Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

The White House faces a congressional grilling over its support for Saudi Arabia. What does that mean for the devastating war in Yemen? I’ll ask a

top official from the anti-Saudi coalition.

Plus, behind every hateful view expressed online, there is a person. Meet the podcaster who’s trying to empathize one comment at a time.

And, his story is almost as famous as his art, Vincent van Gogh. My conversation with the actor Willem Dafoe who’s playing him on the silver

screen.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

The U.S. Defense Secretary, James Mattis, and the Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, face a grilling on Capitol Hill today when they went up to brief

senators on Saudi Arabia. A bipartisan caucus denounced what they deemed the administration’s feeble response to the murder and dismemberment of the

Saudi journalist, Jamal Khashoggi. They want the U.S. to stop supporting the devastating Saudi-led war in Yemen.

Pompeo said that the suffering there “grieves him” but that it would “be a hell of a lot worse if the U.S. weren’t involved.” Republican Senator, Bob

Corker, said that he was skeptical of forcing the administration’s hand but is nonetheless dissatisfied by its actions.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BOB CORKER; U.S. SENATE REPUBLICAN: I think 80 percent of the people left the hearing this morning, not feeling like an appropriate response has been

forthcoming.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Yemen was already the poorest country in the Middle East when Shiite Houthi forces supported by Iran took advantage of the difficult

transition of power to launch a coup against the Saudi-backed government in 2015.

The Saudis and its Sunni partners backed by the United States responded with devastating force, viewing the conflict as a proxy war with Iran.

Tens of thousands of Yemenis have been killed since the war erupted three years ago and millions of them, half the population are on the verge of

famine according to the United Nations.

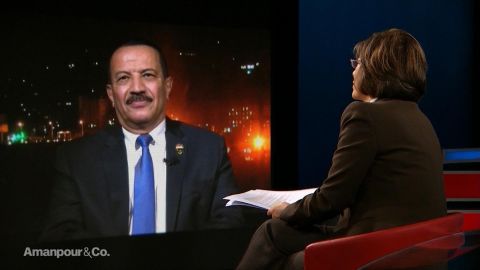

Now, the U.N. is mediating the first phase of negotiations to end the war, due to start next month in Sweden. Will all know or any of the side seize

the opportunity? I asked the man who represents Yemen’s Houthi coalition, the foreign minister, Hisham Sharaf Abdullah, who joins me from the Capital

Sana’a.

Minister Abdullah, welcome to the program.

HISHAM SHARAF ABDULLAH, HOUTHI-BACKED FOREIGN MINISTER, YEMEN: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So, there you are sitting in in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, and your country is literally being torn apart as we speak. We understand

that there are going to be peace talks starting in December. Can you confirm that that is going to happen, that the Houthis back that and that

you will somehow be represented?

ABDULLAH: Yes. We have already expressed our willingness and readiness to attend those peace consultations. They are no talks or negotiations yet.

They are out of consultations to build the trust measures between the parties.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, let’s take first steps first. But can I ask you, is everything on the table or are there areas that the Houthi say, “No, we’re

not going to discuss that”? Do you have red lines ahead of this first step?

ABDULLAH: Really, everything will be on the table for the trust building measures to prepare for these negotiations. We have to understand this,

first consultations, build the trust between the warring parties and then, we will go to the negotiations where a lot of deals will be made.

AMANPOUR: So, Minister Abdullah, what has brought you to this point? Because it’s been incredibly difficult to bring both sides to any kind of

peace negotiations? Why are you even accepting to do this?

ABDULLAH: OK. I’ll tell you why. For the sake of our population who is suffering from a lot of things and for the sake of our citizens. For the

Yemeni people we are ready to sit on the table to relieve them from all these things that are happening to our country.

AMANPOUR: There seems to be lots of different factions in the Houthi movement. You are sounding reasonable right now. However, the leader of

the Houthi movement wrote an op-ed in “The Washington Post” a few weeks ago Mohammed Ali al-Houthi. He said, “The United States calling to stop the

war on Yemen is nothing but a way to save face after the humiliation caused by Saudi Arabia and its spoiled leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman

who has ignored Washington’s pleas to clarify Khashoggis murder. Moreover, Trump and his administration clearly prefer to continue this devastating

war because of the economic returns it produces. They drool over these arms sales prices.”

That’s quite fiery. That puts the United States with its back to the wall. Of course, it does support the Saudi coalition. But just lay out your

position on the United States right now.

ABDULLAH: Let me tell you something first. I’m the foreign minister of the national salvation government in Sana’a. It’s composed of two parties,

the Ansarullah, the Houthis and their supporters and GPC, General People’s Congress party and their supporters. We are trying to bring peace to our

population.

So, peace for the people of Yemen, not only peace for these parties. And when you speak about the U.N., about the United States, still we do believe

the United States, as a country, is a peace-loving country. I lived in that country for some time and I know it. We are not talking about the

administration. And sometimes we try to come on approach, the Americans. We try our best.

But today, if you read what the Secretary of State, Mr. Pompeo, article that was published I think in the “New York Times,” what you’ll hear from

Mr. Mattis, the Secretary of Defense, and Mr. Pompeo on his article are two different things. These guys are trying — in fact, the secretary of state

are trying to fight Iran and our territories. Why don’t they go to Iran? Why should the United States play this role of fighting Iran through the

Saudis in Yemen?

We need Yemen as Yemen we need the U.S.’s good efforts to bring peace to Yemen, not to encourage the Saudis to do more and more for this proxy war

fighting Iran in Yemen. That’s my position.

AMANPOUR: Well, let me — OK. And you mentioned the article that Secretary of State Pompeo wrote. It was actually in the “Wall Street

Journal.”

ABDULLAH: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Yes, it was today, in fact.

ABDULLAH: Oh, sorry. On the “Wall Street.”

AMANPOUR: Exactly.

ABDULLAH: Yes, it was.

AMANPOUR: Easy mistake to make from all the way over there in Sana’a. Tehran, it says, is —

ABDULLAH: Sometimes. Yes.

AMANPOUR: Pompeo says, “Tehran is establishing a Hezbollah-like entity on the Arabian Peninsula. A militant group with political power that can hold

Saudi population centers hostage as Hezbollah’s missiles in Southern Lebanon threaten Israel.”

So, in other words, they are viewing you as Iran’s Hezbollah-like proxies in Yemen with a direct — being a direct threat to their ally Saudi

Arabia. What do you say to that?

ABDULLAH: I deny that. I can say, if Iran is doing something the Americans should know. What Nikki Haley provided at the Security Council

in terms of Iranian intervention in Yemen, those ballistic missiles, I can tell you, Christiane, these missiles, we have them a long time ago from the

Russians. We improved them to defend our self.

The Iranians did not bring any missiles to Yemen. And I tell the whole world, we have missiles that can fight the Saudis for years. So, again,

when they want to find the reason, they say Iran is doing the work of Hezbollah in Yemen. No. The reason I say no, why we are going for peace

talks, why we are going to share in any new government, why are we going to do all these measures to build trust, to release the prisoners, to reopen

Sinai Airport, to do all these things, we are not the story of Hezbollah that the American administration now is trying to spread all over the

world.

I think the current administration is really — they have their own problem with this Iranian issue and they did not try to solve it except to go to

Yemen with the Saudis. If the Saudis and the Americans are that great, the Strait of Hormuz is there, the officials are there, they can stop

everything that comes to any country in this region through that place, not to come and bombard Yemen for four years.

AMANPOUR: Can I just ask you, are you really denying that you, the Houthi movement, gets absolutely no support or material help from Iran?

ABDULLAH: As a coalition, actually, we, the CPC, have a coalition with the Houthis or Ansarullah. I can tell you that we are not getting any support

from Iran. If anyone has the documents, the satellite pictures, anything that proves that, let them show it to the world, not to go and say there’s

a scud missile, which we got from the Soviet Union a long time ago and we improve them and try to prove to the world that these are Iranian’s

missiles going to Saudi Arabia.

We did not — Ms. Amanpour, we did not shoot at the Saudis for two years, waiting for something to happen and until we found that no one is listening

to us, we started to defend ourselves. Our arsenal is a defensive one, not for attacks against any country. And we are here in Sana’a, come to us,

we’ll show it you.

AMANPOUR: OK. One other question. As I said, there are many different factions and perhaps competing factions amongst the Houthi population. Are

you saying that none of the Houthis get support from Iran?

ABDULLAH: If the — one of these factions that you say are getting or is getting something or those revolutionary guards in Iran are doing

something, explain them to us, show them to ask. If everyone will just continue to say the Houthis, Iran, Hezbollah, we will not reach peace,

let’s reach peace, let’s go there, build measures for trust and start dismantling many militias in the south and in Marid (ph).

We are only one military or, let’s say, fighting party, which is Ansarullah. The other guys they have 10 to 15 different militias and no

one can control them. Here, we can control our people.

AMANPOUR: OK. Now, let me ask you about the United States. Because as we’ve discussed, the United States backs the Saudi-led coalition and there

have been bombings, definitely all over Yemen, including a very painful one that happened, this is just one of the many that made headlines in the

summer where 44 children were killed, it was the infamous bombing of the school bus and the “New York Times” has written that this site has now

become something of a shrine on a brick wall near the crater, large painted letters, both in English and Arabic which says, “America kills Yemeni

children.”

What is happening now on the ground, because they say they found, you know, American markings on the shrapnel? What is happening on the ground when it

comes to how Yemenis view the United States?

ABDULLAH: Let me tell you first, there are many shrines in Yemen. There are many places that were bombed and hundreds were killed. One here is in

Sana’a, very close to us. And in that place, about 599 people were killed. And this big hole, what you mentioned, is just a small example of these

kinds of massacres that happen to our people.

We are not saying that we cannot speak with the Americans at all. We are not talking about this big continent called the United States of America.

But the administration now is really siding with our enemy who is killing us, they are providing them with information, intelligence. As they say,

precise targeting of these places where they can bomb.

So, again, we are asking the Americans, prove it to the world that you want peace, try to stop weapons coming from — to Saudi Arabia, trying to

mediate in a very good manner by which you don’t side with the Saudis because they are buying weapons from you or providing oil or whatever.

We don’t think about America as an enemy. I quote it again. When we speak sometimes some slogans death to America, we mean the administration, those

who are killing us, those who are providing the weapons, who provide the fuel, but we love the American people. This is a continent, it’s a small

person that you can curse or you can hate.

AMANPOUR: So, then, let me ask you in direct response to this bombing of that particular bus in August. President Trump was asked just recently

about it and he said it’s because the Saudis do not know how to use advanced U.S. weapons. And I’m going to quote, “That was basically people

who didn’t know how to use the weapon, which is horrible. I’ll be talking about a lot of things with the Saudis. But certainly, I wouldn’t be having

people that don’t know how to use the weapons shooting at buses with children.” What is your response to that?

ABDULLAH: With due respect, the president, from time to time, changes his tone towards the Saudis. So, again, these guys are doing things with the

advice of American intelligence information. This place, they work through computers. They are not working to get through the Saudis.

So, you specify the target, you’ll look it, then you shoot. So, again, this kind of justifications are not accepted by us. If the Americans want

to fight the war for the Saudis, to do exactly what they want, then let them come but not blame the Saudis.

Again, I blame the defense department, I blame the military of the U.S. for what they are doing and they are encouraging the Saudis to train on us, on

our population. Enough is enough. Stop this kind of war. The only country in the world that can stop the war, and I say it in front of the

whole world, is the United States not the United Nations. It’s the U.S. who can stop this war because they are the strongest backers of the Saudis.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, now let me see whether you accept any responsibility for what the Houthis are doing. Not long ago I had an interview with David

Beasley, he is the head of the U.N. World Food Program who is responsible for trying to alleviate at least some of the humanitarian burden.

And when I previously interviewed him, he was very harsh on Saudi Arabia and what they were doing around the Port of Hodeida. Now, he’s saying that

he’s pretty angry with what the Houthis are doing, particularly around the port, particularly in holding up and threatening the flow of supplies.

Now, here’s what he told me just a few days ago.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DAVID BEASLEY, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, WFP: Being hard on the Houthis because they don’t provide the access we need, they deny us the visas and the

equipment that we need for the personnel to deliver the food assistance in the different regions throughout Yemen. The Saudis have been more

cooperative. The UAE has really been remarkably cooperative in working with us in terms of humanitarian financial support and access.

And here’s what deportable, when I left that — literally, two days after I left, we found inside our Red Sea mill grain silo what are the type of land

mines that Houthis have been using, and this is in a Houthi controlled area. We had seven landmines inside our facility, inside the grain bins

that were placed there just in the past few days. They have been entering into our facilities, violating every humanitarian principle, putting our

people that are working their lives on the line and it’s got to stop.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: That is a serious accusation. And as you know, just as well as I do, using humanitarian supplies for military purposes like using —

seeding them with landmines is a violation of international law.

ABDULLAH: I saw this interview that you had with David Beasley and I met him personally in Sana’a. First, there were some problems and I do admit

with the pursuit just to get visas, to get other equipment and we, the National Salvation Government, have done all things required now to get

everything required by all these organizations, UNICEF, WFP and others.

Now, about the mines. I speak mainly about the mines after I saw your interview with David. I personally went to the defense department, I went

to the guys who are in Hodeida. and I found out — of course there are now — now doing some investigation. We did not put those mines and we

won’t — we requested the U.N. to give us the pictures of these mines to say if they are ours or they are the other party who put them inside that

mill.

Why didn’t they tell us after they returned back from Hodeida about this? We will investigate it. But now, I can tell Mr. David Beasley that we are

investigating this and we are writing a full report to him, to WFP and we are going to prove that these mines are not ours. Why should we put mines

in the mill that is feeding our people, in Yemen? Why should we do it?

AMANPOUR: But he also said, and you heard, that is — that the Houthis down there making jolly hard for humanitarians to come and relieve the

suffering, including the WFP. I mean, that’s got to stop.

ABDULLAH: We are going to stop it. We are open to all U.N. comments. Any obstacles, we are going to stop it. As I said, we are trying to help our

population. Why should we make it difficult for our people to get food? There is no rational reason for that.

Again, any things that are being done by any groups who are in that area, there are many groups, we are ready to deal with it and facilitate

everything for the U.N. any — and any humanitarian agency or people doing something for our people who are dying because of this aggression by the

Saudi coalition.

AMANPOUR: Well, I hope the U.N. can rely on this promise from you via our program tonight, because it is for your people and it’s fundamental. You

and your leadership have recently mentioned the death and the dismembering of our colleague, the Saudi journalist, Jamal Khashoggi.

Has his brutal murder by the Saudis — had the — I don’t know, at least, the beneficial impact of focusing attention on Yemen?

ABDULLAH: Yes. It played a big role in this, in getting the crown prince really disarray in different directions, he cannot do many things at the

same time, fighting different fronts. But it really did. It brought the attention to Yemen. And while Khashoggi really died as a martyr in a very

bad occasion, thousands and thousands of Yemenis are dying every day because of the Saudi coalition.

AMANPOUR: All right. OK. And, of course, I point out that Yemen is suffering from what the U.N. calls the worst humanitarian crisis in the

world right now. Foreign Minister Abdullah, thank you for joining us from Sana’a in Yemen.

ABDULLAH: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: And as always, we have asked for Saudi officials to come on our program to respond and we will continue to ask.

Coming up on this program, my conversation with the actor, Willem Dafoe, who plays the artist Vincent van Gogh. His Lashon floral landscapes come

to his tortured soul.

But first, the picture painted of the online world is not always pretty, trolls and keyboard warriors. We’re advised to ignore the haters, but our

next guest decided to take them on.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DYLAN MARRON, HOST, “CONVERSATIONS WITH PEOPLE WHO HATE ME”: Hi. I’m Dylan Marron. And I’m starting a new podcast called “Conversations with

People Who Hate Me.” It’s an interview series where I get to know some of the people behind the negative and hateful of messages I’ve received on the

internet.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

The point in Dylan’s words, remember there’s a human on the other side of the screen.

Dylan Marron a writer, performer and digital creator, examining the tense interface between race, sexuality and privileged. He told Alicia Menendez

why he believes empathy is not indorsement.

ALICIA MENENDEZ, CORRESPONDENT: So, here’s a part of your story that I have never gotten a clear answer on, which is —

MARRON: Right.

MENENDEZ: — you’re trained as an actor but you’ve really made a name for yourself making digital videos that are much more and acted as they. How

did you make that jump?

MARRON: I was an actor all through high school. I got to college, I joined a sketch comedy group and I loved it. I loved this idea of working

with a group to satirize your community, to write stuff for yourself. I think from there, I start — I wrote a full-length play with a friend of

mine. We got some opportunities to perform it here in New York. I joined a theater company called “The New York Neo Futurists.” Here, I was with

them for four years.

And then, with all the stuff I was doing there, I was kind of naturally evolving into talking about social issues through my work. So, I wanted to

translate that from the stage to the internet, and that’s what I did.

MENENDEZ: So, then, how did you make the jump from that to social justice videos?

MARRON: Well, so, I guess the first video series I started doing that really took off was “Every Single Word.” It’s a video series where edit

(ph) down popular films to only the words spoken by people of color.

MENENDEZ: They’re short videos?

MARRON: Very short videos, like tragically short. And it’s speaking the language of the internet, right. It is — it’s ultimately a supercut and a

lot of people found it super funny. Of course, through the humor there is also something else being said. These characters are only peripheral, do

these characters have any names, can you understand the story — the larger story of the movie if you only see the lines spoken by these people of

color.

And so, that kind of took off and I realized that the internet was this really wonderful way to talk about very complex issues if you could

challenge yourself to distill it into very — into a more simple output.

MENENDEZ: And for your next series, you put yourself in the video?

MARRON: Yes. The next big series after that is — was in response to the (INAUDIBLE) bathroom bills that were gaining media attention around the

United States. And I wanted to humanize the like very people at the center of this issue rather than just having pundits, you know, like consider

this. So, I started a series called “Sitting in bathrooms with Trans People.”

We talked about super Monday and stuff, you know, like just who they are, snacks they liked. We also talked about things like transitioning only as

long as my guests were comfortable with it. But the main point of it was to just say like hate grows from fear and fear grows from not knowing.

MENENDEZ: My question with that series and then with your series “Unboxing” where you take, you know, sociological phenomenon —

MARRON: Yes, yes, yes.

MENENDEZ: — and really debunk them —

MARRON: Yes.

MENENDEZ: — is, are the people who are scared or are the people who don’t understand this issue the way that you might understand it watching not and

are they being persuaded by that content?

MARRON: So, that was a real thing I had to wrestle with. I think when I was making those series, I truly thought I am reaching all the people that

I need to reach, because you just see a number and sometimes you see these enormous numbers and you see it growing. So, you think that you are

reaching all the people you need to reach and you are think you are drastically changing minds by sharing these truths that are truths to you

on the internet. I quickly learned that was not the case.

MENENDEZ: How?

MARRON: Through comments and messages. And first, with the like deluge of negative comments. I want — I just ran away from it, right.

MENENDEZ: Can you give me a sense of what those — I mean, as someone who has an Gmail folder that’s called hate mail —

MARRON: Yes, yes.

MENENDEZ: — that has lots of mail in it —

MARRON: Yes.

MENENDEZ: — what’s the type of mail that you get?

MARRON: So, just a lot of people calling me a faggot. People disagreeing with my take on social issues and a lot of people telling me I was cancer,

right, that that kind of terminology used to describe people who talk about social justice on the internet.

MENENDEZ: Did that hurt or were you able to just dust it off?

MARRON: It totally hurt. Yeah, it totally hurt. Clearly, I was getting many people from the right who more identified as conservative. But I was

also getting a bunch of fellow lefties and that’s — that was, I think, particularly hard to deal with because there’s a box in your mind where you

can put a comment from someone you are ideologically opposed to, it’s very, very challenging when you get it from someone who is, in most ways, very

similar to you.

MENENDEZ: So, then you make something out of those comments. What is “Conversations with People Who Hate Me”?

MARRON: “Conversations with People Who Hate Me” is my podcast and it’s a show where I call up some of the people who have written negative things to

or about me on the internet and we have an extended conversation.

MENENDEZ: What is your objective with the podcast?

MARRON: The sign off line I always end every episode with is, “Remember, there is a human on the other side of the screen.” And I think my

objective with the show is to remind people of that. And that means, one for the authors of this negativity, of the fact that the person they’re

writing to or about is a human who will maybe read what they have written. But also, for the recipients, to remember that there is a human who has

written this. And —

MENENDEZ: That seems particularly important in the internet age. I mean, you are 30, I’m 35. We grew up on the internet.

MARRON: Yes.

MENENDEZ: So much of our ability to interface —

MARRON: Yes.

MENENDEZ: — with one another is —

MARRON: Yes.

MENENDEZ: — informed by the way we speak to each other online.

MARRON: Yes.

MENENDEZ: I mean, do you think this is unique to the time we are living in?

MARRON: I do, I do. The kind of like monitor I’ve established for myself or the show is that empathy is not endorsement. And what I mean by that

is, just by acknowledging the humanity of someone else does not mean you are immediately cosigning everything that they believe, everything they

think, their political ideology. But I do think it is important to see each other as human.

I’m not saying we should give the most dangerous ideologies room to grow, right. But I do think it is valuable to acknowledge that those ideologies

grow in humans and those humans were once babies, you know, and they were shaped by all of the things that we humans go through in life and there is

value in — only as people feel they have the ability to do so.

MENENDEZ: Let’s talk about the first episode.

MARRON: Let’s talk about it.

MENENDEZ: When you decided to con man named Chris. He had written some hateful messages on a video you posted about social justice. Let’s take a

listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MARRON: So, I don’t want to put words in your mouth, so correct me if I’m wrong. I was kind of like the image of the social justice warrior, right?

CHRIS: Right, right.

MARRON: And how would you define a social justice warrior? Don’t worry I won’t be offended.

CHRIS: To meet, a social justice warrior is a — for the most part, a rich college student who has his parent, mom and daddy, pay for everything and

they pick and choose these subjects to be angry about in a world where people really generally don’t have that much to be angry about.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: What did you take from that conversation?

MARRON: The like real kick in his messages that he had called me a piece of (bleep). And, you know, my take away from that is it is so easy to feel

angry, furious, to feel hate for someone from afar. And it is so hard when you’re on the — it is harder when you’re on the phone with that person,

right. And so the ability to talk to a human who sent me a message like that kind of put me at ease and from or my relationship with Chris, I think

that it put him at ease as well, right.

It’s just — it’s easy to talk about — meaning I’m putting myself in Chris’s shoes, I can imagine it is easy for him to talk about the hate of

Social Justice Warriors, SJWs as we are known on the Internet. It’s kind of more difficult to define that to the person who you’re labeling as an

SJW when you’re on the phone with them.

MENENDEZ: I understand what that means for you and I understand what that means for Chris. What do you think it means fearless? Where does it take

them?

MARRON: Great question. I know that many people listened who have politically divided homes and it gives them a little sense of hope for how

they can communicate with family members who don’t agree. I know others — you know, we do have a good number of conservative listeners too. It’s not

the majority but there are who feel hopeful that this is what conversations can sound like.

What I’m always really, really careful to say is that this is not a prescription for activism. You know what I mean? I’m not saying that

everyone must now call their online detractors and then the world will be a better place.

MENENDEZ: No, in the country, there are definitely activists who take a very different stance than you know —

MARRON: Very different.

MENENDEZ: — and I think have some legitimate concern that by giving a platform to people who come from a place of hate in some cases, who come

from a place of extreme bias that even you often say empathy is not an endorsement but I do wonder if it is legitimization.

MARRON: Well, currently in this moment, I really do believe that conversation is crucial to have. I did not invent these dangerous

ideologies. I also don’t believe that by ignoring these dangerous ideologies that you are doing any service to understanding nuance and

complexity of what it means to be human.

I also know that if that quote is then taken out of context, then people will apply it to what they believe to be the most dangerous thing. And

then I think it’s, of course, a little misleading that the word hate is in the title because what I’m referring to is the kind of innocuous hate, hate

that is written online every day that we see our friends write.

MENENDEZ: In addition to speaking to people who have given you negative comments, you also bring people together. In one episode which we’re about

to listen to, you bring together Emma Sulkowicz, a rape survivor who was very public on Columbia’s campus with Benjamin, a person who has called

Emma a liar.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MARRON: The reason we’re here and the reason we’re on this call is that Benjamin, a few years ago, you wrote Emma a message with very few words.

You just said, “You are a liar.” Emma, how did it feel to receive it?

EMMA SULKOWICZ, RAPE SURVIVOR: Honestly, it wasn’t even just Benjamin’s message individually that hurt so much. It was the torrential outpouring

from the internet of these kinds of messages into my lap.

MARRON: Well, I apologize for the hurt. I do sincerely apologize for that. I know it might sound trite. That wasn’t my intention but I don’t

apologize for the disagreement. You became a very public person, right. And you didn’t — from everything that I could see, you didn’t shy away

from the public eye either. Maybe some messages should be expected. And I didn’t — you know I would never say like any death threats or anything

like that. I’d never do that. I hope that on the spectrum, it was a rather a benign one.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: You’ve said this is one of the most challenging episodes that you’ve done. What about this was challenging for you?

MARRON: Well, this is taking a conversation online that is incredibly difficult and trying to give it space to breathe offline. We are seeing,

you know, with a movement that I fully stand by as an ally which is the Me Too movement, we are seeing a lot of survivors bravely come

forward as being survivors of sexual assault.

And when we have these conversations online about the importance of believing survivors, that’s one thing because I think we are — and because

we have to, we’re using talking points and we’re using hashtags and that is crucial for online communication. What’s complicated is when you get

offline. And, you know, this was — and this is a very specific case, meaning I think it’s important to only speak about the specifics of the

dynamics between these two people, Emma and Benjamin.

And Emma, you know, Emma was thrust into the public spotlight and then a stranger who found his way into Emma’s is inbox with a message that said,

you know, “You are a liar”, I think what we’re talking about here is the disbelief that some people have when rape survivors come forward. And the

demand for forensic evidence when that is itself an incredibly complicated topic.

I think this was challenging because my job is to make sure that all the people on the call feel safe. I needed to make sure that Emma felt safe

talking about this. And also if Benjamin didn’t feel comfortable with how the call went, the episode wouldn’t have gone out. But I think my job is

creating a safe space for all of my guests including Benjamin and —

MENENDEZ: Is it your job to hold them in equal weight?

MARRON: Well, I don’t know that it’s important to hold, one, a human’s account of what happened to them in equal weight to a stranger who’s

denying that that ever happened to them, right. A stranger’s suggestion that what they say happened to them didn’t happen. I don’t think it’s

about holding those two things in equal weight.

But what I do think my job is, is holding the fact that these are two human people, two human people who were once born, you know, and went through a

whole bunch of experiences and communities that shaped who they are today. And that is what has caused them to intersect on my show.

MENENDEZ: Thanks so much.

MARRON: Yes. Thanks for having me.

AMANPOUR: A rational and human approach in an online world that’s often anything. But now to an artist whose paintings are among the most rational

human and recognizable in the world, his style is so distinctive that he is undoubtedly one of the first artists any child could recognize.

This, in Van Gogh’s story of struggle and mental illness, is among the most well-known. Who would take on the challenge of portraying such a towering

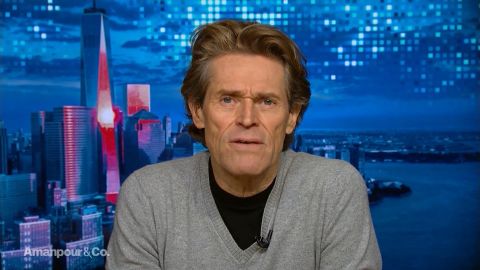

figure on the silver screen? Willem Dafoe, of course. From art-house to blockbuster to tune to Spider-Man to the Florida project, Defoe has done it

all and he’s been nominated for a few Academy Awards along the way. His new film is “At Eternity’s Gate” and he tells me that he not only learned

to portray the old master but to paint like him too.

Willem Dafoe, welcome to the program.

WILLEM DAFOE, ACTOR: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So first and foremost, I struck me that you look exactly like Van Gogh in the film. I mean you just to. Did you really absorb him?

DAFOE: Well, I tried to inhabit him. As far as looking like him, I never saw it particularly. You know, he did so many self-portraits and they’re

quite different. There are different stages of his life but no. I — after the fact, I mean I felt like him.

AMANPOUR: Yes, yes. And he is an intense human being. Van Gogh has been depicted every which way. There are at least five movies that have been

told about him, endless exhibitions. There are — his work is just so phenomenal. And is — you know, hundreds of millions or tens of millions

of dollars every auction piece that comes up. What made this one different for you? What — why did you agree to do this?

DAFOE: This film, primarily because a painter was directing it, a painter that also happens to be — I’m a great filmmaker, he’s a great painter.

I’ve known Julian Schnabel, the director of the movie, for a long time. I’ve been in his studio while he’s working. I’ve worked with

him in minor ways on some of his movies. I knew that I would have to learn how to paint in this movie and he was going to be my take teacher. So that

was drilling.

And it’s not a traditional biopic. It really concentrates on what he does. Often with movies about historical figures, they — usually what they do is

kind of a given. And then they concentrate on some sort of interpretation of their psychological makeup. I think this just really concentrates on

the work, on painting, on being an artist. We rely very much on his letters and also painting.

AMANPOUR: Well, as you say, Julian Schnabel said I didn’t want to make a movie about Vincent van Gogh. I want to make a movie where you Willem

Dafor were Vincent van Gogh.

DAFOE: Yes. I think the way the movie is shot, the way we approached it is we wanted to find out what — we tried to imagine what it would be like

to be with his thoughts and be with him doing the things that he did.

So we shot in the actual places he were. I was painting. The approach was not so much an interpretation as, you know, a desire to inhabit or imagine,

have the audience be with him. It’s a very subjective camera and you’re with him all the time.

AMANPOUR: And that is absolutely clear throughout. As a viewer, I really did feel that. But tell me because it is remarkable how you were taught to

paint by your painter director Julius Schnabel.

DAFOE: Well, you know, he starts me out as you would think, you know, with very basic things, how to hold a brush, how to apply paint, how to mix the

paint, how to keep things in order, all those sorts of things. Basically technique craft things.

But I think more significantly, he really shifted how I see. He talked to me a lot about making marks and the accumulation of marks and marks talking

to each other, to create a swirl that really expressed what you see. He also taught me that you don’t rush to represent something. You really see,

you try to paint what you see.

So when I’m painting a cypress tree, he really encourages me not to think about representing, doing a good likeness of the cypress tree, but really

painting the light, seeing where the dark spots are, where the colors are, and just thinking about each individual act of making that mark. And then

they accumulate and you actually see it in the movie, in the sequence where I paint the shoes in real time. You see how all these marks that don’t

really look correct all of a sudden transform the painting into something that may not be necessarily a good likeness but really captures what you’re

looking at.

AMANPOUR: Yes. I was going to say that actually. And that is you painting it from beginning to end?

DAFOE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Wow.

DAFOE: I mean often, you know, for example, that sequence, I was very well coached on and I practiced doing that because I knew I was going to do that

more or less in real time. You don’t see it in real time because that would be tedious maybe. But to do it — to shoot it in real time without

traditional coverage really made it more organic, agave, and integrity. Because you do see that shift from a series of marks in a swirl of colors

into something that does speak to those shoes that I’m looking.

AMANPOUR: So fast forward in the movie and you are painting a portrait of the famous Dr. Gachet I think his name is.

DAFOE: Right.

AMANPOUR: And we’ve chosen a clip from that and it’s sort of, you know, a kind of amplification of what you’re saying right now about what the

painting means and how you felt during the film. Let’s just play this moment.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

VINCENT VAN GOGH, PAINTER: When I paint, I stop thinking.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: About what?

GOGH: I stop thinking that feel that I’m a part of everything outside and inside of me. I want so much to share what I see.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: I mean it’s very very moving because you know that Vincent van Gogh is a tortured soul and seems to have a hard time communicating. Those

scenes in the film where he’s really — you can understand why he’s being bullied, why his, you know, kids are throwing stones at him, why people are

destroying his paintings. Tell me about that, about what that little clip says about him.

DAFOE: He had a gift and he had a vision but how to reconcile the joy and the connection with that with, you know, daily life was

difficult for him. Socially, famously, it’s really chronicled in his letters, had a hard time with people and people — he was a difficult

person socially. He had problems with women. He had problems with the people in the town. He had problems with the whole art market.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And we don’t question why. And again, there’s this amazing scene where you as Vincent are committed to I guess an insane

asylum and his brother Theo who’s also an art dealer comes to visit him. We’re just going to play that.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

THEO VAN GOGH: Why did they put you here?

GOGH: (INAUDIBLE)

GOGH: There must be a reason.

GOGH: (INAUDIBLE) You’re right. I’m losing my mind. You’re suffering right outside of me until it goes out of me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So tortured soul. Where do you come down on what his problem was?

DAFOE: I think the, you know, he knew a certain kind of ecstasy and knew a certain kind of joy through his work but he couldn’t reconcile that with

daily life.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

DAFOE: And as indicated in the other clip, when he was painting, somewhat, you know, you relate to this — you know, when you feel connected to your

work, when you’re in the zone, when you’re in the flow, you feel well. And when he was outside of that zone, I think he felt very lost.

AMANPOUR: And it is extraordinary to remember that apparently, he sold almost nothing when he was alive.

DAFOE: Right, right.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

DAFOE: But people were — to be fair, people toward the end of his life, people were talking about him. He got some very positive reviews so it may

have been a matter of time before he started to sell. But I think he made a huge leap. He had took a huge break from what was fashionable at the

time. And anytime that happens, I think it takes some time to catch up.

AMANPOUR: So Willem Dafoe, you have a quite extraordinary prolific. You are as prolific as van Gogh. I mean you’ve done so many films, 99 I think.

I think this one is your 99 film and you’ve done everything from sort of art house to blockbuster.

And, in fact, in one of the articles I read about you, it said that you could do an art house film, enable Ferara (ph) or whatever it is but then

you had to swerve back to Hollywood. You had to do a blockbuster or a Disney or something to keep yourself, you know, marketable. That’s what

the system demanded. Is that what you find? Or are you enjoying doing all of this variety?

DAFOE: That’s part of it but I think the variety helps because it keeps you from getting stuck. I always appreciate — you know, performing is a

thing that can be approached from many different ways, making things as a thing is an activity that can be approached from many angles. And I think

your way of doing things gets challenged, you exercise different muscles.

I noticed certain patterns of things that I’m drawn through to. For example, I’m very drawn to very strong directors, whether they’re in an

independent cinema or studio movies. I like to basically mix it up. It feels healthier. There is that career consideration somewhat but that’s

not foremost. I say it’s more really an artistic choice that you don’t like to get stuck. You don’t want to keep on going to the same instincts.

You don’t want to keep on going to the same well.

I think to keep it loose is to be free because you’re always working from the beginning when you start a project because you have nothing to compare

it to. There is nothing normal. There is nothing regular. So as long as you stay out of that kind of routine, I think you’re free and you’re more –

-you can access the imagination and desire to find things out curiosity and wonder much more easily.

AMANPOUR: You come across as a bit of an iconoclast, a bit of a sort of a rebel.

DAFOE: Fooled you.

AMANPOUR: Yes, exactly, exactly. I was going to say. Because you come from an incredibly normal, middle class, a professional family from

Wisconsin if I’m not mistaken. I think your father was a doctor.

DAFOE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And your mom?

DAFOE: She was a nurse —

AMANPOUR: There you go.

DAFOE: — who worked with him.

AMANPOUR: And you — and so start with that because you have many siblings. A lot of them became nurses and you talk about how your siblings

sort of raise you because your parents were often out working and out all hours. What was it like growing up in that household?

DAFOE: It was a big family. I was toward the end of it. I was brought up by my sisters. My mother was the original super mom but she really was

true — truly more a career woman. She worked with my father. They both were workaholics.

And I think from that experience, I saw that it worked very well for them. And I think I always seek — I tend to work with people that I love. I

like to work. Growing up, it was chaos. It was chaos but it gave me a lot of freedom and it’s not bad being raised by older sisters.

AMANPOUR: It’s not bad at all. You’ve done, I mean obviously, so many but Platoon and Mississippi Burning and, of course, you know, The Florida

Project which you were nominated for. You played a really sweet person in The Florida Project. You were really there to help these people who are so

down on their luck. What kind of roles do you like playing the most? Because, obviously, the difference between Platoon and the hotel manager in

Florida Project is massive.

DAFOE: Simply, I like the idea of being transformed. You know, learning something and taking a point of view that I didn’t know before. For

example, when I played in the Florida Project, I had no idea that that was a sympathetic character.

I really was — I’m not that attracted to characters because you don’t know what they are until you do them. I’m attracted to situations and in that

situation, I knew the filmmaker. I knew we’re going to film in a real motel. I knew we were going to mix non-professional with professional

actors. All those things interested me.

So I think it’s really the project and the people that I’m drawn to. And as far as characters, I think if you can identify their function or what

kind of people they are before you even begin to inhabit them, then that discourages you from surprising yourself or being transformed or learning

something. So I think I have a nose for adventure and curiosity and sometimes that bites you back because you never answer your questions. But

it’s best to start out with questions rather than have an idea and have your job be expressing or executing.

I like to feel like every time is the first time. And, of course, that becomes ridiculous when you’ve made as many movies as I do. But somehow

there’s something in me that I’m able to do that. I’ve got a certain kind of amnesia.

AMANPOUR: Or a gift. I mean because that is the gift that you give to the audience really that you come at it, you know, with this energy and this

passion every time. Will you continue painting do you think? Have you found a new hobby or a new love?

DAFOE: You know, I love painting. But the truth is I’ve got a pretty nomadic life and I think to really paint in a serious way and pretty much

when I do something, I do it seriously, it’s hard to bring your studio with you. And also it has to be a daily practice. And I have enough other

practices that I have to do. And when you’re working 12 hour days on a movie and working every day, it doesn’t allow much time. So I’m foremost a

performer and I better stick to that.

AMANPOUR: Well, Willem Dafoe, thank you very much indeed.

DAFOE: Thank you so much. Nice talking to you.

AMANPOUR: You too. So Willem Dafoe there on becoming Vincent van Gogh. It’s a performance that could lead him to us to glory next year. “At

Eternity’s Gate” is in movie theaters now.

That’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow.

END