Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

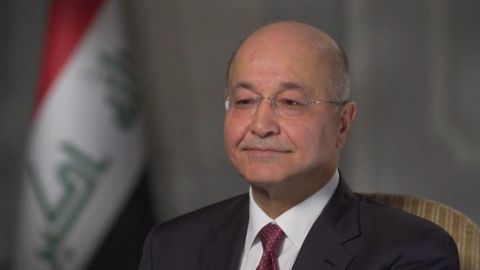

The doors to diplomacy are closed, Tehran tells Washington as tensions ratchet up. What does all this mean for Iran’s Persian Gulf neighbor,

Iraq? My interview with the president, Barham Salih.

Then, after reports of shocking conditions at detention facilities in Texas, I speak to the lawyer, Warren Binford, about what she saw inside.

Plus, unearthing the real China by offering free taxi rides in Shanghai. NPR correspondent, Frank Langfitt, talks to our Hari Sreenivasan.

Welcome to the program, everyone. The Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani, has accused the United States of suffering a mental disability after the

Trump administration issued new sanctions against top Iranian leaders, including the supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei.

In response, President Trump has tweeted that an attack by Iran on anything American will be met with overwhelming force and even obliteration. Iran’s

Persian Gulf neighbor, Iraq, is worried about being caught up in the maelstrom, where angry words and crippling sanctions could spin out of

control, even between leaders who say they don’t want war.

Mindful of America’s disastrous 2003 war in Iraq based on false intelligence, I asked the Iraqi president, Barham Salih, what all this

means for his country, for the region, and indeed, the world.

President Salih, welcome back to the program.

BARHAM SALIH, IRANIAN PRESIDENT: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: You are here at a very, very crucial time with this massive ratcheting up of tension between the United States and Iran. And, of

course you sit in the middle of that in that region. Do you feel the escalation and can it threaten Iraq itself?

SALIH: We are truly concerned with the escalation and we are concerned about the ramification for Iraq. Iraq has been going through hell over the

past four decades. Latest episode of conflict was the devastating war with ISIS. We want to focus on reconstruction, reconciliation and we want to

move on. Yet, we are being dragged into book these dynamics of conflict.

And I say to all the actors in the region as well as to the global actors that Iraq security, Iraq’s stability is important, vital and it should not

be under estimated the success we have achieved. Defeating ISIS with the support of the United States and the international coalition, with the

support of our neighbors has been monumental success. It should not be under estimated and it should be protected, not squandered.

AMANPOUR: What do you make of President Trump announcing that he stood back from ordering a strike, a retaliatory strike on Iran?

AMANPOUR: Obviously, we’re happy that war has been averted. This part of the world has been going through cycles of conflict for so many years. We

don’t need another war. And there is no military solution to this problem. There are serious problems affecting regional order in the Middle East and

this is nothing new.

We have reached a new heightened state of, I would say, tension, escalation. At the end of the day, the parties need to sit down together

and focus on what is important, really combatting violent extremism, focusing on regional integration, and economic issues, think about the

Middle East and the legions of unemployed youth who are demanding jobs, who are demanding education, who are demanding a fair share of resources of the

nations. This is not the way to go forward. That — this part of the world needs fundamental solutions, not another war.

AMANPOUR: Well, and you would be in the best place to know that given the misguided war, it turns out, that happened in Iraq in 2003.

But I want to ask you, because if military intervention has been, at least, postponed for now, the war of words is ramping up between not just the

governments but between the presidents now. President Trump saying things about Iran. And now, the latest, President Rouhani in a rather

uncharacteristic outburst, calling the White House mentally retarded for its actions and its announcement of brand-new sanctions.

How do you analyze that outburst on a televised address? Is Iran feeling the pressure?

SALIH: No doubt Iran is hurting. I mean, the sanctions are hurting and this escalation is hurting the entire region not just Iran, to be fair.

Everybody is on their nerves and this is not a happy situation for any of the actors in the region, to start with. And it’s best to

deescalate, it’s best to focus, as I said, on what is important. This is not the way to solve this problem. The way to solve the problem is

dialogue, sitting down to a table and really begin hammering out the fundamental issues that are affecting that part of the world.

AMANPOUR: Let’s say the United States has legitimate grievances with Iran. What would your advice had been had you been asked by President Trump and

his administration regarding the Iran nuclear deal and pulling out? Because it’s obviously that that has caused this massive escalation as Iran

is being squeezed by the American’s maximum pressure campaign.

SALIH: Let me remind the audience of that sanctions have been tried in many, many countries. And we in Iraq have suffered from sanctions in the

1990s and the devastation that has inflicted Iraqi society has been really enduring, even today, by the way. So, we feel for the people of Iran as

they’re being subjected to these sanctions.

And there is also a fundamental question whether this is the way to bring about the change in behavior and policy that is being sought out. The

nuclear deal was welcomed by many in the region, once welcomed by the Europeans, once welcomed by the world as a way to go beyond that impasse.

There are issues with that nuclear deal, this needs to be negotiated, it needs to be discussed and had the alternative of abrogating the deal, it

could be disastrous for the entire neighborhood as a whole.

AMANPOUR: Well, let’s talk about Iraq. Would you agree that it was the United States war in Iraq that essentially allowed Iran to expand its

influence and it expanded into your own country, as you know?

SALIH: I disagree with that, fundamentally. It was Saddam Hussein’s policies of ethnic and sectarian discrimination, Saddam Hussein’s policies

of genocide and repression that destroyed the Iraqi State and allowed all kind of foreign influences to increase inside Iraq. Iraq-Iran war was a

devastating blow. Iraq was a devastating blow to Iran. And we are still, by the way, dealing with the continues consequences of that war. Don’t

under estimate that.

Iran and Iraq neighbors. We have 1,400 kilometers of borders. People of Iran’s influence inside Iraq but there is also Iraqi influence inside Iran,

too, as well. Don’t forget the fact that Najaf is the center of Shia Islam. And Najaf’s influence in Iran is no — not to be under estimated.

These neighborhoods have lived together. There are social, cultural, economic ties that have bound the two people for centuries, for millennia.

So, this is not a mathematical equation, as some people try to look for a turning point here and the weakness of Iraq. The destruction of the State

in Iraq came with the policies of Saddam Hussein.

2003 war, many Iraqis welcomed it as a way to move towards liberty, towards a democratic system of government and deniably, the transition in Iraq has

been painful. And the Iraqi people have not attained what they have aspired to. We still have a lot of work to be done. But the problems of

Iraq predate 2003.

AMANPOUR: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently made an unannounced visit to your country. And there were fears. Apparently, he spoke to you

about the potential intelligence that suggested pro Iran Shiite militias inside Iraq would attack U.S. troops in the region.

What intelligence did you have on that and what are you telling them about attacks or any action against American interests there?

SALIH: There is a policy of the Iraqi government endorsed by the main political parties, including the commanders of the Hashd al-Sha’abi, the

People Mobilization Forces. These forces are to be commanded, are commanded by the prime minister. And the policies that these American and

coalition forces that are present in Iraq are at the behest of the Iraqi government, at the invitation of the Iraqi government, 12 Iraqi forces

fight ISIS and enabling us in the war against terror. Any attack of those will be an act against the State of Iraq and the State of Iraq, the

government of Iraq will be taking them on.

To be fair, a couple of incidents have happened recently. All the key players in Iraq, all the political leaders of Iraq, including the

commanders of the Hashd al-Sha’abi, have come out condemning those. There are — there could well be French groups who may want to

destabilize the situation. The policy of the government, the policy of the political leadership of Iraq is really not to allow that. We do not want

to be dragged into this conflict. The international coalition that is there is there at the invitation of the Iraqi government. They’re helping

the Iraqi forces fight ISIS. Consolidated the victory of (INAUDIBLE) against ISIS. And any act against it, it will be an act against the State

of Iraq in the sense of the (INAUDIBLE).

AMANPOUR: I wonder how long Iraq wants to see American troops stationed there? And I’m going play this little bit of an interview that President

Trump gave to “CBS News” recently.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DONALD TRUMP, U.S. PRESIDENT: We spent a fortune on building this incredible base, we might as well keep it. And one of the reasons I want

to keep it is because I want to be looking at a little bit at Iran because Iran is a real problem.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: That’s news. You’re keeping troops in Iraq because you want to be able to strike in Iran?

TRUMP: No. Because I want to be able to watch Iran. All I want to do is be able to watch.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: How do you feel about that?

SALIH: We — at the time, we came out clearly and in a statement by the government of Iran, the American troops, the coalition troops in Iraq out

there, again, at the invitation of the Iraqi government for the specific exclusive mission of fighting ISIS. We do not want our territory to be a

staging post for any hostile action against any of our neighbors, including Iran. And this is definitely not part of the agreement between the Iraqi

government and the United States.

AMANPOUR: How long would you like to see U.S. troops stay there?

SALIH: It depends on the requirement of the Iraqi government and the assessment of our commanders. I want to say the following, the victory

against ISIS has been quite significant, not to be under estimated. Four years ago, one-third of Iraqi territory was under the control of ISIS, but

this fight is far from over.

We are still engaged and we need to be careful not to allow ISIS or another manifestation of ISIS coming back. And therefore, the collaboration

between Iraq and the international coalition continues in order to make sure this is eradicated.

AMANPOUR: Would you say the rise of ISIS four years ago was a direct result of the withdrawal of U.S. troops at that time?

SALIH: I think it was a combination of factors. Definitely there were the lack of security arrangements and I think, at the time, when the American

forces left Iraq, perhaps not enough attention has been given to developing the security mechanisms that can keep control of the situation. But there

were other factors, political as well as intervention and interferences by actors who really wanted to destabilize the Iraqi situation.

There is a Kurdish proverb saying, “Never throw a snake into your neighbor’s home or yard.” Too many actors in this neighborhood have been

playing with this terrorism card and violence card. At the end of the day, people might have thought that Iraq would be afflicted with this, but it

turned out to be a regional and perhaps, even global threat.

Time for us the neighborhood, the world, to really focus on the real issue at hand, eradicating the threat of violent extremism and not allowing

ourselves to be sort of walking into yet another episode of conflict. We’ve had al-Qaeda, we’ve had ISIS. We do not want to deal with the sons

of ISIS.

AMANPOUR: It so happens that also in your neighborhood a little further down, the Persian Gulf in Bahrain, this week, will be the U.S. workshop on

the economic part of the administration’s peace plan for Israel and the Palestinians.

You’ve seen that the Palestinians have rejected it. They say, you know, “You can’t bribe us. You can’t buy us out. We want our freedom and our

independence.” Where do you stand as the president of Iraq on this workshop and the general policy of this administration toward Israel and

Palestine?

SALIH: The government of Iraq supports the rights of the Palestinian people to a state and we will be supporting the position of the

Palestinians. We’re not a party to this conference in Bahrain. And we will, at the end of the day, do what the Palestinian considered to be right

for the cause and we will be supporting the cause.

AMANPOUR: One of the main planks of the U.S. policy against Iran is to squeeze their oil exports. They want you, Iraq, to wean yourself away from

Iranian energy. You are currently doing it under a waiver program that the U.S. offer some of its allies. Can you wean yourself off Iranian energy?

Will you wean yourself? Is it the right policy to squeeze Iran? And for you, economically, does it make sense?

SALIH: At the end of the day, we live in this neighborhood. There are important economic interests that bind Iraq and Iran together and this is

not a zero-sum game. And the situation Iraq finds itself is not a consequence of today or the last six months of this present government that

has been in power. Iraq has been devastated by war, conflict and its economy has really been crippled.

We are working hard to energy self-reliance. There are many initiatives that the government has taken. But to expect Iraq to basically separate

itself from Iran with 1,400 kilometers of border and the important, social, religious economic interest that binds Iraq and Iran together, it just is

not practical.

And it’s not about Iraq, it’s about Turkey, it’s about the Gulf. Many of the protagonists in the Gulf have very, very deep economic relations with

Iran. Really what we have gone through over the last decade, if not the last four decades, if I were to consider the Iraq/Iran war, the sanctions

in the ’90s, war in the Gulf in 2003, the onslaught of terrorism, Iraq, four decades of conflict, you know.

Imagine a car bomb everyday over 40 years. This country needs a reprieve. If you were to counter back (ph) that today, you will see serious progress,

you will see normal (INAUDIBLE) lost time. I saw you in Baghdad, we were being swept by car bombs almost every day. It was a devastating situation.

Normalcies returning back to Iraq.

AMANPOUR: Given that you are loud and clear saying that another war in that region is going to be a disaster, do you see parallels with the U.S.

rhetoric, the build-up, the patent directed at Iran today with what was happening towards Iraq under the George w. Bush administration?

SALIH: Saddam Hussein was a unique dictator. He committed genocide. He engaged in acts of aggression across the neighborhood. He presented a

threat, a direct threat to his people, and we lived through that, my generation lived through that. Iraqis were yearning for a real change.

Again, the dynamics of inside Iran, this is a matter for the people of Iran to decide and for them to discern. But for 2003 — and Saddam Hussein, I

think, he was a unique case in history. But the parallel is as follows. It’s easy to start a war but very, very difficult to end a war.

AMANPOUR: President Barham Salih, thank you so much indeed for joining me.

SALIH: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: Really interesting lessons from the past.

And back in Washington, the U.S. government’s treatment of detained migrant children is under sharp new scrutiny, amid shocking reports of the squalid

living conditions and a lack of basics, like food and water and hygiene at many facilities.

Nearly 250 children were moved from one overcrowded station in Clint, Texas but a hundred have been taken back to the same place. One child reportedly

said they have not showered in three weeks, outraging lawmakers from both sides of the aisle. The law calls for safe and sanitary conditions. And

one government lawyer is in the spotlight for seemingly heartless and careless view.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ATSUSHI WALLACE TASHIMA, U.S. 9TH CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS: If you don’t have a toothbrush, if you don’t have a soap, if you don’t have a blanket,

it’s not safe and sanitary. Wouldn’t everybody agree to that? Do you agree with that?

SARAH FABIAN, U.S. JUSTICE DEPARTMENT ATTORNEY: Well, I think it’s — I think those are — there’s fair reason to find that those things may be

part of safe and sanitary.

TASHIMA: It’s not maybe, are a part.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And that, of course, went viral. Now, the acting customs and border protection commissioner, John Sanders, has resigned today.

Warren Binford is a lawyer who visited the Clint facility in Texas and she helped get these stories out. And she’s joining me now from Los Angeles.

Warren Binford, welcome to the program.

WARREN BINFORD, PROFESSOR OF LAW, WILLAMETTE UNIVERSITY: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: I mean, you’re a lawyer and you heard that government lawyer stumbling through a particularly easy question to ask. I mean, doesn’t

that really sum up why there are this terrible, terrible — this terrible situation going on, if they can’t agree on a definition of what is safe and

sanitary?

BINFORD: Yes, I think that’s right. And that’s why we are offering to both the congressional leaders and to the White House that we will bring

together a team, pediatric experts, to sit down with them and try and come up with a bipartisan definition of a safe and sanitary conditions for these

children so that we can ensure that this never happens again.

AMANPOUR: Now, in the wake of your visit to Clint and the lawyers, you know, your team of colleagues, there’s obviously been outrage that shocked

people all over the United States and there was, we thought, some sort of redress when, yesterday, 250 of these children were removed

from that particular facility. Then we hear a hundred of them have been moved back. Can you describe what is going on there and why that would be

the case?

BINFORD: I have no idea why that would be the case. The situation with these children is that most of them have family in the United States. If

you look at the population of children who are kept in these facilities last year, 86 percent of them had parents, family members, other sponsors

here in the United States. So, these children don’t even need to be there. There are only about 14 percent of these children that need to be in the

government’s care. And for those 14 percent of the children, we need to have standards set about what is safe and sanitary means.

For the other 86 percent of these children, they need to be returned to their families so that their families can care for them and make sure they

are fed, they are clean and that they are treated with the appropriate level of love and care that each child deserves.

AMANPOUR: Warren Binford, describe for me some of what you saw and how you even got access to these facilities?

BINFORD: Well, Christiane, we have access to these facilities through the Flores lawsuit, which was a lawsuit brought in the 1980s to make sure that

children who were in government custody were properly cared for. And so, for the last 20 years, we have had teams of experts going to these

facilities and then reporting back to the court what they are hearing from the children.

So, we have never gone to the media before because, really, these inspections are intended to inform the court. However, what happened this

time is that we walked in those facilities, which is only intended for 104 adults, and this is a border patrol facility, which are notoriously squalid

and not appropriate for children at all.

And they handed us the roster of children who were on site that day and there were over 350 children in this border patrol station. So, we were

horrified. We immediately scanned the list and we saw there were over 100 of these children who were young children, who were infants, toddlers,

preschoolers, school-aged children.

We then looked further at the list in-depth and we identified that there appeared to be about half dozen child mothers who are there trying to take

care of their infants. We immediately asked the guards to bring us the youngest children, the child mothers and their infants and the children who

had been kept there the longest. And when they walked into the room, Christiane, we were taken aback. They were dirty, hair was matted, they

started crying, they had just a level of hunger that made them, you know, want food from us directly because they hadn’t been given any fruits, any

vegetables, any milk for the entire time that they had been there.

They were given instant soup, instant oatmeal, frozen burritos. It was — and it was the same food every day, day after day. They described sleeping

on cold floors, which was is why they said they were so tired. They were sleeping on cement blocks, some were sleeping on mats that had been

provided but they were too few, the mats were too few. And so, they were describing having to sleep six children on a mat in order to protect as

many children in the cells as possible from the cold floor.

We couldn’t figure out how it was that they were keeping 350 children in this facility. And so, we talked to the chief officer and he reported that

they recently expanded the facility. But the facility expansion was nowhere to be seen. We drove around. They refused to give us a tour of

the facility. And, you know, now we know why they didn’t want us to see it.

But we went around the facility on the outside after we were done interviewing the children all day that first day, and all we could find was

a cheap flimsy warehouse with no windows that appeared to be recently erected. But we couldn’t believe that they really would be keeping

children inside a facility like that, a warehouse.

So, the next day, we asked both border patrol officers and the children where they were being kept, and a number of the children reported that they

are, in fact, being kept in that warehouse. One little boy described currently 100 children being kept in the warehouse and he said that the day

he arrived, there were 300 children in that warehouse.

We discovered an influenza outbreak which caused about 15 children to be quarantined, where no one was actually actively caring for them. We also

discovered that there was a lice outbreak in one of the cells. And according to the children, the six children who were identified to have

lice were taken and given lice shampoos but then the other children were given two lice combs and told to pass the lice combs around, which is

something you never do —

AMANPOUR: Yes.

BINFORD: — with a lice outbreak.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

BINFORD: Then what happened was, the lice comb was — one of the lice combs lost. And so, the children did report that the guards

became very angry at them and yelled at them and scared the children and made them cry and took away their bedding as punishment for losing this

comb. And we were so shocked when we heard this on Wednesday afternoon that we decided to extend our visit by one more day and we arranged to come

back on Thursday, specifically so that we could see whether or not the guards were just threatening these children to try to scare them or if they

really were going to make an entire cell full of children sleep on concrete floors.

And when we came back the next day, we spoke to several children who confirmed that, in fact, the guards did not return their bedding to them

and that the cell of children were forced to sleep on concrete floors as punishment for losing a comb that night, the night before. So, it’s just

horrific circumstances everywhere we looked.

AMANPOUR: I mean, it is actually mind boggling. And the way you’re speaking, it could be out of Charles Dickens. I mean, this is something,

you know, worse than you would see in Oliver Twist or wherever.

I want to understand how this can happen. Because I assume that if you had been, you know, a social worker going to somebody’s home and finding this

kind of conditions, you would have to report these caregivers to the local authorities, to the government. I mean, how is this — how does this

happen and what are the reasons for it?

BINFORD: So, you know, let me be generous to the government and say how I think this is happening. So, these border patrol stations have always been

notoriously dirty, unsanitary, et cetera, which is why everyone has always agreed that children don’t belong in these facilities.

Under law, they are supposed to move children out of these facilities as expeditiously as possible and in no event are they allowed to keep these

children in these facilities for 72 hours. But what we have seen over the last couple of years is a massive mismanagement of the Office of Refugee

and Resettlement’s treatment of children in its care. So, that they are currently spending approximately $775 per day per child to keep children in

ORR facilities, which is draining that agency of its funding and they’re keeping the children in those facilities for nine months or longer in many

cases.

We’ve interviewed children at those facilities and confirmed that the children are being kept there for months when they are only supposed to be

kept at the ORR facilities for a few days. So, basically, to go over it, the child comes into the United States usually with a relative, is being

separated from that relative, they are taken in by the border patrol which immediately notifies ORR that they have a child with them and they take

that child out of border patrol facilities and put them in an ORR facility where ORR tries to reunify that child with the family.

But what is happening is that ORR’s facilities are being mismanaged by both private organizations and nonprofit organizations that are making a

tremendous amount of money in caring for these children and keeping them in these facilities even though 80 percent of these children have a place to

go here in the United States, most of them with family.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

BINFORD: And then what is happening is because all the beds are being taken up at the ORR facilities through the profiting, by keeping children

there too long and mismanaging their cases, the children are being abandoned in the CBP facilities, which is making the border patrol agents

furious because they know that they are not set up for children.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

BINFORD: They know that these are not conditions for children.

AMANPOUR: Let me read what they have actually said. A spokesperson said in response to your reporting, “We completely agree with some of the

reporting that has gone out in that unaccompanied children should not be held in our custody. We do not want them in our custody. Our facilities

are not built for that.” But then they went on to dispute the descriptions of, you know, lack of basics and the shortage of basics.

But I mean, you have laid it out pretty concisely. And it turns out that lots of residents seem to have been bringing, you know, some sanitary,

whether it’s nappies or diapers rather and toothpastes and et cetera, some of which was turned away. I mean, we have, you know, a whole tweet thread.

“I heard you all need soap and toast paste for the kids. Maybe more will be on the way soon.” This is the “Texas Tribune.”

And yet, some of it was turned away. So, you have this collision of facts that the CPB is not set up for this and yet, this is happening. The money

is huge and yet, it doesn’t need to be spent because, as you say, most of these kids have relatives. I mean, why is it happening then? Is this a

political decision to keep them here? Is this somehow red meat to a base? I mean, why is this happening in your legal opinion?

BINFORD: Well, in my legal opinion, I think that this is happening because people are conflating that children’s care with immigration and really it

needs to be segregated. What needs to happen is that we need to have both the Democrats and the Republicans come together with the White House and

provide national leadership on the standards of care for children who are in the custody of the U.S. government and there needs to be agreement that

these children should not be the responsibility of the government and the American taxpayer.

We need to get these children to their families. And for those few days that they are in the government’s custody, we need to agree that the

children should be fed, that they should — the youngest children should have diapers, that there should be soap.

The World Health Organization says you can reduce infant mortality by doing nothing but practicing safe handwashing. So we really need for the White

House and the Democrats and the Republicans to come together to sit down with national pediatric experts and to carve out bipartisan legislation

that not only can help these children get the standards of care that they need and they deserve that can actually help to bring our nation together.

Because this is truly something that I think gives us an opportunity to start working across the aisle. The American public is willing to and

ready to drive down to these facilities and take these children into their homes if that’s what needs to happen in order to make sure that these

children are fed and well cared for.

But I don’t think that needs to happen. All we need to do is for people to stop politicizing these children and to meet us at the border, have us come

to Washington, D.C., and we can get legislation out this week if people would simply start politicizing — stop politicizing these children and

working across the aisle and removing this debate from the immigration debate and making it what it is which is a child welfare issue.

AMANPOUR: I want to read you a couple of comments from some of our colleagues, journalists who’ve been held in prisons around the world, some

black humor here.

David Rohde of the “New York Times” who was held by the Taliban said, “The Taliban gave me toothpaste and soap.”

Jason Rezaian who was held by the Iranian government said, “I had toothpaste and toothbrush, not exactly Aquafresh of Tom’s, from the very

first night. Actually, I had almost nothing else in my cell when I was in solitary confinement. I was allowed to shower every couple of days.”

I mean we can smile at that but when I hear what you’re describing is these children on concrete floors. Maybe an aluminum thin sheet thrown over them

for warmth.

But mostly I want to know from you who are looking after these tiny little children? I mean, there are little infants there who are separated from

their parents.

And it wasn’t the border guards and nanny patrol looking after them. Who is looking after the little children?

BINFORD: So basically, most of the infants were there with their child mothers. And as we all know, children who have babies need a high level of

support from the adults who are with them in order to care for them.

There was one infant child who developed influenza and because there was no one caring for the children who were quarantined, the child mother had to

go in there with her infant. The child mother then developed the influenza and couldn’t care for her infant. So they took the infant and gave it to

another unrelated child and had that unrelated child caring for that infant.

The toddlers that we saw, some of them were cared for by children who were as young as 7 or 8-years-old. And we talked to the older girls in their

cell and what they said is that these very young children, 7 and 8-years- old, simply don’t know how to care of the toddler. And so the —

AMANPOUR: Well, no. Of course not.

BINFORD: Yes. You know, but really what we need is for these children to be with their families, including the child mother so they get the support

that they need and get them out of government custody.

There are currently 1,000 children who are in these facilities in the United States of America. And not only do we need national leadership on

this, but frankly we need the international community to start to put pressure on the U.S. government to address this crisis.

AMANPOUR: Wow. I mean that —

BINFORD: That’s an immigration crisis.

AMANPOUR: That’s a remarkable call. That is a remarkable call. Warren Binford, thank you so much for your eyewitness testimony on this truly

horrendous issue. And we’ll learn more from you as this continues.

We want to move now though from borders and detention to a story about breaking down cultural barriers. When Frank Langfitt moved to China as an

American journalist for National Public Radio, his job was to get people talking.

Yet as a foreigner in a new country, locals were wary. Instead of giving up, Langfitt tried a different approach. He created a free taxi service

offering rides in exchange for conversations.

His new book, “The Shanghai Free Taxi” chronicles his journeys while providing a unique insight into the many facets of contemporary Chinese

culture. He sat down with our Hari Sreenivasan to discuss what he learned along the way.

Now, some photos in the interview have been omitted or blurred to protect the privacy of the people Frank met while working on his book in China.

HARI SREENIVASAN, CONTRIBUTOR: A free taxi. Explain this idea, how you came up with it.

FRANK LANGFITT, AUTHOR, “THE SHANGHAI FREE TAXI”: Sure. So in 2011 — I had worked in China going back to, I guess about 1997. And so I had a feel

for the country but I had been away for about 10 years as a reporter and I returned in 2011.

And I could see that the country changed dramatically. Certainly, economically. But you could also see that there were big problems with the

corruption and the Communist Party was losing the hearts and minds of the people very rapidly.

And I wanted to try to figure out where the country was going but do it in a different sort of way. So a foreign reporter, particularly American

reporter, asking political questions of ordinary Chinese is kind of a non- starter.

I had been a taxi cab driver years and years ago. And I found that was a great way to get to know Philadelphia, my hometown.

So I decided I would set up a free taxi with no idea whether anyone would actually get in it. And I drove out and tried and so it happened.

SREENIVASAN: So this isn’t like one of those Cash Cab?

LANGFITT: No, no.

SREENIVASAN: The cameras are not rolling when you get in?

LANGFITT: No.

SREENIVASAN: It’s a normal taxi?

LANGFITT: Well, what it is, is I didn’t know actually how to do this. So I first went to a taxi company and said I would like to be a taxi driver

and they just laughed.

And they said foreigners are not taxi drivers here. This isn’t going to work.

So my wife came up with the idea, Julie, to get magnetic signs and put them on a rental car and my news assistant that I was working within Shanghai,

he came up with a great slogan which was (INAUDIBLE) in Chinese which means make Shanghai friends, chat about Shanghai life.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(FOREIGN LANGUAGE)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

LANGFITT: And it was called (FOREIGN LANGUAGE) which loosely translated is free loving heart taxi. It sounds much better in Mandarin than it does in

English.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

LANGFITT: But the message got through, I think.

SREENIVASAN: Clearly, you speak Chinese.

LANGFITT: I do.

SREENIVASAN: That’s not a hurdle. Driving in China?

LANGFITT: Challenging. I’m glad I don’t do it anymore.

It’s a game of inches. It’s sort of a metaphor for competition in, you know, a country of 1.4 billion people.

So Shanghai, 26 million people. More and more cars every day. And to get to drive the city, you have to be very very careful because back when I was

driving, there weren’t many rules. And so you just kind of inch through traffic and you have to always be concentrating.

At the same time, chatting with a passenger and trying to figure out could this be an interesting character in a radio story.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. So now people are getting into this taxi. Here is a tall white guy who is offering them a free ride to wherever.

LANGFITT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: So how does this turn into relationships that lead to wonderful stories?

LANGFITT: Actually, being a foreigner, in this case, was an advantage.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

LANGFITT: There’s a lot of distrust in Chinese society. A lot of Chinese, there’s a lot of scams that go on in places like Shanghai and Beijing and a

lot of Chinese don’t trust each other.

A foreigner would actually be seen as more honest.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

LANGFITT: And so I think have I been doing it as a Chinese person, I might not have gotten many takers. And I remember actually one time where I met

these two factory workers, girls from the countryside who were coming into Shanghai and had wanted me to take them to a tourist destination.

But they — literally, there was this approach of avoidance. Like they were afraid to get in the cab.

And there was a ferry worker, I was hanging out a ferry stop in Shanghai, and he said, “Oh, don’t worry, he’s fine. He’s a foreign friend. You can

trust him.” And he said, “I wouldn’t have said that necessarily if you were Chinese.”

SREENIVASAN: Some of these trips that you take are pretty long.

LANGFITT: They are very long.

SREENIVASAN: I mean you took one out to the countryside. It’s like an amazing road trip.

LANGFITT: It was a wonderful road trip.

SREENIVASAN: And you’re the first person to take the wedding photo — I shouldn’t say the wedding photo but really of a new couple, married couple.

LANGFITT: It was. I mean I think that what we did with this case is after about a year of driving people around Shanghai, realized we really wanted

to get out of the city, see more of the countryside, and kind of get a feel for how the country had transformed from a rural country to an urban one.

And so I put an advertisement out on Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter and got — I offered to take people back home for Chinese New Year,

which is the largest annual mass migration in the world, of course.

And so it was a 500-mile drive. And when we started off, Hari, it was not easy to talk to people. I had my news assistant with a shotgun microphone

and they didn’t really warm up.

But you know how a drive is. It’s like in any culture.

And once you get 100, 150 miles on, everybody just sort of forgot the microphone and just starts talking. And then you’re almost like old

friends.

And it was really fun to actually go to the wedding office to get the license with them and take the first photograph. And so I ended up

becoming the wedding chauffeur in two weddings.

And I also became the wedding photographer because I had a really good camera. And so at the end, I gave the families, you know, all the photos

that I had.

SREENIVASAN: And these people are becoming friends over time. You’re following them not just on that taxi ride.

LANGFITT: No. And I don’t think anybody — I wouldn’t have wanted to write a book that was a thousand taxi rides in Shanghai.

What I did is I was kind of, I guess you could say a little bit auditioning people, trying to find who were interesting folks who also were wide

variety of people because I think China is increasingly more diverse in terms of points of view.

So I met up a pajama salesman, a barber. I had a psychologist who I drove to see clients and then these two lawyers who had grown up — they’re

brothers who grew up in the countryside who then moved to Shanghai, became lawyers, which is extraordinary. We’ve got two or three generations in

most countries.

And when I was last seeing them, they were working in the tallest building in all of China.

SREENIVASAN: Wow.

LANGFITT: And what was nice is I followed them for four or five years, their lives.

SREENIVASAN: Which in many ways is like, in every other country, would be 15 or 20 years.

LANGFITT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: Because they’re going through so many jobs, careers.

LANGFITT: So many changes. I mean people are changing jobs.

So when I — the two men that I drove back and I drove in their weddings, they now have three kids.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

LANGFITT: And so, you know, it was great to get to know them and also see how they were kind of grappling. Because the politics of the country

changed, also, in ways that none of us anticipated when I started the project in 2014.

SREENIVASAN: So what did you notice changing even between the time that you had reported in China before and also the changes that were happening

in front of you between 2014 and when you finished the project?

LANGFITT: Well, if you go back to 1997, most Chinese didn’t even have their own private homes. Most people that I knew worked in — had

government apartments.

And people didn’t have much wealth and Beijing was still probably more bicycles than cars. And the last time I was in Beijing, I hardly saw a

bicycle.

And what was really interesting is I had done this trip back to the countryside in 1998. Back then, I was working with uneducated migrant

workers, blue collar, who couldn’t read very well and didn’t have many prospects.

When I drove these folks back in 2015, they were white-collar people. And it was — what it came across is how in just 15 or 16 years, you’d seen a

whole new professional class grow up in China with lots of opportunities.

Passports, they traveled overseas, they owned their own apartments. It’s an extraordinary economic transformation.

And overall, when you think of human development, a very positive story.

SREENIVASAN: You’re essentially witnessing one of the largest movements socially in sheer numbers of a group of people.

LANGFITT: Ever. I mean it’s astonishing. And I would say this about the characters.

I think this is really important for people to remember when we think about the internal politics of China and the Communist Party is that rising tide

did lift most — almost all boats. Every character that I talked to, regardless of where they were on the socioeconomic ladder, they’re much

better off than their parents were.

So some of them even — people say this, living the American dream in China.

SREENIVASAN: And that translates politically how? Because it used to be that question in America, are you better off now than you were four years

ago and a year ago?

LANGFITT: Yes. Where I think it translates politically is that there’s a lot of residual support for this authoritarian regime. Because if you

think about it, Hari, if you’re 30 years old, the lowest growth you’ve ever known, average GDP growth in a year is six percent.

SREENIVASAN: It’s stunning.

LANGFITT: It’s completely stunning. There’s never been a generation like this and I assume in human history. And so you can understand.

I mean think about parties in this country, where I am in London, where I work now. If you had a political party that had delivered that kind of

growth or at least overseen that kind of growth, it would be awfully hard to beat at the ballot box, even despite all the other problems.

SREENIVASAN: Is there a distinction there between country and party?

LANGFITT: That’s a great question. There is but the Communist Party would prefer that there not be and they’re very good at this.

They try to — there’s even an anthem from the Civil War period in which they — or I guess the Revolutionary War where it’s without the Communist

Party, there would be no new China.

And what the party tries to do is make Chinese people, including some of my characters, think that to criticize the party is to criticize the country

and not to differentiate. And I even have some characters that I talk to at great length who say, you know, there was a moment when I realized that

they are different and that the party was trying to get me to think that they were both the same and that therefore I couldn’t be critical.

SREENIVASAN: And one of the other consequences of having such a dominant single party, as you point out, so many of your characters in

their lives today are benefitting from graft or conscious of graft. They just consider corruption part of the way of living through China.

LANGFITT: It has been that way for a long time and I think people were really sick of it. This was one of the things that really struck me when I

did return in 2014 is government officials were stealing with both hands.

We’re talking about trillions and trillions of dollars. I mean it’s sort of a pathological level of graft.

And what Xi Jinping did when he got in which was extremely shrewd and absolutely necessary because I do feel the party was losing control. He

did the biggest corruption crackdown in the history of the Communist Party, more than a billion people have gone to jail.

Now, a lot of those were Xi Jinping’s rivals. So it was extremely convenient and strategic but it’s extraordinary how much popular goodwill

he generated by doing that.

And you would talk to ordinary people, even liberals, people who are critical of Xi Jinping politically who would say “Thank God, he’s doing

something.”

SREENIVASAN: You mentioned that the Chinese government was at a point of losing hearts and minds. What does that mean?

LANGFITT: What that means is that people — the Chinese government isn’t really about much more than economic growth and power. And if you go back

to the Mao era, there was ideology.

But in order to save themselves, the Communist Party had to embrace market capitalism. Now, it’s more state capitalism.

But the question is if you’re unelected and the reason you’re able to claim power is you won a civil war a long time ago and you’ve had a lot of growth

but you never stood for election, you have to find some other way to hold people together.

Corruption was really eroding that. And now, what we’re seeing from Xi Jinping is really a strong national sentiment.

And what was very interesting in talking to some of the characters who in many ways were pretty liberal, fond and admiring of American principles of

democracy and the constitution, checks and balances. They also, though, saw the United States as a bully.

When they looked in the South China Sea, they felt the South China Sea really was China’s, that President Xi was right to build those islands and

to try to push out the U.S. Navy. So they saw the U.S. as real bullies. They felt like they were surrounded.

And I guess this gets at the nuance of Chinese today is they can see things from many angles. They read a great deal. They often — in most cases,

they know more about America than Americans would know about China.

And so even people who might be politically liberal still would be very supportive of President Xi because of the corruption, anti-corruption

campaign but also because of this assertiveness abroad. It makes them feel better about China.

SREENIVASAN: So how does a person in China walking down the street perceive maybe this trade war? If you keep in touch with any of your

contacts.

LANGFITT: I do.

SREENIVASAN: What do they think is going to happen? Do they think this is good? Or do they wrap themselves in flag of China?

LANGFITT: It’s the great thing about meeting all these different people is more and more now like the U.S., you get a wide variety of views. I think

some people understand that the trade war is actually in some ways good for China. Interestingly enough.

The argument being that President Trump is putting pressure on Xi Jinping and there’s more opportunities to maybe actually develop the economy

better, make it more competitive. So it would be good for Chinese people but not good for the party.

So the party controls all these state-owned enterprises. I mean it’s not like — remember that old expression? What’s good for General Motors is

good for America.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

LANGFITT: Well, in this case, economic reform is not good for the party in certain ways. The party wants to keep control of them, a lot of state-

owned enterprises for which it has a lot of power.

It doesn’t want to privatize the whole system. That would actually create greater GDP, greater job growth and things like that but that’s not in the

party’s interest.

So there are some people not a majority at all who see Trump as something of a reformer. They may not like President Trump in any other way.

Others, though, feel that he has — President Trump has overstepped his bounds by going after Huawei. Huawei is a terrific telecom company.

When I was the Nairobi Bureau Chief of NPR, there was not very good Internet in Nairobi and I used Huawei USBs to run my bureau for a year. So

I’m a fan of Huawei in that respect.

And I think a lot of Chinese, particularly down in Shenzhen where Huawei and other big telecom companies, big tech companies are located feels that

there’s sort of an unfair targeting of a company that is kind of a global leader from China.

SREENIVASAN: One of the characters that was interesting was that they had come to the United States and come back to China and they are kind of

struggling with the sort of cultural question of where they are today versus where they grew up.

LANGFITT: Yes. This was a really interesting person that I got to know — he’s an investment banker. Her parents are in the Communist Party.

They’re Communist Party officials.

The corruption, the oppression she decided she wanted to leave China and start anew. And she got an MBA in the United States so she speaks very

very good English.

She got to the United States and five months later, President Trump won the election. And she had been a great believer in democracy.

And this began, she doesn’t like President Trump. She didn’t feel like a lot of voters had paid strict attention to what was going on and she began

to become much more disillusioned about whether American democracy worked.

And she started to see the Communist Party in a more positive way because she saw the efficiency, the economic growth, the ability to change things

quickly without the messiness of democracy. And when she — it was interesting because I know when she went to America, she didn’t intend to

return to China. And in the end, she moved back.

SREENIVASAN: OK. So now here she is back in China. Talk about the messiness of democracy.

You’ve got protests in Hong Kong that have been happening every weekend over a specific issue but they’re gathering momentum. How does she think

about that right at her doorstep so to speak?

LANGFITT: Well, she actually works in Hong Kong and she lives in Shenzhen, just across the border. She says if she were a Hong Kong person, she would

be out there every night as well because she thinks that — from the perspective of a Hong Kong person, this is like a last stand against

oppression coming and the creeping of authoritarianism from the Mainland.

But I asked her about people in her offices. I was just talking to her this morning and she said a lot of Mainlanders that she works with don’t

really have any sympathy for Hong Kong people.

So it’s really interesting. Here, you have these democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong and many Mainlanders don’t really — they don’t care for Hong

Kong people.

There’s a real division between them. It goes back historically Mainlanders would go to Hong Kong in droves and buy up lots of products and

bring them back to Mainland China because the products in Hong Kong were safe.

There’s a huge problem with food safety and medical product safety in the Mainland and they drove up housing prices. So there’s a real kind of

bitter division between Mainlanders and people in Hong Kong.

SREENIVASAN: When you talk about authoritarian sort of increases that China has made, one of the things that we at least see in the press is an

increased surveillance state.

LANGFITT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: That there are a lot of people say it’s harder to get someone to talk now in China than it was five years ago.

LANGFITT: I think it is much more difficult for my colleagues now and my conversations with them doing what I was — what was much easier to do four

or five years ago. Yes, I think it’s become the job is maybe more difficult now than since the Tiananmen crackdown.

SREENIVASAN: Why?

LANGFITT: I think the government realizes that it has a very sophisticated population, that has growing expectations that is well traveled. And it

fears that if it allows people to be openly critical and to talk more that they’re basically it’s just going to erode their power.

And I will say this when I came back in 2014, I started looking at Weibo, that is the Chinese equivalent of Twitter. And I was shocked at how open

it was.

I mean there were all kinds of criticism of the government and I sort of thought what kind of authoritarian state is this? Because if this goes on

a lot longer, it clearly was going to erode the power of the government.

So I think what they’ve done, what Xi Jinping has done is doubled down on oppression.

SREENIVASAN: Given that you have this cab out in public with these magnetic signs and you’re this white guy that’s driving this cab and

there’s enough cameras around, there’s enough police around.

LANGFITT: Sure.

SREENIVASAN: Do the authorities know what you were doing? Were they concerned in any way?

LANGFITT: They definitely did because they can read the signs and I must have passed a ton of cops in Shanghai alone. I was never pulled over.

And I thought I might be. Of course, I didn’t charge so I could never be – – I wasn’t breaking the law.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

LANGFITT: What I learned later, though, is that the Chinese Ministry of State Security obviously monitors foreign reporters. They sometimes read

our stories. They sometimes interview people that we’ve talked to.

I found out secondhand that one of the spies watching me had actually been listening to the stories. And he said I would like these stories. These

are really good.

He said I relate to some of these characters. I know some people just like this.

So I don’t know for sure but it may be one reason that they didn’t bust me is because they thought the stories were pretty good.

SREENIVASAN: Frank Langfitt, the book is called “Shanghai Free Taxi.” Thanks so much for joining us.

LANGFITT: Thanks for having me, Hari.

AMANPOUR: An unexpected vote of confidence, a rare glimpse there inside China’s secretive state.

Join us tomorrow for my interview with Istanbul’s new mayor. The opposition politician whose remarkable victory against the Turkish

president, Erdogan’s party, sent people celebrating into the streets and revived hope for democracy.

That’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow.

END