Read Transcript EXPAND

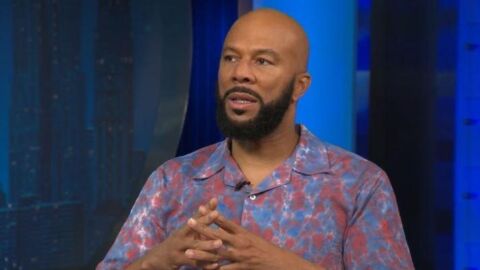

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And we turn now from all of this drama to the vulnerability of fatherhood. The Oscar Winning musician and actor, Common, real name Lonnie Rashid Lynne Jr. is best known for his Hollywood performances and chart- topping hits. But in his new memoir, “Let Love Have the Last Word,” Common documents his struggle to become a better father to his daughter and how he found the strength to speak out about his own childhood abuse. He spoke to our Alicia Menendez.

ALICIA MENENDEZ: Thank you so much for being here.

COMMON, AUTHOR, “LET LOVE HAVE THE LAST WORD”: Thank you for having me. I’m honored to be here.

MENENDEZ: So your memoir is out right now. The title is, “Let Love Have the Last Word.” What does that mean?

COMMON: I really believe that that concept and practice and title, I chose it because it’s so much going on in the world, people talk every day about the pains and the anxiety and the depression, and the divisiveness that I just learned that the thing that has kept me most solid, most hopeful, and most peaceful incented is love, and the practice of that. So, this book is about me working on myself.

MENENDEZ: One of the ways in which you are working on yourself has to do with your daughter. I mean your relationship with her forms the core of this book. Why did you choose to go there?

COMMON: My relationship with my daughter is really a good journey in practicing love because it’s a great example for me of ways where I thought I was doing the right thing and doing a good job at it, but somebody else has another perspective.

MENENDEZ: She had a lot of disappointments.

COMMON: She had a lot of — she had disappointments. She had hurt. And I thought I was, you know, doing a great job as a father, a good job as a father. I knew I wasn’t perfect, but I knew that I was giving her the love that she needed. But she saw it a different way and that’s what this book really started with that story or starts with that as part of the crux is because it is the example of, like, “oh, I’m loving you in the best way I can” but if that other individual, who happens to be my daughter, is not receiving that in that way, then I have to honor that.

MENENDEZ: What were her core complaints?

COMMON: Her core complaints were that I didn’t fight for her in certain situations where her mother was giving me resistance. That I didn’t — like, it was hard for her to see me when I was dating women if I was with another, you know, they had kids. To see me with someone else’s kids was very tough on her. And also, you know, she just said, man, I was gone a lot. And I had to tour and be on different — be in different places to even provide. And it was — it’s the real balance of understanding being able to do that and also making sure you’re at those — you’re there for someone.

MENENDEZ: She’s grown now. How old is she?

COMMON: Twenty-one. She’s graduating college.

MENENDEZ: So that’s a lot of life for her, a lot of career success that has happened for you in that time. In some ways, I felt reading the book like there is a cautionary tale about the price of fame and the price of success.

COMMON: I don’t think it’s one or the other, to be honest. I don’t think that you can’t pursue your dream. In fact, I encourage parents and people to be kind and loving to yourselves to follow your dreams. Because in fulfillment of that, you’ll be better to not only your child, but you’ll be better to everybody around you because you’re being better to yourself. I see so many parents that have been through situations where because they were having a child, they just gave up their passion.

And I don’t know — I know it’s difficult economics when it comes to I could pursue my passion and still have, you know, time for my child and make sure that it’s, you know, they’re being cared for if I’m not — I understand that it struggles, even just in the practical parts of that.

MENENDEZ: Well, because that’s true for you too. I mean you had a lot of years of hustle before you actually hit commercial success.

COMMON: Oh, man, yes. I mean, it’s — it was, you know, it was years where I’m like, OK, how am I going to pay for this mortgage, this car note, my daughter’s tuition? You know, the seasons of entertainment, like sometimes you’re just in the forefront and things are flowing well, and then sometimes it’s not. So I had those experiences to do that and the actual challenges of being able to take care of your family is one thing and then also saying, man, I have to be there.

And for me, it was like I was thinking that some of those important moments, I was never going to miss, but it’s the in-between moments too and those small moments that you still also have to find a balance to make sure you’re there for.

MENENDEZ: Part of writing a book about a topic as personal as love means you also had to go deep with yourself.

COMMON: Yes.

MENENDEZ: Unearthed childhood memories, childhood traumas. Can you tell us what happened to you?

COMMON: What occurred in the book that I talk about that occurred in my life was when I was around the age of 9-years-old and I was molested by a family friend. And I talk about it, and I talk about it in the way that I recognize that it was something that I had tucked away in my memories for a long time and didn’t even think about it, it really didn’t exist for a long time. And it came to surface when I was doing a film that was called “The Tale” that was about sexual abuse.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: You talked about the relationship, but this is a grown man.

LAURA DERN, ACTRESS, “THE TALE”: This was important to me and I’m trying to figure out why.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: And I recognized it. It was like, wow, this happened to me. It wasn’t — I have to be clear, it wasn’t like an ongoing thing. It was just one incident. And you know, acknowledging that incident was important for me because as I write in this book, I write this book for the healing of myself and for others and I want others to be able to feel safe to be in a space to open up to themselves and say — and figure out like if there’s some things that they want to deal with, that they’ve been through that’s caused trauma in their life to be able to be, like, man, I’m going to work on this, I’m going to heal myself from this.

So yes, I talk about it with the hopes of healing and forgiveness, to be honest. And I feel like this is the conversation that you don’t hear a lot from a black man, you don’t hear from men sometimes, especially the way it occurred.

MENENDEZ: Why? Why do you think that is?

COMMON: Because in culture, it’s — men are — we are taught to be like not as open or vulnerable. And within that conversation, you can feel some type of shame by telling that story or feel that you may get shamed about it.

MENENDEZ: That means something about you, that it happened to you.

COMMON: Yes, you can feel that and you feel that the ongoing thing, it could be something that people talk about that you don’t really necessarily want to always be identified by that. So you feel afraid to talk about it.

MENENDEZ: It’s a part of the book I would love for you to read. It’s on page 185.

COMMON: All right. “Thinking back, I should have gotten up from the bed and ran out of the room, but I felt a deep, sudden shame for what happened and for what he kept trying to make happen. As if I had brought it all on myself. I didn’t want to say anything to anyone and hoped that he would just leave me alone and go to sleep, which eventually he did once I fought back enough that he knew I was not going to touch him at all. Nothing else happened. The rest of the trip went on as planned. Everyone seemed happy, having a good time. I remember putting on the best face I could, but I was distant. Perhaps as distant as another planet feeling elsewhere within my own body. Ashamed of myself, and struck into silence, I said nothing to Brandon, to Ski, to my godmother, to no one. Most certainly not to my mother.”

MENENDEZ: So what I want to know, now that the story is out there, is how has your mom responded to it?

COMMON: My mother has been very open and caring. She — you know, it’s obviously something that she didn’t know about it and she wants to make sure that I’m all right. She knows it exists in so many facets of life because my mother is a teacher or former teacher, principal, and a great one at that. So she has had students who have experienced this from the neighborhoods that she taught in and was principal in. So, she — it wasn’t as shocking, probably, as some would think, but she definitely just listened to me and asked was — how was I feeling about the subject and I think she started processing it for herself. So, you know, my mother is one of my greatest supporters, definitely, one of my best friends, if not, my best friend in the world. So you know, she’s going to be there for me.

MENENDEZ: And your daughter?

COMMON: My daughter, she first found out about this, this situation, from a song. I felt this song was my way of sharing the story with her, and then we could talk about it. And when she heard it, she just took the headphones out of her ears and said, “this really happened to you?” And I said, yes, it did happen. She was like, “does grandma know? Does anybody know?” And I’m like, “no, they didn’t know but I did talk to her about it now.” And she, you know, she said, “wow, you’re very brave for saying this, dad and, like, I’m really proud of you.” She told me that just actually last night that she was proud of me for going out and talking about this and that — you know, that made me feel good.

And to me, the biggest hope would be with this and us even talking about this is that a child that has had — experienced that will feel like comfortable enough to talk to someone or feel strong enough or even if it’s the word is weak enough, feel OK to talk to someone who, you know, if they’ve experienced that.

MENENDEZ: A big part of your activism is present in your music. Just last year, you were at the Oscars for your song Stand Up for Something, which you wrote for the movie “Marshall.” At the event, you took a stand and you spoke up about the NRA.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: Tell the NRA, they in God’s way. And to the people of Parkland, we say, I say, sentiments of love for the people from Africa, Haiti, to Puerto Rico.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: What role do you see music playing in activism?

COMMON: Music is one of the most important roles because music gets the word out. It kind of is that subconscious soundtrack to the movement in many ways because sometimes there’s information in the music. I found, you know, through a lot of the music that I have digested, I’ve learned so much. Like through hip hop culture from the ’90s and ’80s, early, you know, mid-’80s, late ’80s to ’90s. I mean all that stuff planted seeds for some of the way I think and some of my consciousness. And along with that, the Bob Marley’s of the world, the Stevie Wonders, the Bob Dylans, the artists that speak up when it comes to social justice and just society, music has been that thing, Marvin Gaye. To this day, “What’s Going On” can speak to the times, right?

So — but I believe, let me say this, that the component of action has to go after the music. The music is the call. Like it’s like a coach huddling us up. Like let’s huddle, this is the plan. And then we got to go out and execute the plan.

MENENDEZ: Did your attitude about the connection between activism and your music — I mean, the early days of your career, you’re an underground rapper.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: The perseverance of a rebel, I drop heavier levels, it’s unseen or heard, a king with words, can’t knock the hustle. But I’ve seen street dreams deferred.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: And then finding commercial success. Was there ever anyone who said to you like it’s been great that you’ve been an activist up to this point, loved the socially conscious lyrics but now we’re going to do this commercial thing?

COMMON: Well, it was a time where early on in my career, the label that I was signed to were like, “Man, we need you to make some music that will get to the radio. We’re here to make money.” I was like OK, “well, let me try to compromise in a way and make a record that I’m going to write from the heart and make sure the music is something I think people will like.” That didn’t work. That was an aha moment, a shift in the paradigm for me to know that truth resonates and I feel like I need to be true to self and not only my art but just in anything that I do.

MENENDEZ: Well, it’s run through your music. It also now has run through your acting career. I mean when you are pursuing roles, choosing roles, how much of it is considering the message of the film and the message of the role?

COMMON: Well, I have to say, until I got to be a part of “Selma” —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDRE HOLLAND, ACTOR, “SELMA”: Reverend James Bevel.

COMMON: How you doing, ma’am?

NIECY NASH, ACTRESS, “SELMA”: I’m well. Thank you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: I didn’t know that I could really have that type of impact as far as acting would go, meaning being a part of films that did have some higher purpose, you know. And now, that has become — you know, that is like golden for me when I find a character or a role like the film “The Hate U Give,” I got to be a part of where it’s really has something to say. It sparks a conversation. That’s what I feel like I owe as an artist, as an actor, it’s like to at least be a part of art that sparks conversations.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: A lot goes through a cop’s mind when they pull someone over, especially if they have to get into a pissing contest with the driver about why they stopped him.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: “The Hate U Give,” you also sort of forced the viewer to reckon with a person we don’t often think about, which is the black police officer.

COMMON: The black police officer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: So if I think I see a gun, I don’t hesitate. I shoot.

AMANDLA STENBERG, ACTRESS, “THE HATE U GIVE”: Because you think you see a gun? You don’t say something first?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

COMMON: You know, I had to come to reckoning with it also. Because with all the murders and killings of young unarmed black men and women, it made me automatically have a certain position toward how I think the police treat us. And I do think my position is valid because it’s been proven with so many lives that are lost. But I also never thought about what a police officer who is not caught up in that mentality, what their lives may be like.

And that was a real great examination for me for, you know, the dynamics of what it is to be a black police officer. It gave me another perspective to at least be able to say, hey, when we come to the table and talk, we got to get — it’s an understanding we have to have, like we got to listen to each other, because every police officer is not out there to kill, and every black kid is not carrying a gun. So I think I wanted to just be a part of breaking that generalization and helping hopefully get people to the table.

MENENDEZ: Thank you so much.

COMMON: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

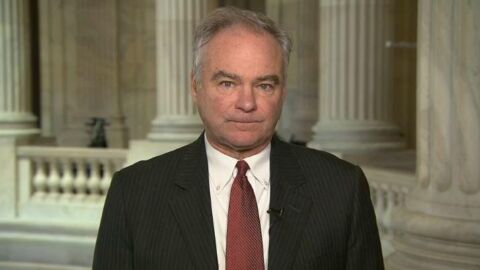

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Sen. Tom Cotton and Sen. Tim Kaine about the White House’s rhetoric against Iran. Alicia Menendez speaks with Common about his new memoir, “Let Love Have the Last Word.”

LEARN MORE