Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to ‘Amanpour and Company.’

Here’s what’s coming up.

> This is America.

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: He reshaped the American media and politics.

Fox news founder Roger Ailes.

I’ll speak with the director of a new documentary and an anchor that worked closely with him.

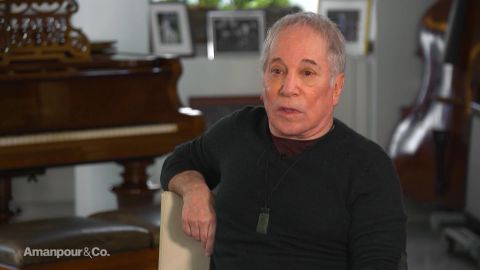

Plus the poet for a generation, a musical shape shifter.

Up close and personal with Paul Simon.

I had to let go of the god I was given to find the god that I needed.

Kneeling at the altar of the American dream only to see that the gods were dead.

He spoke about his amazing life story.

♪♪♪

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone.

Now you have no doubt heard of Fox news and its politics.

There are hundreds of those migrant caravan folks that have made it up to the border.

But do you know the real story?

The one behind the headlines?

The founding principle was to give conservatives a voice on television, but it ended up as the voice of right wing politics in Washington and around the country with an outside influence and Roger Ailes, the chairman of fox, backed by Rupert Murdoch was one of the most powerful men in media before his long history of he was fired in 2016 and died within a year.

Was he a monster?

A genius?

Or both.

A new documentary, divide and conquer, shows the vast influence he had over the country. It all started when he a young aid to President Richard Nixon.

The liberal elite has a choke hold on the national news networks but local television stations in Wisconsin and in Utah had their own news programs and they’re hungry for footage.

So it was a proposal that the Nixon white house with taxpayer dollars fund an operation that would interview republican members of congress in Washington and fly the footage to the local stations so they could get a message out to their constituents without having to rely on the institutional press.

And Roger Ailes is all over it saying, I can do this.

Now it never happened, but the idea goes straight into what fox news is all about.

So Alexis bloom is the director of that new film and she joins me from New York alongside Alisyn who is now anchor of CNN’s new day but she began her career as a reporter and anchor at Fox news.

Ladies, welcome to the program.

Thank you.

Alexis, let me start with you and ask you to react to what he has often said.

He basically said he had a vision for the average American.

He wanted to provide, you know, somewhere for the average American to be able to get their news.

What did he mean?

What was his vision?

What was the average American to him?

The think the average American was an underserved audience. Always called it the underserved audience which was in between New York and l.A.

He defined it as antithetical to the coastal elites.

He always defined it as the people he knew when he was growing up.

He grew up in Warren, Ohio, and he was like those are my people, simple, hardworking, blue collar Americans, and I don’t know whether that’s really the case.

It sounded so great and so wholesome, but he had a much more kind of ambitious and mercantile perspective.

He wanted to capture the conservative base and keep them glued.

When he did.

I turned to Alisyn, I built Fox understanding the pressures, worries, and aspirations of average Americans.

I love these people.

How did that translate in marching orders to you, the workers?

The worker bees, if you like, at Fox?

Well, it’s interesting.

What he told me, and this is almost verbatim.

What he told me was that he figured out that 48% of the cable viewing audience was conservative and that 20% was liberal and 20% he said were swing voters, meaning independents. He said that he figured the business model that if he could capture this 48% that previously hadn’t heard their own voice reflected back at them, then he would really have something.

And, in fact, he did that.

So the way it translated in terms of programming was that he would often call me into his office if he thought that I hadn’t been conservative enough.

And I said I was not supposed to be conservative or liberal.

I was supposed to be a journalist and fair to both sides.

And he would tell me things like unless you get these conservative talking points down, you will lose the audience, he would say.

And I would try to tell him that I thought he was underestimating the audience.

I thought the audience could hear both sides, and he would bang his fist on the armchair and say don’t tell him how to program television.

And I basically lost every fight.

Well, yes.

And he was a larger than life character backed by an even larger than life character, Rupert Murdoch that had incredible influence on leaders of governments from Australia to Britain to America and points in between.

So given this idea of shaping the network toward one political point of view, I want to play this bit from an interview you did from the documentary and that was the associate producer at Fox.

This is what he tells you about the working atmosphere inside.

I was told my first place on the job, Roger has this place bugged.

He’s got the newsroom bugged.

He’s got the elevators bugged, all the talent offices bugged.

Don’t talk [ bleep ] about Roger.

Don’t talk about how much you love Hillary Clinton because he’ll fire you if they hear you talking like that.

How many people confirmed that point of view?

The political marching orders and the talking points that one shouldn’t stray from?

Well, they’re the talking points, you know, don’t say you love Hillary Clinton but I think more part of that is having the whole place bugged and if you went off topic, you know, either on camera or in private, it would be heard about, you know, if you weren’t loyal and obedient to the message, the man, and the corporation.

And, you know, he says, you know there’s surveillance and if you express an alternate point of view it will be noted.

Many people said that.

Glenn Beck said that.

Ask Alisyn.

She had personal experiences with that too.

I’ll get to that in a moment, but it is really remarkable.

And you bring that up quite effectively.

The fear that Libyans and al Qaeda types were out to get him.

But you also actually layout where these grievances, the politics of personal victimhood and the politics of grievance were born.

He was a hemophiliac and that comes from his mother.

Tell us how that plays into his world view.

I don’t know exactly.

But he had a very intimate relationship with fear.

He was a hemophiliac and growing up in the 1950s in Ohio there was little to no treatment.

Apparently they used to hang him upside down sometimes so that the blood didn’t pool.

He thought he was going to die.

So he was incredibly fearful and you know, I think that informed him all throughout his life.

You spoke about the paranoia.

There’s two ways to go.

You either become very cautious or kind of the stereotypical thing is you become very reckless.

You live each day like it was your last and you have incredible appetite for things and he was certainly the latter.

He had this boundless ambition but at the base of it was a very profound fear and this kind of growing paranoia.

I’m going to play you this bound bite again from the documentary.

You document this anecdote about his childhood.

This was the legend that went around.

Just listen.

Roger was on the top bunk, and his dad walked in and opened up his arms and said jump Roger, jump.

And Roger jumped and his father stepped away and Roger fell on the ground.

And his father looked down on him and said don’t trust anybody.

It sounds so dramatic and Alisyn I wonder whether that legend went around Fox as sort of this is who Roger Ailes is?

Well, it’s interesting, he told me a different legend about his childhood.

He told me that he was in a hospital bed and that he overheard doctors telling his parents that he might not survive.

And he told me very tearfully, I mean, in a heartfelt moment — Roger could get quite emotional — that no kid should ever have to hear that.

And he told me that he decided there and then that if he did live, and if he did survive, he would fight every single day.

And that’s what taught him to fight.

But what is important to say is Alexis figured out in making this movie was that that tale that he told about the jumping off the bed is one of these tales of the mythologizing that he started to do about his own childhood and about himself.

And after that I didn’t know if it was true or not.

He liked being the underdog.

He liked being seen as the fighter that was never going to leave his battle station.

So I don’t know any more what part of his childhood was real.

And then, to Alexis, as you’re making this film, you’re going before fox news and before Alisyn’s experience with Roger Ailes and talking to these other people that worked with him and in particular, Kelly that was a marketing consultant and had a run in with him in the late 1980s.

Fast forward from this victim to practically an aggressor if you listen to these stories.

Listen to this.

I mentioned to Roger that I was going to sign a contract with one of the big national this was a career making contract. You hit that level, yu made it.

But once we got into his car, we barely pulled away from union station and he leaned over and he said I can really help you, but if you want to play with the big boys, you have to lay with the big boys.

It just came out of nowhere.

And it was very transactional.

So I just said I’ll think about it and get back to you.

He said if you don’t agree now, there’s a good chance you won’t later on.

I said, well, we’re just going to have to take that risk.

I wasn’t getting my calls returned to the national committee and after a couple of weeks I thought, there’s something wrong here.

So I asked a friend to ask around.

And he called me back very quickly afterwards and said, you’re on the no hire list.

The no hire list?

And then all of a sudden it all fit into place.

That’s what Roger had done.

That was the end of my career.

So listening to that now in the year after me too where we have heard so many similar stories, it’s remarkable that this was apparently going on so long before he was caught up for it.

Alisyn, you experienced a certain amount of harassment and in the end, it was those allegations that toppled him from fox and from his very mighty perch.

Yeah.

I think that Roger played loose with the rules a lot, and I guess he didn’t think they applied to him.

He was so powerful at fox that there was no court of higher authority that you could ever go to.

So when he set up quid pro quos or when he said things that were grossly inappropriate, there was no one to ever turn to.

It was quite unpleasant having I didn’t find the sexual harassment that I experienced to be career ruining as that woman did, but I certainly hit a dead end at fox, and I think it’s because I wouldn’t spout the conservative talking points he wanted me to spout.

It was quite clear.

He told me that you have to do this in order to get ahead, and I wasn’t willing to do that.

So it was always Roger’s way or the highway.

Let’s talk about the political impact.

It’s not just a media company.

It’s one that is campaigned for, lobbied for, directed, and as he himself boasted, has got several republicans elected president, and he felt he still had work to do, Alexis, to elect more like-minded presidents.

So we know about Nixon.

We know about the first George W. Bush.

All of those things, but fast forward a little bit now to President Trump.

What did you learn in the documentation about his active health and fox’s active help in the trump campaign?

He was very active.

I don’t think Donald Trump was necessarily Roger Ailes first choice but he had given him an ample opportunity to prove himself and way before the election he put him on the show every Monday and then given him interviews on all the major shows in Fox.

Not talking specifically about political strategy, about the economy, about immigration, you know, giving him kind of political legitimacy.

Nobody else did that.

Donald trump might have been famous for the apprentice, but there’s a pivot from fame into kind of political sphere and Roger certainly gave him that.

That’s what happened.

I watched it happen.

That’s when he would talk about national and international issues.

That’s when he became a pundant.

He suddenly started being seen as somebody that had a voice in the political arena.

I watched the creation of the Donald Trump presidency and I think he can thank Roger Ailes for that.

It’s really a remarkable story.

Divide and conquer.

Thank you both very, very much indeed.

Alexis Bloom and Alisyn.

Thank you so much.

So if Roger Ailes set the political chew for contemporary America as so many believe then Paul Simon remains champion of the counter culture in music.

Bridge over troubled water.

‘Mr. Robinson,’ ‘Graceland,’ you’d be hard pressed to find a music fan of any age that doesn’t know one of his songs.

His career spans decades from the most famous musical duo of all time.

They began as Tom and Jerry in the 1950s to a blockbuster solo career.

Now Paul Simon is out with a new album in the blue light and on the heels of the global fair well tour.

We got off to an inpromptu start.

I want to ask you what that is.

Is it a throwback?

I guess you could say a throwback.

I first used this on the boxer in Nashville.

You performed it at a rather iconic moment several weeks after 9/11.

They had the policemen and the firemen and then the camera pans to you.

New Yorkers are unified.

We will not yield to terrorism.

We will not let our decisions be made out of fear.

We choose to live our lives in freedom.

[ applause ] ♪♪ ♪ I’m just a poor boy, I squandered my resistance for a pocket full of mumbles ♪ ♪ all lies and jests, still a man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest ♪ ♪

Take me back to that moment, if you can.

What I remember most about that moment is coming from the dressing room to the studio where my mind is focused on what I’m about to do but I passed by these lines of firemen and policemen and the reality of the situation I was performing in, the context that I was performing in was very powerful.

Very powerful.

It was very emotional and it’s seldom that I feel my heart pounding.

These songs are legendary and they have been going for more than 50 years.

‘The Boxer,’ ‘Sound of Silence,’ ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water.’

All of those classics.

They still mean so much to so many people.

Are you surprised by that?

Absolutely.

I was 22 years old when I wrote ‘The Sound of Silence,’ I think.

Because when I did the last performance on this final tour, the last song that I sang was ‘The Sound of Silence’ and I thought how at 22 did this even happen?

I didn’t know.

Same with ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water.’

I wrote the song and when it was finished I said, that’s better than I usually do.

But what I come to realize overtime because there’s a few other songs in this category, ‘Graceland’ would be in this where you feel as though you’re a conduit and the song is coming through you.

You’re shaping it, but you’re absolutely surprised at what’s happening and you don’t know why and you don’t know where it comes from but I recognize that that happens sometimes and it’s lead me to be a more spiritual person because of the mystery of it.

So you mention the central park concert of course sounds of silence was among the many that you sang there and we’re just overlooking Central Park.

I want to play a little bit of that concert.

♪♪ ♪ people without speaking ♪ people hearing without ♪ people writing songs that voices never share ♪ ♪ no one did, the sound of silence ♪♪

You sing 10,000 people maybe more.

There’s probably hundreds of thousands.

Tons and tons and there’s a huge wave and applause.

Do you remember to this day that moment??

Yes, I remember.

I remember playing that.

The two concerts that I did in Central Park.

That concert I did with Graceland people. I wanted to talk about that, but let’s talk about Graceland because that was one of your solo triumphs.

That was yet another departure for you and another breakout and the music was spectacular and your singers and musicians were amazing, but there was a political controversy, wasn’t there?

There were angry and you shouldn’t have broken the boycott on South Africa and why were you going there?

What do you think about that all of these years later?

I think they were completely disingenuous about it.

First of all, we didn’t break any boycott.

There was no rule about recording with black South African musicians.

First of all, the musicians voted whether they wanted many he to come.

I didn’t know that.

But I found out later on that they voted.

What they wanted to know was how much are we going to be paid and will we get credit?

And so that was easy, you know?

Of course they were going to get credit and royalties and I paid them at that time what was triple scale.

So everybody was perfectly happy.

Nobody thought that we were going to have a hit.

And my experience with traveling around the world is that artists or particularly musicians are perhaps the most insightful in describing what a culture and a country is like.

They talk to everybody and other musicians from other countries and like, on the Graceland tour, he was my great teacher about South African politics.

When you came back to the United States, you were at Howard University.

Yes.

You remember that, and this guy at Howard University, again, to your credit, you were taking them on and engaging them in this criticism they had and they thought that you didn’t have any right to take the music, the musicians that you didn’t give them enough credit.

Anyway, this is what he said.

How can you justify going there and taking all of this music from this country — it’s nothing but stealing.

It ain’t nothing but stealing.

How can you just go and tell me —

It’s a collaboration.

You don’t believe that it’s possible to have a do you believe that collaboration is possible between musicians?

Between you and them, no.

Why?

You don’t understand.

Why, because I’m white and they’re South African?

You don’t understand at all.

Well, you are saying something that they, these musicians, in fact, disagree with.

I was completely unprepared for that attack.

But again, as it turns out, they were members of a political party on the far left of the constellation of many political parties in South Africa.

They were the most violent.

I only learned about this because she became beloved all over the world and still perform to this day.

And of course joseph, that was the leader, he said that it was the first time he ever hugged a white man and he was really taken by it.

That he always remembered that.

Joseph was — he was almost angelic.

He’s a very spiritual man and was very aware of what could be accomplished with the music from Graceland and what could be accomplished in the context of helping black South Africans.

It’s very hard to get the truth but musicians will often bring it on a level that goes right to the heart.

It’s really true that music is the universal language.

How do you feel after all of these years of telling that truth of retiring?

You just gave your last concert in corona.

Correct?

Not far from where were you raised and where you grew up.

What was it like?

What was it like singing and performing but knowing this was the last time that you were going to deliver that truth?

Well, first of all, I don’t intend for it to be my last performance. Intend for it to be last time that I go on tour.

I anticipate that I will perform again after taking a break.

But I’d like to do it for specific causes, and I’d like to do it for my own pleasure in concert halls that have pristine sound and with perhaps different musicians that I admire.

I’m ready to say I examined this music as much as I can.

I think it would be good for me to stop and think for a while.

Listen to music again, read, travel, stop.

And then see what happens.

You know, a thought comes in — a musical thought comes into my head through all of these years and I say oh, how does that become a song.

Now I say, no, don’t solve it that way.

Just leave it along.

Let’s just see what happens.

I already have — not that I actually believe in this.

I don’t believe in legacy — well, I mean, I don’t believe that there’s any importance to it.

Put it that way.

Of course people have legacies.

But I have already left a great deal of my thinking.

I just turned 77.

So I have already left my thinking through these songs.

Some of which are very well-known good to stop and what else will I think of or maybe I won’t.

Maybe I’ll just take a rest.

Are you tired?

Yeah.

I’m tired.

I’m not physically tired.

I’m mentally tired in a way that I don’t know how to explain exactly.

It’s not like I couldn’t do another album now at the same qualitative level as I have done the last two or three albums, which I think are as good as I can do, as I have ever been.

I think I could do that.

But I’m not sure that that’s the most interesting choice for me.

I think that there might be something that could be more interesting, but I don’t know what it is.

Let me ask you about in the blue light then because that’s the latest album.

Where does that fit into this evolution that you’re talking because it’s older songs that you’re repurposing, correct?

That’s right.

These are songs that I thought were well written good songs that were overlooked or — people didn’t notice them when I put them out because they were on an album where other songs were hits or they were on an album that wasn’t a hit.

Whatever, they were odd.

So I took these songs that I really liked and I rerecorded them, changing the lyrics on oh, maybe half of them here and there.

Changing the harmonies.

And again, the context and the musical setting gives the songs a fuller meaning and also it’s mellow and fits the lyrics in a way that’s important this time around.

Can I ask you what is your favorite song?

Do you have a favorite song?

Of all time?

Of all time?

No, I don’t.

No, I don’t.

But I do enjoy singing some of the ones that are — I really do enjoy singing the boxer.

I really do enjoy singing sound of silence.

On this last tour I finally found a way of singing bridge over troubled water that was neither like the Simon and Garfunkel recording that was like that vocal.

I wrote that song.

That’s bridge over troubled water and I wrote it.

I think you said about bridge over troubled water that when you were writing it, you realized that it was exceptional.

Yeah.

I thought it was better.

It was better than I usually did and it came — it flowed the way I described earlier as if it came through me.

Obviously it’s part of the Simon and Garfunkel legacy.

Will you ever make peace with each other?

Oh, I think we can — yes.

I don’t know how to you know even approach that.

There’s too much damage that was done, you know?

But, you know, it’s like somebody that I have known since I was 11.

So I understand.

I think I understand why it happened.

But I think it’s best to stay away.

And so I do.

We tried.

We came and did several reunion tours.

Especially the one where the Everly Brothers joined us.

They were a pleasure.

But it just doesn’t work.

What can I say?

It doesn’t work.

It’s really not unusual in duos or groups if they do stay together these kind of groups, they’re just there for the money, you know?

That’s not about — it’s not because there’s a musical reason to stay together.

The Beatles broke up because they were — I think they were finished as a musical entity.

And finally, you know, you talk about taking a rest and doing other things, but you’re very, very involved, for instance, in the environment, and that’s one of your big missions, right?

I really think that the number one priority for all of us should be the environment.

I think we have damaged the environment to a degree that’s so dangerous that we might be talking about an extinction of life on the planet.

And all of these other concerns that we have, human rights, human rights, racism, sexism, gender equality, what — all problems that humans have, they’re all human problems, but if we don’t ensure that the planet continues to nourish us in a way that it has for hundreds of thousands of years, all of those problems will be moot because there won’t be any life and I feel just really guilty about the fact that I’m leaving this to my children and their children.

The tour before last I gave all of the money to the half earth on the last tour that I did, every city that I played, I would leave a small amount, $25,000 as a thank you to say thank you, first of all, thank you.

That’s what I was doing.

Trying to leave it like a trail of bread crumbs through the forest so people if they were following it would enjoy it.

That’s what I think is the most important thing to do and when I do begin to perform again, that’s where I’ll give all of my money — all of the proceeds from whatever.

That’s a great legacy and a great promise and a great mission. Thank you very much.

Thank you.

It was lovely to talk to you.

Nice to meet you too.

Thank you.

Paul Simon, what an incredible career and still going strong.

He’s 77 years old and he still packs those massive, massive stadiums.

On the face of it, Casey Gerald is a quintessential American, rising from a troubled childhood in Texas to the heights of academia and business.

But over the course of what looked like a blessed life, Gerald says he realized that in reality, success in America is fraught with false promises.

His new memoir is ‘There Will Be No Miracles Here’ and you told our Hari Sreenivasan why, despite defying all the odds, he refuses to be a poster child for the American dream.

Casey Gerald, the book’s called ‘There Will Be No Miracles Here.’ What are some of those themes that you touch on and how does your personal life almost end up mirroring some of the deeper conversations that the country needs to be happening, having right now?

Yeah, in a lot of ways, you know, I tell people sometimes I lift myself into a dead end and rope my way out.

I think the country is in a very similar spot.

This book is not just a memoir; my agent gave it to a friend of hers who is an old Royal Victorian Shakespeare actor and he said you know when I was reading your book I didn’t feel that I was reading a memoir, I felt I was reading a history of America.

Now, I’ve seen America from the very bottom to the very top.

I obviously grew up this little poor, black, queer, damn near orphan in Oak Cliff Texas, but I went on to Yale and Harvard and I was at Lehman Brothers in the summer of 2008, I was in Washington the first years of the Obama administration, I was at C-PAC in the early months of the Tea Party, I was at George Bush’s dinner table.

I mean, I’m almost like Forrest Gump, you know, I just happened to be a lot of places and this was my report back and what I saw was that I could not only tell you about a life, but the beauty of memoirs that you can write through the ‘i’ and get to the ‘we’ and when I did that I think I was able to show folks how the country actually does and does not work and how we got to this horrific place we find ourselves and how we might get away from it.

Tell me about growing up in South Oak Cliff.

What where your parents like?

What was life like?

My mother, I tell folks, is kind of like a mix of Blanche Dubois from a Streetcar Named Desire and a 1980s Whitney Houston, you know, she was just this magical, fragile, beautiful creature.

She suffered from mental illness and from bipolar and she disappeared when I was 13 and it wasn’t until I wrote this book that I realized I completely misremembered the event.

I’d always thought she left when I was 12 but then I started writing the book and I found this sort of homework from when I was 13 and her signature was on it and initially I thought, ‘Wow, I got to give this book money back because yeah I don’t know the plot to my own life, man.’ It was really alarming.

But then I realize that it’s possible that this absence of memory will be a far more interesting thing to bring language to.

I was struck watching Dr. Ford’s testimony a few weeks ago by how absurd of a standard they were trying to hold her to as it pertained to her memory because what I learned through this book is that often the absence of memory is the clearest sign that some really bad stuff happened.

There’s a passage that you have after she returns, once, that you write, ‘After the hug I looked at her and felt a tingling desire to slap, no, to disfigure her and after I disfigured her I wanted her to grovel, to walk back from the airport, not ride in the car, to go without sleep and food and sit on a mat outside the house and chant ‘I’m sorry’ from sunup to sundown, to let her throat parch with thirst and sorrow, to forget how to laugh and instead to cry and cry until crying lost all meaning and the tears dried up and her eyes were filled only with the images of all the wrong she’d done.’ That’s your mother.

Yeah.

Things improved.

I think that is a sign of things improving, actually.

Kids are cut to pieces all the time and expected to be quiet about it.

If I wanted to have some healing in my relationship with my mother, I had to have some space for honest anger and been a peaceful liar is not progress to me.

You also have passages where you’re talking about during your first relationships, you finish up a phone call with the young man and you flip on televangelists that are railing against what would be your actions as sins, your feelings as sins.

How do you reconcile what you’re feeling?

It’s this sort of cognitive dissonance of the world’s reality that you’re watching through the TV and how you’re feeling and being.

Well it’s two things there.

First off is what I really wanted to do with this book is to bring worthy language to the Beauty and Challenge of loving another boy, in my case, a challenge in part because, as you just lay, out we live in a society that hates gay people and teaches us to hate ourselves whether it’s the God we’re given or the path to success we’re offered, but it’s more complicated than that.

I didn’t want to write a dissertation about that.

I wanted to climb into my intimate human experience and so I find these moments where I am very honestly trying to figure out how to love this boy and how to love God simultaneously and what happened, in my case, I had to let go of the God I was given to find the God that I needed and in doing that, being gay was a great gift actually, because there was no reconciling it at all.

The more I travel the country with this book, the more I see that just because people have left the church does not mean they have forfeited their spiritual lives and that was very much the case for me.

One of the reasons that Yale got a look at you in the first place is because of football and you have a really interesting kind of relationship with it.

Your dad was a standout player in the state.

He, in a way you describe him sacrificing for Ohio State things that he maybe didn’t sacrifice for his own family.

My dad was, is still considered by a lot of people to be the greatest high school football players in the history of the state of Texas.

He goes on, he was the second black quarterback at Ohio State under the legendary Woody Hayes and when he was a sophomore, he broke his back in a game against Purdue and a few games later, five or six games later, Ohio State makes the Orange Bowl and Woody wants them to play and this is his identity, he wants to play, so he decides to suit up.

Before the game a man comes and offers him an envelope with cocaine in it and he takes it, never taken it before.

He went on the game of his life.

He was Orange Bowl MVP and he never took, never played another game without using and things spiraled from there.

Now when I was born, I walk into my sixth grade classroom and all I get as it pertains to a story is South Oak Cliff star threw away life for drugs and a big picture of my dad on the Dallas Morning News behind bars.

That’s the only story I get and it wasn’t until I wrote this book that I saw that my dad would not have been that addict that I came to know if it wasn’t for this moment of glory, you see what I’m saying?

So the football material, and in some ways this is a sports book, in part is trying to use this sport, this game as almost like a test tube for the ways in which our structures and systems lead people to certain decisions.

You write that Yale was the loneliest place of all for you and, yet, you know, throughout the book you’re talking about being on the football team, having a sense of camaraderie with these gentlemen, helping lead young black men on their time on campus, being part of different student groups.

What was what was that loneliness stemming from?

I arrived at Yale and I write in the book that I felt that it was like when the when a coolie meets a Brahmin, yeah, and I felt very clear sense that from black people on campus even hey we’re black and you’re a nigger, yeah.

I went back a few years later and a senior administrator was talking to 50 18 year old black boys you know black men and he was a very respected person on the faculty and administration.

His message to them was, you can be a token, but if you’re going to be a token just be the best token you can be and that broke my heart man because it spoke to what I’m trying to work against in this book.

So often we are told as kids, we’ll give you the keys to the kingdom, we’ll give you the degree and the job and the invites to the parties, invites to this great show, in return, we’re going to ask you to leave pieces of yourself outside and what I’m trying to say because I’ve lived it is that that burden, that bargain is not worth it.

Did you see that tour success or your ability to punch through was almost like a salve for this machine.

Oh, well the Casey Gerald’s exist, he made it out.

I don’t necessarily have to tinker with the infrastructure problem, the systemic problems because hey, here’s this guy, he’s out.

Absolutely.

It’s that great line in Bonfire Of The Vanities.

Wolfe writes ‘Something’s got to keep the steam down.’ When I first went to Yale there were posters that were put up in every school in Dallas that said look who’s going to Yale.

He did it, you can too and at that time I felt real proud of myself.

I said Oh boy yeah I’m a big star and then I saw more and I learned more and I lived more and felt real sad and I should have wept because when we send that message we tell kids who don’t make it quote unquote that it’s their fault and we tell the rest of us that well there’s nothing else that we have to do so I write in the book about meeting George Bush and we were in a buffet line at his presidential library.

It was a very random meeting and a few months later he was out in Beverly Hills at an event and he was telling folks my story as sort of this you know look at what America can do and I felt increasingly complicit.

So you disbanded the nonprofit that you had created, which went out and tried to inspire MBAs in small communities all over the country.

In some ways this is supposed to be the path of success, that you’d gone to a fantastic Ivy League undergraduate school, the best business school in the country, you’ve now found these other people that can start this company.

You know the goal the current system has is to scale this solution up big and here you are, I’m out.

Why?

What I’m saying with this book is that we find ourselves in a situation as a society, perhaps as individuals, that doesn’t work.

Maybe it works for those Harvard Business School alumni, but it doesn’t work for the vast majority of us.

There must be a better way than one savior, one organization, one centralized figure solving the problem that ought to be on the backs of every person in this society.

I’m not trying to get people to give up on this notion of the American dream.

What I’m actually trying to do more so is ask you to hold on to something else, which is the notion of the American machine, how the country actually works, right, this conveyor belt that leads most young people, especially from neighborhoods like mine, or like Appalachia, or rural Montana where I’ve done work, from nothing to nowhere while picking off the chosen few, like me, and the reason you can’t say well Casey Gerald’s the miracle let’s celebrate him is because you have to also look at the fact that kids in my neighborhood are expected to earn twenty one thousand dollars a year less than our parents were expected to earn, you have to look at the fact that 13 million children go to sleep hungry in this country, you have to look at the fact that one in 30 children don’t have a place to go to sleep at all that’s stable.

One Casey Gerald does not justify the suffering of so many children in America and their suffering is enabled by choices that we have made and not made as it pertains to the kind of country we want to live in, the kind of support we want to give to people and the kind of outcomes that we will accept if not endorse and I think if this book does anything it hopefully can help us see that this machine isn’t working but that’s not a cause for despair, it’s a cause for action and I think that that that action gives me a lot of hope.

Casey Gerald, thanks for stopping by.

Thank you.

A course for hope in difficult times.

That’s it for our program tonight. Thank you for watching and join us again tomorrow night.