Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

The America’s two disruptors in chief meet for the first time. As Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro heads to the White House. We ask whether heated rhetoric

now prevails over cool diplomacy, and what is the cost. Veteran U.S. Diplomat, William Burns joins me.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR, THEN-U.S. SUPREME COURT JUSTICE: And the reality of it all will only come into focus over time, I think.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, that time is now as we dig into the sometimes-forgotten legacy of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman to ascend to the

U.S. Supreme Court.

Plus, under arrest and under cover, Shane Bauer on how his detention in Iran let him to infiltrate a U.S. private prison.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

The leaders of the two largest democracies in the western hemisphere are meeting for the very first time, as President Donald Trump host the

Brazilian, Jair Bolsonaro at the White House.

National Security Advisor, John Bolton, hailed the visit as a chance to redirect relations between the two nations whose leaders do share a world

view. Both presidents talk about making their countries great again and they have been accused of divisive policies as well as spurning traditional

alliances and diplomacy.

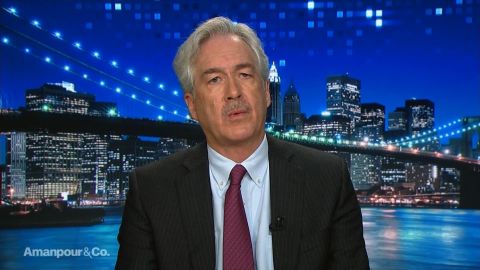

William Burns is a veteran U.S. diplomat with 33 years in the game of former Deputy Secretary of State under President Barack Obama. He held

high office under five presidents. His new book, “The Back Channel,” traces his involvement in some of the most consequential events in recent

history and passionately makes the case for diplomacy in the modern era.

William Burns joins us from New York to discuss the Bolsonaro visit and all sorts of diplomatic events around the world.

William Burns, welcome to the program.

WILLIAM BURNS, AUTHOR, “THE BACK CHANNEL: A MEMOIR OF AMERICAN DIPLOMACY”: Hi, Christiane. It’s great to be with you again.

AMANPOUR: So, your book is really interesting and you make a passionate case for a real robust diplomacy, the unsexy part of global relations but

they’re vitally necessary. I just wonder what you make of the very warm comments between Presidents Bolsonaro and Trump, and particularly about

what they said about NATO, well, President Trump did.

BURNS: Well, Christiane, I think there are very good practical reasons for the United States and Brazil to work together, whether it’s bringing

political economic pressure to bear against the Maduro regime in Venezuela or trying to expand our economic relationship. But there’s also,

obviously, the potential for a kind of populist bromance too between the two of them.

They share a kind of disdain for convention, for political institutions and they share and approach, I think, the foreign policy that’s born kind of a

muscular unilateralism and of the sense that the way you get your way in the world is to ingratiate yourself with other strong men.

And your question about the president’s comments about formal NATO membership for Brazil, I honestly don’t have the faintest clue. I

understand the logic of a major non-NATO ally relationship with Brazil. But I would assume a lot of our traditional and current NATO partners have

a view about that sort of expansion.

AMANPOUR: Let us just play what President Trump said about President Bolsonaro and Brazil in this regard.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DONALD TRUMP, U.S. PRESIDENT: As I told President Bolsonaro, I also intend to designate Brazil as a major non-NATO ally or even possibly, if start

thinking about it, maybe a NATO ally. I have to talk to a lot of people but maybe a NATO ally, which will greatly advance security and cooperation

between our countries.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

Now, I don’t know whether you were watching but obviously, he was reading the bit about the non-NATO ally and then it looked like he might have gone

a little off pieced on the formal NATO. Just put it into context, is that possible?

BURNS: Just a little off script, I think you’re right. It’s theoretically possible but it seems to me the focus of our NATO relationships right now

ought to be on the core purpose of NATO, alliances like NATO or what sets the United States apart from lonelier major powers in the world, like China

and Russia.

And what the president has done over the last couple of years, I think, has sold a lot of doubt in the minds of our traditional European partners in

NATO, as well as Canada, about our commitment to that alliance. And so, it seems to me our focus ought to be more on reassuring them as opposed to

raising kind of straight questions about new formal NATO members like Brazil.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, let’s dig down now into the substance of your book, because it is all about these allies is that you’re talking about, whether

it’s NATO alliances or other broader alliances of the United States. And you, I think, believe after a 33-year career as a diplomat, that even

before Donald Trump the idea of diplomacy was sort of decaying on the vine. What do you mean by that?

BURNS: Well, I mean, I think it’s fair to say that President Trump didn’t invent the drift in American diplomacy. After the end of the Cold War,

when the United States really was the singular dominant player in the international landscape, we became a little bit complacent, we cut the

budget for the State Department and foreign assistance over a decade or so, intake into the American Foreign Service was reduced quite a bit at the

tail end of the 1990s and then, of course, came 9/11, a deep shock to our system. And the tendency after that to invest even further in the military

and intelligence tools as opposed to diplomacy.

So, that drift has been going on for a while. I would argue however, and this is what I try to lay out in the book, that over the last couple years

in the Trump administration the White House has taken that drift and accelerated it and made it infinitely worse. And I think that’s not an

abstract problem, that comes at real cost to them — to the United States at a moment on the international landscape when diplomacy matters more than

ever.

We’re no longer the only big kid on the geopolitical bloc. Our alliances – – our capacity to build coalitions is a huge asset, and I worry that we’re squandering that.

AMANPOUR: So, I want to take that point first, the fact that, you know, we’re no longer the only kid on the block, but you are still the only

superpower on the block. I guess what I’m trying to ask you is this, and it’s quite a Trumpian view too, I think, that, OK, there was a time when

there was a superpower world, where the rules of the road were completely clear. They were two poles, two political and military poles in the world.

And then there was one, and it was called United States.

Do you believe that it is — maybe you don’t believe this, do you acknowledge that for many people it’s inevitable that the United States

sheer dominance was going to devolve really and we also have China rising as well? Was it inevitable that the United States could not maintain the

dominance that it had over so long, the American century, so to speak?

BURNS: I mean, I think it was in the natural order of things, you know, power balances were going to shift over time. The truth is I think we

accelerated that with some of the mistakes that we made, like the war in Iraq in 2003. But I also firmly believe that the United States still has a

better hand to play than any of our rivals, not only in terms of military strength and economic strength but also in terms, as I said, of our

capacity for investing in alliances and building coalitions of countries.

The challenge for us is not whether we have a better hand to play, it’s how we play it. And the window we have before us, you know, over the next few

decades in which I think we still will have a better hand to play and whether we take advantage of that moment to help reshape international

order to reflect some of those changes before it gets reshaped for us by the rise of other powers or other events.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s talk about Russia because and — because that has a NATO aspect to it as well. You write in your book that it was probably

wrong for the Clinton administration to be so muscular and to want to expand NATO so far east to encompass places like Ukraine and Georgia and

the like, it really ticked the Russians off, particularly a proud leader like Vladimir Putin. And you talk about pulling the Tigers tail, including

when you were ambassador and when you accompanied Ambassador McFaul there. Tell me what you mean, and you regret that. What do you mean about pulling

the tiger’s tail?

BURNS: Well, I think, you know, through the course of the 1990s, Russia was flat on its back economically and politically. And, you know, if you

want to understand the smoldering aggressiveness of Vladimir Putin, you also have to understand Boris Yeltsin’s Russia, a moment when, you know,

Russia was as weak as it’s been, you know, in modern history.

And, you know, therefore, that sense of grievance that animated in a way Putin and the people around him. None of that is a justification for the

aggressiveness that Putin has demonstrated in Georgia and that in Ukraine. But I think both of us operated with some illusions. And our illusion, I

think, was that we could indefinitely maneuver over or around Putin’s Russia. And it’s a Russia that, you know, through rising energy prices,

you know, managed to bounce back faster than, you know, many people imagined.

And so, the mistake, in my judgment anyway, wasn’t so much the first wave of NATO expansion in the 1990s which brought into NATO Poland and a number

of other countries. I understand the sense of historical insecurity that those countries felt as well. I think the mistake was when we continued to

kind of operate on autopilot towards the end of the George W. Bush administration and pushed hard to open the door for formal NATO membership

for Ukraine and Georgia.

And that fed Putin’s narrative that the United States was out to keep Russia down, was out to try to weaken Russia. You know, none of that, as I

said before, is a justification for actions that Putin later took but I think it was a mistake for us to push so hard in that direction in 2008.

AMANPOUR: And by the way, no coincidence then that he invaded both those two former Soviet republics, Ukraine and Georgia, and he’s dominant in

Syria now. And he did say something to you, didn’t he, when you met him, he said, “We can have good relations just not only on your terms.”

BURNS: You know, I remember vividly, that was my first meeting as the newly arrived American ambassador with Putin in 2005 and that meeting took

place in the Kremlin. As you well know, the Kremlin has built on a scale to intimidate visitors and new ambassadors. So, you go walking through

these huge halls and long corridors. And at the end of one hall you come up against a two-story set of bronze doors, you’re kept waiting there for a

minute just to let all this sink in. The doors crack open, out comes Vladimir Putin who, you know, despite his bare-chested persona, is not the

most intimidating person in terms of physical stature.

But I remember vividly he came walking toward me before I shook his hand, before I got a word out of my mouth he said, “You Americans need to listen

more. You can’t have everything your own way anymore. We can have effective relations but not just on your terms,” and that, in my

experience, was vintage Putin.

It was, you know, not subtle, it was defiantly charmless and it reflected the Putin who in a sense is kind of an apostle of payback, who’s looking to

settle scores from the 90s and get even.

AMANPOUR: Well, he has done in the in the 2016 election, hasn’t he?

BURNS: He did. He saw an opportunity to sow chaos in an American system that was already polarized and had its own dysfunctions and he succeeded

beyond his wildest imagination.

AMANPOUR: So, let me talk about more of the back channel that you talk about. I’m really interested. You mentioned Iraq and what a setback that

was for American diplomacy in the world and particularly in the Middle East, mistakes that were made in Libya and elsewhere.

So — and Syria even. Even when President Obama established his red line and then refused to cross it when weapons of mass destruction were used. I

just I’m interested in the personal, because you also write about, you know, maybe you should have been stronger, maybe you should have resigned

on principle even though many believe that you’re a steady hand, that you’re a calm diplomatic presence maybe you should have resigned. Do you

think in retrospect that you should have over the Iraq war that you opposed, over the Syria policy that you opposed?

BURNS: You know, in Iraq in 2003, it was something my colleagues and I, I ran the Middle East bureau in the State Department at the time for Colin

Powell, then the secretary of state, and we talked a good bit about that. And in the end, you know, chose to stay within the system and try to be

disciplined in our expression of our concerns.

And so, two colleagues of mine and I wrote a hurried memo at one point called “The Perfect Storm” which was an imperfect effort to try to puncture

some of the rosy assumptions that advocates the war (ph) we’re making at the time.

But to this day, my biggest professional regret is that I didn’t push harder, I certainly didn’t push effectively enough in making those counter

arguments. And, you know, my reasoning for staying inside government, you know, remains unsatisfying to me to this day.

But I do think there is a powerful argument for disciplined professionals inside government, whether it’s civilians in a State Department or in the

U.S. military. You need to have people who are going to be disciplined enough to — within the system, express their concerns honestly even when

it’s not convenient. But then, also, disciplined enough to carry out, you know, lawful instructions and orders that they get. That’s the only way in

which you can make a system work.

AMANPOUR: So, just quickly, do you admire Secretary of Defense James Mattis’ decision to resign over policy that he felt unable to uphold on

Syria?

BURNS: I do, I do. I have known Jim matters for more than 20 years. I have great admiration for him. That was not an easy choice for him to make

but I have great respect for him.

AMANPOUR: And that, of course, was about the president’s precipitous decision to withdraw all U.S. troops from Syria before General Mattis

sought the job had been done.

Now, you did stay in office and you actually went on to conduct the kind of back channel negotiations that you described in your book and it’s the

title of your book, “Back Channel,” and that was with Iran. And obviously, it’s been a very controversial thing, the president — now President Trump

has pulled the U.S. out of the nuclear deal.

Just tell me how difficult it was to start this process, not the public stuff that we all saw but to just start a process to try to defang the

scariest thing about Iran and that was a potential nuclear program — nuclear military program.

BURNS: Yes. I mean, as you say, Christiane, it was a huge challenge. You have to remember that we had gone for 35 years without sustained diplomatic

contact with one another, relations were a minefield and nobody really had a good map.

And I’ve been — I was convinced for some time that we had to test the possibility of direct diplomacy over the nuclear issue because the risks of

an unconstrained Iranian nuclear program, let alone a nuclear armed Iran, were enormous. And so, I think it’s a huge credit to President Obama and

First Secretary Clinton and then Secretary Kerry, that he was willing to take the risk of testing this. And I still think that it was important to

get it started quietly given the baggage on both sides politically at the time.

It surprises me to this day that we managed for the better part of 2013 to keep it quiet in this day and age. The Omanis prove to be very effective

facilitators and Oman was a place where you could have, you know, a long three-day set of negotiations with the Iranians and do it relatively

quietly. And we had nine or 10 rounds of negotiations during that period of secret talks.

And of course, that then, I think, created the basis for working with our international partners which was crucial to producing first an interim

agreement late in 2013 and ultimately, the Comprehensive Nuclear Agreement a couple years later.

AMANPOUR: We really don’t know what’s going to happen now that the president has pulled the U.S. out and has imposed sanctions and we don’t

know what’s going to happen, but we’ll wait to see that.

But given the fact that you did conduct such deliberate and extensive back channel negotiations and then the whole public negotiation, let’s just

switch to the other enduring issue in the Middle East, and that is between Israel and the Palestinians.

I mean, they have almost been there’s been nothing for the last several years. I mean, just a big fat nothing. I mean, the Palestinians have

practically called off any conversations with the United States, the U.S. has put its cards on the table, moving its embassy to Jerusalem, and we

keep hearing about the Kushner or Trump peace plan and nothing. What do you think having really worked on that issue as well? Is there any chance

of peace between those two sides?

BURNS: I think there’s still a chance but I think the chances of a genuine two-state solution are becoming increasingly remote. You know, I’ve seen

moments of significant progress when I worked for Secretary of State Baker in the run up to the Madrid Peace Conference in 1991, which is where I

start the book. That, it seems to me, remains to this day an example of hardnosed persistent diplomacy.

What I feared today, and we’ll see, you know, when the White House’s plan is eventually released, but what I fear is that it’s based on a whole set

of flawed assumptions made first that you can essentially negotiate such an approach with just one party to a conflict since it’s been almost a year, I

think, without any, you know, real diplomacy between Palestinians and Washington.

Second, that you can somehow negotiate over the heads of the Palestinians and use the shared concern, legitimate shared concern, that a number of

Arab States and Israel have about the threat posed by Iran.

Third, that somehow you can substitute economic incentives for Palestinians for their legitimate aspirations to political dignity. I don’t think

that’s worked in the past, I don’t think it’s going to work now.

And last and not least, I think, another flawed assumption that somehow time is on our side and that approaching a two-state solution is not an

urgent issue. I think it is urgent simply because if you look at the best interests of Israel as a Jewish democratic state, that’s going to be harder

and harder to sustain when the reality a few years from now is in the land that Israel controls, from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean, Arabs are

in a majority.

So, I think for all those reasons, there ought to be a greater sense of urgency. And I worry about the flaws that appear to be in the assumptions

underlying the White House’s approach.

AMANPOUR: And I guess briefly but most importantly after writing this and digesting your 33 years, do you see solutions for America to come back to

its traditional role of effective and pragmatic diplomacy around the world?

BURNS: I do. I’m an optimist. I think most diplomats are. I’m well aware of the corrosive damage we’re doing to ourselves today. I think we

can recover from a lot of that but some of it may be more enduring. But I really do believe that it’s possible to renew diplomacy as our tool of 1st

resort. We need it cold bloodedly more than ever on the current landscape, and that’s going to require some hardnosed reforms in the State Department

as well.

You know, while lots of individual diplomats can be very innovative, very entrepreneurial, the State Department is an institution is rarely accused

of being too agile or too full of initiative. But we’ve got to repair that but we’ve also, I think, got to, you know, fix the domestic disconnect in

American society.

You know, I think most Americans, in my experience, don’t need to be convinced of the importance of disciplined American engagement in the

world, but they’re not so convinced a part about is the discipline part because they have seen administrations overreach. And so, that’s going to

be another challenge. But I think it is possible to renew diplomacy and I think in doing that, possible I think to recover from a lot of the damage

that we’re doing to ourselves today.

AMANPOUR: Well, that is good to hear. William Burns, Author of “Back Channel,” and president of the Carnegie Endowment for Peace, thank you so

much indeed for being with us.

BURNS: Thank you very much, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: Thank you.

And, of course, we discussed at the beginning of our program, America First and Brazil First. They are, of course, well-known slogans. And we’re

going to look now at another first, the first woman on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Now, it’s true that the second woman, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, has surpassed iconic superstar status, with like “RBG,” in Hollywood

dramatizations of her incredible life and career. All the attention perhaps even overshadows the first female justice, that was Sandra Day

O’Connor who was sworn in in 1981 after being nominated by President Ronald Reagan.

While her voice was often the loudest on the court, over time it’s faded along with the story of her rise. A journey Justice O’Connor was all too

aware mirrored the long road American women have had to walk.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

O’CONNOR: It wasn’t too many years before I was born that women in this country got the right to vote in the 1920s, for heaven’s sakes, that isn’t

that long ago. And things moved very slowly for women in terms of having an equal opportunity in the workplace and so on.

And in my lifetime, I have seen unbelievable changes in the opportunities for women. It’s been so interesting to see.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: That was in 2003. Now, author, Evan Thomas, dug into the highs and the lows of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s life in his biography which

is simply titled “First,” where he got extraordinary access to everything, from her papers to her late husband’s diary. And Evan Thomas joins me now

from New York.

Welcome to the program.

EVAN THOMAS, AUTHOR, “FIRST: SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR”: Hi, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: Hi, Evan. It is really amazing actually to see this book and to focus now on her, because for all sorts of fantastic reasons, it is Justice

Ruth Bader Ginsburg who’s getting lionized all over the place for her amazing, amazing groundbreaking legal decisions for women.

But how do you think — I mean, maybe it’s unfair — Sandra Day O’Connor stacks up against Justice Ginsburg?

THOMAS: They’re different. Justice Ginsburg was an activist, a feminine icon and an activist and she deserves a lot of attention. But Justice

O’Connor who came 12 years before Justice Ginsburg was something different. She cared about power, about getting things done. Justice Ginsburg was

often in dissent, she rarely controls the court.

Justice O’Connor and her 25 years was the fifth vote, the decisive vote of 330 times. It was Justice O’Connor who kept alive affirmative action for

25 years. It was Justice O’Connor who kept alive abortion rights for 25 years.

She was a huge force on freedom of religion. She was the fifth vote in Bush v Gore. She had enormous power, maybe more power than any American

woman has ever had.

AMANPOUR: Well, you just mentioned Bush v Gore. Of course, controversial, because many people who study the Supreme Court believe that it was that

decision that turned an impartial court the highest in the land, the highest in the world, into another political instrument.

THOMAS: Right.

AMANPOUR: Did Justice Sandra Day O’Connor ever talk about that? Did she have any doubt about her vote and about what that decision by the Supreme

Court meant for politics since 2000?

THOMAS: Justice O’Connor had very few regrets in life, was not that kind of person. But on Bush v Gore, she did express some regrets privately and

also once publicly to a Chicago — to “The Chicago Tribune” saying that, “Well, maybe the court should not have taken the case. Maybe we should

have let it go, said goodbye, and let it go.”

This is a very tough case. O’Connor is a pragmatist and her belief was that if the Supreme Court had allowed the recount to go on, you remember

the issue was all these ballots and can you count them or not. And so do you stop the recount and let the Republican win or do you let the recount

go on?

Her belief was that if the recount went on and on, and we’re going on and on, eventually it would have been back in Congress because there was a

possibility that you have Republican slate certified by the Republican secretary of state, Gore winning yet another slate.

Under the rules, if it’s tied like that, you know who breaks the tie. The tie is broken by the governor of the state of Florida whose name was Bush.

And so O’Connor looked down the road and saw a huge car wreck and said, “Look, we’ve got to deal with this now.”

AMANPOUR: It is really amazing to go back and think of that. You talked about her political philosophy, that she was a pragmatist and often she

made the deciding vote.

I just want to ask you also about what we started talking about, about her feminism, her understanding of her role as a woman. And we have seen some

of the writings in your book where she penned an instruction for her own funeral.

And she said in 1987, “I hope I helped pave the pathway for other women who’ve chosen to follow a career. Our purpose in life is to help others

along the way. May you each try to do the same.” That was what she was trying to say to other women.

THOMAS: Yes. I mean she saw herself as a bridge. She was in many ways a traditional woman, a Country Club Republican. She played golf.

She looked — in her later years, she looked sort of matronly early. She was a great beauty when she was a Stanford student especially. But she was

a fairly conventional woman in that sense.

She was not a feminine activist. She understood that you needed the transitional figure had to be in a way unthreatening to men. That was just

the reality.

And she was very good at men. She was flirtatious in a non-sexual way. She was flirtatious with men. She got along with men. She could be very

very tough.

And well, I’ll tell you one story. She’s in the Arizona legislature. You can imagine what that was like in 1970, pretty much all male. They drank a

lot. There was a lot of sexual harassment.

One of her nemesis was a guy who was a drunk and she called him on being a drunk. And he said to her, “If you were a man, I’d punch you in the nose.”

She said, “If you were a man, you could.”

So she knew how to stand up but she was careful about it. And she picked her shots.

AMANPOUR: Well, look, just illustrate her sort of soft, if you like, you quote her after law school and this is what the partner who’s interviewing

her says to her, “Day, this firm has never hired a woman lawyer. I don’t see that it will. Our clients won’t stand for it.”

She says, as she likes to tell the story, the Gibson Dunn partner asked, “Well, how well do you type?” She answered, “So-so”. She said, “Well if

you type well enough, we might be able to get you a job as a legal secretary.”

I am sure there are many many women even sitting on the Supreme Court right now who recognize that and in many many other professions.

Anyway, she had the last laugh. But let us just talk about men because one of the really interesting stories that I had no idea about was her

relationship and flirtatious relationship and romantic relationship with one William Rehnquist who went on to be the Supreme Court Chief Justice,

wanted to marry her. What was all that about?

THOMAS: A complete secret. They never told anybody. But my wife Osce and I were going through her letters and we were looking for love letters

between Sandra and John, her husband.

What we found were love letters between Bill Rehnquist and Sandra in law school, 1952. And they had dated a little bit. Bill Rehnquist fell in

love.

And going through these letters, there’s a one that says, “Sandy, will you marry me?” Well, she didn’t. The answer was no. She married John.

Ultimately, Bill Rehnquist married the woman he loved and Sandra married the man that she loved.

But this is a little awkward when Sandra gets to the Supreme Court. And you can understand why they never told anybody. They let it be known that

they had dated.

And when Sandra Day O’Connor first came on the Supreme Court, Harry Blackmun who sat next to Rehnquist — Justice Blackmun sat next to

Rehnquist, leaned over to Rehnquist and said, “OK, no fooling around.”

So they’re already teasing Rehnquist about it without even knowing that he — well —

AMANPOUR: OK. But I love the story. And you can just tell it to us as briefly as possible how Rehnquist actually failed to marry her because he

failed a P-parental test.

THOMAS: He had bad table manners. He offended Mrs. Day because he had bad table manners. Also, the really rigorous tough father, Mr. Day, gave

Rehnquist a fried cow’s testicle to eat as a form of harassment. This is life on the ranch. And he ate it gamely but I think that Rehnquist

basically flunked the parent test.

AMANPOUR: Now, let me ask you something that’s serious and sadder. Sandra Day O’Connor chose to step down. Her husband was developing dementia,

Alzheimer’s, and she thought that she needs to step down to take care of him.

And afterwards, she regretted it. Partly also because he didn’t recognize that within six months of her stepping down, and he even took up with

another lady in the care home he was in. Fill in those blanks. It’s really interesting.

THOMAS: Yes. Well, John O’Connor got Alzheimer’s in about 1996 and Sandra took care of him for as long as she possibly could. She took him to our

chambers.

But at some point she decided he had sacrificed for me when we moved to Washington, he’d been the big man in Phoenix, he sacrificed for me. Now,

I’m going to sacrifice for him.

And so she resigns from the Supreme Court before she was ready. But within six months, he couldn’t recognize her. And as you said, he formed what

they call a mistaken attachment. This is not uncommon for Alzheimer’s patients but he had a girlfriend and he’d be holding the hand of the other

woman. And Sandra Day O’Connor would come in and Sandra would sit down and take John’s other hand.

AMANPOUR: It’s amazing.

THOMAS: He — publicly, she was happy for him because he had been depressed. But privately, of course, her heart was broken.

AMANPOUR: I can imagine. And what does she think legally what happened to her legacy, what happened to the Supreme Court when she “prematurely

stepped down”?

THOMAS: Well, the more hardline conservatives came and she was replaced by Justice Alito who’s more doctrinaire. Justice O’Connor was conservative in

many ways but pretty middle of the road, a compromiser. I mentioned on Affirmative Action Abortion, she found compromises.

Alito is much more hardline. So, on both affirmative action and abortion, they are now threatened, if that’s the right word. They could be changed.

And she feared that her pragmatic middle of the road approach would be discarded for a more doctrinaire conservative approach.

AMANPOUR: And as for her, herself, Sandra Day O’Connor, how is she? How did you find her? How was she when she was involved with you writing this

book?

THOMAS: Yes. Well, when I first find them here, she worked around with 150 people and called — Justice Souter was down there. This is Phoenix.

And she said, “Hi, toots” to Justice Souter. So she was an amazing kind of ability to cope but she knew that she had dementia. And it creeps up on

you slowly now. She’s — and not in a good way.

As you know, she was able to talk about her marriage and her life. I didn’t get heavily into the cases with her. Now, it’s a progressive

disease. Now, she’s — sadly, she’s got dementia.

AMANPOUR: It’s a remarkable story and it’s a remarkable arc of her life. Really incredible story first by Evan Thomas. Thank you very much indeed

for joining us, Evan.

THOMAS: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: Let’s turn now to another less palatable aspects of the American legal system as we delve into the harsh reality of its prison system.

After being released from Iran’s notorious Evin jail, going undercover as a prison guard in Louisiana might seem a strange choice, but not for

Investigative Reporter Shane Bauer. In his new book, American Prison, Bauer details the brutality of life behind bars.

Despite being tortured by the Iranian regime and spending months in solitary confinement, Bauer was left conflicted by his experiences as he

told our Michel Martin.

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Shane Bauer, welcome. Thank you so much for talking with us.

SHANE BAUER, AUTHOR, AMERICAN PRISON: Thanks for having me in.

MARTIN: You’re actually known for your international reporting. And I think people will remember, many people who follow these things will

remember that you were actually arrested after a hiking trip in Iran. You spent two years in one of the most notorious prisons in Iran.

So what made you want to investigate American prisons after an experience like that?

BAUER: I didn’t really intend to when I got out. I thought I would go back to the Middle East where I was working as a reporter. But I came

home, was kind of readjusting.

When I was ready to kind of get back to my work, I started investigating our use of long-term solitary confinement. Having been in solitary myself

in Iran, having been on hunger strike, it was something that I was kind of naturally drawn towards.

And I learned that we had have about 80,000 people in solitary confinement in this country given — a given day and thousands of people who’ve been in

for more than 10 years. So after kind of doing that reporting, I just — I kept getting pulled kind of deeper and deeper into our prison system.

We have the largest prison system in the world, about five percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. And in that

reporting was kind of constantly coming up against walls. It’s very difficult to get access to prisons in America.

And as a journalist, if you get in, you typically — you look at a kind of a scripted tour, guided tour. You usually can’t even request specific

inmates to interview so they will provide you with somebody. So it’s a frustrating process.

MARTIN: So what happened? You just pick your head up one day and said, I’ll just get a job as a prison guard?

BAUER: I just filled out an application on the corporate website. I didn’t lie in my application. I put my current job which was for “Mother

Jones Magazine”. And within a couple of weeks, I was getting calls and requests for job interviews.

I had decided along with my editors that the ground rule would be that I would never lie in doing this project. So before I did these interviews, I

just couldn’t imagine it working. If they say like why do you want to —

MARTIN: Why do you want to work in a prison? So —

BAUER: — work in prison or something but they didn’t.

MARTIN: They never asked you why?

BAUER: No. And they didn’t ask me my job history. They just asked me some kind of boilerplate questions about how I work with others, what I do

if a boss tells me to do something I don’t want to do. They were desperate for employees. The job that I eventually took in Louisiana paid $9.00 an

hour.

MARTIN: What made you take that job?

BAUER: Ultimately, I chose Louisiana partially because it had the highest rate of incarceration, not only in the country but in the entire world.

Winn Correctional, the prison I worked at, was the oldest medium-security private prison in the country. So that seemed interesting to me but it was

a fairly random decision.

MARTIN: So just tell me about like what was your first day?

BAUER: I’m really nervous. I’m kind of imagining all these scenarios. I’m worried that they’ve already found out that I’m a reporter.

And I go in for training and I meet the other cadets. Some of them were just at high school, 18-years-old, 19-years-old. There was a single mom

who was there because she wanted health insurance for her kids. It was a kind of a hardscrabble group and —

MARTIN: Were they all white?

BAUER: No, they weren’t. It was a mix of white and black guards. And actually, the majority of guards were black and the majority were women

also.

MARTIN: The majority were women?

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: Interesting.

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: One of the things about your book that struck me is that for a lot of people reading it, it’s absolutely shocking.

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: But for a lot of people, it isn’t.

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: And I just wonder when it sort of occurred to you or whether it struck you that you were really in a different world.

BAUER: Immediately. Yes. I mean my second day of training, I remember the instructor asked the class, “What would you do if we saw two inmates

fighting?” And one cadet said we’d break it up, someone said to call back up.

And he said, do not get in the middle of a fight. He said your job is to shout at them stop fighting. And he said we’re not going to pay you enough

to get in the middle of it. And if those fools want to cut each other up, then happy cutting.

MARTIN: How did you understand that instruction?

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: It’s just that simple which is we’re not paying you and if you get hurt —

BAUER: Yes. I mean I think

MARTIN: — too bad?

BAUER: — the instructors had actually said to us that part of our job is to deliver value to our shareholders. If we get hurt, cost company money

and —

MARTIN: They said that to you?

BAUER: They said that we — our job is to deliver value to our shareholders, yes. We had to do things that like telling people stop

fighting. Kind of like in court, it shows that we’re doing our job, we’re instructing them to stop.

MARTIN: You’ve made a point several times of highlighting the fact that this is the private prison system, right? Could you just talk about why

that distinction is so important?

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: What point you’re trying to make with that.

BAUER: The private prisons represent about eight percent of our country’s prisoners. They are run by corporations, corporations that are traded on

New York Stock Exchange. These companies run prisons generally for states because they save money.

So they run their prisons cheaper than the states do. They’re trying to turn a profit so they’re cutting corners wherever they can. And I saw a

lot of this.

One of the main ways they save money actually is through staffing. That’s the main cost of running a prison so they pay staff less, they hire less

staff. At the prison I was in, there were about 1,500 inmates and about 25 guards on duty on a given day.

They also were clearly cutting corners on medical care. I met a man who had lost his legs and fingers to gangrene who had been going for months at

the infirmary asking, telling them that his legs hurt, they need help, and they would give him a couple of Motrin and send him back.

MARTIN: Wait, wait. He lost his fingers and his legs while he was in prison?

BAUER: Yes. So —

MARTIN: Because they did not treat him?

BAUER: Yes, the issue comes down to the fact that the company by their contract, if they send a prisoner to hospital, they have to pay. So

there’s a lot of reluctance to do that when they’re making — the state’s paying them $34.00 a day for each inmate where a hospital trip will cost

thousands.

MARTIN: Wait, wait. They’re paid — wait. The state pays $34.00 a day per prisoner.

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: So that has to cover food and personnel and medical care —

BAUER: And profit.

MARTIN: — sheets laundry.

BAUER: On top of that, yes.

MARTIN: Do you think that the prisoners understood that they were there for the prison to make a profit?

BAUER: Oh, absolutely.

MARTIN: Really?

BAUER: They’re talking about it all the time. The prisoners would say to guards like you’re not making enough money, this company is exploiting you,

they’re just trying to make a profit. And I would see guards and prisoners kind of bonding over their shared disdain for the company.

MARTIN: The thing about your book that you describe is that just how kind of demeaning it is —

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: — but for both parties.

BAUER: Yes. Being a guard, I really saw how much they are kind of caught up in the system and exploited in a lot of ways. I mean they’re generally

poor people from a poor town.

They feel they have no other options so they take a $9.00 an hour job. They work 12 hours a day.

MARTIN: Everybody works 12 hours a day, that’s not —

BAUER: Minimum.

MARTIN: — an emergency?

BAUER: Minimum.

MARTIN: Twelve hours a day minimum?

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: Can I read a passage from the book here? You said that research shows that on average, about one-third of prison guards suffer from post-

traumatic stress disorder, more than soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. And you write according to one study, corrections officers on

average commit suicide at two-and-a-half times more than the population at large. And you said that they also have shorter life spans. Why? Why is

it —

BAUER: Yes. I mean it’s just an incredibly stressful job. And there are so few people working so you literally can’t do all the things that you’re

meant to do.

We’re supposed to check prisoners as they enter the unit. For example, make sure that nobody has weapons. And when you’re two guards and you have

350 prisoners and you have to unlock the doors, put them inside, it’s absolutely impossible. You literally cannot do that.

MARTIN: You obviously have personal courage and you obviously have fortitude but I do find myself wondering like how you survived it.

BAUER: Yes, yes. I changed a lot inside the prison. And when I first went in, I thought I’ll just be like an easygoing guard, kind of just hang

back and it will be fine but it’s not — it’s never like that.

You have to — in prison, anyone in prison, whether you’re a prisoner or a guard, you learn very quickly that you have to kind of set lines, you have

to hold those lines, and you can’t ever let people kind of push your boundaries.

MARTIN: You said at one point, you became much more authoritarian than you ever expected you would be. Can you just give an example of

that?

BAUER: When prisoners come back from chow, for example, when they’re eating, we have to put them back in the dorms. There’s always some that

kind of running around and just kind of they’re hard to chase them to the dorms.

There was one guy that was like that and I kind of had trouble with. And I just start ordering him, go to your tier, and he’s kind of yelling at me.

And then we’re kind of like have a little tension and I put him in, I slam the door.

And I turn around and leave and I hear him saying something like you’re going to end up dead and so I kind of paused and thought for a second like

what am I supposed to do when something like this happens. I called into my radio for a supervisor. Somebody came down and I just told him like I

want this guy sent to the segregation unit, essentially solitary confinement.

MARTIN: You sent somebody to solitary?

BAUER: Yes. And —

MARTIN: Wait, wait, wait. The guy who was in that —

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: — solitary for two years, you sent somebody?

BAUER: Yes, exactly. So when I’m in that moment, I’m kind of thinking of like how do I deal with these people who are kind of challenging my

authority basically. And that is really the only means we had, it was to send them away.

And there is this kind of voice in my head that was like afterwards it was like I didn’t see him say that, was I sure that this is the person that

said those words and — but the other voice was like I need to set an example and it doesn’t really matter. I need to show all these people who

see this happening that I’m willing to do that.

MARTIN: One of the really hard things about the book is your description of the fact that so many people have a serious mental illness —

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: — that wasn’t being treated.

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: And that they knew they needed help and they didn’t get it.

BAUER: My first day on the job, I was stationed on suicide watch. It’s common for new guards to be put there. It is kind of the worst job in the

prison.

You essentially sit in front of a cell where an inmate is in solitary confinement and you watch him for 12 hours. Every 15 minutes, you make a

note what he’s doing. Usually, the prisoner does not want you sitting in front of a cell so there’s kind of this just ongoing dynamic that is tense

and it’s just not nice.

And so I’m sitting in front of this cell, cell of an inmate named Damien Costly. He’s on suicide watch which means that he is not allowed to have

clothes.

MARTIN: He has no clothes?

BAUER: Right. He has one blanket, a tear-proof blanket. It’s all that’s allowed in a cell. No reading material. His food is worse than the rest

of the prison. It’s — the caloric value of the food that he gets is below USDA standards.

And they actually told us in training that part of the reason that they keep the conditions that way is to discourage people from going on suicide

watch, from saying that they’re suicidal so they get sent there because it cost a lot more money because the guard to prisoner ratio is one to one

there, rather than one to 175.

So Damien told me like, “Get away from the front of my cell.” He threatened to jump off his top bunk and break his neck so — which I’m

required to report so I reported it. Six hours later, a psychiatrist comes and talks to him.

There is, by the way, for the whole prison of 1,500 inmates, one part-time psychiatrist. And a third of the inmate population has mental health

issues.

Months later after I leave the prison, I am contacted by a lawyer who represented Damien’s mom, she had found out that I was a reporter who was

working at the prison. And she said that he’d committed suicide.

I learned later — I went and visited her and she gave me access to a lot of his documents that he had been on suicide many — suicide watch many

times. He had been in hunger strike many times to demand mental health care.

He had been on a wait list for two years for a mental health group. And it was clear that he was wracked with guilt for his crime. He had killed a

man. Other prisoners said that he would talk to him about it and say that he was suicidal.

And he eventually hanged himself. And when he died, he weighed 71 pounds.

MARTIN: The name of the institution you were in was Winn?

BAUER: Yes, Winn Correctional Center.

MARTIN: Have they reacted as an institution? How did they respond to the book?

BAUER: It comes out in the local media that I was a reporter working there. And the company then contacted Mother Jones and they threatened to

sue if we published a story.

Ultimately, our lawyers said they had no legal standing. I didn’t lie. I did my job they actually offered me a promotion while I was there.

MARTIN: They offered you a promotion while you were there?

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: There are those who will hear our conversation and say why do I care, it’s too bad. But if you break the law, this is the consequence, why

should I care. What do you say to that?

BAUER: I mean if your kid gets to a fight at school, do you want to lock him in a closet for two weeks just because he broke the rules? I mean I

think we need to ask ourselves what kind of society we live in.

And even if you don’t care about these people, these people — most of these people get out, they’re back in our communities. And being

essentially warehoused for years or decades is not rehabilitating anybody.

MARTIN: Every society has people that, for whatever reason, they feel a need to punish through separating from everyone else, but what you

describe, it’s barbaric.

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: OK. But the question is why? Why do you think it’s like that?

BAUER: I think there’s a lot of ways to answer that question. I mean, in this prison, in particular, there’s a profit motive that plays a lot into

it.

MARTIN: Do you think that a public prison is better?

BAUER: There are certain issues that occur in private prisons that are worse than public prisons, like the lack of security and even worse medical

care. But the public prisons in this country are also abysmal.

I mean it’s not in any way — I would never say that state of current public prison is the goal of humane prison, it’s not. A lot of the same

issues occur there. The suicide watch, for example, all prisons have this.

MARTIN: The extended use of solitary confinement is something —

BAUER: Exactly.

MARTIN: — that has gotten quite a lot of attention.

BAUER: Yes. And most of the long-term solitary confinement is in public prisons, not in private prisons.

MARTIN: Do you have a theory of everything, of like why imprisonment in this country is the way it is?

BAUER: Well, I think part of it is the fact that we have so many people in prison. It’s just an astronomical amount of people. There are 2.3 million

people behind bars and that costs so much money.

There’s no way to hold that many people in a way that is humane that is not going to just bankrupt the states. That is kind of the core of the

problem. And then we have set back from there and ask why we have so many people in prison and —

MARTIN: I am going to ask that question. Do you have a theory of that?

BAUER: I mean I think there are many factors. We live in a racist society that’s been proven in many ways that policing targets — police target

people of color. The justice system imprisons people of color longer than white people.

There are also issues that are — the length of sentencing has increased a lot over time. We put people away for longer and longer. Mandatory

minimum sentencing is a huge issue. We’re locking people up for so long and they’re not getting out.

MARTIN: You have an interesting analysis in the book where you actually make the connection to slavery.

BAUER: Yes.

MARTIN: So what do you mean?

BAUER: Our prison system in the south especially grew out of slavery in a lot of ways. I mean when slavery ended, the southern prison systems were

all privatized and prisoners were leased to businessmen and planters to work on cotton plantations, to work in coal mines, to build railroad

tracks.

And they were like — enslaved people had been, driven by torture to meet quotas, they’re whipped. And the death rate actually after slavery of

convicts in the south was much higher than it was for slaves. Throughout the south, it was between 16 and 25 percent of convicts who die every year.

And this went on for decades. And even when that system ended, the states, when they stopped leasing prisoners to these companies, they bought

plantations themselves and worked prisoners on plantations, continued to whip prisoners.

Arkansas until 1967 was allowing whipping. And what I learned in my research was actually the founder of the Corrections Corporation of America

started his career running a cotton plantation prison in Texas. This was the size of Manhattan, where prisoners were working in cotton fields,

having to meet quotas. He’s living in a plantation house. He’s served by prisoners which they called house boys.

So he’s living a life that is very reminiscent of the life that slave owners were living 100 years earlier. This man in particular was — he was

— these prisons at the time in the ’60s and ’70s were public prisons, they weren’t private. But he was running them at a profit, putting money into

state coffers. He was really the last person to do that.

And when he stopped working in these prison plantations, it happened to coincide with a huge boom in the American prison population, which really

changed the system a lot, made it so that states were scrambling to build prisons fast enough. And a couple of businessmen approached him.

END