Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Now, immigration is, of course, a top issue in the 2024 presidential election. As Biden and Trump head to the Mexico border today. Our next guest moved to the United States from Peru at the age of nine and is part of the diverse Latino community, who number now 64 million people across the nation. In her new book, “LatinoLand,” author Marie Arana sheds light on the lesser-known history of Hispanic America. And she’s joining Michel Martin to discuss the impact of this vote in the upcoming election.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Thanks, Christiane. Marie Arana, thank you so much for speaking with us.

MARIE ARANA, AUTHOR “LATINOLAND”: Oh, it’s such a pleasure, Michel. Thank you.

MARTIN: So, the title of your latest book is “LatinoLand.” You emphasize in your book throughout that Latinos are not recent additions to this country. I just wanted to ask if you would just read a little bit from the author’s note at the beginning of the book.

ARANA: OK, absolutely. This is from the preface, really, to the book, my author’s note in the very beginning. And it reads, we were Americans long before the founders dreamed of a United States of America. Our ancestors have lived here for more than a half millennium, longer than any immigrant to this hemisphere, and still we come. Indeed, although we arrived long before the pilgrims, and although we account for more than half of the U.S. population growth over the last decade, and are projected to lead population growth for the next 35 years, it seems as if the rest of the country is perpetually in the act of discovering us.

MARTIN: What do you mean by that, it seems as if the rest of the country is perpetually in the act of discovering us? Tell us what you mean by that.

ARANA: We are virtually marginal, virtually invisible. We’re not in the history books. Nobody teaches the fact that we have fought in every war since the establishment of this country. We fought in the Revolutionary War. We fought in the Civil War all the way up to Iraq. That is invisible. It’s invisible to people that we represent. The 26 percent of the U.S. Marine Corps is Hispanic, is Latino. We have fought for this country a long time. And of course, if you are Mexican-American, you are part, certainly, indigenous, which is to say that you have inhabited this territory for millennia. In pre-Columbian times. So, what I mean is, perpetually in the act of discovering us, I think the image of the person jumping over a fence, is, to many people, what a Latino represents. And, in fact, we represent so much more, so much more history. People don’t realize, for instance, Michel, that the first navy admiral of this country, David Farragut, His name was actually Ferragut, and he was Hispanic. His bust is, you know, about three blocks from the U.S. White House.

MARTIN: In Farragut Square or Farragut Square. OK.

ARANA: Farragut Square, yes. Nobody goes by and says, hey, great Latino sitting there on the park. But — so, that’s what —

MARTIN: And why do you think that is? Why do you think that is?

ARANA: Because we are the ethnicity that most intermarries in this country. We intermarry across races and ethnicities all the time. In fact — and I think history tells us that the first time that there was race mixing and in as massive a quantity in the world, on this planet, was among the Latinos of this hemisphere, once the Spanish came and intermarriage began. And we have continued to intermarry here in the United States. So, there is that sense that we lose our identity. My grandchildren, for instance, are a small percentage of Latino, because the marriages have been with other with other races, other ethnicities. And yet, there is a very strong, very strong cultural bond between Latinos, even though, we may be from different parts. Maybe we are Cubans and don’t identify with Mexicans. Maybe we are Dominicans and don’t identify with Peruvians much, but we are still unified in the sense that when we come to this country, the label itself unifies us. And we learn that there are many, many, connections between us.

MARTIN: Of people who identify or would be identified as Latino, you’d say Mexicans would probably be the largest group, right?

ARANA: Mexicans are very definitely the largest group. There are 37 million. So, more than half are Mexicans.

MARTIN: More than half. So, this is a group of people who you say — people have often said, hey, we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us. So, are there aspects of that story that you think are particularly important for people to know?

ARANA: Well, history has moved populations, certainly Latino populations in this country. You know, when I came in — it was 1960 when I came, there were countable 2 million Latinos in this country. Now, there are 64 million. So, what happened? Let’s start with the fact the Spanish colonial territory of Mexico went all the way from California the way to Kansas, and it went all the way from the Rio Grande to Colorado. So, this was a huge, massive space that basically the American administration, the U.S. administration in the Westward Ho movement, the Manifest Destiny movement said, go, take your family. Put us to — carry a stick, put the stick down. It’ll be your land. Without any consideration of the fact that they were poaching, that they were invading. This was an invasion and incursion of sorts. And, you know, families went happily off and created farms and ranches and whatnot, and pushing the Mexican population off of their land. After that, we had — of course, the Puerto Ricans, because America took over Puerto Rico, it — in the Mexican War, in the Cuban War, also with Cuba, the island of Puerto Rico became an American territory. So, Puerto Ricans came streaming into the United States. So, the second largest group here. Of course, the Cubans came after the Castro revolution got rid of the very corrupt system that the United States was supporting in Cuba under the Batista regime. And so, the Cubans came in in 1960s and became a large group. So, all of this so-called blowback of American policy in the United States has created these groups, has created these immigrant groups in the United States. And that is history that’s worth studying.

MARTIN: You — I want to go back to the — I want to talk about the nomenclature, because that’s something that you talk — you spend some time on in the book. Is it Latino? Is it Hispanic? Is it Latinx? You say that, labels we never chose for ourselves, Hispanic, Latino, Latinx, Latine, have been adopted and rejected and adopted again, willy-nilly, one after the next, causing grave doubts about their validity and reflecting the extent of our identity crisis. All of this, mind you, in an effort to portray us as a strong and unified whole. So, just say a little bit more about that. Like how do you think about that and what do you think about that?

ARANA: Yes, the nomenclature is really important and interesting. The — you know, we are Peruvians, we are Ecuadorians, we are Argentines, we are Mexicans, but when we come to this country, as I say, we become — we start to be called these names. The first person to say that we were Latinos or Latin, as he would have said it, was Napoleon. I mean, he had designs on conquest in the hemisphere. When Napoleon invaded Spain, suddenly, Napoleon’s heart jumped because, you know, Spain had this considerable colonial power in Latin America with all kinds of extractions to enjoy. And so, Napoleon as said, OK, you all are Latins. You’re Latins like us, like the French, like all the places that I’m trying to conquer, you know, are going to be Latin. So, we became Latin America. We became Latin Americans. We became Latinos to a certain extent And then, comes the 1970s with Nixon. And Nixon tries to — Nixon has a very strong feeling about Latinos or Hispanics, whatever you want to call them, because he grew up in California. His father was a grocer. He worked with people in the agricultural fields that he was selling their goods, and they were all — all the agricultural workers, of course, were Mexicans or Central Americans. So, he wanted to make that sort of a strong electorate and to be part of his support population. And so, he gave them a name. And we became Hispanics at that point. So, the name stuck to a certain degree. But then came the academics, the intelligentsia, which said, OK, we have to be more inclusive, more gender inclusive. And so, we’re going to be Latinx. Well, that was trying to change the language because, the calling yourself Latinos is a grammatical point. It’s not a point about gender. And so, that only stuck to the extent that 2 percent of the population of Latinos, only 2 percent use it. And a lot of people reject it. So, where are we with that? The point is, most people call themselves Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, Dominican Americans. So, the aggregate term isn’t necessarily the one that we use you in a unified sense.

MARTIN: This is an election year in the United States. And so, there’s always this question of what’s the Latino vote going to do, right?

ARANA: Right, right.

MARTIN: Whose interest is it going to serve? You have a lot to say about that. That’s one of those misconceptions, right, that you that you are pointing up in your book and in your other writings, which is that the idea that there’s the singular or Latino bloc is just false.

ARANA: Absolutely.

MARTIN: Would you say a little bit more about that?

ARANA: We come from very different backgrounds. Those who come from countries that have been really racked by communism tend to be more conservative politically. Naturally, the Cubans are very much that way. The countries where there has been, let’s say, dictatorships that worked and that actually did something and achieve something, they tend to be also conservative. So, when you try to actually define where we are politically, it’s an impossibility. Because in truth, the — we don’t tend to think in the binary. I, like many Latinos, will switch sides and have switched sides many times depending on who is running. We tend to be independents more than anything else. But because there are so many of us who haven’t stepped up to vote because there is such a large percentage of Latinos who stay home and don’t go to the polls, there is an opportunity to recruit. And Republicans have been very successful in recent years in recruiting that lot of people, particularly because more and more Latinos, especially from Central America, from Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, are becoming evangelical. And of course, as we know, the evangelical churches encourage you to be political. Then they encourage you to go to polls and express your political stripe. So, that is — it’s a very fluid, very changing population, and it could go any way in any election.

MARTIN: One of the things that has been really striking is that despite the former presidents, I think it’s fair to say really outrageous and demeaning remarks about Mexican immigrants at the launch of his 2016 campaign, accusing them of saying, you know, they’re not sending their best, they’re sending criminals, drug dealers, rapists. You know, we are — I think we all remember. And despite his efforts, you know, at various times to shut down the border, despite these draconian policies, separating children from their parents at the border when they crossed without prior authorization, he got almost 30 percent of the Latino vote in 2016. And he actually did better in 2020.

ARANA: Right.

MARTIN: And I just think a lot of people find that really intriguing.

ARANA: Absolutely. And there are very good reasons for that. They’re very good reasons for that. The Koch brothers, David Koch and his brother, have actually created a group called Libre. And Libre goes around the country, and recruiting the massively people to the Republican Party. And why is that? Well, let me give you a couple of reasons why. First of all, we are largely a people of faith. OK. You can say, OK, Catholic faith, evangelical faith, evangelicals are growing more and more by the minute in the Latino community, as I’ve just said. But — so, we are a people of faith. And any group that we’re going to vote for is going to be very upfront with that. We are largely very devoted to family life, anything that appeals to family when Libre does, Libre understands that. The — of course, the other thing and the hidden thing that people don’t realize is that many Latinos, the majority of Latinos are really worried about the immigration situation. They really want that flow to stop. 80 percent — more than 80 percent of Latinos in this country are U.S. born. We are not foreign born. We are mostly U.S. born. We all speak more than 80 percent — 90 percent speak English. We are afraid, as much as anybody in this country, about those waves of immigration that are coming across the border. Many of the strongest people, anti-immigration people, are people who came as children.

MARTIN: I think that sort of the perception is that there would be some sort of affinity or sympathy for people who are coming across, some sense that, well, you know, they must have a good reason. So, why is it that you said that people are worried about it? I mean, that because they feel, what, that they’re going to compromise their own economic standing or because they feel, what, that just the sense of I waited my tur, why don’t they wait their turn? I mean, tell — just say more about why that is.

ARANA: Well, if you’re going to talk about immigration and feelings about immigration, you have to talk about the undocumented. OK. The undocumented here are an extraordinary group of people. People — I think people assume that the undocumented are a burden on society. And in fact, I think it was the Carnegie Institution that did a survey and established that the undocumented population of Hispanics have zero-net effect on government budget. So, there are — the — zero-net effect on a drain on budget on the government budget. So, let’s start with that. One out of three —

MARTIN: I’m just — this is where I have to jump in. Maybe in the long- term, but certainly that can’t be true in the short-term, certainly in the situation that we’re seeing now, and you just can’t have 300,000 people cross the border in a month and then not have it have some impact on local budget. So, I take your point that in the long-term, that’s certainly true.

ARANA: In the long-term.

MARTIN: But in the long term —

ARANA: Yes.

MARTIN: — it cannot be true.

ARANA: In the long-term, it is very definitely true. And I think a Pew Research survey that happened just a — not very long ago, it must have been in — within the last three years, established that one out of three undocumented Hispanics owns their home. Think about that. Now, we can talk about, OK, this last group of the 2023, 2024 may be different, but we have to believe the surveys to some extent. And the —

MARTIN: Let’s go back to your original point. When you say that people are worried about it, what are they worried about? Are they worried that this group of new migrants will reflect poorly on the community as a whole or do they —

ARANA: That’s part of it.

MARTIN: — worry that their own economic foothold is not strong enough and firm enough to tolerate what seems like a shock? What is it that they’re worried about? Or how are people sort of seeing — thinking about this?

ARANA: I think that’s very much related to the image of the Hispanic. I mean, none of us wants us to be — I mean, people cringe when something like this happens, right? That we are seen to be a burden when we are not, and we know we are not. The population, when I go back to the beginning of what I said, being marginalized and invisible, because you don’t see the great contributions of the population. You only see the headlines where you see people jumping the fence or coming — you know, streaming into the farmlands in Texas or swimming across the river, and you’re made to feel that this is a stain on the rest of us. That’s the problem.

MARTIN: Marie Arana, thank you so much for speaking with us.

ARANA: Thank you so much for having me, Michel. Pleasure.

About This Episode EXPAND

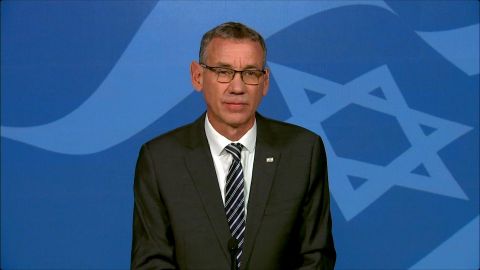

More than one hundred people have been killed whilst gathered around food aid trucks in Gaza city. Mark Regev joins the show. Tech journalist Kara Swisher is chronicling her career in a new memoir, “Burn Book.” “LatinoLand” author Marie Arana on the impact of the Latino vote in the upcoming election. Josh Paul resigned from the State Department soon after Oct. 7th in protest. He joins the show.

LEARN MORE