album, “World Music

Radio.”

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

LUBAINA HIMID, TURNER PRIZE-WINNING ARTIST: I didn’t want to be the only black artist. There’s no joy in that.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: — as the trailblazing work of Lubaina Himid returns to the spotlight with two new shows, we look back at Christiane’s colorful

conversation with the celebrated artist.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Bianna Golodryga in New York, sitting in for Christiane Amanpour.

Once a peaceful paradise, famed as the gateway to the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador’s now drawing the global spotlight for a very different reason, as

it wrestles with a surge in violent crime. Three politicians have been assassinated there within the last month, with the murder of presidential

candidate, Fernando Villavicencio, shocking the world.

But this violent uptick isn’t limited to Ecuador, while drug cartels have long fueled brutality in nearby Mexico, the bloodshed is spreading all the

way south, impacting countries like Chile and Argentina. In an exclusive interview, Rafael Romo sat down with the former running mate of Ecuador’s

murdered presidential candidate. She told him how her life has been since that moment, and why she fears for the future of her country.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREA GONZALEZ NADER, ECUADORIAN VICE-PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: I think any other Ecuadorian is at the risk of getting shot right now in the street.

RAFAEL ROMO, CORRESPONDENT (voiceover): She was supposed to be there, as his running mate, Andrea Gonzalez Nader, should have been right next to

Ecuadorian presidential candidate, Fernando Villavicencio, when he was shot last Wednesday as he was leading a rally in Quito, the capital.

GONZALEZ NADER: Fernando was shot three times in the head.

ROMO: Has it sunk in that you could have died because you were supposed to be right next to Fernando that night when he was shot dead.

GONZALEZ NADER: Yes. Yes, I was supposed to be there next to him, getting inside the car that had no protection against bullets. And we wore no

bulletproof vest because we were trying to get the people this message that we had to be brave.

ROMO (voiceover): In an exclusive CNN interview at a location we’re not disclosing for her safety, Gonzales said Villavicencio’s murder is yet

another gruesome and shocking example of how fragile democracy is in Latin America as a region. But living in fear, she says, is not an option.

GONZALEZ NADER: I want to change this country. I want this country to be a place of peace, a productive country. We’re known around the world for our

incredible chocolate, our bananas, our shrimps, our coffee. I love Ecuador deeply. I believe Ecuador is a paradise, and they’ve turned it into hell.

ROMO (voiceover): Villavicencio was a 59-year-old lawmaker in the National Assembly known for being outspoken about corruption and violence caused by

drug trafficking in the country.

In May, he told CNN en Espanol that Ecuador had become a narco state. His political platform was centered on leading a fight against what he called

the political mafia.

GONZALEZ NADER: We knew it was — there was a high risk of him getting attacked by the same mafia and the same organized crime and the same

politicians that are linked with this organized international crime.

ROMO: After the assassination, current Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lazo declared a state of emergency for 60 days. On Saturday, 4,000 members of

the Ecuadorian police and military raided a notorious prison in Guayas province and transferred an alleged leader of a local drug gang to another

facility.

ROMO (voiceover): Gonzales says organized crime is a regional problem that requires a regional solution.

ROMO: How does Ecuador solve its security problem? Is it something that Ecuador can do by itself, or does it need help from the international

community?

GONZALEZ NADER: We need teamwork from international intelligence to find out how to stop this. Cocaine is done in Colombia and goes — gets through

Ecuador, through our coasts where it goes back to Mexico and then it’s delivered to the United States and Europe.

ROMO (voiceover): Ecuadorians go to the polls on August 20th for the first round of an election to choose a new president. But even something as

simple as voting is an act of courage in this country, and many may decide to stay home.

Rafael Romo, CNN, Quito, Ecuador.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: Well, for more on Ecuador and the wider picture in Latin America, I spoke with the former Mexican for minister, Jorge Castaneda. And

we discussed the violence, corruption and economic woes that are plaguing countries across the continent.

Mr. Foreign Minister, thank you so much for joining us today. Let’s start with the news out of Ecuador and that stunning assassination of

presidential candidate last week, Fernando Villavicencio, 10 days before the first round of elections.

As you know, his slogan for campaigning was, it’s time for the brave. Since then, six suspects were arrested, all foreign members of organized crime

organizations believed to be Colombians. His running mate said this to CNN, this is a disturbing moment for the whole region and eventually for the

world’s democracy. Do you agree with that statement? And what was your reaction to that stunning news of his assassination?

JORGE CASTANEDA, FORMER MEXICAN FOREIGN MINISTER: Well, I think she has a point, Bianna, in the sense that this is an important presidential election

that comes, by the way, in an unscheduled manner. Sitting President Lasso still had two years to serve, but decided legally, constitutionally, to

call for earlier elections and not run himself.

And so, this, in a presidential election, in a country in Latin America, that is a democracy and a functioning one, is a very alarming sign. And

it’s alarming also because it is clearly the penetration of electoral politics, of democratic rule by the cartels. We don’t know exactly yet and

we may never know, which cartels and exactly why. But it seems pretty clear that this assassination had something to do with organized crime, with the

drug trade, et cetera.

Ecuador has been plagued by this now for several years because it’s caught between Peru and Colombia, two most important cocaine producers. It is

sending drugs from Ecuador, either through Brazil to Europe or through the Galapagos Islands to Mexico, and then to the United States. This is a very

serious matter. I think Villavicencio’s running mate is quite right in being so worried.

GOLODRYGA: And you talk about Ecuador once being known as an island of peace. And as you said, we’ve seen a stark — a vast increase in violence

and crime in that country. Let me just give you some statistics. The homicide rate in Ecuador has risen from five for 100,000 inhabitants in

2016 to 25 per 100,000 last year.

CASTANEDA: That’s right.

GOLODRYGA: What is the root cause of this spike in crime, specifically as it relates to these drug cartels?

CASTANEDA: Well, it has — it’s different in each country. The case of Ecuador, Columbia and up to a point, Peru, is much more linked to cocaine,

which is the traditional drug produced in those countries and shipped now – – the last few years through Ecuador. The case of Mexico with fentanyl, which is a different — has a different business model and also leads to

high degrees of violence.

Mexico’s homicide rate is around 25 per 100,000, that is about the same as Ecuador’s except that we’ve had that rate for several years now in Mexico.

So, yes, there is an issue of the enormous power and the internationalization of the cartels throughout South America. You have

countries even like Chile and Argentina traditionally very peaceful, very nonviolence countries, with very low levels of homicide per 100,000

inhabitants, where people now are worried or even alarmed by the degree of violence.

It’s still much lower than in Ecuador, than in Mexico, than in Columbia but it is changing. And this has largely to do with the internationalization of

the drug trade and of the international cartels. Whether they were originally rooted in Mexico or in Columbia, now they are everywhere. They

are like transnational corporations. Who exactly do they belong to? Who — where do they come from? We don’t know anymore. It’s like the big, large,

multinational corporations.

GOLODRYGA: What are some of the solutions you think are most effective here in addressing this issue?

CASTANEDA: Well, there are different solutions, I think, for different countries. In the case of Ecuador, clearly, they have to find some kind of

agreement or negotiation with their two neighbors, the Peruvians and the Colombians, so that the three governments are able to no longer use Ecuador

as a platform, and also for Ecuador to have a stronger police force that is able to let it cope with the size, the magnitude of the cartels that are

now operating in that small country and — that were not operating there before. For them, this is a relatively new phenomenon, five or six years

back. They’re obviously not prepared to deal with this.

In the case of other countries, there is a real issue, Bianna, about whether the war on drugs has been successful. And most people at this stage

believe it has been a failure. It’s been going on for more than 50 years, since President Nixon in the United States declared the war on drugs in

1971, and it’s obviously a failure.

More people are dying of opioid overdoses in the United States than ever before, after more than 50 years of the war on drugs waged largely outside

the United States, but at the urging of the United States, in Mexico, in Columbia, in Peru, in Bolivia, now the case of Ecuador. It’s a very complex

problem. But clearly, the war on drugs has failed.

So, then the question is, what is an alternative to the war on drugs? One clearly is legalization or decriminalization, because otherwise this will

continue. Another alternative is much greater international cooperation. And a third one is that the United States deal with the consumption issue

domestically, because at the end of the day, that’s what drives all of this, the enormous U.S. market for drugs.

GOLODRYGA: You’re right. And this is a crisis that’s only exacerbated here in the United States. Let me turn to Guatemala and their critical election

as well. On Sunday, we will see a runoff between the former first lady versus the son of a former president. This election has been plagued by

allegations of corruption, as well, and interference and concerns about the democracy in that country moving forward. Why is this such an important

election and what will you be watching for?

CASTANEDA: Well, it’s important because, really, for the first time in many, many years, it would seem that the more progressive candidate,

Bernardo Arevalo, who is the son of democratic president, going back to the 1940s and early 1950s, has a chance of winning. This is a country where

most of the presidents who have been elected over the last 30 years have ended up being as corrupt and as in the hands of the cartels and the army,

one after the other.

Arevalo seems to be a different type of person, which is why there have been so many attempts to derail his candidacy, to stop him from running,

then to stop him from moving on to the runoff. And now, perhaps, between now and Sunday — or after Sunday, to stop him from winning. He really does

represent an interesting challenging alternative to the status quo in Guatemala.

And Guatemala is a very important country, for many reasons, to begin with, because it’s the gateway to Mexico. For migrants coming all through Mexico,

to the United States, from the rest of Central America, from Cuba, from Ecuador, where tens of thousands of migrants have left over the past few

years, coming to Mexico and then on through the United States, Guatemala is key in the whole migration equation because it’s right on the border with

Mexico.

And secondly, because the tradition of corruption and military involvement done by the cartels in Guatemala, the elections are so important that we

can’t be sure that even if Arevalo wins that he’ll actually be elected to become the next president of Guatemala.

GOLODRYGA: Yes. It’s interesting, obviously, we’ll be paying close attention to Guatemala, but it’s interesting overall, we’ve seen this trend

in Latin American countries, this election of left-wing governments, and that includes Brazil, Chile, and Columbia. And then, there was this

surprise out of Argentina over the weekend where the far-right libertarian economist, people compare and even to Donald Trump of Argentina, Javier

Milei, won the presidential primary. And it comes at a time when consistently, now, we see that country plagued with economic challenges,

inflation as well over 100 percent, I believe Argentina is IMF’s — the IMF’s largest debtor.

What do you make of this surprise of the primary? And what do we know about this particular candidate?

CASTANEDA: Well, the polls got it wrong, as they’ve gotten it wrong in many places in Latin America, and elsewhere, by the way, in recent times.

He was expected to get about 20 percent of the vote, he got 30. He came in first in these primaries. But he is not necessarily the favored candidate

to win the presidential election in October, with the possible runoff in November, because the other candidate who will probably be running against

him, the main candidate, Patricia Bullrich, from the center right, probably has a greater chance of winning.

But clearly, this was a reaction against the incumbent government, the Peronist government, but also, against the Argentine political elite or

Kast, as Milei calls it, that have driven the country into the ground. But not now or the last hundred years or so with one economic crisis after

another, with inflation now running, as you say, over 100 percent yearly with devaluation of the dollar being a daily occurrence.

Argentines are fed up. And they seem to have bought on through Milei’s rather eccentric ideas, ranging from dollarizing the economy completely,

like Ecuador or El Salvador or Panama, but too much smaller countries, like eliminating or burning down, he says, the Central Bank, or even creating a

market for organ donors or organ sellers, which is somewhat extreme proposal, judged by any standard. I think it’s more a reaction against the

incumbent government and the previous one, people are fed up.

GOLODRYGA: Yes. And they’ve been plagued with economic challenges, as you said, for decades. Let me ask you the broader picture about the United

States’ relationship with Latin America. In 2020, you wrote an opinion piece for “The New York Times” in addressing what you said could be some of

this administration, the Biden administration’s, outcomes in terms of focusing on Latin America. You wrote, Biden can inspire Latin America, a

domestic transformation of the United States would have a tremendous impact in the region.

Three years later, as we’re approaching another presidential election here in the United States, did you see that happening and coming to fruition?

How would you rate the Biden administration’s approach to the region?

CASTANEDA: Well, I think it has been a bit disappointing, not necessarily and only for its own fault. I think that when the Biden administration was

unable to push through Congress its entire program this idea of a sort of new American welfare state that president Biden was not able to get through

Congress, he’s got a lot of things through Congress but not everything. The inspirational aspect that the United States could have had, the

inspirational effects that it could have had in Latin America didn’t happen.

Now, policy wise, there have been several problems. There’s been a lot of continuity with the Trump administration, unfortunately, on major issues

such as migration, such as drugs, the Biden administration’s policy toward Latin America has not been that different.

And perhaps more importantly, with the exception of Brazil, the United States has not been a force for strengthening democracy in Latin America at

a time when it is being weakened by all of these events that we have just been speaking about.

In the cast of Brazel, yes, the United States convinced, persuaded the Brazilian military to not pursue a military coup against President Lula,

who was elected late last year and who took office on January 1st, and was almost deposed in a coup with great military participation on January 8th.

The U.S. played an important role in having that to not be successful.

But in the case of Mexico, in the case of El Salvador, in the case of other countries, the United States is not being a forceful presence for — in

strengthening democracy in Latin America. President Biden is very concerned about democracy in other areas of the world, but not so much in Latin

America. Because he has to deal with migration and has to deal with drugs. But he is dealing with them in a very traditional way, which has proved to

be a failure.

GOLODRYGA: Jorge Castaneda, thank you so much for your time and analysis. We really appreciate it.

CASTANEDA: Thank you, Bianna.

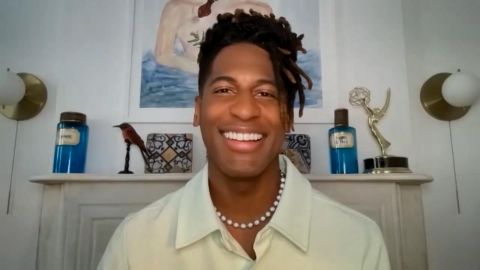

GOLODRYGA: Now, to a musical genius challenging genres. Jon Batiste has been busy. After winning five Grammys at last year’s awards, including

Album of the Year, he is back with a new record called “World Music Radio.”

The concept album weaves his signature style of jazz, funk and soul with global artists Lana Del Rey, Lil Wayne, and K-pop girl group, NewJeans.

Here is a taste of the single, “Calling Your Name.”

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JON BATISTE, MUSICIAN, “WORLD MUSIC RADIO”: Sun and the stars, night and the day. All of the while I was calling your name. I would get so lost in

my feelings, head in the clouds. I would get so caught up in believing something about. But you feel so good in my spirit, it’s all over me now.

No, I can’t go back no more

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: To break down this wonderful album, Jon talks to Michel Martin.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Thanks, Bianna. Jon Batiste, welcome. Thank you for joining us once again.

JON BATISTE, MUSICIAN, “WORLD MUSIC RADIO”: Yes, indeed. Hello.

MARTIN: It’s always a good day when we see Jon Batiste.

BATISTE: Likewise. I’m so glad to be back.

MARTIN: Well, before we talk about the new album, I mean, what a year. You were nominated for 11 Grammys, you won five. And this is on top of having

won an Oscar. How do you take it all in?

BATISTE: I just — I love the ability to create. And I put so much pressure on myself in the creative process that once I’m done with the

project, I’m spent. I’m totally —

MARTIN: Yes.

BATISTE: I’ve given it my all. So, I — it’s hard to think about my reaction until many years later, because I to process the creative part,

and then all that comes after it, the awards, the performances, the different things that I hear from folks who have invited the art into their

lives. And it really does take me a few years to process things.

MARTIN: The new album, “World Music Radio.” It’s crazy. It’s crazy. I just — it really does feel like a journey, right? It feels like a trip. First

of all, “World Music Radio,” why that?

BATISTE: Well, you know, it started as a prompt, world music and popular music. You know, if you look at pop music you look at world music, it feels

that in the last 10 years or more they’ve become more and more synonymous with each other. And the concept of world music as a genre is a horrendous

— it’s an atrocious genre, conception.

It’s really so marginalizing to cultures outside of America and Europe. It puts them all — all of the cultures outside of America and Europe bunched

together as one and it’s call world music, like it’s completely otherized.

So, I thought, well, wouldn’t it be an interesting prompt to reimagine what that could mean in the popular music context and use that as something that

we can expand popular music thinking about. So, I thought, wow, look at all the great music that’s coming out of the continent of Africa. If you go to

Asia, you’ll see all the incredible artists that have come — Latin America, South America, all the incredible artist in the popular cultural

space, that would be interesting.

It didn’t turn into “World Music Radio” until the latest stages of the creative process, like maybe nine months into the process before I was

done. I had the epiphany that it was a concept album. That it was an album where you lived through it by a character that I play. I’m the alter-ego of

Jon Batiste. There’s this character named Billy Bob Bo Bob who was is a DJ, who is an interstellar real, who is a — he’s like an all-knowing being

that somehow, down home, and very charming in this way that he guides you through the album.

So, all of this happened maybe a month before we were done. So, that is how we got to “World Music Radio.”

MARTIN: So, talking about the music again. It has so many interesting flavors and kind of nuances. And also, really famous collaborators, you

know, something that, you know, we haven’t necessarily seen with you before. I mean, obviously, when you were the band leader for “The Late

Show,” you had a number of great artists come in and sometimes they’ve sit in with you.

But this idea of collaborating with some of these really big names, you know, Lana Del Rey and then Lil Wayne, how did that ideal come to you?

BATISTE: Well, I thought about it from the perspective of casting a movie. And the album is so much like a movie. It’s really like you are watching a

film. You’re listening to it and you’re watching the film in your mind’s eye, and it’s really all these moments that happened and all the symbolism

in the album with certain characters and certain elements. Water is a symbol in the album. Butterfly is a symbol in the album.

So, I thought about all these moments that, in the sequence needed someone to step forward, another character, another voice. And it just happened to

be, wow, you know, this is best for Kenny G. to do, and this is Lil Wayne and, you know, this is NewJeans. This is — it created a tapestry that was

very diverse.

MARTIN: We talked earlier about how marginalized and your otherizing like the whole idea of world music can be. It’s like there’s — we get to be

here in the West, like — or in the United States, let’s say, or the U.K., we get to be pop and jazz and classical, but everybody else gets to be

world.

BATISTE: Yes. Like that’s the rest of the world’s music.

MARTIN: That’s — yes. That’s the rest of them. That’s them. But you — and you are including songs and languages that perhaps are not as familiar

to people. And I was thinking here about “My Heart,” where you feature a Catalonian singer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

BATISTE: There’s another thing that I think is really interesting with music and languages, and the idea that you can have a song or you can have

a popular music album that exist in more languages than just one. And, you know, I think that it’s an amazing opportunity to think about expression

and the use of language as a part of your expression in the popular music sphere.

The idea that “My Heart,” you know, I can sing in Spanish or even in the Catalonian dialect of Spanish to create this emotion. It heightens the

emotion. Rita Payez is an incredible artist who, you know, we were able to — you know, I didn’t know her. I discovered her online. She’s an unsigned

artist who plays the trombone and sings on this song.

And she’s an incredible artist that it moved me to the point that I wanted to step into that space to represent the emotion of the song we

collaborated on. And that’s the kind of thing that — you know, there’s so many possibilities there. And on the album, you hear different languages

throughout. But that one in particular, I’m very proud of how it really heightened the stakes of what we were doing.

MARTIN: Tell me more about “Master Power.”

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BATISTE: In their grimy hour, there’s a master power.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MARTIN: It’s kind of got a country feel, but it has prayer, intonations. Tell a little more about that. I heard some kind of Muslim call to prayer

intonations. Do you want to talk a little about it?

BATISTE: Yes, yes. There is a lot of sort of (ph) radical choices on this album. So, I’d never heard that before. I never experienced it, but I

thought there was such a common thread between the call to prayer and the different songs that you may here, the cantor sing in the Jewish tradition

or you would hear in the country music tradition where there’s gospel songs and southern country songs or, you know, Johnny Cash, southern shuffles,

and that kind of sound. And I never heard them put together.

And I also had never heard sampling done in a way where it’s not such an overt texture in the music, but it’s something that blends almost with the

instrumentation but kind of juxtaposes all of these different forms of worship, acknowledgment of the master power, the ultimate — the master of

the universe in that kind of creative — it created a milieu that speaks to that but from these really unexpected pairings.

MARTIN: One of the messages, if I can put it that way, of the album is kind of unity togetherness and stop hating. You know, basically, just let’s

enjoy and appreciate each other. In fact, like in the “Master Power,” you say, I love you if — even if I don’t know you, you know? And then, in

another track you say, love black folks and white folks, my Asians, my Africans, my Afro, Eurasian, Republican or Democrat. It’s one of the tracks

that’s gotten a lot of attention so far.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MARTIN: Is there anything about that that scares you or that you feel won’t be well received?

BATISTE: No. I think that, ultimately, there’s an interesting thing that happens when you’re truly yourself. And there is an authenticity that

resonates with people, right? It’s something that connects with people. And people want to know your heart.

Ultimately, we’re dealing with issues where the things that divide us are mostly rooted in a belief that the person on the other side doesn’t care if

we live or die. And how do you resolve anything if you are framing the conversation debate in that way? The context of having radical love is not

one of agreeing or even one of accepting the things that are atrocities to your humanity and the humanity of others. It’s not a way of marginalizing

any group either.

I think that the idea of what frames the conversations and how we have productive conversations and how we ultimately mobilize and how we live in

a space that is a form of activism but also a form of humanity, that’s the question that I would like to address through my art, in an abstract way,

and through my life, in a very real deliberate way.

MARTIN: You know people say it’s kind of a cliche, but it also happens to be true that music is a universal language. Do you have sort of a vision

for what you hope your music will do?

BATISTE: God is love. Yes, indeed. I have a vision for my music and what I hope it will do. But ultimately, I think the music that any artist makes

belongs to the public, once it’s released, once it’s a part of their lives and it’s a part of what they do. I just hope my music always leads to love

and always leads to people having a deeper sense of humanity, a deeper sense of insight, a deeper sense of what it means to be alive and

appreciation for what that is.

And I think that that’s in the frequency of the music. It reaches people in a way where you don’t need words and I don’t need to prescribe what I want

the music to be in their lives. It grows into — it walks into that. It’s almost like faith.

MARTIN: You are classically-trained. You know, you’ve worked across categories. You know, Duke Ellington’s highest compliment was to say to

someone that they were beyond category, right? And I think you’ve striven to be, you know, beyond category. But do you have a hope them? I mean,

especially collaborating with some of these pop artists that perhaps you’ll reach an audience that had not been exposed to you before?

BATISTE: I just think that with this album, it should be in the conversation of popular music in the same way, you know, we talk about

anybody who is in the top 10 of the charts. I see this album as being in that conversation, certainly.

Whether it reaches that point or not is not a success or failure of the album. But for me, this is an album that is geared reaching the widest

range of people without compromising any of my artistry and who I am. And thus, further expanding what can be placed in the popular music category.

Now, for me to do that and to not compromise is the achievement. Because the achievement of doing that as an artist takes so many years of knowing

thy self and knowing who you want to be as an artist, to be able to find a way to sculpt something that is uncompromising yet addresses the time that

you’re in and the culture that you’re in. It’s such a painstaking process with so much that you have to really think about to execute on that.

So, I’m proud of that, in and of itself, as an achievement. Even if I’m the only person who listens to it. Maybe that’s not healthy or what the label

wants me to say, but it’s the truth. But ultimately, it is in the conversation with the — you know, The Weeknds or the Taylor Swifts of the

world or whoever it is that you want to talk about.

And I also think that, not only that, I’m excited to tour this album because, believe it or not, you know, I was seven years as a student at

Juilliard for the age of 17, then a couple years where I was building the band, Stay Human, and then, we were on television for seven years with Stay

Human. And just last year is the first time I’ve ever created an album without this sort of occupational duress of doing many other things at

once. And I’ve never toured. This will be the first time I’ve toured.

And there’s so many people who, around the world, I want to go out and meet and see and be in person with and share this music with from the stage and

in the communities that have supported me all these years. So, the biggest marker of success will be, how many places in the world can I bring this

“World Music Radio” show to?

MARTIN: Well, before we let you go and, you know, you don’t have to talk about this if you don’t want to, but it has become known that your long-

term partner, now your wife, has been battling for years with a serious health condition. And you’ve been by her side, you know, for all of it, as

she has been by your side through your journey.

And I do find myself kind of wondering if being so close to something so hard has affected your art in this way as well? You are sense of, you know,

at the core, we really are just trying to stay human, you know, as your band title would say. And I just wondered if that proximity to such a

difficult journey has influenced this work and this album in particular?

BATISTE: For sure. There’s a song — the song “Butterfly” on the album is written specifically with that in mind. But in general, overall, I’ve

changed as a person in my approach to life. And ultimately, my approach to creating, which is, you know, you can’t have the person who is your person

so close to the veil and not be changed from that experience.

So, the way that it’s changed me is something I’m still processing. But I know for certain that it’s made me more fearless. And I already thought I

was fearless, but, you know, I just want to give the audience the best quality art that I can create and I also want to do it where I’m not

compromising myself and I’m not doing anything that is out of integrity, because we only have a show awhile (ph) and we represent not just ourselves

but all of the people we love and who love us.

You know, we can’t be messing around out here. And that’s a message for anybody out there. Do your thing. You know, you got it. Don’t hold it. And

don’t make yourself — your frequency dim for any reason, you know. Just, fearless. Pursue.

MARTIN: Jon Batiste, thank you so much for talking with us once again. It’s always a joy.

BATISTE: Yes, indeed.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: A celebration next of the British artist, Lubaina Himid. She was the first black woman to win the prestigious Turner Prize in 2017. Her

latest exhibition, “What Does Love Sound Like?”, is a famed Opera Festival in Glyndebourne. It is one of two new shows she’s opening this year.

Christiane sat down with the influential artist for her biggest ever exhibition at London’s Tate Modern back in 2021.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Lubaina Himid, welcome to the program.

LUBAINA HIMID, TURNER PRIZE-WINNING ARTIST: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So, this is not even a retrospective, because there are special pieces done for this fantastic exhibition. You walk in, and it is stunning,

the riot of color, the cacophony of sound. It’s a very different kind of exhibition than I have ever seen. What are you trying to say and achieve?

HIMID: Well, I suppose the most important thing I’m trying to say is that the audience member is the most important person in that room. Yes, I made

the paintings, but they are conversations with audiences. So, I want you to go in that room and understand that you have agency.

AMANPOUR: Meaning what exactly? What should an audience do to embrace the invitation that you’re offering them?

HIMID: Well, rather than look at the work and admire it, as you sometimes do in an art exhibition, you go in the room and ask yourself what this

reminds you of, what it makes you want to do, those sorts of questions around. Not so much, why is she doing this thing, but how can I enter into

this scenario?

AMANPOUR: I read that you said that art is all well and good, but it’s not as if what you’re painting exists in a silent vacuum. The boat, you’ll hear

the oars, you’ll hear the sea. So, sound is incredibly important for you as the life force around you.

HIMID: It is. I mean, it’s around us all the time. We’re walking down the street, we’re hearing all kinds of different sounds, different voices,

different music. And it doesn’t — it seems to me there’s an exhibition, why would it be different than that?

And a lot of the time, I want the sound that’s coming out into the gallery to encourage you to listen to the conversations you’re having in your head.

So, there’s a sort of three-way thing going on. Even the sound is trying to encourage you to feel and think about yourself and your actions and your

memories.

AMANPOUR: You were the oldest and the first black female artist to win the Turner Prize in 2017. How has that changed the way you work or the way your

work is received?

HIMID: Well, in a way, it hasn’t changed the way I work. But I suppose it did make me more daring. I guess I won the prize when I was 63. And I kind

of knew that they were not 63 years in front of me, knowing they were 63 years behind me. So, I absolutely understood that I have to make the most

of the years ahead. So, take any risks I could and keep going really. So, that made a difference.

There’s sort of no room for pondering, resting. I just want to make things, try things, work with other people and see what happens.

AMANPOUR: So, I want to talk to you about your work, a very — A Fashionable Marriage.

HIMID: OK.

AMANPOUR: So, that’s cutouts.

HIMID: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And what year was it done?

HIMID: Originally, I mean, I — this happens to me, because such a long time ago, but in 1987.

AMANPOUR: OK.

HIMID: Yes.

AMANPOUR: So, you were daring in 1987. It didn’t take you the Turner Prize to be daring, because this is a really political piece. You have Ronald

Reagan, and this was in the ’80s, when the whole idea of nuclear Armageddon was terrifying the world. You have Margaret Thatcher, who was prime

minister at the time.

What are you saying? Because I understood that there was a lot of backlash. In fact, you left London.

HIMID: I did. Well, what it was saying — I mean, basically what it was saying was that the art world is exactly the same as this political world.

Don’t kid yourself in museums or art galleries that you’re special and liberal, because, to us black artists, you’re behaving in exactly the same

way, ignoring us, doing damage to us, and not being interested in the — in any of the things we’re saying. And that was a pretty difficult thing for

people to hear. And, yes, a lot of people didn’t like it.

AMANPOUR: What did they say?

HIMID: Oh, well, I suppose art world people at the time, critics, curators, thought that they were being supportive. But they were being, you

know, patronizing and giving us tiny crumbs. And I guess, at the time, I was in my early 30s, I expected more, I wanted more. And I was more

ambitious for all of us. And I wanted to make a difference. And I had the nerve to be that bold. And I didn’t care.

But, yes — but I did think, oh, I will just leave because I can’t be bothered with this argument. I just want to keep making more art.

AMANPOUR: So, you left and you went to Northern England.

HIMID: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: But here we are. You’re back in a big way.

HIMID: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean, you’re having the last laugh, right?

HIMID: I hope so.

AMANPOUR: The Marriage work also took a little bit from the painter Hogarth —

HIMID: Yes, absolutely.

AMANPOUR: — who is currently, right now, on exhibition at the other Tate, Tate Britain.

HIMID: There’s a painting in the series Fashionable Marriage, it’s the Countess’s Morning Levee. And I have really copied it person for person and

translated it into the 1980s.

AMANPOUR: Why?

HIMID: Well, Hogarth was laughing at everybody, vicious to everybody, a bit of a bitter man, I suppose, but really interested in exposing political

hypocrisy.

AMANPOUR: You’re not — at least it doesn’t come across in your paintings — as a bitter woman, a bitter or sarcastic, devastating kind of artists,

because your paintings seemed to be full of joy. And even though you’re taking on very difficult subjects, you’re not, for instance, in — is it

called Le Rodeur: Exchange?

HIMID: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You don’t paint the victims of that event. You paint something very different. Tell me about Le Rodeur and how you decided to portray it.

HIMID: OK. Well, I suppose I wanted to examine what — first of all, what terrifies me as an artist, and that would be losing my sight. What would

terrify an art audience? Losing their sight, because they obviously adore looking at visual things. So, that is lurking there in this scenario.

The story of Le Rodeur is, it was a French slave ship that took captured Africans from the West Coast of Africa on the way to the Caribbean. And in

that horrific journey, many, many, many of the crew and all of the captured Africans lost their sight. So — sorry.

AMANPOUR: It was — no, no — a virus or what happened?

HIMID: Yes, an eye infection. It ravaged through the entire, I suppose, cargo immediately. And this seemed to me to be absolutely horrific and

terrifying. And — but what I’m trying to say in these paintings is that the vibrations, the traces, the dust, the heat of that still surrounds us.

So, those people in that room with the sea outside looking elegant but disconnected, they’re kind of feeling that true story, understanding that

they don’t feel quite right because they are the descendants of some of the survivors of that.

You know, when they reached the Caribbean, OK, you have done that journey. Goodness knows how. You have gone blind, you have survived it, and then

you’re a slave. It seems to me horror upon horror. So, there’s no point in painting that, because you or I would come into that gallery and be

horrified and overwhelmed by that.

AMANPOUR: One thing you just said is quite stunning. You said, those who survived, if they hadn’t been thrown overboard. The others were thrown

overboard?

HIMID: Yes, that happened a lot. Sometimes, the ship’s captain would feel that maybe the freshwater supply was low. So, rather than endanger his

crew, he would throw captured Africans overboard to, you know, save the water supply. That was what was written down. But I think that many

historians feel that, if there was any sign of insurrection, any sign of —

AMANPOUR: Disease?

HIMID: Yes. Then, let’s trap them overboard. But, of course, that was kind of dangerous because they were worth a lot of money. So, the insurance

claim found a lot of these things out, because, of course, everything is accounted for.

AMANPOUR: You’re from Zanzibar. Your father was from Zanzibar. And your quote was saying, you know, I was born into tragedy. I’m paraphrasing but,

my birth also, was tragedy. That’s because your father passed away very early.

HIMID: Yes. I was four months old. And my father who got malaria every year in that kind of way, that you can and you do and you get it every year

and, you know, you have a — you feel better and then, you’re OK again. And that particular year, when I was four months old, he got it particularly

badly and died.

And my English mother, if she had the choice, she could have stayed there with me. She could have left me there with my African family or she could

bring me to England, and she decided that’s what she wanted to do.

AMANPOUR: When you look back, was coming here to the U.K., did it provide you with a land of opportunity and would it have been different had you

stayed in Africa? Would you have been this artist? When you think back?

HIMID: I think if I stayed, I probably would have ended up designing kangas. I suspect, I still feel —

AMANPOUR: Kangas?

HIMID: The African cloths that I use a lot in my paintings to talk about conversations between women, really. I think I would have ended up being a

textile designer like my mother but in a bit in that kind of context. I suspect like in every young person’s life, there’s encouragement to be a

doctor or a lawyer, but I don’t think that would have happened to me.

AMANPOUR: You do paint on sort of a lot of different surfaces.

HIMID: Yes.

AMANPOUR: It’s not just canvas, right? I notice you have these lovely series of paintings. Man in a drawer. And there are different draws.

There’s the shirt drawn. Pencil draw. And it’s just fabulous. It’s just beautiful. What inspires you? Also, you paint on, what looks like old farm

carts.

HIMID: Yes.

AMANPOUR: What inspires you to just change your canvas or your — yes?

HIMID: Well, I’m really interested in having conversations with people but within an everyday sort of setting, if you like. So, a canvas is one thing.

It’s kind of recognizable as something that you would see in a gallery that is art.

But, you know, if you buy an old piece of furniture or just a secondhand piece of furniture, it doesn’t have to be, you know, antique or anything,

and you open a drawer, then there’s sort of the dust comes out or you somehow feel a trace of someone there before, a little piece of paper or an

ink stain in the drawer and you know that someone else has experienced that piece of furniture, has kind of — has owned it and loved it perhaps and

kept all sorts of precious things in there or just their socks or whatever.

And so, yes, I’m trying to do sort of two or three things at once, bringing audience member close, get you to remember when you bought that funny old

rickety chest or drawers, you opened it and there was a letter inside, there’s something magical about it but something that reminds you that all

around us is history and other people’s lives.

AMANPOUR: You’ve also, said, I obviously knew that there were black artists and black people who could do great creative things, but we never

saw it. We never saw representations in our contemporary world, in museums and elsewhere.

How much of an impetus was that for you and how do you feel now, when we see many, many black artists being recognized, being exhibited, being

awarded?

HIMID: Well, I mean, it was huge impetus. I mean, obviously, I did — well, I suppose one of the things that I always thought and always said

when I was much younger is that, I didn’t want to be the only black artist. There’s no joy in that. One wants to have conversations as part of a

community of people.

And I would go to the houses of people that I knew and there were prints on the wall done by African artists and they weren’t famous or lorded, but

they were things that people had bought and bought straight from the artist. My mother had things that were different sorts of embroidered

things or printed things or painted things. So, I knew that, you know, African people were making things.

And — but it was very difficult to communicate that with the people that, if you like, held the key to showing it widely. So, we did it in places

that weren’t galleries, first of all. We thought, OK, we are making this work and we want to show it in a nice setting, you know, to our families,

to the people we know that we work with.

So — and I think what’s changed is that many, many more people had the courage to keep going, the energy to keep going. And there was a lot of

encouragement, perhaps on a small scale, say in Britain from regional galleries, in the states from smaller galleries, from collectors and

teachers. And gradually, over these 40 years, there has been this sort of understanding that we are not threatening something, threatening to destroy

something, but just saying, we are enriching. That’s the point, we’re enriching the culture. And showing that we have a contribution to make.

AMANPOUR: What about being female? I’m going to read you — and you probably seen it, everybody’s seen. It’s in this museum by the Guerrilla

Girls.

HIMID: OK.

AMANPOUR: And the legend is, do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum? They’re basically saying, less than 3 percent of artists in the

modern art section, this is the Met in New York —

HIMID: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — are women. But 83 percent of the nudes are female. Now, yes, this was done in 1989. And no doubt, the statistics and the facts have

changed. But the point is the same, right? The point is how women are represented.

HIMID: Yes. And I think it’s a really difficult one because that should have been the very first and most — I supposed, most vigorous battle. You

know, women like Griselda Pollock, the Guerrilla Girls, all those amazing women in the 1970s and 1980s were fighting that fight. But I’m not sure

that the percentage is that different now. Clearly, it must be more different. Many more women are running museums in charge of —

AMANPOUR: Including this one.

HIMID: Indeed. And being in charge of acquiring work. They listen to us more. We have a bigger say. But I bet the percentage is not 50 percent yet.

Until it’s 50 percent, the battle is not really won.

AMANPOUR: Lubaina Himid, thank you so much, indeed, and congratulations.

HIMID: Thank you very much, indeed, for having me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: Well, that is it for now. If you ever miss our show, you can find the latest episode shortly after it airs on our podcast.

And remember, you can always catch us online on our website and all-over social media. Thank you so much for watching and goodbye from New York.