Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

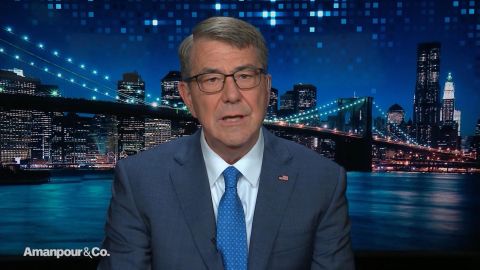

ASH CARTER, AUTHOR, “INSIDE THE FIVE-SIDED BOX”: I’m not sure the current president listens to the secretary of defense.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

Former Defense Secretary Ash Carter tells me what it takes to run the Pentagon and why he believes China and Russia are this administration’s

biggest foreign policy challengers.

Then, celebrating 80 years of gospel and soul. Music legend, Mavis Staples, on why she is still trying to sing America together.

And later —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

FRANK RICH, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER, “VEEP” AND “SUCCESSION”: There’s certain – – the truths about power in Washington, about the cynicism of politicians and the people around them as they grasp for power that just hold up and —

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Producer, Frank Rich, tells us all about “Veep,” the smash hit comedy which sheds a brutal light on political game playing in Washington.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

The horizon is crammed with security challenges, not least the escalation tensioning with Iran. And the United States is sending ever more military

forces while having no defense secretary, following General Mattis’ resignation in January.

In May, President Trump nominated the acting secretary of defense, Patrick Shanahan, for the job. But this week, he withdrew his nomination due to a

domestic violence incident and he’s being replaced by Mark Esper, secretary of the army.

Now, the need for strong leadership at the Pentagon is something my next guest understands all too well. Ash Carter served as secretary of defense

under President Obama and he’s worked inside the Pentagon on and off for the past 35 years. His new book “Inside the Five-Sided Box” sheds light on

the complex inner workings of the organization and it offers a blueprint for defense in ever changing world. And he joins me from New York to talk

about it.

Secretary Carter, welcome back to our program.

CARTER: Good to be here with you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: So, you got this new book out and it’s really looking at leadership and particularly, concentrating on your time at the Pentagon.

And you make a blanket declaration so that we all know where you stand, “I love this Pentagon. I love this organization, warts and all.”

Why do you feel the need to say that? What are the warts?

CARTER: It’s got 240 years old. So, it’s got traditions and people tend to think of the place as stogie (ph) but — and there’s a certain part of

tradition that is really good. But, also, the Pentagon is something I was proud of, this is not a wart, a learning organization.

Let me give you a couple of examples. Counter insurgent and counter IED. Obviously, we were caught flatfooted on them initially and we had to learn

how to do better, we got really excellent (ph). It does have warts. There some ways in which we are still haven’t made the transition strategically

where we need to go from the era of our preoccupation with counter- terrorism and counter-insurgency to our — the need to focus on China and Russia and the high end.

We haven’t yet linked ourselves to the tech community completely, which is an important part of our future in continuing to be the most

technologically advanced military in the world. We have — we’re not — we haven’t dipped into all the pools of talent that we need and all volunteer

forces.

You may not know, Christiane, for example, that a large number of our recruits come from just six states in the United States.

AMANPOUR: Wow.

CARTER: And it means there are 44 states where we haven’t got enough presence yet. So, there are a lot of things and this is what I — one of

the things I describe in the book, there are a lot of managerial issues. And, you know, you think about the secretary of defense being in the

situation room or helping the president make decisions, that’s a piece of the job but it’s just a piece of the job.

AMANPOUR: Right.

CARTER: You’re running the largest organization in the world and your secretary of defense not only of today but of tomorrow. I got make sure I

leave to my successor the excellence that I received from my predecessors.

AMANPOUR: OK.

CARTER: So, you’re working against the future all the time.

AMANPOUR: But I wonder, you are a theoretical physicist, I believe, by training and background.

CARTER: Yes.

AMANPOUR: So, you are thoroughly steeped in the fact-based world. And I guess you make your decisions on facts and evidence. How difficult is it?

Because you write about this in your book. You talk about how difficult it is to make informed and fact-based decisions and matters of policy in these

highly emotional [13:05:00], as you call them, victriolic (ph) political times. What are the key issues that you see?

CARTER: Well, you know, you’ve got to make it clear to all of your subordinates, you have to set an example that I expect from you not only

good conduct and professionalism but also the truth. And you need to, therefore, stick up for your subordinates when they do the right thing or

say the right thing.

I was lucky, all the times I was involved in Republican or Democratic administrations that there were presidents who were all very smart and they

took their responsibilities seriously and they would read and study.

I remember Bill Perry coming back from a meeting when he was secretary of defense with Bill Clinton and he said, “It’s so embarrassing,” he says,

“Clinton is always the best prepared person in the room.” And I had President Obama also, when I was actually secretary of defense, as somebody

who was demanding and didn’t suffer fools easily at all. So, you need the appetite at the top. And I don’t — I haven’t worked under the current

president. I don’t quite see that appetite. And, of course, he talks casually about the truth and whether it matters or not.

AMANPOUR: Would you serve the current president?

CARTER: I don’t — no. I don’t think I could. It’s completely hypothetical, I haven’t been asked. But I think not because I — you have

to believe you can help. Your first duty as cabinet member is to help the president to succeed. This is a president who doesn’t seem to listen to

his cabinet members. And so, it doesn’t look like I would be getting in a situation that I would be helpful.

I also have to say, this is a separate matter, I don’t like all of his conduct.

AMANPOUR: Well, let me ask you, because the idea of being a loyal soldier, so to speak, and being a helpful constructive member of a cabinet is an

interesting line and interesting needle to threat. So, you, when you were in the Reagan administration, you criticized quite publicly the center

piece of Reagan’s military in the Cold War, which was to Star Wars Program.

What was the reaction to you for doing that and how does a secretary of defense thread the needle between disagreeing and dissenting and being

accused of treason and either — you know, and shutting up?

CARTER: Well, there was a little of that when I published my report on Star Wars, people say, “Well, this is the president’s policy. How can you

say it’s not scientifically correct?” Which just wasn’t. I would like to build a missile defense based on lasers, but we didn’t know how. By the

way, we still don’t know how.

But there was another side to it. It wasn’t considered partisan death for anybody. The scientific community stayed loyal to me and supportive of me.

But more importantly, I worked after that for Paul Nitze who is President Reagan’s arms control negotiator. It wasn’t regarded that — dissent was

regarded, provided it was based on fact and truth that it was done respectfully, as a respectable contribution. It didn’t disbar you from

public life.

So, that was a time that I hope is not bygone where partisanship didn’t matter in that sense and people who are running national security

understood there would be a debate.

AMANPOUR: And I guess I want to ask you, then because you bring up Russia and China and these other issues as strategic threats for the future.

Let’s talk about Russia. Under President Obama and clearly under President Trump, it’s been a ban major issue. I want to know how you assess what

consumes and motivates President Putin. You’ve written about it in your book.

CARTER: Yes. Well, I — as it turns out, I met him for the first time in 1993. So, I’ve had the opportunity to observe him. He was a note taker

for Boris Yeltsin in the summit and I was an assistant secretary of defense. But I’ve observed him in all those years.

And one thing, Christiane, about Vladimir Putin is he says what he means and says what he’s thinking. So, you can read what he says and you

probably do that, as well. And I understand where he’s coming from. He laments the end of the Soviet Union. He thinks the United States has made

mistake after mistake by toppling governments without any idea what is going to replace them afterwards. So, he says all this stuff. And I don’t

agree with all those positions but I understand them.

Where it’s hard to work with Vladimir Putin is he sets it as a Russian goal to frustrate the United States. Now, how do you hold talks with somebody

over their desire to frustrate you? That’s not a place. That’s not Syria. It’s not arms control. It’s not nonproliferation. We can discuss these

issues and, you know, agree to disagree where we disagree, work together where we [13:10:00] agree. But it’s hard to build bridge to a guy who is

out to frustrate you.

AMANPOUR: When you say frustrate, I think you mean, in fact, challenge America’s presence and its influence around the world.

CARTER: Act as a foil.

AMANPOUR: Act as a foil, exactly. And I wonder whether this is even doubly troubling because you also, and other actually, have said that even

though they’re not bosom buddies and they don’t always view the world through the same lens, China and Russia are having these same thoughts

about America.

CARTER: They are. I don’t, myself, really buy the prospect of them working all that closely together. We’ve been afraid of that for a long

time. Russia and China are very different, they have different interests, very different futures. The only thing they agree on is the desire to

challenge the United States, but they do it for different reasons.

And so, they’ll — you know, they’ll both be challenging us. I don’t see them forming a block or (INAUDIBLE). But you’re right, China has an agenda

and you can talk to them about their agenda. I understand where they want to go. They’re a communist dictatorship, number one, they want to keep

that going. And number two, they want to spread their economic and maybe increasingly political influence around the world, which I don’t want to

see happen, but it’s certainly an understandable objective.

They don’t set themselves the goal of screwing the United States, per se. They set themselves the goal of establishing themselves as an equal and

maybe someday superior to the United States. They’re a little bit easier to work in those objectives. They’re both competitors. But it’s that

aspect of Putin that is kind of spiteful that makes it particularly difficult.

AMANPOUR: That’s interesting because clearly China, though, has been the main big power in the cross hairs of this administration, tariffs, the

trade war, pulling out of the TPP, all those things. I mean, obviously angry about the theft of intellectual property, worried about Huawei,

worried about the territorial ambitions in the South China sea, et cetera.

You have said that you regret pulling out of the TPP because in some way, to you, it’s as valuable, if not more than an aircraft carrier in the

region.

CARTER: Yes. It had strategic importance. I mean, let’s remember, importantly, everything you said about China is right, I agree with that.

China is, however, only half the economy and half the population of Asia. So, there are a lot of countries there that collectively are very important

to us and TPP was an effort to, first of all, enlist them with us in establishing trade rules with China. And by abandoning TPP, you leave the

world to a network of bilateral trade relations.

Now, think of how that feels if you’re a small Southeast Asian country and you’re negotiating with China bilaterally and there’s no rules, it’s all

about force, and you have a communist dictatorship against you that is huge and that can bring like communistic dictatorships can, the political, the

military and economic, all to bear down on you, you don’t stand a chance in that environment. And that means that these trading partners, which are

half of Asia, are put at a disadvantage with respect to us. So, that’s why TPP was a good thing.

And, you know, it’s gone now. So, we can’t cry over spilled milk. But it’s why some multilateralism has to go along with bilateralism in trade

relations. Bilateralism is the Chinese playing field. It’s not our playing field. You don’t leave the playing field to the opponent or the

competitor.

AMANPOUR: Would you agree that, in fact, it was under the president you served, Barack Obama, that the idea of deterrence and red lines has been

rendered meaningless no matter what you think about intervention not in Syria, putting a red line by the United States of America and then not

enforcing it reduces your credibility and your deterrence?

CARTER: Now, I think if we could go back and do it over again or if I had been secretary of defense and been able to advise President Obama at the

time, even if he decided to accept this Russian deal where they get rid of the chemical weapons, which was the issue, without us having to carry out

the strikes that we had planned, by the way. I was deputy secretary of defense. So, I was in a decision-making mode but I was ready to go and I

thought we were going to go that night, down in size (ph), down at the engine room.

AMANPOUR: Wow.

CARTER: But if you’re not going to do that, in order to not suffer the strategic harm that you’re talking about, the loss of reputation, you have

to go out and explain. And one of the things President Obama was great in many, many ways [13:15:00], and I don’t want to be too negative or give the

wrong impression, but it was not his strength. When he thought he had done something right, he thought explaining that to somebody who didn’t get it,

was kind of a waste of his time.

And I think that in this case, you had — you know, you had just done something that really surprised the rest of the world, you better have a

good explanation for that. Otherwise, the surprise — it’s not going to be judged on the merits, it’s going to be judged on the appearance. And he’s

a merits-based kind of guy. And that’s respectable. But in public life, sometimes you have to worry about appearance as well.

AMANPOUR: Wow. That’s fascinating insight. It really is. I just want to sort of end in the Middle East. We understand the tensions with Iran. Who

knows what is going to happen there. But I want to ask you about Saudi Arabia because you’ve been in the room around the current crown prince,

Mohammad bin Salman.

CARTER: Many times.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And so, I would like you to tell us, the U.S. under President Trump seems to put all its eggs in this Saudi basket right now in

terms of Middle East security and Middle East policy. And you have said that you feel that they haven’t proved themselves to be reliable or

competent military allies and that he himself doesn’t seem to be massively prepared.

CARTER: Well, yes. They — Saudis will constantly say, you know, “What a wonderful thing it is to have them as friends and allies.” And it’s nice

to have them as friends and allies but, first of all, oil isn’t what it used to be. Second of all, I appreciate that they buy our arms, but

realistically, they have no other choice. And they pay for them and we give them. It’s a transaction. It’s equal. It’s not a favor to us.

And when it comes to us asking them to do something as a partner, I’m sorry to say, they haven’t come through. For example, I asked Mohammad bin

Salman, I met with him many, many times and many conversations with him and tried to have a good working relationship with, would he do something about

ISIS and they never did anything about ISIS.

Instead, they — if you remember, they declared a coalition one day without telling anybody else in the Islamic world that they were starting an

Islamic coalition, which was a good idea, but this was a ready, fire, aim kind of initiative. And so, their performance hasn’t always been what they

suggest it’s been. And I’m not trying to be too hard on them, I’m trying to be realistic.

Don’t tell me that this is a relationship in which they give much more than they get. That’s just not the case. And I think we ought to reset the

relationship a little bit and ask more and demand more of Saudi Arabia.

AMANPOUR: Here you are again going back to your theoretical physicist background. I just want to ask you what you make of the miniseries

“Chernobyl,” which is taking the world by storm. And we’re seeing in real time how the Soviet Union lied about what was going on, how these people,

from the firemen to the scientists to the reactor personnel to civilians, didn’t know what was happening and then tried to do everything they could

to mitigate what was an enormous catastrophe. Just talk about that.

CARTER: Well, I remember those days. A friend of mine, who was Yevgeny Velekoff (ph), who is the guy that Gorbachev put in charge of the clean-up,

I remember them flying helicopters over it, dropping boarded concrete and so forth. And I remember the lies and the cover up. But that was the

Soviet Union then. You spent time in the Soviet Union back in those days. And I think this documentary is so realistic.

And so, all the sets and everything are so Soviet. It takes me back to those times. And I remember and I knew a lot of those people who did that.

I was pretty young yet but I had relationships with their scientific community.

And there’s one moment I’ll never forget that was reported in the “New York Times,” where a “New York Times” reporter goes out on the train station,

(INAUDIBLE) in Kiev. And there’s a guy with his whole family and all their belongings packed up waiting for the train. And the reporter goes up to

him and says, “Why are you leaving Kiev? The government says everything is OK and the Politburo is arriving in Ukraine.” And the guy looks at the

“New York times” reporter and says, “If it’s bad enough for them to come, it’s bad enough for me to go.” That was the Soviet Union.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Amazing. Ash Carter, former secretary of defense, thank you so much for joining me.

CARTER: Good to be with you, as always, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: And now, something to soothe the soul [13:00:00], Mavis Staples has been singing gospel music since she was eight years. She performed in

front of America’s most iconic leaders like Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy, and her powerful vocals provided a soundtrack to the Civil Rights

Movement.

In 1999, she and her family band, The Staple Singers, were inducted into the rock and roll hall of fame. And in 2016, she became a Kennedy Center

lifetime honorary. It’s one of the highest accolades in American culture.

This year, as Mavis gets ready to turn 80, she’s out with a new album “We Get By.” She’s had an extraordinary life and career. And as I heard, she

has no plans to slow down.

Mavis Staples, welcome to the program.

MAVIS STAPLES, GOSPEL AND R&B SINGER: Well, thank you for having me. It’s an honor.

AMANPOUR: Thank you. You’re about to turn 80 years old. Nobody would tell by looking at you, by the way. And you’ve been a professional

musician all your life just about. Was there ever a time that you doubted the course your life has taken?

STAPLES: Well, no, not really. I’ve had a few stumbles, you know, but I always kept the faith that everything would be all right. So, I’ve been

just fine.

AMANPOUR: And tell me how it all began for you, before you became famous and being — you know, singing with your family. Where was the first Mavis

Staples performance for instance?

STAPLES: The first performance was at my uncle’s church in Chicago. Actually, my father started us singing because he was disgusted with the

group that he was singing with. Well, he was singing with all male group, the “Trumpet Jubilees.” And these guys, there were six of them. They

wouldn’t come to rehearsal. Pops would go to rehearsal. There might be three. The next time he go to rehearsal, it might be three.

So, he was so disgusted. He came home one night and he went in the closet, pulled this little guitar out of the closet and called us children into the

living room, set us on the floor in a circle and began giving us voices to sing, then he and his sisters and brothers would sing when they were in

Mississippi.

AMANPOUR: Wow.

STAPLES: And — yes, yes. One night, my Aunt Katy (ph) lived with us and she came through and we were on the floor rehearsing and she said, “Shucks.

You all sound pretty good. I believe I want you to sing at the church on Sunday.” And, oh, we were so happy we were going to sing someplace other

than our living room floor.

AMANPOUR: It just sound so nice. What about your — the family? Who are — let’s meet the Staples, for instance. Who were the family kids around

you?

STAPLES: The family was my father, Pops Staples, my sister, Cleotha Staples, my sister, Yvonne, and my brother, Pervis, and of course, me.

That was the “Staples Singers.” Pops taught us the song — the very first song he taught us was “Will the Circle be Unbroken.”

We sang that at my uncle’s church that Sunday and the people wouldn’t let us sit down. We didn’t know what encore meant. They kept clapping and

somebody told us, “They want to hear you again.” So, we ended up singing that song three times because it was the only song that Pops had taught us

all the way through.

You know, so, Pops says, “Shucks. We’re going home and learn some more songs. These people like us.” And that was the beginning of the “Staples

Singers.”

AMANPOUR: It’s pretty amazing. But just tell me, also, how you became the lead. I think it has something to do with your brother and his voice

changing.

STAPLES: Yes, indeed. My brother, Pervis, he sang the lead. Pervis’s voice was like Michael Jackson’s voice, real high but he could really sing,

you know. And I was singing baritone. My father — overnight, it seemed that Pervis’s voice changed and got really heavy.

So, Pops, says, “Mavis, you’re going to have to sing the lead.” For some reason, the lord blessed me, where my voice, I could sing high and low.

And I told Pops, I said, “No, daddy. I don’t want to sing lead. I think I want to sing baritone.” I thought baritone was the most beautiful voice in

the group. He kept telling me, he said, “Mavis, you have to sing lead because Pervis can’t get up there high anymore. You have to sing.” And he

— I kept saying, “No, no, no, no, Pops.”

He had a little piece of leather about the length of a ruler he had cut, you know, and that was to get my little legs when I was bad, you know. And

I saw him reaching for that piece of leather and I said, “OK. OK, daddy. I’ll sing. I’ll sing lead.” And that — from that [13:25:00] time on, I

was singing the lead.

AMANPOUR: Let just me play a little bit of a gospel song you sang, “Uncloudy Day.” Let’s play a little bit of that.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(SINGING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Mavis, it’s really incredible and I can see you rocking and swinging there. I mean, it sounds like a very, very professional mature

voice. How old were you?

STAPLES: I was 13 years old then.

AMANPOUR: Wow.

STAPLES: I had just turned 13. Yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean, that sounds like a much more grown up voice.

STAPLES: Yes. I was — well, I get my voice too from my mother’s side of the family. My mother and her mother, my grandmother, they had very strong

voices. As you know, Pops — now, I get the music ability from Pops because Pops’ voice was really high and smooth, you know, and — so, I was

blessed. That’s my gift, my voice.

But, you know, we would fool people. The people — when we started traveling, the disc jockeys would say, “That’s little Mavis Staples singing

that part of that song,” and people would say, “That’s not a little girl. That’s got to be a man or a big fat lady. That — no little girl has a

voice like that.”

AMANPOUR: Let me just ask you, you grew up in Chicago but your father’s roots were in Mississippi, right?

STAPLES: Right.

AMANPOUR: How did Mississippi enter your repertoire?

STAPLES: My father would send Yvonne and I to Mississippi to stay with my grandmother so he could have some help, you know. And we would go to

Mississippi, in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, an all-Black town, you know. And I went to school. I was the May queen. I would fight a lot in Mississippi

because the kids would tease me a lot. You know, they tell me I sounded like a boy. My voice was so heavy. And I would get into fights.

But Mississippi, we would walk every Sunday to my grandmother’s church in Merigold, and that had to be about eight miles from her house. And

Mississippi was — meant a whole lot to me. My father would take us back down there to Dockery Farm and show us — he showed us where he proposed to

my mother and he would show us where he grew up as a boy.

AMANPOUR: And just I want to ask you about that sort of period of your life. I mean, you toured the segregated south a lot, and that must have

been quite difficult and very challenging. And your father said that your mission, as a group, was, “Our aim is to get across a message while we’re

entertaining people.” Tell me how that mission statement, you know, played out, especially in some of the really difficult areas during the Civil

Rights Movement.

STAPLES: Oh, we were — you know, the songs, the people, when we would sing, they loved it. They needed that. They needed those messages that we

were singing. And the Civil Rights Movement — we started singing freedom songs and writing freedom songs because we had heard Dr. King’s message.

And my father told us one day, you know, “If he can preach this message, we can sing it.” Our voices were like the soundtrack of the Civil Rights

Movement. We would march, we would sing. And Congressman John Lewis, he told me — he wrote my line of notes for my freedom album that I made with

Ry Cooder. He said, “Baby, your family kept us going. Kept us motivated. By singing your songs, you all inspired us to keep going.” You know, we

were just happy. We were happy doing what we were doing.

AMANPOUR: You know, you say that you were the soundtrack, and that’s indeed right, that’s what so many people say. But your father himself

said, “If you want to write songs for the “Staples Singers,” well, just look at the headlines.” So, one of them you did, “Why Am I Treated so

Bad.” Watching the news one night —

STAPLES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — you saw the “Little Rock Nine,” which was that tragedy of the nine children locked out of Little Rock Central High School during the

desegregation times. He wrote a song.

STAPLES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: We’re going to play a little bit of it, OK.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(SINGING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

[13:30:00]

AMANPOUR: So the video, obviously, is from a later performance but nonetheless, that song came from that time. What was it like? Did you

feel, I don’t know, any responsibility? You played, I think, for Dr. King, right?

STAPLES: Yes. And that particular song was Dr. King’s favorite. We would sing before he would speak. At all of the meetings, we would sing before

Dr. King would speak.

And every night that we were on our way to the church or the auditorium, wherever we would be, he would tell Pops, he’s saying, “Now, Staple, you’re

going to sing my song tonight, right?” And Pops would say, “Oh, yes, doctor. We’re going to sing your song.” And that was “Why Am I Treated So

Bad.”

I felt very sad for a lot of times for people like the Little Rock Nine. Watching those children try to go to school and board that bus.

These children walked every day. Every morning, they would have their books in their arms.

They would walk into a crowd of people who would throw rocks at them. They were spat upon and calling them names but they kept their heads high and

they walked with their books to that bus that they wanted to board.

It went on for so long, the mayor of Little Rock, the governor of Arkansas, and the president of the United States to let those children go to school.

And this particular day that they were going to board the bus, we were watching and all of a sudden they get all the way up to the bus and the

policeman put his Billy club across the door and wouldn’t let them go.

And that was when Pops said, “Now, why are they doing that? Why are they treating them so bad?” And he wrote that song that evening, “Why Am I

Treated So Bad.”

I’ve had the opportunity to meet some of the Little Rock Nine. In fact, in Detroit, I remember two of them came to our concert and they have followed

us just like we were following them.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Mavis, I wonder what it is about your music and the music of that era, what is it about the lyrics and the beat and the rhythm that

was so absolutely suited the Civil Rights Movement?

STAPLES: Yes. Well, you see the lyrics, the lyrics are truth. When you’re singing the truth, people when they’re hearing truth, they’ll

respond to it.

That’s what they want. They want to hear songs of truth. They want to hear it.

And we get told all the time of our harmonies. We were sounding like — a lot of people when we first went on the road, they thought we were old

people.

We were little kids. We were a little stair steps. But people thought we were old.

And I guess it kind of reminded them, too, of when they were young and they were hearing these sounds. Sister Mahalia Jackson was just the — sister

Mahalia Jackson was the very first female voice that I heard.

And her voice moved me into the living room where my father was playing it. And he told me who she was.

I just fell in love with her. And she was my idol. She inspired me.

So sister Mahalia, Ruth Davis from the Davis Sisters and Dorothy Love Coates from the Gospel Harmony. These were three ladies that inspired me.

AMANPOUR: Fast forward a few years, you also eventually formed sort of a professional relationship with Bob Dylan. You entered a different group of

singers and musicians.

How close were you to Bob Dylan? Tell us.

STAPLES: Well, Bobby and I, we were very close. We were in love with each other but we had to — Bobby wanted to get married. He desperately wanted

to get married.

And I had to keep telling him — turning him down because we were too young. I knew I was too young. He didn’t think we were too young but I

was too young.

I wasn’t 20 years old. And he just — that was the very first day that I met him that he proposed, you know, but he had been hearing us all the

time.

Because his manager told them, “Bob, I want you to meet the [13:35:00] Staple Singers.” And he said “I know the Staple Singers. I’ve been

knowing the Staple Singers since I was 12-years-old.”

So my father said, “How do you know us so well?” He said, “I listen to Randy.” And Randy was a station — 50,000 watts station that everybody

listened to Randy.

And he even quoted a verse of a song that I was singing. He said, “Mavis, she sings rough. You know, Pops, you have a velvety voice, a smooth

velvety voice.” But Mavis, she gets rough sometimes.”

Mavis — he quoted the verse. He said, Mavis young to come on David when there’s rock and slain. I don’t want immediately.”

He’s a dangerous man. And boy, we just couldn’t get over Dylan. And, you know, finally they went into the concert, he was singing and Pops said,

wait you all, listen to what that kid is saying.

And Bobby was saying how many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man? And Pops would tell us stories about how he would walk down the

street in Mississippi and if a white man was coming toward him on the same side of the street, he’d have to cross over. He couldn’t walk on the same

side.

So he said we can sing that song. And we went back home to Chicago. We bought Dylan’s albums and we learned “Blowing in the Wind.”

AMANPOUR: There’s quite a lot of crossover between the freedom songs you were singing and the freedom songs that he was singing in another

generation. So it’s actually really interesting.

STAPLES: That’s right.

AMANPOUR: Yes. I wonder what you feel like that you have continued and even in your latest album, you’re singing about faith, you’re singing about

freedom and love. And whether that will continue, I mean you don’t sound like you have any intention of slowing up at all.

STAPLES: Oh, no. No. I still have plenty of work to do.

Things are worse today than they were in the ’60s. So no, I can’t slow down. I can’t stop.

I’ve got work to do and I’ve got a lot of messages to deliver and I intend to as long as I can. That’s what I plan on doing.

AMANPOUR: We’ll all be listening. Mavis Staples, thank you so much, indeed.

STAPLES: Oh, you all are going to be listening? Thank you. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: And while Mavis Staples represents the best of America, Selina Meyer, title character of HBO series “Veep” may well represent the worst.

And that’s according to Frank Rich, its executive producer.

The award-winning show now over after seven seasons is well-known and well- loved for its biting satire of Washington and its cynical parodies of politics and theater.

Themes that are also the cornerstone of his other series “Succession” that is loosely based on the Murdoch family where Machiavellian family members

vie for power of a media empire.

Frank Rich sat down with our Walter Isaacson to discuss the fine lines he’s treading between fact and fiction.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON, CONTRIBUTOR: Frank, welcome to the show. And congratulations on “Succession” which is getting renewed on HBO for next

season.

FRANK RICH: Well, thanks a lot, Walter. It’s great to be talking with you again.

ISAACSON: All these years of looking at the intersection of theater and politics, I loved your memoir “Ghost Light” which is about growing up in

Washington, loving power, theater, politics, that, you know, confluence.

And that’s what we’re kind of seeing in these T.V. shows you’re now doing like “Veep” and “Succession.”

RICH: It’s interesting. I haven’t quite — yes, it’s sort of happenstance but you’re right.

I mean I think in the case of “Veep”, it really conveyed my feelings about Washington, growing up there, being an outsider because my family wasn’t in

politics but living in the city. And yes, so it’s great to sort of distill it.

“Veep” reflects Julia Louis-Dreyfus’s ideas about D.C. We grew up not far from each other.

And then “Succession”, yes, it’s about media power. It’s also about family to a great extent which I also understand and families that can be

difficult.

But yes, it’s sort of amazing to me that I’ve been able to play out some of my passions in the world of fiction, not just journalism.

ISAACSON: But you’re also playing out some of the experiences that we keep having. And the amazing thing about “Veep” is every new episode is

something we’ve been dealing with.

In fact, I want to show a clip, if we can.

RICH: Sure.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SELINA MEYER: OK, Leon, [13:40:00] I’m not sure about this part where I say “I want to be president for all Americans.” I mean, do I? You know,

all of them?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: How about real Americans?

MEYER: Oh, yes, that’s good. And then we can figure out what I mean later.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Ma’am, I don’t have a copy of the speech.

MEYER: OK, I don’t know what she’s saying so here.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Ma’am, the voters need to know clearly and definitively why you want to be president in your own words.

MEYER: If you want me to use my own god damn words, then write me something to say, OK?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, ma’am.

MEYER: Oh, and take out the stuff about immigration because I feel it’s a little too issuey.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: OK.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ISAACSON: How do you adapt something that is happening in the real world and get it into a show like that so quickly?

RICH: Well, the concept of the show from the beginning from Armando Iannucci created and continued by the later showrunner Dave Mandel is we

never mention a political party, we never mention any living politician.

We only mentioned one later than Bragen. And yet, there are certain truths about power in Washington, about the cynicism of politicians and the people

around them as they grasp for power that just hold up.

And, you know, I feel — it’s weird. We’ve had the situation where we’ve created actual storylines that then come true in real life. But that

wasn’t our intention.

ISAACSON: What happens when something that is absurd that you’re doing on the show comes true in real life? And how do you keep up with the

absurdity we’re living?

RICH: We’re in the can. We have to air what we have but we did try in the final season which just aired to make it a little bit darker, make the

humor even darker than it was to recognize at least unofficially, you know, the culture has changed under Trump.

And so — but we never mentioned Trump or Obama or anybody. But that ratcheted up so much we had to also ratchet our humor and stories up to

capture this moment.

ISAACSON: You say it tells us a little bit about power and how it operates. What do you mean by that?

RICH: I mean that power can become an end to itself. And you look at a character like Julia’s character, Selina Meyer, she has no fixed ideology.

She — as you’ve seen, contemptuous of her constituents. She doesn’t care about her family. She has no friends but she wants to hold on to that

power because she loves power, unfortunately.

You may disagree but I suspect that’s more often than not the case with politicians regardless of party or their beliefs ostensible convictions.

We had a moment in the pilot of eight years ago that we didn’t use that to me sort of symbolize the whole show which is that a potential hire in her

office is waiting for his appointment and he gets to a battle with a receptionist about who is going to use the outlet to plug-in whose

Blackberry.

And that was to me the ultimate Washington, even fighting over the power of where you can recharge your phone.

ISAACSON: How did “Veep” the show evolve based politics evolving during the period it was on?

RICH: Not that much until Trump. I would say that “Veep” started with a solid basis of a handful of six, seven, eight characters and that was

always the root of the show.

And Armando Iannucci who created it is among other things a Dickens scholar. He has a film version of David Copperfield that’s imminent.

And to me, his character is so sharp and there’s such — have such strong human traits, often despicable one. But you look at characters like Selina

or Jonah or Gary, Selina’s bag man. And I feel that character is the basis of it and then politics was in a way secondary.

Keep in mind, the creator was British. He was looking at it from a distance, which I think really worked. It was not inside baseball at all.

He was looking at the absurdity of it which happens to be a talent of his. He did the recent movie “The Death of Stalin” which you may have seen which

was blatantly about that kind of politician.

And so we’re aware of current events but it’s not “Saturday Night Live”. It’s not that kind of satire.

ISAACSON: One thing about your T.V. show is they seem, to me, to combine sort of politics in our current light but also Shakespearean drama. And

especially with “Succession” which reminds me not just of the Rupert Murdoch family but of King Lear’s family.

RICH: Well, I think there’s very much in there. I think it’s very much a tribute to a writer named Jesse Armstrong, a British writer who created

“Succession”, also worked briefly on “Veep” and definitely has that in his bones.

So we have a number of play writes. We have British and American [13:45:00] play writes on the writing staff. And so I think that’s there.

I don’t think the show would work without it. I think a satire of a Murdoch or something red stone or any media mogul you want only takes you

so far.

And in the end, I think it’s the — I don’t want to be pompous or pretentious about but it’s a King Lear thing of a father with his adult

children trying to please him to get power from him is what makes the show work.

ISAACSON: Let’s show a clip from that and you can help explain the underpinning.

RICH: OK.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: What have you had your entire life that I didn’t give you?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I’m not getting into it. I’m doing this thing. OK? I don’t owe you anything.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I blame myself. I spoiled you and now [bleep] and I’m sorry. I’m sorry but you’re nothing.

Maybe you should write a book or collect sports cars or something. But for the world, nah, I’m sorry. You’re not made for it.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ISAACSON: So tell me about the show. It’s entering its second season.

RICH: It is. We’re just finishing up shooting the second season which goes on in August.

But, you know, look, I’m the producer of the show but I have to say that writing is a way — that writing holds up between a father and son, even if

you don’t know what their profession is or what their business life is.

And one of the tricks of the show is we want to tell the business story but never let the business story take over because it really is about these

people.

ISAACSON: But it is very connected to the Murdoch family saga.

RICH: Right. To a certain extent but if you went in the writers’ room which is in — who puts the show together in Brixton in London, you would

see Robert Maxwell files. You would see DisneyWar by Jim Stewart. You would see of, course, Murdoch’s stuff, Murdoch material but also Sumner and

Shari Redstone. All of these is such grits for us.

ISAACSON: These are great media moguls. They’re powerful media.

RICH: Right. And often, we’re — had their families involved in the business in some way or another or had struggled but, you know. So

something like the Katzenberg struggle over Disney turns up in very different form but it’s all sort of mashed up.

You take nonfiction materials but then you fictionalize it heavily and draw what is in your heart and mind. Not just what is in the facts of

yesterday’s news.

ISAACSON: But there’s a political undercurrent to “Succession” of somebody who is manipulating our political system.

RICH: Absolutely. That is basically right wing. And there’s some of Murdoch in that but there’s no Roger. And we don’t, again, we don’t talk

about contemporary politicians.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You haven’t been yourself.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

RICH: He has a political agenda but it’s quite cynical. And, you know, he believes some of it but not necessarily all of it.

And kind of, again, this is like the Murdochs. Although we were there ahead of them having their public disputes. There’s some dissension, a

little bit of political dissension, among the siblings from their father’s political point of view.

ISAACSON: Do you think Murdoch is cynical?

RICH: Yes, I do. And I think that that’s one thing we played within the show.

In the end, it’s more about power and money than it is about necessarily conviction. We had some convictions and I’m sure Murdoch does, too.

But I think that central core is what is in it for me? What can I get?

And this is, you know, the part of Murdoch that would allow him to have a fundraiser for Hillary Clinton and Conservatives. And that makes him more

interesting.

If these characters, including Logan Roy, are fictional character, were just right-wing eye logs, I don’t think that’s very interesting drama. If

what happens around the edges of that is more ambiguous that makes people interesting.

ISAACSON: What fascinates you about Rupert Murdoch and the whole “Fox News” empire?

RICH: Well, Murdoch, you know, I think is an incredible success story. I mean it’s just amazing.

He’s been unstoppable. I’m less interested in the cable news part of it.

I mean I feel — “Fox News” is, in some ways, an overstated story. And I don’t really believe that Americans are brainwashed by “Fox News”.

[13:50:00] Because I feel the people who watch “Fox News” pretty much like I would add, the people who watch “MSNBC”, are there because they already

believe in what the slant of the network is and want their beliefs validated.

But that Murdoch was able to come to, first to England, and then here to America and create this empire with a lot of odds against him is a great

story. Whatever you think of him, it required a kind of ruthlessness, intelligence, and cleverness.

And you don’t really know what his beliefs are but he has this drive that is compelling to watch.

ISAACSON: You’ve had many careers in a way. Famously, as a theater critic at the “New York Times”, political and culture columnist at “New York

Magazine”. What do you think of the state of journalism these days and what’s caused it to become so fractured and vulcanized?

RICH: I’m not sure if I know what you mean by the vulcanization. Do you mean —

ISAACSON: We become more polarized as a society (CROSSTALK) —

RICH: I don’t think that’s —

ISAACSON: — feeds into it.

RICH: Yes, I don’t think that’s the press’s fault. I think that — “Chicago Tribune” was a very conservative paper. The “New York Mirror” was

a right-wing paper. The “Herald Tribune” was a Republican paper. “The Times” was a Liberal Democratic paper, more or less.

That whole — that hasn’t changed. The names have changed. Some of the politics have switched.

I don’t think — I think that’s always been there and I don’t think it’s caused by the press. I think that’s just the way it is. There’s always

been a partisan press in this country.

I think the vulcanization is more from our politics. And if I had to say sadly, tragically, the single biggest factor, the two single biggest

factors are race and class.

And I think it’s the bottom of all of it. Class and somewhat race, the case of this populist rebellion but, you know, look at the story of race in

this country.

It’s tragic. It’s unending. It’s going on tremendously in the Trump era.

We had a terrific, in my view, African-American president. We all thought, oh, we turned a corner. Not we all but a lot of people did including

briefly me.

And it turns out no, this original scent of this country underlines all the visions. And when you look at something like Charlottesville, that’s the

problem. It’s not the press.

You look at that melee and the forces that work there as a microcosm or a template for what is going on elsewhere in this country. And not just in

this country. It’s very upsetting, it seems intractable.

ISAACSON: In your T.V. shows, “Veep” and “Succession” and then your columns in “New York Magazine”, to what extent can you and are you trying

to push ideas that you think will nudge the country into a better place?

RICH: Well, I think anyone who writes — certainly you’re a classic example wants to do that. And that’s true also working in fiction and in

television.

Of course, you want to advance those ideas. And I certainly spent a lot of time, particularly as columnists as trying and you have to keep trying but

you have to recognize reality.

A perfect example is gun control. How many people do we know, including myself countless, you know, pieces of gun laws in this country? But it

doesn’t — it hasn’t had an effect even the actual mass murders have had marginal effects so far and actually changing the laws.

And so you have to be humble about it. You have to do it. But in the end, it’s going to have to happen in the political arena. And if I had to say,

if I had a great hope for the end of this story, not the end end but a situation, it really is with younger people.

I really do feel — I think — I know there’s a lot of people who are sort of contentious with millennials, I don’t really feel that.

I feel the young people I know, some of them by now adult but children are very committed to changing this, very committed to being part of — in the

arena. Not necessarily running for office but voting, trying to deal with issues like race, climate change, guns.

I feel it very strongly. Not in the way they’re doing it. Not in the way my generation did. They’re maybe doing it in a better way but that’s what

gives me hope about that.

ISAACSON: Frank, thank you so much.

RICH: Thank you, Walter. Appreciate it.

(END VIDEO TAPE)

AMANPOUR: And that’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching ‘Amanpour and Company’ on PBS and join us again next time.

END