Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Richard Florida is a leading urbanist. He’s a professor and also an author. And he says America’s biggest divide is not red versus blue but rather city versus suburbia; arguing that where we call home is one of the most crucial factors effecting where we sit in the social ecosystem.

He joined our Walter Isaacson to map out the state of urban hubs today from income inequality to big tech.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: You’re a great urban study scholar and you helped invent the notion of the creative class and how that was going to revitalize American cities. Explain what that original notion was.

RICHARD FLORIDA, AUTHOR, “THE RISE OF THE CREATIVE CLASS”: So here’s — here’s where it comes from; I — I was born in Newark in the late 1950s. I watched Newark decline and decay. I saw the city jobs and industry move to the suburbs.

I actually witnessed the national guards and tanks in the street. When I was a young scholar no one believed that cities could come back. So fast forward. Now it’s the late 1980s and 1990s. I’m living in Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh was hit hard by deindustrialization.

What could begin to revive cities — what I began to see was in places like New York, in San Francisco at the time, in Boston there was this group of people; scientist, technologist, start up people, artist, musicians, professor types who were coming back to cities and I couldn’t explain it.

That’s where the idea of the creative class comes from.

And when we put the numbers to it, about the year 2000, what we found is that this group of people, which was less than 10 percent of the work force when I was a boy, grew with third of the workforce and in big cities these scientist, techies, business managers, knowledge workers, and artist were now 33, 40, 45 percent of the workforce.

So that is the creative class and it is the force, like it or not for good and bad that has revitalized many of our cities.

ISAACSON: And because they moved into the urban core more than they would go to the suburbs.

FLORIDA: Yes. And I think what happened really is that — you know I wrote this book in 2002, so it’s a quite a ways — a time ago. And after about 2000, this urban rival just goes on steroids.

And — and these folks begin to cluster in cities not just because they like cities, not because they just had great parks and amenities and universities and coffee shops, what the economist have found is the cities — they’re clustering in cities (inaudible) drives economic growth, creates innovation and productivity but they don’t cluster in all cities.

Now they have gone into many cities but they tend to cluster in these superstar cities like New York or Los Angeles or London in the U.K. or these big tech ups like San Francisco or Seattle or Boston or maybe Washington D.C.

ISAACSON: You got some push back from people like Joel Kotkin who said OK, it’s a great theory but the numbers don’t show it. The data’s not there, people actually are moving to suburbs, not cities. What would your answer to that be?

FLORIDA: And it’s funny because Joel has become, believe it or not, a great personal friend and we have had some of the most vicious fights but I told him, I literally said Joel, I’ve learned about as much from you as I’ve learned from anyone else.

Look, the creative class can thrive in suburbs. And — and — and we did the data later. We started with metros, right, the suburban urban glomerations. When you look at the data there are some suburbs — you know even in — in the outskirts of Detroit; suburbs like Royal Oak and Birmingham that have very high clusters of the creative class.

I don’t think it’s an either/or, it’s a both. But here’s the point, it’s not everywhere. It’s in certain suburbs, it’s in certain cities, it’s in certain big cities, it’s in certain small cities and it’s where those places have the attributes that can engage this clustering.

ISAACSON: You began to see after “The Rise of the Creative Class” came out. Some of the downside of this sorting in America, so what did you do?

FLORIDA: So me and a guy named Bill Bishop actually worked together. He wrote this fantastic book called “The Big Sort.” So we were in .

ISAACSON: And explain what this is because it’s about (inaudible) .

(CROSSTALK)

FLORIDA: For folks watching, is the idea that in America, this is way before Trump, that we were becoming more divided, not only red and blue, we were sorting into specific kinds of communities that engaged us economically but reflected our political and cultural biased. And that those divisions — now we were talking about this is 2002.

We’re expanding overtime and I think neither one of us — certainly I could never have anticipated how big this would go. So what happened was — when you mentioned, I took some great criticism, as you do.

When you write a popular book people read it and they criticize it. I learned form that but the world changed. The world that I was envisioning of a optimistic, rosy eyed revitalization, coming back to the city in an open-minded environment became very one sided.

And parts of cities, not all cities, became, like, gentrified colonies, and our cities began to split apart. You know, this happened on steroids, beginning in 2000, accelerating after 2010.

The reason I came to this is, I was living in Toronto where I still spend a good part of my time, and this crazy crack mayor, Rob Ford, got elected, and I was thinking “In Toronto? Toronto the good? Toronto, the place that has healthcare for all, that has invested in transit, at least up to that point, that had safe streets and no gun — very little gun crime? Why would they elect this populist This is a test 08:25:06 Real time before Trump?

Because the creative crass, my creative class, was colonizing the inner city, taking advantage of the great locations close to the university, close to downtown, making money off their housing as it went up, and working people and the people who worked in those low-end service industries were being pushed out, and our community, just like our country, just like America, was becoming more divided. That’s what I began to see as contradiction of the creative class.

ISAACSON: And it led to a greater inequality of wealth that became part of the resentment, right?

FLORIDA: You know — and we actually documented this in 2002 and 2003 for essays I wrote, for, at that time, the “Washington Monthly.” You see in these creative cores, in San Francisco and Austin and Seattle and Boston and New York, inequality was the greatest in the nation. But when I came to write about this sequel book, “The New Urban Crisis,” what I found was this contradiction — the more diverse, the more dense, the more innovative, the more open minded, the more liberal and progressive, more votes for Obama, more votes for Clinton, whatever, the more inequality and more segregation.

And that contradiction was what I wanted to focus on.

ISAACSON: Why does that happen?

FLORIDA: Because of the big sort. Because of this sorting of us by economic status, by class position, by level of education, we are becoming a very sorted country in which the advantage folks cluster. It can be urban. And there are still many, many advantaged folks in the suburbs of New York, in the suburbs of California, in the suburbs around Boston.

We can sort into urban centers and suburbs, but the places we sort into become so darn expensive. You know, look at housing prices in New York or San Francisco or Los Angeles, that less advantaged people, lower skilled people, working people are pushed out.

ISAACSON: So tell me about the book, then, that you wrote, that tried to explain that problem.

FLORIDA: Well, you know —

ISAACSON: Was that a walking back of your earlier book?

FLORIDA: I don’t — I don’t think it’s so much of a walking back as recognizing that things have changed, recognizing some mistakes that I made, and really trying to interpret the world as it evolved. And here’s what it was; it kind of tracks the arc of my life. A kid born into the old urban crisis in Newark and New York City, you know, Ford (ph) declaring the city drop dead, you’re in bankruptcy, go away and crisis failure, a crisis of complete and total urban failure.

A company is moving out; people moving out. A whole — they called it, in urban studies, a hole in the doughnut. Then to see this revitalization come, slowly at first, and then flood gates open after 2000, but the new urban crisis isn’t a crisis failure. Ironically enough, it’s a crisis of urban success — it’s a crisis of urban success. The more these cities attracted talent, the more they attracted the creative class, the more they gentrified, the more uncool they became with other parts of the country and within themselves.

So — and what I argued in the book is the new urban crisis isn’t just a crisis of cities. When you see it play out on the electoral map in this divisions of this country, which you know so much about, it’s kind of our crisis of our moment of Democratic capitalism. IT really is, how do we put these two parts of our economy, the creative centers and rest of the country, back together? Can we?

ISAACSON: So what should we do about gentrification?

FLORIDA: Well, I think — you know, look, there’s a couple of things that people or policymakers and academics and thinkers are talking about. First, there is no doubt we need to build more housing where we need it — not out in the far-flung exurbs. We need to build more housing in the core and in those old suburbs, you know, which have the single family homes that can be densified. To do that, we’ve got to liberalize our use prescriptions (ph).

Number one, some people, so-called “market urbanists,” who I admire a lot, think that’s sufficient. I think it’s necessary, but insufficient. I think we’ve got to commit to building affordable housing. In New York now, we have a program, in this city, where if you’re going to build a new tower —

I forget the exact fraction, but it’s between 20 and 30 percent of those units you can’t buy out.

In that new tower, that new luxury tower, have to be devoted to affordable housing. We have to build more transit to connect people out in the suburban areas, and especially those close in suburbs, and densify around the hubs. And I think the last thing we need to do, which few people are talking about, Walter, about a third of now of us in America have the great, good fortune to be members of the creative class.

We make a pretty good amount of money, even the artists and cultural works, never mind the scientists and techies. More than half of Americans work in low wage, crappy, precarious service jobs.

Condemned to a life almost of disadvantage, almost poverty. When we decided to build the middle class in this country, we made manufacturing work good work. My used to tell me, he worked in a factory. He started that job in the depression. When he came back from World War II, FDR, the new deal (ph), his job became a good, family-supporting job. He could buy a house in the suburbs.

He put my brother and I through college. Service works can’t do that today. They are working at — you know, if Karl Marx was back to life, he would say, they’re working in immiserated, sustenance conditions. We need a national effort to upgrade the 50 percent of low wage service jobs and food service preparation, retail work, office work, that are the backbone of our economy, but people are sinking further and further into poverty.

ISSACSON: Do you think, in some ways, capitalism is broken when it comes to a market economy in cities like that?

FLORIDA: Well, in my field — my field, we have a long tradition of Marxist, post-Marxist analyst, and a lot of critics come from that part.

They want to envision — and I learn from these people, particularly a guy named David Harvey (ph), who’s absolutely brilliant. But there’s a hope for a kind of socialist utopia that doesn’t come.

So pragmatically, yes, capitalism is broken. What do I believe? I think we have to go about fixing it. How do I think we can best fix it? If we could just empower our cities to begin to address these problems, and why I think it works is because cities are in gated suburbs. No matter how gentrified

New York or San Francisco become, there are still poor people. There are still ethic and racial minorities. They are still progressive political actors who act on politics.

So I do think our cities are going to be the place, they’re going to laboratory of Democracy, that figure out the way to create a new social compact that can make this kind of capitalism work. I shutter to think at what the alternative might be.

ISAACSON: But if we empower cities, would that leave some people, like the people who live in suburbs or exurbs or in the countryside, leave them out?

FLORIDA: I think it might leave people in the reddest parts of the country out. But here’s the way I figure it, and I’ve talked to the leading theorists this — about this, both on the left and the right. Look, we don’t agree on many things in this country. We don’t agree on gun rights.

We don’t agree on women’s rights. We don’t agree on gay rights. I could go down the litany. And already, state preemption is taking a lot of those rights away. \

ISAACSON: Well, explain what that is.

FLORIDA: Well, states, you know, across this country are saying, because they’re run by rural and suburban majorities, we are going to prohibit you from acting to control guns. Bill Peduto, the mayor of Pittsburgh, who’s is a good friend of mind, has several pending civil suits and maybe a criminals case, from the Pennsylvania state government, that says he’s acting too quickly on gun control. Gay rights are another one.

ISAACSON: And minimum wage.

FLORIDA: Minimum wage is another one. Although, we see more red states, interestingly enough, at least be able to raise their minimum wage somewhat. So I think this is happening. What the best theorist of the so- called “federalism” — you know, the United States is a federal system where we can adjust the relationship between the federal, the state and local governments say.

Yes, Walter, that’s a risk in the short run. Yes, that’s Richard, that’s a risk in the short run. Over time, though, these states and cities have to compete. So what’s happening in Georgia now under the threat of these new women’s rights bans and gay rights bans, the Hollywood companies are saying, we’re going to have to pull the films that are being made in Atlanta.

We’re going to have to bring them back to a city that doesn’t impose that. So the theorists say, this competition for economic growth, well (ph), the same thing I see when I go to Texas. The business people are saying to the governor, stop it. We can’t attract an Amazon HQ two if you keep up this kind of red state looneyness, in terms of social policy.

So the theorists believe that this competition between jurisdictions may lead to some places running to the bottom in the short-term, but over time, the competition will lead to better outcomes.

ISAACSON: When you look at the big (inaudible) that you and Bill Bishop have talked about, one of them is these cities and they become (ph) enclaves of creative people, and then the areas just around them. You can look at Austin, Texas, going 90 Democrat, and same with Houston, but there’s — right around it, go 90 percent for Trump. Are we dividing our country based on the new urban elite versus the rest of America?

FLORIDA: Yes. And these divides are fractal. A big word, big word, fractal. They occur at every scale. They occur between the coastal elite places like the New York, Boston, Washington Card (ph) and the Southern and Northern California, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle.

But then even within those places, those divides replicate. I mentioned Toronto earlier. Toronto’s a very progressive place. It’s a very blue place, but even within it, there’s red and blue, liberal and conservative. And the way I like to think about it is, the knowledge economy or creative economy is very spiky. You know, Tom Friedman had a wonderful book that said the world is flat. For many things, manufacturing, simple service, the world has flattened completely.

But within that flat world that Tom explained so brilliantly, there are these spikes, and what happens is these spikes take on a different character, a different economic character, a different political character and a different cultural character. And the backlash is not so much about the economic inequity, it’s about the cultural norms and values.

If you live in an urban center you tend to not want to have guns around you. You want safety. You want to be open-minded to all those people who are contributing to your economy. You want to be pro-immigration and pro- women’s rights because women make up, believe it or not, more than half the creative class is made up of women.

Just like more than half economy — population is made up of women. But the creative class has much greater numbers of women than say the working – – the physical working class. But if you live in one of the places in the outlying areas and you’re a white middle aged man, you feel threatened.

You feel threatened by diversity, you feel threatened by women, you feel threatened by the fact that women and immigrants have gotten, in your view, a leg up. You feel threatened by the sexual and gender revolution and it creates that backlash.

So I think that backlash is not just between parts of the country. Yes, it’s between parts of the country but it’s within parts of the country as well.

ISAACSON: So in other words between counties and parishes (ph) or something where you have people who are very comfortable with diversity, very comfortable as a creative and knowledge economy and people who may feel that they’re being looked down upon or — by the elites.

FLORIDA: And so we have a divide in this country but it’s not the old — people get mistaken, it’s not the old North/South divide, it’s not a frost belt/sun belt, it’s not an east/west, it’s a new kind of divide that’s very spiky — big word — very fractal, very concentrated but I — but I think we’re about even split.

You know there’s about half of us that are populating one and that takes the creative class and some of the new immigrant groups. And about half the country that’s populating another and sometimes we live quite closely.

Here’s an interesting fact though. There’s a brand new study out that — that I found so amazing and — and hardened me for a moment you know in times of others views may think are dark.

This was a group of political scientist who know a ton about the big sort that we’ve been talking about and who studied the sorting of Americans. And not just Americans, they’ve looked at the most sorted of us, highly active liberals and highly active conservatives.

On national issues, which we’ve talked about; gun control, social issues, women’s rights, abortion; we are worlds apart. When they poll those same people on local issues; do you want your economy to grow, do you want good schools and they went down — I’m giving you big — almost complete consensus.

And that gave me hope that when we’re closer together and focused on our local communities and get out of this chamber — this echo chamber of national issues — when we’re focused on hometown — you know Mike Bloomberg used to famously say you couldn’t tell if a mayor is — what was it, there’s no liberal or conservative, republican, or democratic way to pave the street or to deal with .

ISAACSON: Pot holes have no party.

FLORIDA: Yes. Pot — thank you. Pot holes have no party. And I think that really is the case. You know I — when I meet with mayors and I work with a lot of them, it’s very hard for me to tell and it’s very hard for me to tell who’s a republican or a democrat.

So I think that hardens me. When we look at the local issues and get out the echo chamber of national issues, these — these — these high potency national issues, I think we’re a lot better to solve our problems.

ISAACSON: And so what policies would you do to try to knit the fabric closer together?

FLORIDA: So I don’t think we can. I think we’re really divided. And I think divides gotten worse over my life. You know and I’m 60 ish years old. I think we’re going to have to realize that we are best served by living together as two Americas.

And the way to reduce — I think Trump proves how problematic the imperial presidency — we — we knew it — people like you and I knew it but until you had someone who really wasn’t up for the job, you couldn’t see it.

Now you can see how problematic that institution — so what we do is take our federalist gift, this distribution of powers that we’ve dialed up.

Right. Over the past 50 years since the (inaudible) we have dialed up the power of the federal government and we begin to dial it down.

No, we don’t give all power back to the communities — and I don’t mean just the cities. We give power back to the suburbs and rural areas. We give them their tax power back, we give them their economic power back, we enable them to build their own and we enable them to create the kind of cultural context.

You know look, here’s a statistic. About 20 so percent of us live in urban areas. I forget what it is. 60 ish, 70 percent of us live in suburban areas and the rest live in rural areas. The over whelming preponderant (ph) like where we live. We vote with our feet. America we vote — that’s what the big sort is. We vote with our feet to be in the kind of places that reflect the cultural and social political context we want to live in. So let’s not avoid that. Let’s not spend every four or eight years screaming and yelling at one another.

Let’s admit that we are two or more countries and let’s live together peacefully. Let’s create a united — (inaudible) a united cities of America — I’m trying — united communities of America, united places of America it won’t be perfect but it will be a lot more robust and resilient because we’re much more successful when we distribute in any kind of system than when we concentrate it.

And I think if we reduce the stakes (ph) around these national issues, we’ve have a somewhat better chance of being able to get along.

ISAACSON: Richard Florida, thank you so very much.

FLORIDA: Thank you for having me, Walter.

ISAACSON: Appreciate it.

FLORIDA: It’s great to spend time with you.

About This Episode EXPAND

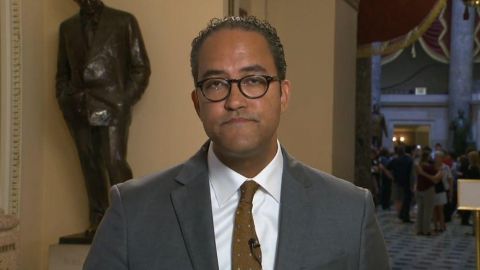

Will Hurd sits down with Christiane Amanpour to discuss what many believe to be President Trump’s most racist rhetoric yet. Isha Sesay joins the program to discuss the 2014 kidnapping of hundreds of Nigerian schoolgirls by terrorist organization Boko Haram. Richard Florida tells Walter Isaacson why America’s biggest divide is not red versus blue, but rather city verses suburbia.

LEARN MORE