Read Transcript EXPAND

On the face of it, Casey Gerald is a quintessential American, rising from a troubled childhood in Texas to the heights of academia and business.

But over the course of what looked like a blessed life, Gerald says he realized that in reality, success in America is fraught with false promises.

His new memoir is 'There Will Be No Miracles Here' and you told our Hari Sreenivasan why, despite defying all the odds, he refuses to be a poster child for the American dream.

Casey Gerald, the book's called 'There Will Be No Miracles Here.' What are some of those themes that you touch on and how does your personal life almost end up mirroring some of the deeper conversations that the country needs to be happening, having right now?

Yeah, in a lot of ways, you know, I tell people sometimes I lift myself into a dead end and rope my way out.

I think the country is in a very similar spot.

This book is not just a memoir; my agent gave it to a friend of hers who is an old Royal Victorian Shakespeare actor and he said you know when I was reading your book I didn't feel that I was reading a memoir, I felt I was reading a history of America.

Now, I've seen America from the very bottom to the very top.

I obviously grew up this little poor, black, queer, damn near orphan in Oak Cliff Texas, but I went on to Yale and Harvard and I was at Lehman Brothers in the summer of 2008, I was in Washington the first years of the Obama administration, I was at C-PAC in the early months of the Tea Party, I was at George Bush's dinner table.

I mean, I'm almost like Forrest Gump, you know, I just happened to be a lot of places and this was my report back and what I saw was that I could not only tell you about a life, but the beauty of memoirs that you can write through the 'i' and get to the 'we' and when I did that I think I was able to show folks how the country actually does and does not work and how we got to this horrific place we find ourselves and how we might get away from it.

Tell me about growing up in South Oak Cliff.

What where your parents like?

What was life like?

My mother, I tell folks, is kind of like a mix of Blanche Dubois from a Streetcar Named Desire and a 1980s Whitney Houston, you know, she was just this magical, fragile, beautiful creature.

She suffered from mental illness and from bipolar and she disappeared when I was 13 and it wasn't until I wrote this book that I realized I completely misremembered the event.

I'd always thought she left when I was 12 but then I started writing the book and I found this sort of homework from when I was 13 and her signature was on it and initially I thought, 'Wow, I got to give this book money back because yeah I don't know the plot to my own life, man.' It was really alarming.

But then I realize that it's possible that this absence of memory will be a far more interesting thing to bring language to.

I was struck watching Dr. Ford's testimony a few weeks ago by how absurd of a standard they were trying to hold her to as it pertained to her memory because what I learned through this book is that often the absence of memory is the clearest sign that some really bad stuff happened.

There's a passage that you have after she returns, once, that you write, 'After the hug I looked at her and felt a tingling desire to slap, no, to disfigure her and after I disfigured her I wanted her to grovel, to walk back from the airport, not ride in the car, to go without sleep and food and sit on a mat outside the house and chant 'I'm sorry' from sunup to sundown, to let her throat parch with thirst and sorrow, to forget how to laugh and instead to cry and cry until crying lost all meaning and the tears dried up and her eyes were filled only with the images of all the wrong she'd done.' That's your mother.

Yeah.

Things improved.

I think that is a sign of things improving, actually.

Kids are cut to pieces all the time and expected to be quiet about it.

If I wanted to have some healing in my relationship with my mother, I had to have some space for honest anger and been a peaceful liar is not progress to me.

You also have passages where you're talking about during your first relationships, you finish up a phone call with the young man and you flip on televangelists that are railing against what would be your actions as sins, your feelings as sins.

How do you reconcile what you're feeling?

It's this sort of cognitive dissonance of the world's reality that you're watching through the TV and how you're feeling and being.

Well it's two things there.

First off is what I really wanted to do with this book is to bring worthy language to the Beauty and Challenge of loving another boy, in my case, a challenge in part because, as you just lay, out we live in a society that hates gay people and teaches us to hate ourselves whether it's the God we're given or the path to success we're offered, but it's more complicated than that.

I didn't want to write a dissertation about that.

I wanted to climb into my intimate human experience and so I find these moments where I am very honestly trying to figure out how to love this boy and how to love God simultaneously and what happened, in my case, I had to let go of the God I was given to find the God that I needed and in doing that, being gay was a great gift actually, because there was no reconciling it at all.

The more I travel the country with this book, the more I see that just because people have left the church does not mean they have forfeited their spiritual lives and that was very much the case for me.

One of the reasons that Yale got a look at you in the first place is because of football and you have a really interesting kind of relationship with it.

Your dad was a standout player in the state.

He, in a way you describe him sacrificing for Ohio State things that he maybe didn't sacrifice for his own family.

My dad was, is still considered by a lot of people to be the greatest high school football players in the history of the state of Texas.

He goes on, he was the second black quarterback at Ohio State under the legendary Woody Hayes and when he was a sophomore, he broke his back in a game against Purdue and a few games later, five or six games later, Ohio State makes the Orange Bowl and Woody wants them to play and this is his identity, he wants to play, so he decides to suit up.

Before the game a man comes and offers him an envelope with cocaine in it and he takes it, never taken it before.

He went on the game of his life.

He was Orange Bowl MVP and he never took, never played another game without using and things spiraled from there.

Now when I was born, I walk into my sixth grade classroom and all I get as it pertains to a story is South Oak Cliff star threw away life for drugs and a big picture of my dad on the Dallas Morning News behind bars.

That's the only story I get and it wasn't until I wrote this book that I saw that my dad would not have been that addict that I came to know if it wasn't for this moment of glory, you see what I'm saying?

So the football material, and in some ways this is a sports book, in part is trying to use this sport, this game as almost like a test tube for the ways in which our structures and systems lead people to certain decisions.

You write that Yale was the loneliest place of all for you and, yet, you know, throughout the book you're talking about being on the football team, having a sense of camaraderie with these gentlemen, helping lead young black men on their time on campus, being part of different student groups.

What was what was that loneliness stemming from?

I arrived at Yale and I write in the book that I felt that it was like when the when a coolie meets a Brahmin, yeah, and I felt very clear sense that from black people on campus even hey we're black and you're a nigger, yeah.

I went back a few years later and a senior administrator was talking to 50 18 year old black boys you know black men and he was a very respected person on the faculty and administration.

His message to them was, you can be a token, but if you're going to be a token just be the best token you can be and that broke my heart man because it spoke to what I'm trying to work against in this book.

So often we are told as kids, we'll give you the keys to the kingdom, we'll give you the degree and the job and the invites to the parties, invites to this great show, in return, we're going to ask you to leave pieces of yourself outside and what I'm trying to say because I've lived it is that that burden, that bargain is not worth it.

Did you see that tour success or your ability to punch through was almost like a salve for this machine.

Oh, well the Casey Gerald's exist, he made it out.

I don't necessarily have to tinker with the infrastructure problem, the systemic problems because hey, here's this guy, he's out.

Absolutely.

It's that great line in Bonfire Of The Vanities.

Wolfe writes 'Something's got to keep the steam down.' When I first went to Yale there were posters that were put up in every school in Dallas that said look who's going to Yale.

He did it, you can too and at that time I felt real proud of myself.

I said Oh boy yeah I'm a big star and then I saw more and I learned more and I lived more and felt real sad and I should have wept because when we send that message we tell kids who don't make it quote unquote that it's their fault and we tell the rest of us that well there's nothing else that we have to do so I write in the book about meeting George Bush and we were in a buffet line at his presidential library.

It was a very random meeting and a few months later he was out in Beverly Hills at an event and he was telling folks my story as sort of this you know look at what America can do and I felt increasingly complicit.

So you disbanded the nonprofit that you had created, which went out and tried to inspire MBAs in small communities all over the country.

In some ways this is supposed to be the path of success, that you'd gone to a fantastic Ivy League undergraduate school, the best business school in the country, you've now found these other people that can start this company.

You know the goal the current system has is to scale this solution up big and here you are, I'm out.

Why?

What I'm saying with this book is that we find ourselves in a situation as a society, perhaps as individuals, that doesn't work.

Maybe it works for those Harvard Business School alumni, but it doesn't work for the vast majority of us.

There must be a better way than one savior, one organization, one centralized figure solving the problem that ought to be on the backs of every person in this society.

I'm not trying to get people to give up on this notion of the American dream.

What I'm actually trying to do more so is ask you to hold on to something else, which is the notion of the American machine, how the country actually works, right, this conveyor belt that leads most young people, especially from neighborhoods like mine, or like Appalachia, or rural Montana where I've don work, from nothing to nowhere while picking off the chosen few, like me, and the reason you can't say well Casey Gerald's the miracle let's celebrate him is because you have to also look at the fact that kids in my neighborhood are expected to earn twenty one thousand dollars a year less than our parents were expected to earn, you have to look at the fact that 13 million children go to sleep hungry in this country, you have to look at the fact that one in 30 children don't have a place to go to sleep at all that's stable.

One Casey Gerald does not justify the suffering of so many children in America and their suffering is enabled by choices that we have made and not made as it pertains to the kind of country we want to live in, the kind of support we want to give to people and the kind of outcomes that we will accept if not endorse and I think if this book does anything it hopefully can help us see that this machine isn't working but that's not a cause for despair, it's a cause for action and I think that that that action gives me a lot of hope.

Casey Gerald, thanks for stopping by.

Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

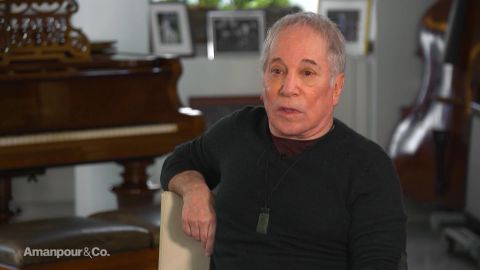

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Alexis Bloom & Alisyn Camerota about Roger Ailes and interviews legendary musician Paul Simon about his career. Hari Sreenivasan speaks with author Casey Gerald about his new memoir “There Will Be No Miracles Here.”

LEARN MORE