Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

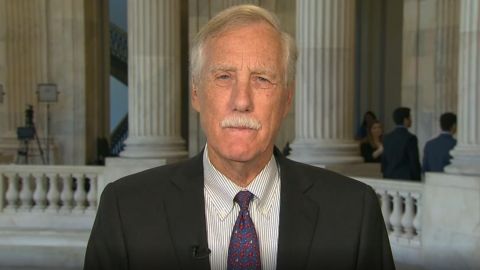

President Trump’s tariffs pivot back to Asia as China says it’s ready for a trade war and the cost mounts for everyday Americans. Senator Angus King

of Maine joins us.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MIKE HUNTER, OKLAHOMA ATTORNEY GENERAL: How did this happen? At the end of the day, Your Honor, I have a short, one-word answer. Greed.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Fighting Big Pharma over America’s opioid addiction. Will an Oklahoma case against the giant Johnson & Johnson set a precedent? I speak

to Andy Beshear, the attorney general of the hard hit state of Kentucky, and to a Yale law professor, Abby Glunt.

Then, the British are coming.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

RICK ATKINSON: I think understanding what our forebearers thought they were fighting for, what they thought they were creating, is important for

us to understand what we’re fighting for.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Pulitzer prizewinning historian, Rick Atkinson, with a different perspective on America’s revolutionary war.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

President Trump’s taste for tariffs isn’t going away. After threatening Mexican imports, the president is once again aiming his weapon of choice at

China, threatening another $300 billion of tariffs on their imports if President Xi doesn’t meet him to sort things out at the G20 summit at the

end of the month. While the Chinese are facing such threats head on. And here’s what a foreign ministry spokesman had to say today.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

GENG SHUANG, CHINESE FOREIGN MINISTER SPOKESMAN (through translator): China does not want to fight a trade war, but we are also not afraid of

fighting a trade war. If the U.S. is willing to hold talks on an equal footing, our door is open. If the U.S. only wants to escalate trade

frictions, we will resolutely respond and fight to the end.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And that is fighting talk. Though, U.S. tariffs would undoubtedly hit China hard, the retaliation from China can devastate

American industries and will pass higher costs on to the American consumers.

Maine lobster, for instance, is famous and the Chinese have developed quite a taste for it, but the state is feeling the pinch from China’s retaliatory

action. Maine’s senator, Angus King, bemoans the Trump administration’s handouts to the hard-hit but politically valuable farmers while his lobster

industry gets no such relief. And he joined me to talk about the right way and the wrong way to make China pay for its predatory practices.

Senator Angus King, welcome to the program.

SEN. ANGUS KING (I-ME): Good to be with you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: So, listen, I don’t want to sound frivolous but I mean, lobsters are something you are now lobbying for, particularly because it looks like

the China trade war is hitting one of your state’s main economic hubs and exports. What’s going on?

KING: Well, lobsters are collateral damage. It was one of the first tariffs that the — retaliatory tariffs that the Chinese imposed when we

imposed our tariffs. And I’m really trying to make a point here that the administration has decided that it’s going to pick winners and losers here.

They had a press conference where they’re giving away $16 billion to farmers in the Middle West who are affected by this trade war.

And yet, other businesses, other industries, other interests around the country are not being protected. Lobsters being one of them. Some of our

dealers have seen their sales fall something like 85 percent. China was our biggest growth in export market and now it’s fallen practically to zero

and the Canadians are taking over the business and they’ll have it into the future.

So, it’s just one of those examples of how this trade war is affecting Americans very directly and yet, only some people seem to be under

consideration for help.

AMANPOUR: Well, before I get to those other some people, let’s just talk about lobsters. I mean, honestly, I guess very few people would have

associated lobsters with, you know, a punch in the gut, economically, for your state.

Who knew that the Chinese middle-class love lobsters? They’re eating more and more. And that even president Trump served lobster to President Xi at

the White House. I hope it was Maine lobster. But paint a picture of proportionally what it does to your state. I mean, how many people are

involved in the lobster business, for instance?

KING: Well, it’s a — the business in total is about a $1.4 billion a year business in our state and that includes dealers, lobstermen, people along

the retail chain. There are thousands of lobster fishermen, they are essentially independent contractors, they own their own boats, they are

small business people.

Now, what these tariffs have done is affected dealers [13:05:00] who have been selling into China. So far, it hasn’t come back to hitting the boat

price but we feel that’s only a matter of time. If you lower demand substantially, you’re going to affect the price. So, it’s a long-term

threat.

And it’s not the only one, the problem is we’re facing competition from Canada, who has a free trade agreement with the E.U. on lobsters, which we

don’t enjoy. So, we’re at a disadvantage there. The steel tariffs affected the price of our steel lobster traps, and we’re also dealing with

protecting right whales. So, the lobster industry’s under quite a bit of strain right now and we don’t need additional tariffs that are going to cut

off one of our most important growth markets.

AMANPOUR: You know, it’s really interesting that you talk about the steel tariffs that the president’s imposed. And who — you know, I guess what

you’ve just illustrated is how all these issues are interconnected right down to the steel for the lobster pot.

So, you mentioned that there is — there are billions of dollars in handouts to the Midwest, to the farmers, 16 billion or so. What are you

asking for on behalf of the lobster industry?

KING: Well, we calculate that the losses on the exports are about $138 million. But what we are really looking for is some help from the

administration and expanding our markets. We don’t care whether we sell lobsters to the Chinese or the Japanese or the French, but we just want our

markets to grow and one way the administration could help us is in marketing assistance internationally that would make up for the loss of

this important market for us.

And I think it’s important to talk about the other effects of this. These tariffs are now — the federal reserve says they’re costing American

families about a $400 a year. It also happens to be that 40 percent of our families can’t afford a $400 emergency, and we’re talking if the tariffs go

to where they’re proposed, $800 a year per family. This is a big deal. This is a tax on Americans and I think we need to understand that this just

isn’t something that the Chinese are paying or somebody else. This is American consumers.

AMANPOUR: Well, let me just, since you put it in those terms, I just want to put it broader. The IMF estimates that some $455 billion in global GDP

could be lost and global economic output down by 0.5 percent by 2020 due to this trade war. President Trump again called tariffs a beautiful thing

this week.

What would you say to him? I mean, there you were all together at D-Day, in this incredible show of bipartisanship and, you know, commemorating and

celebrating the true heroism of all that liberated Europe. What would you say to him on calling a trade war and tariffs a beautiful thing?

KING: Well, I mean, tariffs are a tax on American consumers. The idea that China’s paying the tariffs just isn’t true. Somebody picks up a good

at the Port of Long Beach and they have to pay an import duty, usually it’s the importer. That gets passed along to the sales all the way along the

chain and ends up a tax on the American consumer. That’s been verified by pretty much everybody. The president keeps saying China’s paying the

tariffs. That’s really not the case.

Now, having said all that, China needed to be confronted and I concede that, that China was not a good actor on the world stage in terms of theft

of intellectual property, subsidies, requiring joint ventures in their country. They needed to be confronted. The question is, how do you do it

and do you do it step by step or you do it through what amounts to international shock therapy?

And the president’s made a big gamble here. If he’s successful, if China concedes and fundamentally changes their business model, that will be a

huge win for the entire world. If, on the other hand, this drags on for a number of years, as you say, it’s going to hit global GDP, it’s certainly

going to hit American GDP and it’s going to hit ordinary Americans in the wallet.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And you do make a good point that everybody agrees with, the idea of the intellectual property theft, the whole cyber, you know,

adventurism, the Huawei, all of these things, as you say. But I guess expand then on what is the right way to do this and to achieve those goals

and comment, if you would, on president Trump’s seeming to use tariffs as a punishment for a variety of different things, such as the immigration

situation, the migrant situation south of the border. He threatened to put those tariffs on Mexico, for the moment, that’s staved off, for the moment,

and his own party doesn’t like it. I mean, can you comment on using tariffs for a whole broad array of foreign policy goals?

KING: I think it’s bad policy. I think tariffs [13:10:00] should be used sparingly, history tells us that tariffs generally are not a positive

force, they’re always retaliated and you end up with some kind of an escalation, just as we’re seeing with China. I mean, go back to the Smoot-

Hawley Tariff in the early ’30s which most economists feel contributed significantly to the great depression worldwide because each country sort

of shut down its borders.

Trade can be beneficial. It has to be within bounds, it has to be according to norms and rules. So, using tariffs to bludgeon another

country — here’s the other problem with the president’s approach to tariffs, it’s indiscriminate in terms of affecting everybody. An effective

way to deal with China, for example, would be for a unified front against China’s predatory trade practices involving Mexico, Europe, South America,

other parts of the world and instead, we’ve picked fights with all of them.

So, we find ourselves essentially without allies in this major confrontation. The major way we could influence Chinese behavior, I think,

is if everyone in the world said, “We’re not going to deal with this. We’re not going to tolerate this.” And again, separate issues like

intellectual property theft from commercial interests.

The president likes tariffs. If you go back to the ’80s he was writing — he thinks tariffs are good, they’re protective. History tells us

otherwise. And to use them for policy reasons, I think, risks alienating our allies and ultimately, being self-defeating in terms of their effects

on the American people.

AMANPOUR: So, look, we’re two years in or so to this whole tariff situation, and you remember very early on, he said trade wars are easy to

win.

KING: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Where do you see the ledger right now? With the proviso that if China does change its behavior, it is a big win.

KING: Well, there’s another factor involved here, and I was in Asia two weeks ago and talked to a lot of the leaders and people — places like

Singapore and Japan. Part of what we’re not understanding is Chinese history, and the Chinese are coming out of a period of what they call 200

years of humiliation at the West. They’re very sensitive to insults, to bullying, to pressure, and there’s a — they feel a kind of national pride

which makes it all the more difficult for them to give into us in this situation beyond just the matters of the narrow tariffs. So, that’s one of

my concerns is that we’re not approaching this in a way that’s liable to have the Chinese really make the kind of changes that are necessary.

If you want a prediction, Christiane, here’s what I think is going to happen. The Chinese will make some concessions, they’ll buy more soybeans,

they’ll do a couple of other things, they may make a promise about intellectual property. The president will declare victory, the tariffs

will go away and we’ll go on much as before. That’s what I think is going to happen if we hold out for sort of total victory, unconditional

surrender, however you want to define it, I think the Chinese are unlikely to capitulate in that manner, in part because of their commercial interests

but also in part because of national pride and they are rightful — what they feel is their rightful place in the world.

So, we’ll see how it plays out but it’s a high stakes game right now. And to go back to lobsters, American consumers, American businesses happen to

be in the crosshairs.

AMANPOUR: You successfully lobbied for a lobster emoji. I mean, what did you write? You said a new lobster emoji —

KING: I did. It’s right here on my tie.

AMANPOUR: There you go. It would fill a necessary and unique void in the current emoji list and should it be added appears destined for significant

usage by lobster fans around the world. I can tell you, I just used a lobster emoji, got nothing to do with this interview and I have you to

thank.

KING: Well, that’s it. We pushed for it, we got it. It was — some of my friends said, “Aren’t you doing anything else down there?” This was

actually a kind of a sideline to get this done but it happened. And listen, anything that promotes business in Maine, I’m for.

AMANPOUR: Let me ask you about another thing that you are very, very concerned with. You just talked about the threats and one of them are, you

know, the cyber threats. You are chair of the newly established Cyberspace Solarium Commission, it was named for President Eisenhower and what he did,

that project in 1953.

The mission is to review cyber threats. But here’s a scary quote from you, “At this moment, we do not have a clear strategy to prevent bad actors from

attacking our vital infrastructure. And with each passing moment of inaction, the risk grows graver. I deeply believe that the next crippling

attack on our country will be a cyber-attack.”

You know, we’ve also heard from Former Defense Secretary Ash Carter that [13:15:00] the — you know, the Defense Department and the U.S. doesn’t

have the right connections and contacts in Silicon Valley and this whole industry. What are you most scared of?

KING: Well, it’s really hard to say. I can tell you that the director of National Intelligence every year does a worldwide threat assessment.

Number one this year was cyber. It could be the electric grid. It could be our elections in 2020. It could be the financial system. It could be

our telecommunications system. We’re the most wired society on earth and therefore we’re the most vulnerable to this kind of attack.

And my concern and the work that we’re doing, we just had a meeting yesterday of our commission, the work that we’re doing is to try to get the

country to the place where we have a public, known cyber doctrine and strategy that will provide some level of deterrence to our adversaries.

Because right now, we’re a cheap date, Christiane. We’re — you know, they can attack us, they can go after our elections, there are really no

consequences and therefore, they’re going to keep doing it. And so, what we’re working on, on our commission, is how do we defend ourselves more

effectively because this really is the frontier of, you can call it competition or you can call it warfare, it’s something in between. We are

facing potentially catastrophic attacks and if we keep sort of wishing it away, we’re going to be in deep trouble.

And that’s why, by the way, you mentioned briefly Huawei. Huawei makes — you know, they’re very skillful, they make a product that’s involved in the

5G network, but they’re also in cahoots with the Chinese government. and if they’re the key building block of 5G, which is going to be an enormously

— an enormous change in the way our society works, if everything is connected through a device that’s connected to Beijing, that’s just, you

know, waving the white flag. I think it’s a huge mistake and it’s one that we’ve got to persuade the rest of the world that it’s not worth getting

cheaper devices if you’re exchanging your national security.

AMANPOUR: We have been delving into the opioid crisis, the addiction crisis and accountability for Big Pharma. Now, Maine is the latest to join

states who are suing Purdue Pharma, the makers of oxycontin. And in 2017, you had one of the highest levels of opioid addiction deaths, 417. It’s

going down a little bit. But what do you make of these cases like in Kentucky and Oklahoma, this one that you want to bring, your state wants to

bring against Purdue Pharma? Where do you think this is headed?

KING: I think the people that largely contributed to this should be held accountable. I just literally an hour ago met with a woman in my office

whose brother recently committed suicide because of, in part, brought on by opioid addiction, which started with a sore hand and a set of pills that he

was prescribed and he became addicted and it destroyed his life.

This is a national tragedy, it’s striking in many ways most violently in rural states, that’s why Maine, New Hampshire, West Virginia are being

particularly hard-hit. And I think the people that made money on this and I believe, and this is going to be played out in court, had knowledge of

the addictive nature of their products but pushed them anyway, need to be held accountable.

So, the judges and the juries will make the final decisions but if you cause harm to somebody and you knew it was at least foreseeable, being held

accountable is the — is very important, in my view. This is a tragedy for our country. As you said in Maine, we’re still losing more than one person

a day in our state to this scourge and it’s awful.

AMANPOUR: It really is and the way you describe that individual case resonates across the country. Senator Angus King, thank you for joining

us.

KING: Thank you, Christiane, a pleasure to be with you.

AMANPOUR: And now, we’re going to focus on the opioid crisis because it is a national one. The numbers are staggering, more than 130 deaths every

single day according to the Centers for Disease Control. And like Maine, now, several states are trying to hold Big Pharma accountable in court.

Closely watched right now is the multibillion-dollar case brought against one of the world’s biggest drug makers, Johnson & Johnson, by the state of

Oklahoma. It accuses the company of manufacturing a public health crisis by overmarketing painkillers and downplaying the health risks. It’s the

first public trial to come from 2,000 opioid lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies which have settled out of court, mostly.

Watching from the sidelines with a keen eye is Kentucky’s attorney general, Andy Beshear. His state has been devastated by the crisis, and he’s

joining us from Louisville. Also, with us is Abbe Gluck, a Yale [13:20:00] law professor who served on several major health law cases, and she’s

joining us from New York.

Welcome to both of you.

Let me ask you first, Attorney General, because you are also, you know, got these cases going on. Just tell us what is the state of play or the state

of affairs, the tragedy, in your own state and the legal redress that you’re seeking there.

ANDY BESHEAR, KENTUCKY ATTORNEY GENERAL: Well, this opioid epidemic is the challenge and the crisis of our lifetime. We lose 30 Kentuckians a week to

a fatal overdose. Those are 30 of our family members and our friends that we lose every single week. We have over 100 babies born a month addicted

to opioids. And it’s not just deaths or addiction, it’s tearing at the very fabric of our families. We have more kids in kinship care and foster

care than ever before.

So, this is truly an epidemic and a crisis in our very future depends on it. And we, like Oklahoma, believe that the makers and the distributors of

these opioids knew exactly what they were doing. These are highly addictive substances that shouldn’t have been prescribed or marketed for so

many of the folks out there now suffering from addiction. We shouldn’t have had the hundreds of millions of pills flooding into small communities

where in many times we see more than a couple hundred opioids being prescribed for every man, woman and child in a small eastern or western

Kentucky County.

AMANPOUR: Right. And —

BESHEAR: And the costs of what we face are so significant and that’s why we have filed over nine lawsuits just from my office alone, including

against Johnson & Johnson and Janssen.

AMANPOUR: So, you know, you describe the state of affairs there. I mean, it is — your death rate is more than double the national average. But so,

does this Oklahoma case against Johnson & Johnson, is — how important is this and why, for you, and for others trying to use the courts now instead

of just out of court settlements and payouts?

BESHEAR: It’s important because it’s one of the first cases to go to trial where the public is going to hear about the actions of this company

specifically. And Oklahoma, like Kentucky, alleges that they knew how dangerous these drugs were but they marketed them as “rarely addictive” and

they even marketed them towards seniors, telling them that this would improve life and again, would rarely be addictive if used for chronic pain.

It’s important because the truth is finally starting to come out. And what we’re going to see is that greed drove these multinational companies to

flood our communities with substances that are causing thousands of deaths and tearing apart our family.

AMANPOUR: Abbe, I want to ask you because you’ve served as co-counsel on some of these health law cases and you — you know, you’re watching the

sort of broader impact around the country. How important is it to — and how likely is it that it’s going to be successful in court because the

others, whether it’s Purdue Pharma, whether it’s Teva Pharmaceuticals, they’ve settled out of court. Purdue, $270 million in March, the other

one, $85 million in May. Why is it so important to do it this way now?

ABBE GLUCK, PROFESSOR, YALE LAW SCHOOL: Well, it’s important to Oklahoma. The Oklahoma attorney general is showing his constituents that he is being

responsive to their concerns, being responsive to public safety. But it’s also important, all of these suits, whether it’s a settlement or whether

it’s the court trial, are important because they’re going to have an impact on the 2,000 other cases that are pending, whether those are Kentucky’s

cases or the 1,600 cases that are aggregated together currently in a federal district court in Cleveland.

For a long time, we’ve been watching that federal district court in Cleveland. We’ve been waiting for a huge mega settlement to come out of

those cases. And what’s happening in Oklahoma is setting the tone. It’s showing the public has an appetite for justice in these cases, and it’s

also giving us the sense of the kind of numbers that are coming out.

So, we’ve seen the kind of numbers that are coming out from settlements, which you just mentioned, and now we’re going to see the kind of numbers

that might come out from a trial. Johnson & Johnson took a gamble here, going to trial in front of the world in a televised courtroom. They could

have a huge victory or they could have a huge defeat, and that’s going to set a tone for everything that follows.

AMANPOUR: Well, you just hit the nail on the head. And I want to play the opening statement or at least part of it from the Oklahoma attorney

general.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HUNTER: Our evidence will show that 4,653 Oklahomans died of unintentional overdoses involving prescription opioids [13:25:00] from 2007 to 2017. The

pain, anguish and heartbreak that Oklahoma families, businesses, communities and individual Oklahomans is almost impossible to comprehend.

How did this happen? At the end of the day, your honor, I have a short, one-word answer. Greed.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, I just want to follow up on what you said, Abbe. You said it’s a high-risk strategy. I’d like to ask both of you after you see that

part of the, you know, opening statement, how risky is it? Because you know, I mean, they have — I mean, they’re using this public nuisance kind

of defense — or not defense, you know, but charge and that’s usually used, apparently, in property disputes. So, to both of you, I would just like

you to comment on the public nuisance first. Abbe, quickly, before I turn to the attorney general.

GLUCK: Sure. Public nuisance, you are correct, is an unusual cause of action in this kind of case. Normally it’s used for things like, you know,

property damage or damage to public spaces. It’s been used unsuccessfully in the gun litigation and it’s never been used successfully in sales cases,

because those cases are very intangible and it’s very hard to trace the chain of causation from the person who sells an item to the abuse and

diversion of that item.

In this case, the Oklahoma attorney general made a strategy call. He went forward on this public nuisance claim because it seemed that the judge was

receptive to it. And by dropping all the other claims in the case, he was able to get the case tried early and quick out in front of that huge

federal multidistrict litigation. Going first is very important, you get a piece of the pie first, assets here are limited. Going first gives you a

huge sort of fronted runner’s advantage, and I think that’s part of what’s motivating the public nuisance claim here.

AMANPOUR: And from your perspective, Attorney General Beshear, I mean, you must be sitting on the edge of your seat, your colleague in the State of

Oklahoma is taking a high risk, I mean, it’s a gamble. Where do you see, legally, the public nuisance defense being used?

BESHEAR: Well I hope to take every single one of my cases to trial because the people of my state, my people, deserve to have this trial in one of

their regions, that they can come to the courthouse and watch while these companies have to explain themselves.

I don’t think there’s a significant risk, certainly in our cases, at all because we not only have a public nuisance claim, but we have significant

misrepresentation claims. These are companies that were selling these drugs on the false claims that they weren’t going to cause addiction. And

just look at what’s happened, look at the death, the destruction, the addiction, the cost, the families torn apart, I mean, this is absolutely

ripping my state and every other state apart.

And I’ll just give you an example. This weekend, I’m going to an event by a group that calls themselves Northern Kentucky Hates Heroin. This started

about five years ago with a small group of mothers and fathers that had lost their children. Now, that group is nearly five times larger today.

I’m proud of what the Oklahoma attorney general is doing because we’re all in this together. It doesn’t matter if you’re a Democrat or a Republican

or an Independent, drugs will kill you just the same.

So, I’m glad he is getting this information out there. I’m glad that the public can truly hear and learn about the actions, and I believe he’s going

to be successful, just like we’re going to be successful in each and every one of our lawsuits because when you’re Kentucky, you’ve got to be

aggressive.

Now, when you look at the devastation that’s been caused in my state, we can’t sit behind larger states and some national settlement. We have to

get out there and fight for the resources that we need to rebuild because we were hit that much harder than just about anybody else.

AMANPOUR: And what — just quickly before I go to the companies themselves and what they’re saying, just quickly, Attorney General Beshear, what

figure are you looking at? I mean, how hard have you been hit? What do you need to redress and rectify what’s happened to your state and the

people there?

BESHEAR: Well, you know, no amount of money is ever going to bring somebody’s child back. And every single day I work with and talk with

parents or — that have lost children or children that have lost parents. You know, every single time one of these fatal overdoses occurs, it tears

apart a community. We are all victims at this point, and that’s the starting point that we’re never going to be able to bring somebody back.

But what we do need is the dollars for prevention.

[13:30:00] If we can stop new addiction, then we have hope for tomorrow. What we need is enough money to make sure every single person who wants

treatment has a bed and doesn’t have to wait for it and we have the different types of treatment that will work. With some, it will be

medically assisted. With some, it’s 12 step.

We need men’s, women’s and adolescent treatment because it’s all different. And then we need dollars for recovery because once you’ve fallen into

addiction, staying in recovery is hard.

It takes extra help along the way. You may have transportation issues.

We’ve got to make sure we can find you a good job. We’ve got to eventually get your record expunged so you can get back into society.

We’ve got to repair your relationship with your family because addiction and these drugs cause all of those issues. And so while I don’t have a

specific number in mind, I will tell you that it is substantial because the devastation is severe.

But I believe that if we can hold these companies accountable, that we can take a drug epidemic that has arisen in our lifetime and put it behind us

in our lifetime. And as a dad of an 8 and a 9-year-old, now that’s the type of legacy that I want to leave for my kids and everybody else’s.

AMANPOUR: Well, it certainly is urgent but as you can imagine, the drug companies are pushing back. So Abbe, let me just read you, for instance,

Johnson & Johnson.

Their attorney has said when they make the charge, i.e., the State of Oklahoma, that the people at Janssen set out to addict kids, it is only

fair that we bring before the court what Janssen actually does to educate kids. Now, Janssen Pharmaceuticals is the Johnson & Johnson subsidiary

which is accused of flooding the state with these highly addictive painkillers.

But here’s what they’re saying, that this is, you know, it’s FDA regulated, it’s approved, these opioids are not like weird illegal drugs that are

flooding. They are legal and FDA regulated and approved.

So, does that make it more difficult, Abbe, do you think, to bring them to court, so to speak, to bring these drugs to court, which are legal?

GLUCK: Yes, of course. So, the fact that the FDA approves opioids, that they have a valid, necessary medical use in many situations, makes these

cases very different from, say, tobacco.

That’s what is complicated in the litigation strategy in these cases. At the same time, the plaintiffs and governments like the attorney general,

they are making the argument that even if you got FDA approval, even if opioids were sometimes validly prescribed, the companies nevertheless

engaged in deceptive marketing practices.

They knew the drugs were more addictive than they let on. They aggressively targeted vulnerable populations seeking to get more people

addicted.

That’s why you’re seeing claims like fraud brought in a lot of states, consumer fraud, consumer statutory claims in addition to the public

nuisance claim because the crux of the cases have to be against these companies not that the drug itself was dangerous because it was FDA

approved but because the companies knew it was more dangerous than they let on, and they went and took advantage of that.

AMANPOUR: So let me just ask you this, then, because fentanyl is part of this whole thing. Now, fentanyl is about 100 times more powerful than

morphine, 50 times more potent than heroin. And Johnson & Johnson’s opioid products at the center of the trial that’s ongoing are a tablet called

Nucynta and a fentanyl patch called Duragesic.

Now, why would a company like Johnson & Johnson, which by the way, we all remember went over and above and created, you know, really redressed one of

the early issues? Do you remember, the Tylenol crisis, they came out and they really fixed it and they changed the caps and all the rest of it.

Why would a company like this that’s family friendly even get into the fentanyl patch business and how dangerous do you see that, Attorney General

Beshear, the fentanyl growth?

BESHEAR: Well, I think the fentanyl growth is incredibly dangerous. And when you think about the FDA, what you have to look at is what they approve

these drugs for.

I believe these opioids were meant as God’s grace at the end of life. That if you have terminal cancer, you shouldn’t have to go out in pain but these

companies decided they weren’t going to make enough money off what the FDA had approved the drugs for.

And so what they engaged in is significant marketing to get doctors and others to prescribe them for what we call off label uses, things like

migraines where no one should ever be taking an opioid and that’s how our markets got flooded.

But you know, I think these cases boil down to something pretty simple. It’s that I was raised to believe that I’m responsible for what I say.

And what these companies repeatedly said while marketing these drugs is that they weren’t addictive, that they wouldn’t cause harm, that they were

safe for seniors, that they were safe for [13:35:00] active servicemen and women and what happened?

You know, my friend, Emily Walton, lost her son, T.J., three days before he was going to deploy to the Kentucky National Guard. Why? Because he took

medication that the company told him would help him.

At the end of the day, we’re all responsible for what we’ve done and what we’ve said and we’re going to hold these companies accountable for what

they’ve done and said.

AMANPOUR: So, very quickly to you Abbe, because we’ve got very few seconds left. The threat of bankruptcy of some of these companies, and that has

happened after settlements and things, how — you know, how urgent is it to get these settlements, to get this accountability before people start

declaring bankruptcy and then there’s no money in the kitty?

GLUCK: Well, I think the issue is bankruptcy would provide for an orderly distribution of assets, given how many cases there are. It isn’t really

fair to have a race to the courthouse.

It wouldn’t be fair, for instance, if Oklahoma took all of Johnson & Johnson’s assets and left nothing for Kentucky, for example. So what a

bankruptcy filing would do, and I do think we’re likely to see some more bankruptcy filings, is it would pause all of the different litigations and

bring all of the claims before a single judge for orderly and hopefully fair distribution of the assets.

If a company has more assets than necessary to settle or trial of these cases, great. But I think for many of these companies, that’s going to be

a challenge. And if the assets are limited, bankruptcy may be the most fair way to make sure that people get paid.

AMANPOUR: All right. It’s really a huge task but it’s so interesting to hear you both. Abbe Gluck and Attorney General Beshear, thank you so much.

Now, as America grapples with political discord, our next guest says the nation’s founding history holds the key to today’s challenges. Rick

Atkinson is a Pulitzer Prize-Winning Historian who delved deep into King George III’s archives to write his new book “The British Are Coming.”

It’s the first installment of his planned American revolution trilogy. He walked our Walter Isaacson through the key players in America’s war of

independence.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON, CNNI CONTRIBUTOR: Rick, welcome to the show.

RICK ATKINSON, AUTHOR, THE BRITISH ARE COMING: Thank you, Walter.

ISAACSON: Thank you very much. You know what really blew me away is the notion of you going through the archives of George III, King George, and

Windsor. Had anybody ever tapped those archives before?

ATKINSON: You know, surprisingly, not really. There were 350,000 pages of Georgian in documents and the queen, Queen Elizabeth II, owns them and she

decided in 2016 that she was going to open them up to scholars.

I was one of the first ones in and to have them digitized so they would be preserved in perpetuity. And most of those Georgian papers are from George

III because he was king for 60 years.

So every day, I would show my badge at the Henry VIII gate and show my badge at the Norman gate and climb 102 stone steps and then 21 wooden

stairs and you’d be in the garret of the round tower built by William the Conqueror in the 11th Century. And that’s where the papers are kept.

And they’re fantastic. George was his own secretary until late in life when he began to go blind. And so he not only wrote his correspondence

himself, he wrote the copies and there’s a real tactile sense of being in his presence.

And he’s a great list maker. He would write lists. He would write formulas for insecticide, for example, and theater reviews.

And he would write lists of all of his regiments in North America and he would list the — a number of officers, the number of musicians, the number

of rank and file. You can see his arithmetic scratching in the side as he does his sums.

So I spent a month there in April of 2016 and really felt like I got to know him and felt like I, you know, he’s not the bumbling nitwit we see

mincing across the stage in “Hamilton.” He’s much more a man of parts and has a greater depth than we Americans particularly have generally assigned

to him. And he is running the train in the American revolution.

ISAACSON: And in your book, “The British Are Coming,” you’re able to do it from both vantage points, from the vantage point of the American colonists

fighting as well as the British. And one of the interesting things about George III is that he was much more of a hardliner than we thought before.

ATKINSON: This is so true. And you know, when the revolution began in April 1775 and for some months thereafter, Americans wanted to believe that

he was, if not an innocent bystander, that he was fundamentally on their side and that’s not true at all.

He was, in fact, a hardliner. He was the force behind the hardliners within the cabinet. Lord North, he was his first minister, prime minister,

really had no appetite to be a war minister and was not particularly interested in prosecuting a war for eight years across 3,000 miles of open

ocean in the age of sail.

And George is the one who’s constantly bucking him up. And George is the one who’s saying, blows must decide. And George is the one who is not

necessarily drawing up [13:40:00] the minutia of which battalions are going where but he’s very involved in the nitty-gritty of expeditionary warfare.

ISAACSON: Why? Why was George III so intent on pursuing a war against the colonies, in their war of independence?

ATKINSON: Yes, why, why, why, why? Indeed. I think the fundamental reason, Walter, is that he becomes king in 1760. In 1763, the first

British empire is created with British victory in the seven years’ war, French and Indian War as we call it.

They gained enormous territorial benefits from that victory. They get Canada. They get Sugar Islands in the West Indies. They get parts of

India. They get a billion fertile acres west of the Appalachians.

And George is Determined that he’s going to hang on to that empire and he also believes, and this is an article of faith within the cabinet and

certainly for him, that if the American colonies are permitted to break away, if the insurrection succeeds, then Ireland is next, Canada, the Sugar

Islands, India, and that the empire will dissolve.

It will be the end of Britain as a great power, a newly created great power. And it’s a strategic misconception. It’s — they’re badly

informed. This is not true.

And yet, it really is the underpinnings of their determination to thwart American independence and to suppress, bloodily, the revolution.

ISAACSON: Could it have been avoided if they had found some more commonwealth-type structure?

ATKINSON: Yes, you know, commonwealth, I think, is the obvious answer but it wasn’t obvious in 1775. There were lots of negotiations.

Benjamin Franklin was in London, as you well know, for years before he left in the spring of 1775, trying to find a modus vivendi, trying to

accommodate both the British point of view and the colonial points of view.

And I think positions are just hardened too much by that time. And so it just kind of unravels and once the shooting starts, then it’s very

difficult to put the vase back together once it’s smashed.

ISAACSON: That was a Ben Franklin line. And, of course, he and his own son end up on different sides of the revolution. How common was that, that

Americans were divided on whether or not they wanted independence?

ATKINSON: Yes. Yes. I mean, you know well, it’s one of the great tragedies of the war. His beloved son, William, who is the Royal Governor

of New Jersey and he’s, you know, he’s participated with his father in some of the experiments and the kite flying and all the rest of it.

And Ben Franklin talks about his happiest period of his life and he remains loyal. He does not become radicalized the way his father has over time in

London and refuses to accede to fatherly advice that you need to get on the — you need to get on the side of the angels here.

And, of course, he’s ultimately arrested, he’s imprisoned in New England. It’s really a tragedy. It’s quite common, this schism within families as a

consequence of irreconcilable political differences.

It really anticipated the civil war in that sense. This is a civil war, the revolution is, and it anticipates the civil war of the 19th century in

the way that it fractures families.

ISAACSON: You call it a civil war and one of the themes of your book is you treat it as a civil war as opposed to just a war for independence.

What do you mean by that?

ATKINSON: Yes. Well, you know, you can guess and scholars have calculated that 18 percent to 20 percent of the 2 million white Americans in the

colonies at the time of the revolution are loyal.

Now, loyalty is a shifting concept. You may be loyal if the Royal — if the British Army’s in your backyard and when they leave, you may be less

loyal, particularly if your rebel neighbors are warning you that you’re going to be punished.

But say 18 percent are loyal. Enough of them are loyal to form regiments, to fight, to support the king’s army and the Royal Navy, and to do the

bidding of the ministers in London.

And so it’s a civil war in the sense that there actually is armed conflict between Americans. If you’re a loyalist, the treatment you’re likely to

receive from the rebels can be atrocious.

You can have your lands confiscated, you can be jailed, you can be sent into exile, you can be executed in some cases. It’s a very harsh

treatment.

Some of the loyalists were put on skulls in the Hudson River below all beneath [13:45:00] in dire conditions. Some were lowered by windless 70

feet below ground in an old Connecticut copper mine to these rock-walled cells known as hell.

It was really a harsh treatment and it went back and forth. The loyalists sometimes persecuted their rebel neighbors. So, it’s a civil war in the

most fundamental sense.

ISAACSON: Why was Washington such a great leader?

ATKINSON: He’s not a particularly good general, I think, it has to be said. He’s not a tactician. He’s a lot like Dwight Eisenhower in some

ways.

He doesn’t see the battlefield spatially and temporally the way a great captain does, a Napoleon and he’s got a steep learning curve. When he

takes over the continental army on July 2, 1775, in Cambridge outside of Boston, he’s been out of uniform for 17 years.

And in the five years that he was in uniform, you know, he’s a colonel in the Virginia Militia. He’s always under British superior commanders.

There are a lot of things he does not know.

As he acknowledges, he does not know how to run a continental army. He doesn’t know much about artillery. He doesn’t know much about cavalry so

we start with the understanding that he makes a lot of mistakes on the battlefield.

He’s got his moments. There’s no doubt about that, but he makes a lot of mistakes. He’s also got a lot to learn about the army that he’s

commanding.

He shows up in New England as a Virginian commanding mostly New Englanders in this continental army and he is fairly disparaging of the New

Englanders. He writes about the dirty New Englanders and he has nothing good to say about the officers serving under him from New England.

And it takes a while for him to understand, first of all, that he is someone who has scores of slaves and overseers back in Mt. Vernon taking

care of business for him while he’s away, has trouble understanding the sacrifice made by men who leave their farms, their shops, their families,

to come serve at his side in the cause.

He doesn’t really get that at first. The army, the continental army, is the absolutely critical institution in this young republic aborning. It’s

the indispensable institution and he is the indispensable man within it.

And for the two of them to figure out how they fit together is going to take some time. Having said all that, he’s a great man. He’s a great man

who’s worthy of our adulation and all the things that we think about him if we will acknowledge that there are some issues.

When he dies, there are more than 300 slaves at Mt. Vernon. You cannot square that circle morally. Nevertheless, he embodies traits that I think

should be the north star for all of us to this day, a sense of probity, a sense of commitment to a cause larger than himself, dignity.

These are things we should demand in our leaders. These are things we should demand of ourselves. These are things that we should recognize in

Washington and celebrate to this day.

He can seem alabaster. He can seem remote and he’s not really. He’s got a three-dimensional quality that is really riveting and it’s important for us

to remember that.

He’s not just this distant figure who has been embalmed in reverence. He’s a fantastic person to help launch us on our journey.

ISAACSON: One of the other great generals in the book and actually far more colorful in a way is Charles Lee.

ATKINSON: Yes.

ISAACSON: Tell me about Charles Lee and what would have happened had there been no Washington. Would Charles Lee have been the one in charge and how

would it have been different?

ATKINSON: Yes. Well, it would have been really different and probably not as good. Charles Lee was a British Army officer. He ascended to the rank

of lieutenant colonel which is a fairly high rank in the British Army.

He’d seen some combat. He’d been in America in the French and Indian War. He had been shot in the chest and survived that.

Here’s a colorful guy, he’s a weird-looking guy by all accounts. He’s tall and spindly, the people describe him as having no shoulders.

I mean he has an enormous nose. He accumulates many nicknames, one of which the cruelest of which is Nazo. He has a great affection for dogs.

He likes dogs as he acknowledges much better than people. He’s always got a pack of dogs around him.

He decides he’s going to emigrate. He becomes disaffected with his life in the British Army. He comes to America a couple of years before the

revolution begins.

He’s a radical at heart and he writes and speaks eloquently about the power of the ideas that are germinating in America, about potential independence

[13:50:00] but distance from the crown. And he writes powerfully about the — his assertion that this rather ragtag, badly armed, badly led, badly fed

army in the making can hold their own against the British Army, one of the finest armies in the country.

And this falls on welcome ears. The political leadership and other military officers are pleased to hear this. He’s made a general, major

general, and he soon becomes second in command to Washington.

He — Washington listens to him carefully because he knows things that Washington does not, and practical things about how to organize a bivouac

and how to organize artillery and how to get men to do what you want them to do and how to do other things that Washington is really pretty green at

all this.

Unfortunately, he’s also very ambitious. So we see him successfully in command, on the scene when the British send the Royal Navy to try to take

Charleston in June 1775. They’re repulsed in a very bloody and surprising defeat for the Royal Navy.

Lee is the commander at the time. And he’s celebrated through the colonies for this clubbing of the Royal Navy and he begins to think that maybe, in

fact, Washington’s having his problems, Washington’s going through a succession of defeats, that maybe what the country needs is Charles Lee as

the commander in chief.

He has a very disloyal correspondence with one of Washington’s aides, Joseph Reid, who’s a lawyer from Philadelphia. Washington opens a letter

by mistake from Lee to Reed and discovers that, in fact, these guys are conspiring behind his back. He’s deeply wounded by it.

When Washington retreats across New Jersey in December of 1775 — ’76, after being badly slapped around in New York, Lee has a wing of the army,

Washington’s pleading with him to join the army, Lee’s taking his time, he’s corresponding with members of Congress, he’s forming the beginnings of

a cabal.

He makes a really serious mistake. And on one night in mid-December, 1776, he decides that he’s not going to camp that night as he’s moving to join

Washington in Pennsylvania and he goes to a tavern, spends the night.

There’s a British cavalry patrol that gets wind that he’s there, they attack this tavern early in the morning and they captured him. Washington,

who by this point is shrewd enough to recognize that Charles Lee is a big problem for him, writes this very deaf letter to Lee in jail in New York

saying, “Gee, I’m sorry about this. I can only hope that someone in your circumstance can be as happy as you might be in this circumstance.”

It’s really Lee is later exchanged, he comes back, he joins the Army, disgraces himself in battle later. He’s really finished as a force. But

he’s got a role early on and he’s a wonderful character to write about.

ISAACSON: Underlying this book sort of the foundational truths that helped create America, what do you think those truths are and how are we wrestling

with them today?

ATKINSON: Well, first of all, I think the concept of truth is true. We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that

they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights.

OK, that’s foundational and it’s asserted that it is true. And you know what? It’s not true because all men are not created equal in 1775.

Those fine words did not apply to 500,000 black slaves. They don’t apply to women. They don’t apply to Native Americans. They don’t apply to

indigents.

It’s aspirational. As great Yale Historian Edmund Morgan wrote, “It doesn’t guarantee men these basic rights, it invites them to claim them.”

And I think that that is the essence of what we see in those who are fighting for independence from Britain at the time. It’s aspirational.

They recognize that there are issues to be worked out and it turns out there are issues to be worked out for 243 years subsequently.

We’re working them out still. Archibald MacLeish, the poet, and librarian of Congress said, “Democracy is not a thing that’s done. It’s a thing a

nation must be doing.”

And I just think it’s [13:55:00] very important to remember that, that we have — we’ve inherited this extraordinary political legacy, but it’s a

work in progress and it’s always going to be. I think understanding what our forbearers thought they were fighting for, what they thought they were

going — creating is important for us to understand that what we’re fighting for, what we are continuing to create, I just think it’s important

to affirm it every day.

ISAACSON: Thank you so very much for being with us.

ATKINSON: Thank you, Walter.

ISAACSON: Appreciate it.

ATKINSON: Thanks.

ISAACSON: Thanks.

(END VIDEO TAPE)

AMANPOUR: Fascinating insights into the revolutionary past and the book, of course, is out now.

And that is it for our program tonight.

Thank you for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS.

Join us again tomorrow night.

END