Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Mass population flows and refugee crises are another major national security concern facing Western countries. And our next guest, the immigration lawyer, Becca Heller, has been on the front lines fighting against President Trump’s travel ban on predominantly Muslim countries. Winner of the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant for her work protecting refugees in the U.S. from deportation, Heller has been speaking to our Alicia Menendez about her ongoing mission to represent displaced people and immigrants in the Trump era.

ALICIA MENENDEZ: Becca, thank you so much for joining us today

BECCA HELLER, CO-FOUNDER, INTERNATIONAL REFUGE ASSISTANCE PROGRAM: Thanks for having me

MENENDEZ: So, our domestic conversation around refugees has focused largely in the recent weeks and months on migrants coming from Central America. But before that dominated headlines, there was the so-called Muslim ban, you were corralling resources to act at their disposal. Can you take me back to that moment?

HELLER: Yes. I mean, one thing that’s worth pointing out is that there is still a Muslim ban, so-called or not so-called, it’s still in place. It’s preventing millions of people who otherwise should be eligible to come to the U.S. and reunite with family members or get critical treatment for diseases from coming in. I think it’s been lost in the narrative shuffle quite a bit, but it is it is currently being enforced and keeping out tons of people all the time. When the first version of the Muslim ban — because now, we’re on version, you know, 3.5 or 4.5, depending on how you count, came down, my group, the International Refugee Assistance Project, organized all the lawyers who went to the airport to try to make sure that people weren’t illegally detained and deported and we were, you know, I think largely successful in the first few days at preventing kind of large scale deportations under the ban.

MENENDEZ: Can you draw a line for me between the crisis in Central America, the Muslim ban and explain how these two stories fit together?

HELLER: I think that you have an administration that, for whatever reason, has decided that the heart of its policy is going to be the xenophobia and that the best way to rally support for whatever affirmative policies they want to hatch, which has yet to be seen, that the best way to generally rally support for that is to discriminate against immigrants. And I think that, you know, those immigrants tend to predominantly be from, to use the words of our own president, — countries and that’s who’s bearing the brunt of this and that’s countries in the Middle East and North. Africa and that’s countries in Central America and it may start to be other countries as well. But I think it’s mostly countries that produce a lot of refugees and forced migrants trying to come to the U.S., I think it gets defined backwards. Basically, if you’re trying to get in, we don’t want you.

MENENDEZ: What is the biggest misconception about refugees?

HELLER: Oh, there are so many big misconceptions about refugees. I mean, I think, you know, the right and the left each have their own set of misconceptions. I think there’s a series of misconceptions on the right that, you know, refugees are terrorists, that refugees take American jobs, that refugees are a strain on the economy. I think there’s similarly a set of misconceptions on the left that refugees are sort of these needy helpless victims and that the reason to take refugees in is that we have some sort of like moral obligation to help them as they’re like strong international brethren, and I think that that’s sort of like equally ill-conceived.

MENENDEZ: There’s been a lot of attention on this question of family separation in light of the Trump administration —

HELLER: Right.

MENENDEZ: — policy of separating children from their parents at the border. And yet, there is this lingering question of whether we, as a country, believe in full family reunification and whether or not that should be a priority of our immigration system.

HELLER: I think that most immigration policies in most, you know, so- called like democratic countries focus on bringing families together, like the core of any immigration system is that if I’m here and I have family who somewhere else that I should be able to bring my family here so that we can be together. I think that part of why people were able to get so activated around the issue at the border is that, you know, they were able to go witness it, right. It was not dissimilar to the situation at the airports where, you know, you could go to your local airport and be with a mass of people and sort of — not that you could see people detained but you could see the airport is sort of the symbol of what was happening. And journalists were able to get photos of kids in cages and kids being separated from their parents. And it was that kind of imagery and access that made it possible to have such a visceral reaction. Whereas, if families are still separated as opposed to if like the U.S. is actively separating them, it’s much harder to document in a way that gives people that visceral reaction.

MENENDEZ: For example, the Yemeni mother who was able to finally visit her dying son in the United States, I mean, that story didn’t get nearly as much attention as what is happening on our Southern border.

HELLER: Yes. But I think — so that — in that case, there was a there was a two-year-old Yemeni boy, and I believe Oakland, who was dying and his mother couldn’t come be with him because of the Muslim ban. She applied for a visa to be with her dying son and she was rejected, and that is actually illegal even under the terms of the ban itself. Because the ban says in exceptional circumstances like if your — and it doesn’t spell out this precise circumstance but it gets awfully close, if you’re a mother and your kid is in the U.S. and dying, we will make an exception. We will give you a waiver and say, “Yes, you can have a visa and you can still come in,” and they didn’t do that for her. And part of the reason for that is that there is no real waiver system, and that’s something that’s being challenged in courts right now. But I think, you know, there were three straight days of headlines in a lot of newspapers saying this woman should be able to come in. And one thing that really struck me is that I think it’s pretty unusual for there to be three straight days of headlines about Yemen that aren’t talking about like terrorism or famine or civil war or drone warfare, et cetera, they were literally just talking about this mother who needed to be with their child. But I think, also, the reason that it ended quickly was that it only took three days of public attention for the administration to just completely reverse itself. It didn’t take a lawsuit. it didn’t take an act of Congress, it was just three days of public outcry and then they turned around and they gave her her visa. And I think in the case of child separation, it was the same thing, where, at the end of the day, the administration reversed itself, at least publicly, we’re now finding out that privately and, in fact, did not reverse itself very much, that there are thousands more children that were separated from their families that we even know about. But, you know, publicly the administration reversed the policy simply in response to like a massive public outcry but it still took weeks and weeks of newspapers, just relentlessly covering it and people going to the border. But in the end, you know, the public outcry worked.

MENENDEZ: You often say that your work is apolitical and I wonder to that end if you can cast —

HELLER: Yes. Don’t I find apolitical right now?

MENENDEZ: — a retrospective critical eye on the Obama administration, when he himself was called deporter-in-chief, when you look back at the policies of that era, in what ways have they softened the ground for the policies that we’re seeing now?

HELLER: Yes. Obama deported more people than any other president before him. and I think — you know, I don’t have the statistics at my fingertips right now, but I think, you know, in the first year or two of the Trump administration, he still wasn’t supporting as many people as Obama did. And, you know, things like the use of tear gas on the border, the, you know, mass detention of children on the border, like these were not things that began with Trump. These were things — and they weren’t things that began with Obama. You know, they were policies that Obama continued. Like we — we’re not great with immigrants in this country. We have a long history of treating immigrants pretty badly dating back to before the Revolutionary War really. So, I don’t see the mistreatment of immigrants as a partisan issue or even necessarily as a political issue. I think it’s been hijacked as a political issue like —

MENENDEZ: So, then, what would it look like to get this right?

HELLER: To get immigration policy right? I mean, I think families should get to be together. I think that you can’t look at immigration policy in a vacuum, right. I think if you’re talking about policy on the southern border, you can’t talk about that without a discussion of like what is our economic and foreign and military policy in Central America. And I think all these questions about like how many people should come over the border and whether the border should be open or not, like it’s sort of missing the larger context of the role that we’re playing in creating a migrant crisis in the first place. If our economic policies are creating dependent economies where there are no jobs, I don’t think we should be very surprised when people leave those economies and come here looking for jobs.

MENENDEZ: It does for many people come down to this fundamental question of how many people should be allowed to come into the United States. How do you sir that practical question?

HELLER: That’s just not how our current immigration policy works even. Like a lot of the — a lot of our sort of vectors of immigration policy of how people come in don’t have caps. So, even the status quo, like the way that we designed the immigration policy isn’t based on this idea that like a certain number of people should be able to come in every year. And if it were, you still want to look at like what types of people are coming in and balancing that, right. Because, for example, like a lot of spaces are reserved for people to come in and like be doctors at hospitals, which is something that we really need. And, in fact, like since the travel ban and since the crackdown in immigration policies there have been a bunch of articles about how hospitals, especially in like sort of the Rust Belt area, can’t get enough doctors and nurses to come in because people don’t want to come work here. Similarly, with like H1Bs, that’s for people to come work at tech, we’re losing a lot of people who are going to Vancouver instead of to California now because they don’t want to be in the U.S. So I think it’s not — you can’t look at it as just one number and say like the U.S. should take in 2 million immigrants a year because a lot of it should be about like determining both the needs of kind of immigrants to come in but also the U.S. really needs immigrants. Like we need people to come in and help with agriculture. We need people to come in and study. We need people to come in and just make our country a more sort of, you know, urbane, cosmopolitan, diverse place.

MENENDEZ: This question of refugees, resettlement, displacement is a global question at this point. Looking at this globally, what is the greatest challenge facing refugees in the work that you do?

HELLER: I think the greatest challenge facing refugees today is that they’ve been hyper-politicized by the sort of outright movement all over the world and made scapegoats. And so, you know, people are really afraid to let them in. I think in the U.S., across Europe, you know you have elections being decided on refugee policy. Like you can look at Germany and see sort of the rise of the Minister of the Interior over Angela Merkel and say that’s about refugee policy. And you can look at the rise of far-right governments in certain Eastern European countries and say that’s about refugee policy. I think that’s really hard to contend with and it prevents a lot of forward movement. I think everyone agrees, no matter where you sit on, you know, pro-immigrant, anti-immigrant, close the border, open the border, like everyone agrees that the system is broken. But I think as long as we’re in this sort of hyper-politicized hate-filled, blame-throwing environment where we like can’t even sit down and have a rational conversation, it’s going to be impossible to change the system one way or the other. And I think that’s the biggest challenge today. I think the biggest challenge in two years is climate change. I think that the, you know —

MENENDEZ: In the sense that it displaces people.

HELLER: Right. I think the most immediate major effect of climate change on like my generation is going to be that certain places aren’t going to be inhabitable anymore, right. Islands will be underwater or people who live in desert, it will be too hot to live there. Places will become ravaged by disease. None of those people fall under the traditional guidelines of what it means to be a refugee because those were written after World War II with a very specific political situation in mind. And there is no plan for how to deal with this. And I think that’s a really big issue that the whole world is going to have to deal with because people are going to end up somewhere. Like if your island is underwater like you’re going somewhere. And I think we need to start really seriously thinking about where that is and how you can get there in a safe way that doesn’t involve like a raft or traffickers or smugglers or coyotes, you know, are being turned back by Interpol.

MENENDEZ: This started, you were a law school student, right? 2008. I’m sure you did not imagine that this would become what it has become. You have been honored with a MacArthur Genius Award. What is it about your work that makes it so unique?

HELLER: I mean I think a lot of things about our work make it really unique. I think one is sort of the legal angle. You know when I first started — I’m really obsessed with the fish and sea and I was not interested in starting an organization. I think a lot of people go to law school because maybe they don’t know what else to do. I went to law school because I wanted to be a lawyer. And as it turns out, when you’re running an organization, you’re not really lawyering at all. And so I spent the first year just trying to figure out like who else is doing this because it seemed kind of obvious to me, you know, your big problem is legal. Like if you’re in Syria and you’re going through like a hearing that’s going to determine whether you get to leave Syria and go to Canada like you’re basically on trial for your life, right? What do you need the most? You need to make sure that trial is fair and you need to make sure you have a good lawyer. Like if I was on trial for my life, that’s what I would want to. And it took over a year to just kind of realize that no one was doing this. I think we have this really unique model of engaging law students and lawyers all over the world to use technology essentially to provide representation to refugees and places where ordinarily they wouldn’t be able to get it. And then I think our model of combining kind of direct legal aid for a large number of refugees every year with more systemic kind of advocacy litigation work is a way to take a more like interdisciplinary approach to the problem where we see sort of like where are the individual kinks where people are getting tripped up and then where can we try to go in and fix those. So we’re not just saying, you know, the answer is to let more refugees and then like hammering on that one really broad point. We can say like it is really silly that to qualify for this visa for interpreters from Afghanistan, you have to get an original signature from Kabul to Nebraska. That’s not possible when the Taliban is reading all your mail. Why don’t you just take an electronic copy of a signature? And that suddenly opens the door for 5,000 people, you know. You can sort of take advantage of being like a legal nerd to find like technical fixes in the system that can actually open the door for a huge number of people that just like no one has noticed because they haven’t walked through the system that many times. So I think taking advantage of the fact that we’re huge dorks have been pretty helpful.

MENENDEZ: Becca, thank you so much.

HELLER: Thanks for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

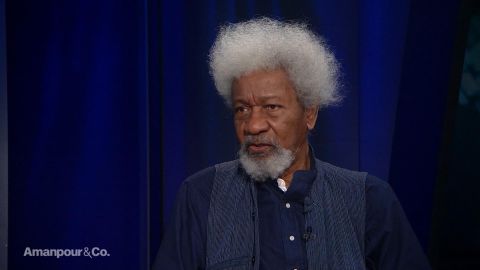

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Richard Dearlove, former Head of the British Secret Intelligence Service, about why ISIS is still a threat: and Wole Soyinka, Nobel-prize willing poet, about this weekend’s election in Nigeria. Alicia Menendez speaks with Becca Heller, the human rights lawyer who took on President Trump’s travel ban.

LEARN MORE