Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

As Gaza’s death toll continues to climb, will the war expand? I asked Israeli columnist Gideon Levy.

Then, I discussed the threat of a regional conflict with director of the Middle East program at London’s Chatham House Think Tank.

Also, ahead, is Israel actually listening to its strongest allies? Former British cabinet minister turned podcast host Rory Stewart joins me on that

and the U.K.’s changing political landscape.

Plus, “The Upcycled Self,” a new memoir from Grammy-winning artist Tariq Trotter. He speaks to Hari Sreenivasan about music and his childhood grief.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

One in every hundred, that is the staggering number of people killed in Gaza over the past three months, according to Palestinian authorities.

That’s more than 23,000 people, and nearly two-thirds of them are women and children. That human toll is as Western officials visit the region,

expressing increasing concern about the situation.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken today has been meeting top officials in Israel to get them to do more to protect civilians, allow humanitarian

aid in and to try to prevent a wider war that might spread into Lebanon, for instance.

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock has visited the occupied West Bank, where she condemned Israeli settlers’ violence towards Palestinians.

And today, she spoke in Cairo, Egypt. Take a listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANNALENA BAERBOCK, GERMAN FOREIGN MINISTER (through translator): If we are talking about permanent peace, then it must above all be ensured through

security. We always spoke about that in the past. My country knows what that means. Security guarantees, so that violence and terror, and in

Germany fascism, can never again become strong. That requires international responsibility.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

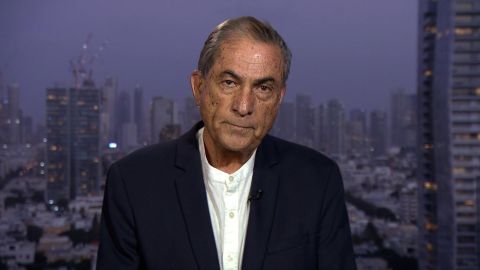

AMANPOUR: But is the Israeli government listening to its strongest allies? And what are the long-term consequences of such destruction? My first guest

says there is no way to “explain Israel’s conduct in Gaza.” He is Gideon Levy. He was an adviser to the late Prime Minister Shimon Peres, then

leader of Israel’s Labour Party, and is now a columnist for Haaretz. And he’s joining us from Tel Aviv.

Gideon Levy, welcome back to our program. Can I just ask you, you know, to explain what you said yourself, there is no answer for this conduct? What

do you exactly mean by that?

GIDEON LEVY, COLUMNIST, HAARETZ NEWSPAPER AND FORMER ADVISER TO SHIMON PERES: Look, by the time we will finish this interview, another baby will

be killed in Gaza. By the time that you will finish your show, there will be another two women killed in Gaza. How long can this last? Israel had the

full right to go for this campaign, for this war, but there must be limits, and we crossed them so long time ago.

But above all, answering your question, where do we aim to? What will it be any better for Israel’s security if another 20,000 Palestinians will be

killed in Gaza? If another half a million people will lose their homes? What does this contribute for the security of Israel? We have to realize

that the goals that Israel had declared are unachievable, or at least partly unachievable. And we should concentrate now about creating a new

reality and not killing and killing for the purpose of killing.

AMANPOUR: Gideon, I want to get into that in a moment, but to answer and to illustrate what you just said about more babies, more women being

killed, there is the latest, and we have to say, graphic video that’s coming in from Gaza today resulting from airstrikes last night.

The hospital at Al-Aqsa there in Gaza says 57 people were killed, nearly 70 injured, at least 10 of those were children, the hospital says. So, the

government keeps saying they’re doing their best to avoid civilian death. The U.S. keeps doing a shuttle diplomacy, which seems principally aimed at

minimizing civilian deaths. Not only that, but also to minimize the chance of an of an expanded war.

But in your mind, having covered so many of these Israel Gaza wars, what is the point? What is the purpose three months in of this, as you put it, very

heavy death toll? What is the strategic point?

LEVY: I doubt very much if there is one. First of all, everyone is paying it’s — his lip service. The Americans, the Israelis, they do their best.

The Americans ask gently Israel to refrain from killing civilians. But the outcome is very clear, it is a bloodbath, and you cannot ignore it.

The only one who ignores it is Israeli media, by the way, if you let me make a remark about them, because the Israelis are the only people in the

world right now who are not exposed at all to what’s going on in Gaza. Nothing.

We were always laughing at the Russian TV covering the war in Ukraine. Ours is much worse because here it is voluntarily, nobody dictates us not to

show the suffer and the punishment of Gaza and Israelis are not exposed to it. But that’s just a, by the way, remark.

There are goals, the prime minister had declared them, namely releasing the hostages and crashing Hamas. After three months I can tell you, we are not

getting closer to both of them. I think about the releasing the hostages, which from my point of view, must be in first priority and they don’t go

together, I think that here we are going far and far. We are much more distanced now than few weeks ago from releasing the hostages, and this

should bother any person who is conscious.

AMANPOUR: Gideon, I want to ask you about that because that is obviously – – we’ve seen the biggest wish and demand from the Israeli people to bring back their loved ones who are still held hostage and under bombardment, by

the way, and under Hamas control inside Gaza.

The Israeli government, when there was the last truce, maintained that only its tough action brought that truce to bear and released more than a

hundred hostages. There are others who say, well, actually, it was negotiations with Hamas through third-parties that did that.

What do you think? What do the Israeli people think is the best way to bring hostages back?

LEVY: It’s even not a question what I think, it’s a question what is the reality. Until now, Israel hardly released one hostage by force. All the

hostages who were released were released throughout negotiation. But Israel always chooses the violent way as the first priority, not only to release

the hostages, by the way, also to solve the problem of Gaza, also to solve the Palestinian issue, it’s always, first of all, let’s try violence. And

then, if it fails, let’s think about something else.

Why wouldn’t we — after this terrible war, why wouldn’t we, once and for all, try another way that we never tried. Why not to start with diplomacy?

Not — why not to start with talking as first priority and shooting as the last priority? But Israel right now is very far off it. Israel is

supporting this war almost wall to wall. Israeli public opinion supports this war and does not want to see ending. And this worries me and makes me

very sad personally as an Israeli.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you about expanding the war? Because that also is a matter of great concern especially to, you know, the surrounding nations

and to the United States and its allies, basically Israel’s strongest allies.

As you very well know, but I’ll just remind everybody what’s been happening, the assassination of the deputy Hamas leader in Beirut this past

week, the killing of a Hezbollah leader in South Lebanon, one of which has been claimed by Israel, that one. Then, you know, there’d been Hezbollah

response in terms of targeting important Israeli targets inside Israel.

And Alon Pinkas, who, as you very well know, a fellow columnist at Haaretz, but also a former Israeli consul general in New York, wrote this. He

basically said, Israel seems resigned to the idea, in other words actually wanting a bigger war, so much so that a “Washington Post” article quoted

U.S. officials expressing alarm and estimating that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is encouraging escalation as a key to his political survival and

further distancing himself from responsibility for the October 7th debacle.

You know, that is an incredibly damning thing for an actual Israeli former government official to say that any country would want an expanded war. Do

you think there’s any truth in that at all?

LEVY: First of all, I can only guess and only hope that there is no truth in it. I think that expanding this war also toward the northern front,

namely against Hezbollah, will be a game changer and will create a reality that Israelis and Israel never met before. We should be aware to it. It’s

very nice to talk here about expanding the war, but what can happen then, I think, is much beyond we ever saw in Israel, in Tel Aviv, in Jerusalem, in

Haifa, and other places.

Listen, I give Netanyahu more credit than most of my colleagues and friends in the way that I don’t think that his personal ambitions are the only

motivation which motivates him. I can’t believe it. I’m sure that his personal motivation is part of his considerations. I’m sure that for him

personally, expanding this war is the only outlet before elections, resignation and inquiry. But to say that he does everything only to

maintain and nothing else interests him, that’s even too much for Netanyahu, I think. I hope I’m not wrong.

AMANPOUR: You have spent a lot of your career, essentially, going against — I’m going to say, going against the tribe, against the herd. You’ve been

in the Occupied West Bank a lot. You speak like this inside Israel and internationally on programs like this one. It must be very difficult for

you, number one. And what is the reaction to the news you bring back from the Occupied West Bank, for instance?

LEVY: It is difficult, but believe me, to be a journalist in Gaza right now is so much more difficult. So, it’s really not for me to complain now

when people are dying in Gaza. I’m really not the issue. It’s not easy. In this war, it became even harder because my best friends, some of my best

friends, and even family members changed their minds on the 7th of October.

It’s unbelievable what happened here. I mean, everything collapsed. All the values that people believed in collapsed only because of this barbaric

attack, which was a barbaric attack, but shouldn’t change any values.

I’m really whistling in the darkness for many years. I’m used to it. I don’t think I have much influence, but I know nothing but to tell what I

think is my truth. And I don’t see any other field that I would like to be active rather than telling the story of the occupation for so many years to

those who don’t want to hear and don’t want to read and don’t want to know.

But by the end of the day, the occupation defines Israel more than any other thing. The apartheid defines the regime of Israel more than any other

thing. And we cannot continue with this blindness. Israelis are living very self-content, happy about their lives, which are usually quite good, not in

times of war, obviously, and they are not even curious to know what is happening half an hour away from our homes.

And half an hour away from our homes, even before this horrible war, there is an inhuman reality which must come to its end one day. And as long as we

continue with this blindness, we will never get to any good place, we Israelis.

AMANPOUR: Gideon Levy, thank you very much. And next, we are going to explore the day after and how this all ends. But thank you so much for

being with us.

And obviously, we want to just remind everybody what Gideon just said, according to press activists and groups like the Committee to Protect

Journalists, some 79 journalists have been killed in Gaza since October 7th. As Gideon pointed out, it is incredibly dangerous for journalists to

be working there.

Now, Hezbollah has carried out its deepest attack into Northern Israel since October 8th. The militant group saying today it targeted an Israeli

military command center in response to the killing, as I mentioned, of a Hamas leader and a Hezbollah commander.

Israel has claimed responsibility for the killing of the Hezbollah commander in Southern Lebanon, but not for the drone strike, which killed a

top Hamas leader last week. Take a listen to what U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has to say.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANTONY BLINKEN, U.S. SECRETARY OF STATE: Well, first in with regard to Lebanon, it’s clearly not in the interest of anyone, Israel, Lebanon,

Hezbollah, for that matter to see this escalate and to see an actual conflict. And the Israelis have been very clear with us that they want to

find a diplomatic way forward, a diplomatic way forward that creates the kind of security that allows Israelis to return home.

Nearly 100,000 Israelis have been forced to leave their homes in Northern Israel because of the threat coming from Hezbollah in Lebanon. But also

allows Lebanese to return to their homes in Southern Lebanon. And we’re working intensely on that effort. And doing so diplomatically.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: A difficult job indeed. Here to discuss is Sanam Vakil. She’s director of the Middle East Programme at London’s Chatham House Think Tank.

Welcome to the program.

So, do you feel, like apparently the secretary of state does, that things are really teetering on the edge right now in terms of the war expanding

from Gaza and across Israel’s northern border into Lebanon?

SANAM VAKIL, DIRECTOR, MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA PROGRAMME AT CHATHAM HOUSE: There is a deep concern, what has become almost normalized

simmering tensions could really boil over. and that’s really where we are. We’ve had attacks coming from the Houthis in Yemen that have attacked

maritime shipping. We have seen back and forth between Hezbollah and Israel at a dangerous level, despite the regular messaging from Hassan Nasrallah

that there is no intention of regionalizing this war. There have been attacks in Syria, attacks in Iraq. And this could very well lead to a

miscalculation.

AMANPOUR: Can I just point out and just emphasize what you just said about Nasrallah. Kim Ghattas, as you know, Beirut-based journalist, has tweeted,

Hezbollah and Iran have signaled clearly, repeatedly, they want to avoid a wider war. Israel keeps testing that position. At some point it will

miscalculate. This was after these assassinations that we’ve just been talking about.

You know, you know the region. Everybody thinks they have — are playing a very clever game, you know, targeted just so, calibrated just so. But is

miscalculation something that could happen? I mean, the Israelis and the Lebanese have already seen what happened across their border in 2006, most

notably.

VAKIL: Yes. I mean, this is the clear risk, and this was part of Anthony Blinken’s primary objective for this trip to message that escalation is not

in anybody’s interest. The problem is that there are two different sort of strategies and timelines underway in the region.

No country, no state or non-state actor in the region is really pushing for escalation, whereas the Israeli government is trying to reset its

deterrence levels since October 7th, and that requires them not only to try and decapitate Hamas leadership, which we know 94 days on from October 7th

they haven’t been able to do, but also to try to push back Hezbollah and make clear that their borders are safe. And that’s what’s ongoing right

now.

Whereas the rest of the region, be it Iran, be it Hezbollah, be it the wider Arab partners of the United States have no interest in seeing this

explode because this could really take things into a new orbit.

AMANPOUR: And just to remind everybody, I mean I covered the 2006 war. It wasn’t a victory by Israel or by Hezbollah. It, at best, was determined to

have been fought to a draw. Then there was a U.N. resolution, I think it’s 1701, that required them to move back from demarcated lands. Apparently,

neither of them kept to that commitment.

So, is there a political solution that actually can reinforce and de- escalate the Lebanon or the Hezbollah Israel tension right now?

VAKIL: Well, Amos Hochstein, another U.S. official, was just in Lebanon, I think, for this very issue, trying to find a face-saving solution to push

Hezbollah back, according to U.N. Resolution 1701, pass the Litani River, and also find a face-saving way for Hezbollah to do that.

There have been suggestions that Hezbollah is pulling back, but at the same time you see the Israelis keep pressing and keep striking at commanders in

Lebanon, and this might be low level escalation, but there will be one day where this goes too far, and this could be a very different war than 2006.

AMANPOUR: I spoke just when all this sort of flared up to the Lebanese foreign minister who is, at the time was in Washington, was about to visit

the White House to talk about these tensions. This is what he said to me, partly.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ABDALLAH BOU HABIB, LEBANESE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND EMIGRANTS: We don’t want any escalation in the war. We don’t want what’s happening in the

south to be spread over Lebanon. We don’t like a regional war because it’s dangerous to everybody. Dangerous to Lebanon, dangerous to Israel, and to

the countries surrounding Israel.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: I mean he’s pretty much laid it out, but it’s very important for the prime minister of that country and ally of the United States to be

saying that. How does Israel — if it does broaden into a big war, how do you separate a war against Hezbollah from a war against Lebanon itself and

the western-backed Lebanese armed forces, which have also been targeted?

VAKIL: I don’t think you can really, and I think this is, again, why —

AMANPOUR: Because the Israelis say we’re not striking, you know, the Lebanese State.

VAKIL: This will be seen as a broader war, and it’s a war that won’t just be about Hezbollah. This will involve the whole system. Hezbollah itself is

embedded into that system, and it is part of the governance system, you know, whether the International Community or the Lebanese like it or not,

and that in itself is the problem.

AMANPOUR: I want to ask you a couple of questions. In “The Times” of London this Sunday, “The Sunday Times,” you might have read it, there was a

front-page article by an Israeli journalist, Anshel Pfeffer, who talked about the stash of papers and documents and maybe hard drives that some of

the Israeli forces had found apparently in Yahya Sinwar’s office.

It talked about there — it was from a couple of years ago, but talked about trying to disrupt any kind of normalization, whether it was at the

time between Turkey and Israel, and it talked about, you know, their sort of strategy in the reason (ph).

Then before there was also — you know, I think Chatham House even put this out, Bronwen Maddox, who used to be a journalist, had interviewed years

ago, Arouri, the Hamas leader who was assassinated. And he had said to her that our aim is to radicalize, in her words, the Palestinian population so

that they do not go towards peace. And Hamas, you know, wants to delegitimize the Palestinian Authority and sort of disable any sentiment

towards peace.

Do you think that’s still what they think? And in which case, how does one get over this? How does one get to a day after?

VAKIL: Well, certainly there are elements of Palestinian leadership, Hamas leadership that have more radical sentiments. I think where we are today is

normalization has slowed, if not stopped completely and will be very far and hard to achieve without a ceasefire and without attending to the

humanitarian issues on the table, as well as without a plan that addresses the issue of Palestinian statehood that has been completely abandoned. So,

that’s, I think, primary task here.

But beyond that what is urgently needed is a pathway that creates a process where Palestinian leaders can work together for reform, accountability,

governance with elections at the end of this process, and an opportunity for Palestinians themselves to elect their future leaders should certainly

be an opportunity given to Palestinians, not one that they’ve had for well over two decades now.

AMANPOUR: Yes, they haven’t gone to elections. Last question. You are an expert and a student of the Iran piece of this whole picture. It also seems

to be trying to staying out of a direct confrontation. How long can that last and what really does Iran want out of all of this?

VAKIL: Well, Iran’s motivations are multiple. Ultimately, the Islamic Republic has always been driven by its own sense of survival above all, and

its security and stability has always been paramount. It has relied on the axis of resistance, this network that it has cultivated and created over a

number of decades as its primary a tool of deterrence against Israel and the United States, two countries that it has defined as its threats in the

region.

And so, it will continue to support the axis of resistance, but at the same time, Iran does see the U.S. as a declining influence in the region, a

destabilizing regional influence above all. And Iran has, over the past few years, restored ties with the Gulf Arab countries, it is looking to forge

stronger economic linkages and be part of an integrated Middle East as well and that, of course, is hard to achieve with its oppositional stance with

the United States, it’s accelerating nuclear program, and of course, this underlying tension with Israel, that is, I think, Tehran is calculating

will increase over this year in particular.

AMANPOUR: And just very briefly before I let you go, do you think there’s a way to pull things back? The Israeli foreign minister told the U.S.

foreign minister today they are looking for some kind of diplomatic solution.

VAKIL: Yes. I think there is, and it begins with a ceasefire. That ceasefire can set the pathway forward to release hostages that have been

completely neglected, as Gideon Levy brought up in your previous interview.

Beyond that, of course, the Arab states, partners of the United States, are going to need to play a really important integral role in guaranteeing

Palestinian security, Israeli security, providing a bridge to Iran, making sure they’re not in a spoiler and what comes next. This is going to be a

long process. Waiting for the day after to begin that process is a bit too late.

AMANPOUR: Sanam Vakil of Chatham House, thank you so much, indeed, for joining us.

Meantime, governments around the world are coming increasingly under scrutiny as they grapple with how to respond three months into a war that

started with their staunch support for Israel’s right to self-defense after the October 7th massacres by Hamas. That has now led to the staggering Gaza

death toll, as we’ve been discussing, in which 1 percent of its 2 million inhabitants have been killed. Here in the U.K., Foreign Minister David

Cameron is now calling for a “sustainable ceasefire.”

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DAVID CAMERON, U.K. FOREIGN MINISTER: The first thing I’m worried about is getting more aid into Gaza. I’m worried about people going hungry in Gaza,

and that leading to potentially starvation. I’m worried about people getting ill in Gaza, and that leading to large scale disease outbreaks. And

we need more trucks with more aid getting into Gaza. And I’ve been talking with the Israeli government and others and visiting Egypt and visiting

Jordan to try and make sure that happens.

Look, of course, Israel has a right to combat Hamas and to stop a 7th of October event happening again. It was an appalling slaughter, an appalling

event. And we support them as they do that. But we must have more aid in Gaza to stop starvation, to stop disease.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: My next guest knows the region very well as the U.K.’s former international development secretary and a former Tory MP, Rory Stewart is

now co-host of the popular podcast, “The Rest is Politics,” which covers issues ranging from this war to climate change and democracy. And Rory is

here with me in London. Welcome back to the program.

RORY STEWART, FORMER BRITISH CONSERVATIVE MP, HOST, “THE REST IS POLITICS” AND ADVISOR, GIVEDIRECTLY: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: You’ve — you know, we’ve had a lot of conversation, you know, and leading up to you now with the different aspects of what might happen

and where we are.

First and foremost, you heard Sanam say that the only way to get out of this is to have a ceasefire and to try to fix this diplomatically. What

does David Cameron and Annalena Baerbock and Keir Starmer, what do they all mean by sustainable ceasefire? And is that a sustainable position?

STEWART: No, it’s not a sustainable position. A sustainable ceasefire isn’t really a ceasefire. It’s a way of saying that they want to signal

that they’d like the fighting to stop, but they don’t want to restrict Israel’s ability to conduct operations.

And a lot of this is to do with Britain Germany’s relationship with Israel. It’s to do with politics inside the United Kingdom. I mean, this is a very

difficult time in the United Kingdom. Jewish community feels under a lot of attack, there’s a rise in antisemitic attacks, horror in relation to the

Hamas attack, and of course the relationship with the United States. But increasingly, of course, this position is untenable.

Quite clearly, what’s happening now in Gaza is not achieving Israel’s objectives. It’s killing, as you said, many thousands of people, including

women and children. Any attempt by Israel to show that it is willing to take revenge and action has been demonstrated weeks ago. And the British

government should, I think, clearly now be coming out for a ceasefire.

AMANPOUR: And then what? Because they all say, I think what they — how they describe sustainable also is, that something that lasts. In other

words, you can’t leave this smoldering fire smoldering and wait for, you know, another massacre and another round of killings of thousands of

Palestinians.

STEWART: Well, the truth is nothing gets fixed overnight. You put in ceasefires in place, ceasefires get broken. They can be temporary. That’s

the business. That’s what happened in Northern Ireland, it’s what happens with conflicts all around the world.

And putting the situation together again is going to be unbelievably difficult. I mean, Israel’s reputation now in the Middle East has been put

back decades. The United States’ reputation in the Middle East has been unbelievably harmed by its support for Israel. It’s very difficult to

imagine countries wanting to be generous and getting involved in reconstructing Gaza that will cost hundreds of billions before you even get

into the points that Sanam was making about the politics, who’s going to lead Gaza, who’s going to be the government.

AMANPOUR: Talking about the U.S. position, what about the British position? The Saudi ambassador to the U.K. was on the BBC today saying,

Israel is a blind spot for the U.K., which makes it a blind spot for peace. And he called on the U.K. to treat Israel like the rest of the world. What

do you think he means?

STEWART: Well, I think he means that with the rest of the world, the U.K. would be calling for a ceasefire. And it’s astonishing that neither Rishi

Sunak nor Keir Starmer is prepared to do that.

I mean, I cannot personally see any justification for these continuing operations. We know from Iraq, we know from Afghanistan that this is not a

way to deal with a terrorist group. Tens of thousands of people were killed in Afghanistan claiming that that was going to somehow eliminate the

Taliban. And of course, now a Taliban government is back in control.

So, the British government is in a completely untenable situation. This word, sustainable ceasefire, is David Cameron, Rishi Sunak, somehow trying

to placate Israel, but they’re not getting any influence on Israel by doing so.

AMANPOUR: And placate their own voters as well.

STEWART: And placate some of their voters as well.

AMANPOUR: But it’s not working.

STEWART: Yes. It’s not even very popular in Britain. I mean, there are many, many people in Britain who are horrified about it.

AMANPOUR: Well, right. Yes, exactly. That’s what I’m saying. It’s not — you know, citizens — I mean, even yesterday, President Biden was

interrupted briefly in a campaign speech in South Carolina at a — you know, a black church where he was trying to appeal to the community there.

And he actually said, I understand your passion and I have been quietly trying to persuade Israel to significantly, you know, disengage from Gaza.

His secretary of state is there right now.

Given all of that, if we just come now to politics, I mean, I don’t expect you to weigh in on how it’s going to affect the U.S. election, but, you

know, there’s going to be an election here too. How do you think this will, or will it affect U.K. politics? And do you think this Tory government is

here for the long-term?

STEWART: I think it’s very likely at the moment that the conservative government will lose and Keir Starmer will come in. But this event, Keir

Starmer’s refusal to call for a ceasefire, is damaging for Keir Starmer and Labour.

There are perhaps 30 Labour seats where Muslim voters are swing voters and they feel very, very angry about this issue. And it’s an issue where Keir

Starmer, who’s looking for ways to differentiate himself, is in danger of being outflanked. If the U.S. changes its position, if Rishi Sunak, the

prime minister, changes his position, Keir Starmer will find himself left behind.

So, there has to be a way to do something that politicians seem to find very difficult, which is to say the Hamas attacks were unbelievably brutal,

horrifying atrocities that killed 1,400 people and Israel had a right to defend itself, and also, enough already, far too many people have been

killed, there is no justification for these ongoing operations.

AMANPOUR: Can I just switch topics about, you know, politics here, which are incredibly, incredibly important, and that is the issue of climate,

something that you’re very, very, you know, involved in.

Right now, former Tory energy minister, Chris Skidmore, has resigned as an MP to protest this government soon acts legislation to issue new oil and

gas licenses. He said, I can no longer stand by the climate crisis that we face is too important to politicize or ignore.

In a word after the COP, you know, in the UAE is this government, do you think, committed to net zero, to the — what it used to be, a really

prominent climate leader?

STEWART: I think the government is trimming. So, I think it’s trying to placate bits on the right-wing of the conservative party that are very

skeptical about issues to address climate change. It’s trying to deal with issues around energy security, trying to deal with economic growth. So,

it’s found itself in opposition.

I think the prime minister believes that climate change is a real problem. He’s trying to do things about it, but he would say that he’s being

pragmatic. And the risk of that is that when you lose the clear policy direction, all the businesses and others who’ve been making investments on

the basis of what governments have said over the last 10 years begin to think, well, maybe the government isn’t that serious anymore. That’s the

real problem here. You — it’s fine to say I’m being pragmatic, but what you’re missing is that the signal that you’re passing undermines an

enormous amount of investment.

AMANPOUR: You were president, if that’s the right word, of GiveDirectly, a charity that believes in giving directly. Now, you’re an adviser, because

your other, you know, work has taken over a little bit. I want to ask you to explain, I think, a partnership you’ve gone into with the Scottish

government to help distribute funds designed, you know, by COP to mitigate the effects of climate change, and that’s in Africa. Tell me about that.

SNOW: Yes, so, one of the great insights is that with climate change, the most important thing is to get support to people before the climate

disaster happens.

If you can get support to people before the flood occurs, then they can move livestock, they can move their houses. If the flood hits them, and

then you provide support afterwards, their lives have been completely devastated. It costs you 10 times more, and of course communities are

destroyed.

We are now in a world where, with A.I., with computer technology, we can predict more accurately we could in the past. It’s still not easy, but more

accurately where floods are going.

So, one of the things we’re doing with the Scottish government and others is looking at anticipatory action, and in particular what GiveDirectly does

is to understand that the most easy thing you can do, the most effective thing you can do, is to give unconditional cash. Because every house is

different.

You know, you may want to fix your roof, or you may want to set up a small business, I may want to get my kids back into school, or I may want to buy

food. Cash is what allows you to make the choice. It’s radically humble respectful way of providing assistance.

AMANPOUR: And very quickly, we’ve got 15 seconds. Universal basic income is a bigger version of GiveDirectly. Some people say, oh, no, it makes

people lazy, it doesn’t let them work, et cetera.

STEWART: So, the evidence is incredibly strong. It’s a revolution in international development that unconditional cash is now outperforming in

almost every study, almost every conventional development intervention. It’s transforming nutrition, education, health, shelter. Cash is the way

forward.

AMANPOUR: And on that note, Rory Stewart, thank you so much indeed.

STEWART: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Co-host of “The Rest is Politics.”

And next, we revisit a recent conversation with Grammy Award-winning artist Tariq Trotter, better known as Black Thought, from the hip hop group The

Roots.

Trotter turned to music after a series of traumatic experiences growing up, including the murder of his own mother when he was 16. He details these

tragedies in his new memoir, “The Upcycled Self,” and he speaks to Hari Sreenivasan now about how his childhood impacted his career.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARI SREENIVASAN, INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: Christiane, thanks. Tariq Trotter, also known as Black Thought to most of us who have listened

to him for so many years as part of The Roots, thanks so much for joining us.

First of all, congratulations on this book. I am not surprised that you’re venturing out into this sort of written word expression. What does “The

Upcycled Self” mean?

TARIQ “BLACK THOUGHT” TROTTER, CO-FOUNDER, THE ROOTS AND AUTHOR, “THE UPCYCLED SELF”: I’m from Philadelphia from a specific place and time

there, where, you know, you had to sort of move through life with a layer of scar to — of callus, right? Of scar tissue, almost as a protective sort

of thing, you know, and it serves a purpose at — you know, one time in your life, or at least it may.

And then, as we evolve, as we, you know, mature, as we move on in life, you know, these things no longer service in the same way. So, the upcycle self,

it speaks to, you know, the wisdom it takes to recognize when to, you know, leave a thing in the past, to adapt a way or, you know, to move forward in

a different way.

SREENIVASAN: You start out this book with something I suspect anybody would want to leave in the past and it’s a horrendous story of you setting

your house on fire as a little kid playing with toys, you know, being a curious kid and starting a fire with your TV. What were some of the

repercussions of that event?

TROTTER: Yes. You know, the book actually begins with the fire. It took place when I was six years old. I burned my — you know, my family home

down. And, yes, I think, you know, the story to follow puts you in into the mind of — you know, the story is told in the spirit of the phoenix.

So, I’m — you know, I think I very much emerged, you know, from the flame. So, it begins with the fire, even though that wasn’t my first traumatic

experience, even at that young age, it was — you know, it was a watershed moment in that way. And it was a moment — it was my earliest memory of a

time after which, you know, things would never be the same, you know.

But, you know, talk about just curiosity, right, of a child and the tremendous amount of grace and wisdom that it took my mother, you know, for

her to extend and not come home, you know, after having lost everything and sort of, you know, (INAUDIBLE) her main concern was that no one had been

hurt.

And, you know, I wasn’t mad that I wasn’t punished in the way that I’d expected to be. And I think, there’s beauty and there was a — there was

great value in that. And my mother sort of recognizing that it was my curiosity and it was my, you know, imagination that led to — you know, to

the event.

So, she was able to help me — you know, to encourage me to lean into that curiosity and into that imagination by getting into the arts.

SREENIVASAN: So, what did that do to your mom, do you think? I mean, because she had worked so hard to — you know, your father had been

murdered earlier, and she was raising you two, and she’s built all these things. She saved up. She’s kind of built something normal for the two of

you as normal as can be, and then to literally see it go up in smoke, what does that do to her psyche? What did you find out over time?

TROTTER: It really — I mean, over time, I came to realize just the tremendous amount of strength and, you know, resilience that she had.

Because you think back, you know, when she lost my father, my father was very young. He was, you know, maybe 26. My mother was still very young.

When you — at the time, there’s no way that she could have fully recovered because I think maybe — you know, maybe four years or so had passed if

that.

So, yes, she was — the whole family was still very much in the grieving process. You know, so this was sort of, you know, back-to-back loss in that

way that, yes, I mean, you know, we should have been and could have, you know, been devastating, but, it wasn’t in many ways.

SREENIVASAN: So, who were the men that you looked at as role models or father figures during this impressionable time?

TROTTER: My earliest examples of manhood, you know, aside from, you know, what I saw in my grandparents, like in my — you know, my father’s father,

who I saw, you know, rarely and in my mother’s stepfather who I referred to as my grandfather, they were sort of the examples.

But then there were — you know, the gentlemen that were in my mother’s life. So, the people that my mother would date, my mother’s male friends, a

colorful cast of characters, you know, set many examples. Some were good examples, some were bad, you know. But yes, that was sort of what I had.

And I had, again, my older brother, who, for all intents and purposes, was away from the family because he spent — you know, he essentially came to

adulthood in juvenile — in the juvenile justice system and then, you know, you graduated.

SREENIVASAN: Your mom figured out somehow that your curiosity also translated into the ability for you to express yourself artistically, and

she pushed you into that. How did she do that?

TROTTER: I think the earliest indication of, you know, her sort of understanding that thing, that dynamic was, you know, just in her

encouraging me to take art classes I think in the summer.

Well, you know, even before I took visual art classes, my mother, she signed me up for choir and, you know, she’d always encouraged me to sort of

lean into music. But when she found out visual art was sort of my thing, then she was really, really just super supportive of that.

And, yes, she — you know, at every turn she would, register me for a thing. Anything that was free, I was definitely going to do, but you know,

the — all the other things that we — anything we could afford or save up for she also would encourage.

SREENIVASAN: You also are very vulnerable in this book and you write about some very painful moments. In terms of your mom, you basically have kind of

a scene that you play out, and it’s to try to essentially rescue her from what would be a crack house. What was that like?

TROTTER: I mean, you know, it was — that may have been — I mean, I think about low points of my life, you know, dark moments. You know, I don’t know

that I’ve ever been as resigned as, you know, just sad and down, you know, bad as I was in that moment. I mean, it’s something that I think I’ve

grappled with, over the years when you’re in that moment.

You know, I went to go — you know, I was — we’ve been looking for my mom for a period of days, you know, a couple of days have gone by and I tracked

her down and she was in a drug house. And, yes, you know, I thought I was, you know, showing up like the calvary. I was there to — you know, to save

my mom, you know, take her out of this place. And, no, it was the heart — I had to accept the harsh reality of just, you know, the matter of fact

that she, in that moment, preferred to remain, right? She didn’t want to leave.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TROTTER: So, I couldn’t convince her to leave. And it was — yes, that was — it was just a super gut-wrenching moment for me as a young person, you

know, because I was — I mean, you know, as I recall, I may have been — I was 14 — you know, 13 or 14 years old.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. Later in the book, you were — you’re not living with your mom. You’re someplace else. How did you find out that your mother was

dead?

TROTTER: Yes. My mother was murdered when I was — I think I just turned 16 — or somewhere between 15 and 16 my mother was murdered. I moved out of

the City of Philadelphia to Michigan, to Southfield, Michigan, right outside Detroit, to stay with an uncle, with my — one of my father’s

brothers who I never met, you know, just because, the streets had gotten so crazy. My neighborhood was crazy. Lots of my friends were, you know, being

murdered or, you know, sent to prison. And it was — you know, it was the middle of, you know, 1980s drug crack epidemic and everything that sort of

came along with it.

So, my family has sent me to Michigan for a while and, you know, it didn’t work out in Michigan, but when I came back to Philly, it was — we were —

we had agreed that I wouldn’t return to my old neighborhood. So, no, I wasn’t living with my mother. I was staying in an apartment that my

grandparents own. She was sort of living her life and I was living mine. I had school. I had work.

And, you know, days, sometimes weeks will go by without us, you know, seeing one another, but we would speak on the phone. And I just remember,

there was a period, during which a few days had gone by when no one in the family had heard from or seen my mother, which also, again, wasn’t, you

know, out of, out of the norm, right?

And over, you know, a period of days through that process of elimination, my mother was identified as a Jane Doe who had, you know, turned up in the

morgue.

So, yes. And, you know, the way I found out, I mean, it was — I don’t know, I think my whole family, you know, even by that point, had become to

just experiences that would otherwise be, you know, life shattering, traumatic experience for other people. We were just so used to loss and

grief that, yes, I don’t know that they pulled any punches. I don’t know that — I think, you know, they — my aunt, as I recall, my aunt and my

grandmother, so, you know, two — my grandmother and her sister just confirmed with me that the body, the Jane Doe that had been, you know,

found that we suspected was my mother. Yes, that was that — it was Cassie.

You know — and, you know, we just started to move, move forward with the arrangements. You know, it was — it’s wild. I didn’t even — I don’t

remember having shed a tear during my mother’s death until I saw her body being, you know, lowered into the ground.

SREENIVASAN: At that time, you’re also at a creative arts high school, the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts, CAPA, right? And

we know who they are now, but who was in that high school at the time that was, I guess, your competition, your classmates, your peers that were also

performers that went on to be more successful?

TROTTER: I went to that school, which was sort of Philadelphia’s version of LaGuardia in New York City, or, you know, like “Fame.” It was like

“Fame,” the TV series and the film. And, yes, I was a visual arts major, but there were just very many singers and instrumentalists there who were

already, you know, forces to be reckoned with in their own right.

So, Questlove who, you know, he and I met there and started The Roots, but there was also Boys II Men, who before they even came together as Boys II

Men were parts of, you know, other male ensembles who, you know, just beautiful, you know, harmonies. And, you know, so it was — walking through

the halls of that school made me feel the way it must have felt to, you know, like in the days of Corner Boy do up (ph), you know what I’m saying?

They would be — yes, at any given moment, someone will break out into song, you’ll turn a corner and there’d be one yay and nay, you know,

working on a harmony. So, it was that. And it was a huge confidence builder for me. You know, and I mean, to see kids that I knew, you know, doing —

like going on, you know, to onboard a network.

SREENIVASAN: So how did you and Ahmir Questlove find each other?

TROTTER: Questlove and I found each other in the principal’s office, where we were — yes, it probably wasn’t the first time we — you know, we’re in

the space together, but we were like two ships of, you know, passing each other at sea in the night. usually, and it was — in this instance, I think

I was going — I was on my way out on a suspension, which, you know, I got suspended sometimes.

So, I was there. I’d done something and I was being suspended from school. So, I was in the office and, Quest walked in. I think he was bringing like

flowers and apples to the faculty. And he had on a jacket, a hand painted denim jacket, which was one of my side hustles at the time was I would do

hand painted denim, like, you know, jeans and jackets and I would sell them, you know, really out of my locker.

So, the jacket that he wore that day and I think maybe his necklace too that he had on was a sort of the gateway to a dynamic that will grow where,

you know, I was able to put him on to parts of the elements of the culture and, you know, hip hop music that he had been exposed to yet and vice

versa. And, you know, we became an odd couple and we remain as such.

I think, you know, maybe both of us, you know, just had a desire to — you know, for brotherhood, to experience that brother, because even though I

had a brother, I still hadn’t really experienced that dynamic in the way that, you know, other siblings had. So, it was great, yes, to have a

brother at that time.

And then, our relationship evolved into something else when it became a business relationship and it evolved into, now, what is a marriage. Yes,

yes.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TROTTER: We went from brotherhood to marriage.

SREENIVASAN: So, I wonder, you formed this group, at the time it wasn’t called The Roots, right? What was it called?

TROTTER: Before we were called The Roots, we were called Square Roots.

SREENIVASAN: Square. That’s right. So, Square Roots. And I wonder, the Square Roots, in the type of influences that you were mixing to make the

type of music that you wanted to make and put that in the context of what was happening at the time, because what we see of The Roots now, which is a

mix of so many different influences, is not what was kind of playing on the streets and the car stereos as you were growing up and this group was

starting.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

TROTTER: Yes. I think, you know, it was a huge challenge, because not only did we not, you know — like, we didn’t look. We didn’t have the same, you

know, aesthetic as our contemporaries at the time, nor did we sound or feel — nor did, like, our music sound or feel like theirs.

So, you know, in a mixtape, mixed radio show era, The Roots music sort of stood out like a sore thumb. And it’s wild that, you know, it stood out in

its musicality, you know?

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TROTTER: Because we it was live instrumentation, and it just didn’t feel like — you know, the standard at that time, because it just felt more

electronic, and, you know, we had to fight to represent those influences, right, in order to — you know, to expand sort of the palette of the

culture, you know? And, it’s something that — you know, I mean, it’s taken some time, but I think over time, we — The Roots has, you know, been

hugely responsible for reestablishing that standard.

And, you know, now you see, you know, folks who go out to tour, to do gigs, studio sessions, you rarely see — I mean, even within the realm of hip

hop, people who don’t use live instrumentation.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: Is there — you have been in so many different formats. You write about the fact that you were a graffiti artist, at the time, that

could be considered vandalism, depending on who saw your work, right? You’ve done visual arts. You’ve been rhyming for decades. Here you are

writing a book. I mean, what is it about self-expression that keeps you wanting to try it in another format?

TROTTER: It’s the challenge of taking on a new sort of format, working in a new medium of allowing, you know, one discipline to inform another, it

keeps me engaged. And, you know, I always meet, you know, folks, sometimes it’s one person, sometimes it’s 10, sometimes it’s more, but, you know, if

there’s one person that, you know, my work, my story has resonated with in a way that, you know, has, you know, given them any deeper insight into

themselves or into their story, then it’s worth it. You what I mean?

And that is — you know, it’s a two-sided therapy, right? Like, this is my — like, this is — it’s — the work, the process is cathartic for me in

that way. So, yes, I just keep, you know, accepting new challenges because there’s nothing that — you know, I mean, there’s so many people that I’ve

seen come from Philadelphia and try a thing and win. And those who have won, all those many people who I’m able to list who have won, they have won

because they didn’t give up. You know what I mean?

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TROTTER: So, you know, I feel like if anything, any challenge that that I take on, as long as I stick to it, I’m going to be able to see it through

to fruition.

SREENIVASAN: The book is called “The Upcycled Self: A Memoir on the Art of Becoming Who We Are.” Author Tariq Trotter, also known as Black Thought

from the Roots, thank you so much for your time.

TROTTER: Thank you. This has been awesome. Thank you so much.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And finally, tonight, Rue David Bowie. That’s my French. The David Bowie Street. Paris has named a street after the late rock icon on

what would have been his 77th birthday.

The celebration was attended by friends and fans, which include the mayor of the 13th arrondissement of Paris, or district, who came up with the

idea. Jerome Coumet remembered Bowie’s pioneering genius, saying that he allowed people “to be freer and to feel like they could grow wings by

listening to his music.”

The City of Lights was where the British Trailblazer first performed outside the U.K. back in 1965 and where he recorded two of his albums and

fans can look forward to a new vinyl LP that’s set to be released on April 20th. And there’s more amazing news, “Waiting in the Sky” includes four new

songs that were recorded during the Ziggy Stardust era.

So, let’s leave you now with some of Ziggy. Thank you for watching and goodbye from London.