Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Emilio Estevez is back in the library. Only this time, the Breakfast Club heartthrob will not be dancing. Estevez is the writer, director, and star of a new film called “The Public.” It’s the story of social activism and civil disobedience set in Cincinnati, Ohio, centering on an uprising that was staged by the city’s homeless inside the public library. And our Alicia Menendez has been speaking to Emilio Estevez about this.

ALICIA MENENDEZ: So I loved this film, “The Public.” And it has a very interesting premise and arctic cold blows into Cincinnati, the homeless population decides to occupy the public library. And what starts as an act of civil disobedience ends up becoming a very tense standoff with the police. I imagine this was not an idea that was easy to sell.

EMILIO ESTEVEZ, DIRECTOR, WRITER AND ACTOR, “THE PUBLIC”: No, certainly not. This was an idea that actually started 12 years ago this week, as a matter of fact. It was April 1, 2007, an article appeared in the “Los Angeles Times”. It was written by a retiring Salt Lake City librarian named Chip Ward. And the essay was about how libraries had become de facto homeless shelters and how librarians are now tasked with being first responders and de facto social workers. And so, it was — for me, it was an eye-opening piece and I was very moved by it. And so I began to imagine what it would look like if the patrons decided to stage an old-fashioned ’60s sit-in, how law enforcement would react, how the media might spin it, and how a local politician in the middle of a campaign cycle could use it for his political gain.

To your point, I would go into offices and I’ll say, don’t you understand, don’t you see, this is exactly what’s happening. And I think people just — they didn’t see the humor in it. They didn’t see the humanity in it. They couldn’t imagine a movie taking place in a library, Breakfast Club being successful. And so for me, it was very frustrating and yet ultimately, isn’t it really all about timing. And I think the movie is way more relevant now than it would have been had we made it even five years ago. I mean we just experienced this extraordinary polar vortex, just descended on the middle of the country, and we were watching people dying in the streets.

MENENDEZ: One of my favorite moments in the film happens pretty early on. It’s a quiet moment but I want to take a look at it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ESTEVEZ: It’s going to be brutal the next couple of nights for sure.

MICHAEL K. WILLIAMS, ACTOR, “THE PUBLIC”: We could all come stay at your place.

ESTEVEZ: I would if I could.

WILLIAMS: You could but you won’t. No judgment here, though.

ESTEVEZ: Look, Jackson, use it to get some food, maybe a room.

WILLIAMS: You’re going to offer me money and then tell me what to do with it?

ESTEVEZ: Well, no. I was just suggesting a few things that I thought you might need. That’s all.

WILLIAMS: How do you know what I need? I’m messing with you, man. With a cause.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: Michael K. Williams, the best of the best in terms of being able to hold a tense moment, pivot from drama to comedy.

ESTEVEZ: He’s so good. He’s so solid in this film. The whole cast is.

MENENDEZ: I mean incredible cast.

ESTEVEZ: He’s electric in this film.

MENENDEZ: But what I love about that exchange is it illustrates what we get wrong about homelessness.

ESTEVEZ: Well, it’s conditional giving we see in that scene, really. We need to, I think, divorce ourselves from that outcome because that’s really none of our business. If we’re — if we give, we give freely and we give without condition. And it’s really none of our business where that individual who’s asked for that money is going to spend it.

MENENDEZ: When the protagonist of the film is the character you play, Stuart, a white librarian, how do you avoid the trope of the white savior?

ESTEVEZ: Well, that’s a good question. We made sure that I’m surrounded by a very diverse cast. It’s a very inclusive cast. And my character doesn’t initiate. My character follows. This is initiated — the lockdown is initiated by Michael K. Williams who in turn doesn’t want to speak to the police. And so he inevitably uses Stuart as the mouthpiece for the group but Stuart does not want to be in that position.

MENENDEZ: But why choose this as the project to spend 12 years on?

ESTEVEZ: This is one of those projects that it was — it’s been sort of said that, well, this is a labor of love. It was really more a labor of purpose. I, you know, was informed by a great deal by my father’s activism. He’s been arrested 68 times, all nonviolent civil disobedience actions for anti-nuclear movements, for homelessness, mental health issues, and immigration. And so he’s been out there protesting in the streets. And the movie is, you know, I would say it’s informed by those — every one of those 68 arrests. And what I mean by that is I would watch him get arrested. It was oftentimes on national television. And my — I would sit and watch him get carted off in handcuffs, reciting the Lord’s Prayer and he looked like a lunatic. And for me, as a young man, it was — I understood it fundamentally but I didn’t understand it spiritually until I started working on this picture.

MENENDEZ: And this film deals not only with the social activism component of this but also the politics of this issue. Let’s take a look at another clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ALEC BALDWIN, ACTOR, “THE PUBLIC”: Why did you lie to me?

ESTEVEZ: Librarian’s duty is to protect the privacy of the patrons. Maybe you heard of the Connecticut Four.

BALDWIN: Yes, I’ve heard of the Connecticut Four. I read that appellate case when I went back to graduate school 10 years ago. Goodson, your intellectual vanity is breathtaking. These people that you’re protecting, your patrons, is it worth it? Is it worth throwing your life away for? Would they do the same for you? Not on your life, pal. I’ve been working with drunks and addicts and the mentally ill for my entire career, all day, every day, and they’re not your friends. They don’t give two [bleep] about you. All they care about is their next hit, their next bottle, their next meal, and they will beg, borrow, and steal to get that from you. But you already know that, don’t you?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: So good. We have not seen that Alec Baldwin in a while.

ESTEVEZ: No. I’m so proud of his performance in this film. Again, he’s been known in the last, at least, the last 15, 20 years as being a comedic actor with 30 Rock and the “SNL” sketches that he’s been doing. And when he said yes to this, I was thrilled because I thought, let’s get – – let’s see Alec again in a very dramatic role. Let’s remind people that this is how we all grew up watching him. And he just sinks his teeth into this and he does an extraordinary job.

MENENDEZ: The situation ends up being a standoff with the police. What do you want viewers to take away about the relationship between the homeless population and the police officers that try to keep them safe?

ESTEVEZ: Sure, that, you know, I think we see over and over again the criminalization of the poor and the marginalized and it’s oftentimes at the hands of law enforcement. I think that my hope the takeaway is that audiences begin to park their bias at the door when they confront or encounter somebody on the street, an individual experiencing homelessness who may be suffering from mental illness. We don’t know how that person arrived at this unfortunate place in their life. But oftentimes, we assign a story to how they got there and oftentimes that story is wrong. I’m sure you’ve had people assign a bias or bring their bias and assign a story about how they think you arrived at a certain place. That happens to me every day. And so let’s stop doing that to individuals experiencing homelessness. Let’s stop treating it like a condition because it’s not. It’s not a condition. It’s a situation. And it’s a situation that we can, I think, assist in getting people out of.

MENENDEZ: It’s not just the relationship between the homeless and the police, though. It’s also the way that we in the media sometimes frame these issues.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right.

MENENDEZ: What did you want the takeaway to be there?

ESTEVEZ: So, oftentimes, you know, actually on the daily, almost every channel, we see that breaking news, so much so that we’re numb to it. And I think the media oftentimes goes to, if it bleeds, it leads, and they lean into the negative. And that’s what happens in the case of this particular reporter, Gabrielle Union. She’s not really interested in the story and if she were to peel the layers back and to — there’s actually a bigger story there if she were to pay attention to what was really going on inside. And so therein lies the confusion. And, of course, in steps the politician who wants to spin it for his own political gain because he’s in the middle of an election cycle. And you have this unholy marriage between politics and the media, which can never exist in real life, of course, but in this film, there it is. And it exacerbates the situation.

MENENDEZ: You grew up in one of the most influential families in Hollywood and now you live in Cincinnati, which would be really easy to read as a rejection of Hollywood and a rejection of the way you were raised.

ESTEVEZ: Sure. Well, my mom was born in Cincinnati, raised across the river in Kentucky. My dad was born in Dayton. So they were born 45 minutes apart. Essentially, they met here in New York in 1960 and have been together ever since. And what I love about Cincinnati is it reminds me of that New York. I moved out of New York in 1969 and it was a city that I never wanted to leave. I loved it here. I couldn’t imagine myself living anywhere else. When I started going back to Cincinnati about 10 years ago, I said, wow, this feels like New York, 1969. It feels affordable, right, for starters. And it feels — it felt very familiar to me. And it’s — I would say that it’s not necessarily a rejection of Hollywood. I would say it’s just a — it’s a quality of life issue for me.

MENENDEZ: I also think people are craving stories that don’t happen in L.A. and New York and Chicago.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right. That’s right. You know, and we tend to call them the flyover states. I call them the United States and I drive a lot. I’m a big driver. I mean —

MENENDEZ: Yes, you drove yourself to one of the film festivals in Canada.

ESTEVEZ: I did. I drove to Toronto. It was only a four-hour trip but I’ve made — I’ve got a 12-year-old car and it has about 280,000 miles on it. I’ve driven probably close to a million and a half miles in the United States alone. I make these long pilgrimages Across the Midwest and the South and end up in cities that most people have never heard of, towns people have never heard of, and really dig into those and spend time and get to know the people, get to know — Omaha, Nebraska. I love Omaha. They have one of the best farmers markets I’ve ever experienced in my life. Lawrence, Kansas, Marfa, Texas, some of these small towns that just have so much going on and we miss all that, of course, from 30,000 feet.

MENENDEZ: For someone who was not driven by fame, you found a lot of commercial success.

ESTEVEZ: Right.

MENENDEZ: The Breakfast Club, St. Elmo’s Fire, how have all of these experiences led to where you are today?

ESTEVEZ: Everything in your past informs where you ultimately arrive. I did do a lot of very commercial films. Oftentimes, I would do them for the wrong reasons or I would be talked into doing them. About 20 years ago, I made a left turn and I decided to make movies for me rather than for the studios. And that comes with a great cost, oftentimes financial and personal and — but I couldn’t continue seeing a resume that was not reflective of who I am.

MENENDEZ: Let’s talk about the way the film that you worked on with your father, what was that experience like?

ESTEVEZ: Well, any time you get to work with family, it’s really a double- edged sword.

MENENDEZ: I was about to say.

ESTEVEZ: Because you know how to push their buttons because you helped build the machine, right? So to be in Spain where my family came from, especially my father’s side, from the north of Spain, we are Gallegos, we’re from the area of Galicia, it was a real family affair to make that film. But perhaps even as equally important is the fact that the film has inspired tens of thousands of people to get off their couch and go walk 500 miles.

MENENDEZ: Just for someone who hasn’t seen it, just briefly tell me what “The Way” is about.

ESTEVEZ: Sure. “The Way”, it’s about a father who loses his son, who’s been out traveling the world. He left school and decided, I need to see the world rather than just simply study about it. And on the Camino de Santiago, he steps off the path in inclement weather and dies. The news travels back to the United States, my father, who plays the lead character, gets news of this, goes over to Spain to retrieve the body, to bring it home for — to the United States for burial and instead is inspired to do the Camino on behalf of his son. And he goes off with no training, no idea what he’s doing. And along this journey, he meets three other individuals and off to Santiago de Compostela they go where pilgrims and believers are told that that is where the remains of St. James the Apostle are buried. So this has been — pilgrims have been making this journey for over a thousand years but no one’s ever really made a movie about it until we went out, went over there in 2009 and did this.

MENENDEZ: It’s the 30th anniversary of The Breakfast Club. I want to roll a clip I bet you’ve never seen before.

ESTEVEZ: Probably not, no.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ESTEVEZ: I said, leave her alone.

JOHN NELSON, ACTOR, “THE BREAKFAST CLUB”: You going to make me?

ESTEVEZ: Yeah.

NELSON: You and how many of your friends?

ESTEVEZ: Just me. Just you and me. Two hits. Me hitting you, you hitting the floor. Any time you’re ready, pal.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: Well, you still got the hoodie.

ESTEVEZ: He did hit the floor, didn’t he, right?

MENENDEZ: Did you know when you were making this that it was going to be as iconic as it was?

ESTEVEZ: No idea. No. When you’re a young actor, you’re in a position oftentimes where you’re begging for work. The day that I auditioned for Breakfast Club, I auditioned for a commercial, a T.V. show, and probably another couple of films. So you just never know what film you’re going to — that they’re going to say yes to. When — I met John Hughes the year before that. I auditioned for 16 Candles and I auditioned for Molly Ring Wald’s love interest. And I nailed it and I was like, yes. And all of a sudden, I feel a hand on my shoulder and it’s the casting director and he says, “You’re not going to get this.” I said what do you mean? Everybody was talking about me. What are you talking about? He says, “Yeah, it’s not going to happen.” This doesn’t make any sense. Oh, you know, what? And I was furious and he says, “Listen, I need you to get in your car, you calm down first. I need you to get in your car and you’re going to drive over to Venice”, which is the seaside area in California, “and you’re going to audition for a film. ” “It’s an odd film”, he says, “but that’s the one I think you’re going to get. ” And it was Repo Man.

So I brought all of that anger and all of that frustration into the audition. And I was just like, man. And all I could think about was why and the director of Repo Man saw what I did in the room and said, I want to tap into that anger. And so again, you never know. Repo Man is iconic for — in its own way. Breakfast Club certainly keeps on having this extraordinary lifespan. Young people are discovering it for the first time. It’s very nostalgic for people of my age to watch and remember where they were when they first saw it.

MENENDEZ: You have been telling stories your entire life. You’re finally at a point where you get to tell the stories that you want to tell.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right.

MENENDEZ: The Public is now out in the world.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right.

MENENDEZ: What’s the story you want to tell next?

ESTEVEZ: Well, you know, I’m working on a lot of different things these days. There’s — I’m talking to a company about doing a series based on The Public because I think, again, there are thousands of stories to be told in — from the perspective of desk reference librarians. I think that there’s a lot of potential there. And it’s a show that you could move from city to city. So the first season might start in Cincinnati and then move the second season could be in New York or Seattle or Denver. So it’s got a lot of potential. So that’s one thing that I’m working on. I’ve been writing a script and working on a story about immigration for about 15 years and, of course, that’s not topical right now. So that’s something that I may be digging my teeth into as well.

MENENDEZ: Emilio, thank you so much.

ESTEVEZ: Thank you. Thank you. Thanks for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

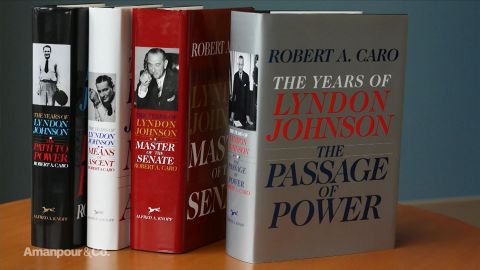

Robert Caro is perhaps America’s greatest living biographer, with his books on Lyndon Johnson and Robert Caro considered the definitive works on those men. Ayelet Gundar-Goshen is a prominent Israeli novelist and psychologist and joins the program to explore the fault lines and political narratives of her home country. Emilio Estevez joins to discuss “The Public” – which he wrote and directed.

LEARN MORE