Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

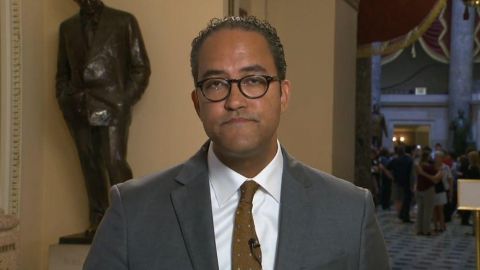

President Trump lights a dangerous fuse in a time of racial division, telling congresswomen of color to go back home. But why is his party staying mostly silent? Will Hurd, Republican congressman from Texas joins us.

Then, five years since Boko Haram snatched hundreds of Nigerian school girls from their dorms, journalist, Isha Sesay, with a new book about how this happened and why about half the girls remain captives.

Plus, seeing the future of our cities, our Walter Isaacson speaks to Richard Florida, editor of large of “CityLab.”

Welcome. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Today, the Trump administration is filing regulation that would make it much harder for migrants crossing the southern border to claim asylum. It comes just after U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement began raids targeting some 2,000 undocumented my migrants.

It’s a move the president had been telegraphing loudly only to be dramatically overshadowed on Sunday when he himself used what many believed to be some of his most racist rhetoric yet, tweeting that that four Democratic congresswomen of color should go back to the places they came from.

Leaders abroad and at home have condemned the message. Here in the U.K., the British prime minister, Theresa May called the comments completely unacceptable. House speaker, Nancy Pelosi, said, “Make America great again has always been about making America White again.”

The four in question are Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib. The only one not born in the United States was Omar who moved there when she was a 12-year-old Somali refugee.

I spoke about all of this with the Republican Congressman, Will Hurd. His Texas district abuts much of the southern border with Mexico, so immigration policy also literally hits home.

Congressman Hurd, welcome back to the program.

REP. WILL HURD (R-TX): It’s my pleasure. It’s always awesome to be on chatting with you.

AMANPOUR: Well, thanks, Congressman. And I obviously want to start with the controversial nature of President Trump’s tweet. I mean, you know, people are calling it racist, a firestorm, you know, lighting a fuse. It’s really hit a nerve even over this side of the Atlantic.

So, just to remember what he said, he said, “They originally come from countries who governments are a complete and total catastrophe. They should go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they come.” That is aimed at four freshman Congress people.

Nancy Pelosi has called it xenophobic. How do you describe that? Do you call it xenophobic? Do you believe its racist?

HURD: I think those tweets are racist and xenophobic. They are also inaccurate, right. The four women he is referring to are actually citizens of the United States, three of the four were born here. It’s also a behavior that’s unbecoming of the leader of the free world. He should be talking about things that unite us, not divides us. And also, I think, politically, it doesn’t help.

While you had a civil war going on within the Democratic Party, between the far-left and the rest of the party, now they have circled the wagons and are starting to protect one another. We can disagree without being disagreeable. I don’t agree with many of the things they are talking about and that – or (ph) proposals that they are putting forward, but that’s where the debate should be on, not these other issues.

AMANPOUR: Can I just ask you why you think the president keeps doing this kind of stuff, making controversial comments on Twitter and stoking certain flames? I mean, do you think the president is racist?

HURD: Well, you’d have to ask him those questions, but the comments were indeed racist. Look, I’m the only black in the Republican in the House of

Representatives. I go into communities that most Republicans don’t show up in order to take a conservative message. And when you have this being the debate, that activity becomes even harder.

And the only way we’re going to — you know, I’m from Texas. And I always say, “If the Republican Party in Texas doesn’t start looking like Texas, there won’t be a Republican Party in Texas.” And I think that goes for the rest of the country. So, this makes it harder in order to take our ideas and our platform to communities that don’t necessarily identify with the Republican Party.

AMANPOUR: So now, let’s talk about the other big issue and that is asylum and immigration and [13:05:00] detention and zero-tolerance policy and all of that.

So, what about now, the administration has petitioned to make formal what has been talking about a long time and that is almost no asylum in the

United States except via a third country?

HURD: Sure. That proposal was announced this morning. I do believe that our asylum laws should be tweaked. I think this move is probably going to get challenged in the courts. This is something that I’ve said, if we are going to tweak our asylum laws — or my (ph) asylum laws, it needs to be done in Congress.

And we need — and unfortunately, there are people that are taking advantage of our asylum laws. One of the other things that should stop happening is we should stop treating everybody that’s coming into this country illegally as if they are an asylum seeker. Not everybody is actually asking for asylum. And when the asylum laws are being abused, this hurts the people that actually need asylum laws. And when you look at our immigration courts, somewhere around 18 percent of people are the ones that, ultimately, when they go through the immigration system, the immigration court system, ultimately, gets – get granted asylum. And so, those are the folks that are being impacted. I do believe it’s time for the House and the Senate in a bipartisan way to try to address some of these issues. I have some proposals out there. But, again, I think this recent move is likely to get challenged in courts.

AMANPOUR: So, from what I hear you saying, you don’t support this new regulation?

HURD: Asylum laws is just one piece of the problem. The real long-term issue here is violence, lack of economic opportunity and extreme poverty in the Northern Triangle, that’s El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. We should have a special representative for the Northern Triangle, that’s a senior diplomat appointed by the secretary of state who should be working on the coordinating the strategy across the U.S. government with those three countries, but also work with the organization of American states, work with the International Development Bank.

This crisis is not just problem in the U.S. and Mexico, it’s a problem for the entire U.S. Western Hemisphere. And we need to get the entire Western Hemisphere involved. And I think that starts by creating, in essence, a Marshall plan for that region to address those root causes. That’s where we should be putting time and effort in.

And the other piece is human smuggling. If you’re coming through our southern border legally, you’ve likely paid $7,000 to a human smuggler.

And we are collecting information on phone numbers and data on those human smugglers, but the U.S. Intelligence Community is not doing enough in order to counter that.

We should be dismantling the infrastructure that these human strugglers have put in. And guess what, they are making more money because they are bringing more people in. And so, we need to be addressing that and working with our allies and all of those countries to do that. And I have a bipartisan piece of legislation that we’re actually introducing today with Abigail Spanberger, a Democrat from Virginia, to say we should be prioritizing and making — countering human smuggling and human trafficking a national intelligence priority.

AMANPOUR: Congressman, what about the ICE raids? I mean, I can see you pushing back on quite a few of these controversial issues that are coming out of the administration. You know, this huge sort of drum roll to what we were going to — told were going to be mass deportations, some people might have thought that was tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands, but maybe only, and I put that in inverted comments, 2,000. But it doesn’t seem that that’s happening.

First and foremost, do you support the notion of ICE doing mass deportations?

HURD: So, there are about 900,000 people in the United States who have gone through their entire immigration hearing and have been ordered to be removed from the country by a judge. So, ultimately, the United States, we should be enforcing our laws. But because we are dealing with this crisis right now at the border, we should be having all of our resources on the border to deal with the current crisis.

We don’t have enough folks in ICE, we don’t have enough folks in border patrol, we don’t have enough folks in HHS. And so, we should be

prioritizing our resources to address this current problem.

And I actually believe we should be getting to a point where, you know, last in, first out. The people that are more recently trying to come into the country illegal and should be deported, we should focus on them first. This is going to have more of an impact in those countries where they are ultimately coming from. And we also need more immigration judges.

I’ve tried to increase — you know, there is also a 900,000-person backlog in our immigration courts. You know, and the average [13:10:00] time it takes to get through these courts is over 600 days. I tried to increase the number of immigration judges in a recent appropriations bill and how we fund the government, and my friends on the other side of the aisle voted it down. We need more resources in order to deal with the problem that we are seeing on our southern border.

AMANPOUR: Congressman, a lot of the issues and a lot of the questions I’ve raised I see you pushing back against what might be called current Trump

Republican orthodoxy. And you do seem to be out of step with that sort of certain strain of the Republican Party.

I just want to ask you, you know, a couple of questions on this. You know, there’s a recent Texas monthly profile on you that said many conservatives have come to see you as guardian of the soul of the old party. You’re the old soul of the party. Joe Straus, Republican, former speaker of Texas

House said, “I think he is exhibit A in Texas for what the future of the Republican Party needs to be.”

Do you see yourself that way? And what do you think these old-timers mean by that? What are they yearning for?

HURD: Well, what I like to say, I’m the face of the future Republican Party, you know. And the future Republican Party, we are going to solve problems the way we have often solved them in the past. We should be empowering people, not empowering governments.

When you look at independents and conservative Democrats in the United States, they are concerned where the direction of the Democratic Party is going. And our opportunity is to appeal to those folks. In 2020, about a third of the electorate is going to be under the age of 29.

When you go back to Ronald Reagan, he won the under 29 vote by like 30 points. I think we can compete in these areas. That’s what I’ve demonstrated in a truly 50/50 district. My district, Hillary Clinton won by four points in 2016. And in the most recent election, Beto O’Rourke beat Senator Ted Cruz by five points, yet I continue to survive and win partly because, you know, I try to have a message that is reflective of where the majority of the country is.

Crisscrossing a district like mine, I’ve learned way more what unites us and divides us. And so, I try to talk about those this. And ultimately, Christiane, I — you know, spent nine-and-a-half years as undercover officer in the CIA. I’m a professional intelligence officer. You know, my entire adult life has been about collecting information and articulating that.

So, you know, I’m going to use those skills and those things I’ve learned and try to solve problems, not resort to the political rhetoric. And so, that’s how I’ve been able to perform and be successful.

AMANPOUR: Well, I mean, you have just laid out exactly the case that some people are making for you, particularly your background based in facts and evidence and intelligence, and then deciding on solutions and actions rather than just rhetoric.

But, again, I want to ask you because you do stand out. You are a Republican. And I guess I want to ask you, first, are you, yourself, surprised at what some people might say is a bit of a moral failure or a little craven of so many Republicans who simply have not stood up and said anything about President Trump’s, what you’ve just called, racist tweets?

HURD: Well, it’s concerning to me that there are people that think that is OK, that kind of behavior is OK. I’ve learned that — you know, my dad always taught me when I was young, the one person you can’t fool is the person you’re looking at in the mirror in the morning. So, be honest, treat people with respect and say what you mean. And that’s how I’ve always pursued things (ph) and then also trying to articulate alternatives.

So, you know, my goal is to be an example and, you know, ultimately, I think that is what I’m trying to do, but you’re going to have to ask some of those other folks. But it is something that we should look at is, why in 2019 do we think it’s OK to say some of these things? You know, this is — one of the things I’ve learned going to church on Sundays and, you know, I don’t care which faith you believe in, there’s some, you know, story to this point. And when Jesus was asked what is the most important commandment, he said to love thy Lord God with all of your heart, mind and soul. But he said equally as important is to love your neighbor like yourself. And I think we need to remember more of that, and I think we would be better off.

AMANPOUR: Let us gets back to this truly appalling situation at the border. We have had, you know, people from within the system are reacting against some of the more draconian measures undertaken by this White House, whether it’s zero-tolerance, whether it’s — also some issues by the census and all of the rest of it. [13:15:00] And now, of course, it’s about the children who have been put into, you know, unconscionable conditions in the

United States of America, including your state, this was in Clint, of course.

And we have had Vice President Pence visiting recently and seeing some of these literal cages which are overstuffed with people. There’s a little bit of the pool report says the stench was horrendous, the cages were so crowded that it would have been impossible for all of the men to lie on the concrete. When the men saw the press arrive, they began shouting, wanted to tell us they’ve been there 40 days or longer. The men said they were hungry, wanted to brush their teeth. It was sweltering hot. Agents were guarding cages wearing face masks.

You know, Mike Pence said he wasn’t surprised and shows that the system is overwhelmed. I mean, you know, yes, it is. But isn’t that, you know, cruel and unusual punishment for these people?

HURD: Well, first and foremost, let’s talk about Clint. Clint is in my district. This is a facility that I’ve been into. And Border Patrol has been saying this has been a problem since back in 2014, this real issue of the unaccompanied children. These are children coming to the United States without a family member. This has been a problem since 2014. And so, border patrol has been saying that.

You’ve had the Department of Homeland Security inspector general issue a report back in May talking about current facilities and then you had them issue a follow-on report on July 3rd. And so, these facilities were not designed for how they are being used. Clint, specifically, was designed to temporarily house 107 people. At its height, it had 700 children under the age of 18 in that facility. They can’t handle that.

ICE needs more resources. HHS — Health and Human Services is the federal government entity that’s responsible for caring for children, they need more resources. So — and many of my colleagues on the other side of the aisle want to vote against giving resources to these entities, they want to vote against increasing immigration judges, and then they show up to a facility that they are all saying is not designed for this and want to be outraged. That is the problem. We got to solve this issue. HHS has new facilities that are taking care of unaccompanied children. And right now, they are getting from when they receive them to when they get placed, it’s about 45 days. That is a decrease from, I think, it was 90, a number of months ago. These are facilities that just came online. There is one in my district that has about 200 children in it.

I’ve sent my staff down there to inspect it once it became online to make sure that the kids are being cared and fed properly. But this is a symptom of a much larger problem. And that larger problem, we already talked about is the root causes in those countries, asylum laws being abused and human smugglers increasing their activity. Those are the things that we should be addressing rather than having — using images as political bludgeons against one another.

AMANPOUR: Yes. But this isn’t just an image –

(CROSSTALK)

This is an actual fact and reality. You are based in fact —

HURD: Yes, I’ve been. Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: But I mean, the children there. Let’s just talk about the children, Congressman. It was a lawyer, a whistle-blower. She decided to go to the public because it was untenable. I just want to know whether you think that that is cruel for those children and that this administration has exacerbated this situation?

It’s all very well saying that the centers aren’t designed to house this number of people. But, you know, this is what happens when you separate children from their parents and don’t let them go to their carers who are already in the United States.

HURD: Right. So, I’ve been clear. Family separation, we are conflating several issues. Family separation, I’ve been very clear, you should never rip children out of their family members’ arms. That was a terrible policy. It was a policy that many people stood up and was against. But you have unaccompanied children problem which is different. These are kids that are coming here and they are not with a family member and trying to get them placed with someone who is actually a family member and going to not take advantage of them if they get placed. That is the current situation in a place like Clint.

And yes, nobody should be in these facilities for any length of time, let alone children, and these are things that shouldn’t be happening. And we should — and the only way you’re going to solve this problem is we have to make sure that the folks within the federal government have the resources to deal with the current problem and that we are addressing the root causes and not exacerbating it.

Don’t treat everybody as if they are an asylum seeker. That’s increasing the amount of people that are having to be in our custody. Deal with these root causes. This is how we’re going to get through the current problem.

We are seeing a dip in people coming here illegally. It may just because usually in the summer you see a dip. We are seeing our allies in Mexico having to deal with this issue as well. They are taking separate steps. How long that can continue? These are the questions. And then also we need the rest of the Western Hemisphere to get involved in trying to deal with this problem.

AMANPOUR: And a huge problem, it is. Congressman Will Hurd, thank you very much for joining me.

HURD: Always a pleasure.

AMANPOUR: So, from that really appalling situation with children at the southern border, we now turn to a story about children that’s been buried by the relentless place of U.S. political stories. Five years ago, not many people would have known what or where Chibok was, a small town in Northeastern Nigeria. It was catapulted to global infamy in 2014 by a disaster and a hash tag. Here is reminder of what happened.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Covered from head to toe, dozens of mostly Christian girls were forced to chant from the Quran. This was the first glimpse of kidnapped Chibok school girls, after 276 were snatched from their school dormitory by Nigeria’s Islamist group Boko Haram. That loosely translates as Western education is forbidden.

Fifty-seven of the girls managed to escape in the hours that followed. The rest remained captives of the gunmen. Under the hash tag “Bring back our girls,” their plight spread like wildfire on social media, from Malala Yousafzai to then First Lady Michelle Obama who said she saw her own daughters in these girls.

Two years later, a rare glimmer of hope for some of the families as CNN obtained an exclusive proof of life video showing 15 of the girls, it took two years to get just 21 of them released after negotiations between the government and Boko Haram.

Isha Sesay was there for CNN when they reunited with their families in Chibok. But for so many parents, there was still only heartbreak.

ISHA SESAY, FORMER CNN CORRESPONDENT: The piercing screams of mothers realizing that indeed they are not to be reunited with their daughters on this day, which has turned what should have been an overwhelmingly happy moment into a bittersweet one.

AMANPOUR: More than five years on, 107 girls have made it out of captivity. 112 are still missing. And as the campaign to free them fades with time, endless grief for so many of the families.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now, Journalist Isha Sesay who you saw in that report has just written broken a book on the Chibok girls, it’s called “Beneath the Tamarind Tree,” and it follows her time covering the story as it hit global headlines and its unprecedented access she’s has to some of the kidnapped girls. And Isha is joining me now from New York.

Welcome to the program.

SESAY: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: So, Isha, just from — pick up where we left you in that little report there, you know, time is moving on. Lots of parents have been deeply disappointed, still in grief and suffering. Do you see any possibility that this is going to be resolved or are we really, you know, hostage to time erasing the urgency?

SESAY: I think to some degree we are hostage to time erasing the urgency and the Nigerian government that is beset with a multitude of problems, not only battling Boko Haram, which one faction is now aligned with ISIS and continuing to terrorize Nigeria, Chad, Niger and Cameroon. But also, that the other issues such as kidnappings that have basically proliferated across the northwest of the country, issues to do with the cattle herders and farmers in the middle belt and the Niger Delta.

So, the Nigerian government has a number of issues on its plate. But there’s also just an issue of political will here, Christiane, in the sense that, as you well know from covering this at the time, that these girls come from poor families, from the north, out of the way, uneducated and they just aren’t seen as a priority to this government.

And as far as they are concerned, they have done what they can to bring 103 of the girls back. The four others escaped. And for the rest, I think there’s this kind of shrugging of shoulders, Christiane, to be perfectly honest.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you then about the girls, because the book — well, I’m going to ask you why you called it “Beneath the Tamarind Three.”

But the girls, it was very rare to see girls abducted by these Islamist groups and it’s — I find it very interesting that you called this, having talked to a lot of them, a crime of opportunity.

SESAY: Absolutely. I think that is one of the biggest misunderstandings about what happened. Because from the research I have done and speaking to the girls, when the men arrived [13:25:00] in the school that night, they set upon the goals with a host of questions. You know, they asked about brick making machine, they asked about fuel, they asked about food and where that was kept.

And when it came to actually move them — when they said actually leave the school compound and let’s step out because they were burning the buildings, there was a conversation that a number of the girls told me about and the conversation was essentially, “Should we take them or should we put them in the burning rooms and kill them?” So, there was an actual debate. So, they didn’t come with the preorganized plan, if you will, to take them.

And that is something I never knew until I did the research for this book.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And I had not known that either. And I find that really, really interesting. And just to go back to the slogan, Boko Haram, you know, Western education is prohibit, is forbidden, is unclean, that’s their basic concept. I mean, it sorts of circles back to your connection and your interest in this because, you know, you spent a lot of your youth in Freetown, Sierra Leone, your mother is from there. And education was a massively important vehicle for her and for you not to, you know, end up poor and potentially subject to this kind of captivity.

SESAY: Absolutely. You know, and I say to people who continue to ask the question, why is this story so important to you? Why does it seem so personal to you? Because I say but for lottery of life but for the fact that I was born to educated parents. My mother was born to poor Muslim parents. My grandfather was a religious man, he had multiple wives and he was uneducated. My grandmother was uneducated. She sold goods in the local market in their town, which was very similar to Chibok, poor, no plumbing, no power in most of the houses.

But my mother, despite not having, you know, examples of educated people in her family, went on to be very educated, have a PhD in English language and linguistics and to run for vice president in Sierra Leone. Because of her accomplishments, I have the life I have. And I understand that the girls in Chibok were on the same path my mother walked, a path of becoming educated and transforming their lives, their parents and potentially their children’s lives. So, this hits home for me.

AMANPOUR: And it’s very clear because, as I say, you know, the strongest passages are when you talk to them and you listen to them and, of course, the parents as well and the families as well. But I just want to read a piece, a little piece of what you wrote about your mom and circle it back to these girls. “Everything in Sierra Leone’s patriarchal society directs women and girls to be quiet, docile and subservient to men. But with Kadi as my bulwark, those norms never infiltrated my childhood.”

So, Kadi is your mother. And I wonder whether when you were talking to these girls, did you get a sense that patriarchal direction subservient affected them when they were kidnapped or did they have more of a fighting spirit? Did they resist? What did they think when these guys kidnapped them?

SESAY: You know, it’s really interesting because on the one hand, yes, they are children from the northeast. So, they are a product of that patriarchal conservative society. So, even when you meet them now, if there is an elder male in the vicinity or speaking to them, as soon as they meet, they kind of curtsy, they dip their heads as a sign of respect. They do keep their eyes, you know, down to the ground. They do still some of those traits.

But for all of that, when he this were in captivity, Christiane, what is remarkable were the acts of defiance and the way they pushed back in the moments that they found this untapped bravery, if you will, to say, “When can we go home? You said we would be able to go home and you’re holding us. Why are you holding us?” Refusing to bathe became a kind of personal act of disobedience. Keeping journals, some of them were able to do that.

Some snuck away with bibles and continue to practice their Christian faith even though their warned if they were caught that could lead to horrible consequences.

It is remarkable that in the midst of that culture of subservient they still held on to their strength, they still held on to each other and, you know, they didn’t just capitulate, and that, again, truly surprise me and hasn’t been told as part of their narrative.

AMANPOUR: I still find it extraordinary. I mean, obviously, we are focusing on those who are still captive. But, as you said, I think you said 103 — how many? How many actually escaped?

SESAY: So, the Nigerian government — so, there are 107 who are out now. The Nigerian government negotiated release for 103 of them. Four of those girls escaped on their own.

AMANPOUR: That must have been really difficult. I mean what did they tell you about actually having the guts to get up and run away?

SESAY: Now, for the book, I didn’t speak to girls who escaped after being in captivity. I spoke to girls who escaped in the hours after the abduction. And so for those girls, one of whom jumped off the truck as it entered the forest.

And another girl who ran away when they stopped for their first rest break. You know it was incredibly terrifying for them. And one of the things they kept saying was even though they knew there was a chance that they may die, that if they were discovered — if the captors caught up with them they would be shot and killed; they decided that they would rather make a break for home.

Try to escape. And at least give their families a chance of finding their dead bodies than potentially being held captive and their families never finding them. And — and again, you know I think one of the other reasons I wanted to write this book is because there is a kind of normalizing of — of — of tragedy and — and pain from the African continent.

And so for the abduction of these girls, as much as people were shocked, there was also kind of well it happens in Africa. Lots of bad things happen in Africa. And I wanted people to understand the bond between these — these young people and their parents.

I wanted them to understand the loss, the grief, and when you speak to the girls they so vividly tell you about the anguish they felt at being taken from their parents and why some of them chose to run.

AMANPOUR: Tell me about the title and the Tamarind tree in the title.

SESAY: So “Beneath the Tamarind Tree,” and this again is indicative of the process of getting them to open up to me. I spent many, many months — well over a year doing research and going back and forth to Nigeria and speaking to the girls.

And it wasn’t until 2018 — having already started the research for this book basically fully and consistently at the beginning of 2017, it wasn’t until 2018 that they opened up and told me about the moment they arrived the forest in Sambisa at the Boko Haram camp and they were — they were told to get out of the vehicles and to go under a tree.

And I remember thinking what — what do you mean go under that tree. I asked several times. And they said there was this giant gargantuan tree that was so overgrown with leaves and fruit and bowed almost.

It created something of hooped skirt because the branches hit the ground and they were told to part the branches and go under the tree. So they were basically hidden beneath this Tamarind tree.

AMANPOUR: From any surveillance or any — any — any military operation to try to get them.

SESAY: Exactly.

AMANPOUR: Let me ask you about one of the Moms, Ester (ph), you — you focused on. Now she had a particularly tragic situation because — and we have a video. Her girl, at least in this propaganda video said that she had converted to Islam and she wasn’t coming home. What kind of torturous sort of emotions did you encounter with — with the parents.

SESAY: Interviewing Ester (ph) and every time I speak to Ester (ph), it is — it — it leaves me so incredibly pained because even speaking about it now because her level of anguish and what it has done to her family is — is just so — so difficult to bear witness to.

Dorcus (ph), her daughter here that we see amongst these girls, she was the youngest of the girls to be taken. She was 15 about to turn 16 and she’ll shortly turn 21. And you know for Ester (ph) — and again, one of the things I do in this — this — this book is try and tell the stories of these girls as — as girls as their favorite possessions and their habits and hobbies.

And Dorcus (ph) was a very prim and proper child who caused no trouble and was really jus the focal point of the family. She was going to go on and get a degree. Her mother had placed all her hopes in her child going off to university only for her to be snatched by Boko Haram.

And the family is just broken. She — she can’t sleep, she can barely eat, she’s developed an ulcer, she has high blood pressure, and they’re just utterly distraught. Seeing that video with her daughter saying — again, one doesn’t know whether she said it freely but it’s a propaganda video regardless.

Hearing her say she doesn’t want to come back that effectively she’s with believers and doesn’t want to come back to — to non believers broke her heart — you know it broke her heart.

But I messaged her a couple of days ago about the book and I said you know my hope is that this will recharge the conversation about the missing girls. And she said God will make her way one day for my child to come back.

AMANPOUR: Well that’s faith, isn’t it. And Isha, thank you so much for reminding everybody that some many of these girls still remain in captivity. Of course we’ve said that it’s important to remember the story is far from over.

Five years on, 112 gears are missing still. And their parents, as you just heard from Isha Sesay, suffer endless heartbreak. And now let’s turn to what our next guest calls the new urban crisis.

Richard Florida is a leading urbalist. He’s a professor and also an author. And he says America’s biggest divide is not red versus blue but rather city versus suburbia; arguing that where we call home is one of the most crucial factors effecting where we sit in the social ecosystem.

He joined our Walter Isaacson to map out the state of urban hubs today from income inequality to big tech.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: You’re a great urban study scholar and you helped invent the notion of the creative class and how that was going to revitalize American cities. Explain what that original notion was.

RICHARD FLORIDA, AUTHOR, “THE RISE OF THE CREATIVE CLASS”: So here’s — here’s where it comes from; I — I was born in Newark in the late 1950s. I watched Newark decline and decay. I saw the city jobs and industry move to the suburbs.

I actually witnessed the national guards and tanks in the street. When I was a young scholar no one believed that cities could come back. So fast forward. Now it’s the late 1980s and 1990s. I’m living in Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh was hit hard by deindustrialization.

What could begin to revive cities — what I began to see was in places like New York, in San Francisco at the time, in Boston there was this group of people; scientist, technologist, start up people, artist, musicians, professor types who were coming back to cities and I couldn’t explain it.

That’s where the idea of the creative class comes from.

And when we put the numbers to it, about the year 2000, what we found is that this group of people, which was less than 10 percent of the work force when I was a boy, grew with third of the workforce and in big cities these scientist, techies, business managers, knowledge workers, and artist were now 33, 40, 45 percent of the workforce.

So that is the creative class and it is the force, like it or not for good and bad that has revitalized many of our cities.

ISAACSON: And because they moved into the urban core more than they would go to the suburbs.

FLORIDA: Yes. And I think what happened really is that — you know I wrote this book in 2002, so it’s a quite a ways — a time ago. And after about 2000, this urban rival just goes on steroids.

And — and these folks begin to cluster in cities not just because they like cities, not because they just had great parks and amenities and universities and coffee shops, what the economist have found is the cities — they’re clustering in cities (inaudible) drives economic growth, creates innovation and productivity but they don’t cluster in all cities.

Now they have gone into many cities but they tend to cluster in these superstar cities like New York or Los Angeles or London in the U.K. or these big tech ups like San Francisco or Seattle or Boston or maybe Washington D.C.

ISAACSON: You got some push back from people like Joel Kotkin who said OK, it’s a great theory but the numbers don’t show it. The data’s not there, people actually are moving to suburbs, not cities. What would your answer to that be?

FLORIDA: And it’s funny because Joel has become, believe it or not, a great personal friend and we have had some of the most vicious fights but I told him, I literally said Joel, I’ve learned about as much from you as I’ve learned from anyone else.

Look, the creative class can thrive in suburbs. And — and — and we did the data later. We started with metros, right, the suburban urban glomerations. When you look at the data there are some suburbs — you know even in — in the outskirts of Detroit; suburbs like Royal Oak and Birmingham that have very high clusters of the creative class.

I don’t think it’s an either/or, it’s a both. But here’s the point, it’s not everywhere. It’s in certain suburbs, it’s in certain cities, it’s in certain big cities, it’s in certain small cities and it’s where those places have the attributes that can engage this clustering.

ISAACSON: You began to see after “The Rise of the Creative Class” came out. Some of the downside of this sorting in America, so what did you do?

FLORIDA: So me and a guy named Bill Bishop actually worked together. He wrote this fantastic book called “The Big Sort.” So we were in .

ISAACSON: And explain what this is because it’s about (inaudible) .

(CROSSTALK)

FLORIDA: For folks watching, is the idea that in America, this is way before Trump, that we were becoming more divided, not only red and blue, we were sorting into specific kinds of communities that engaged us economically but reflected our political and cultural biased. And that those divisions — now we were talking about this is 2002.

We’re expanding overtime and I think neither one of us — certainly I could never have anticipated how big this would go. So what happened was — when you mentioned, I took some great criticism, as you do.

When you write a popular book people read it and they criticize it. I learned form that but the world changed. The world that I was envisioning of a optimistic, rosy eyed revitalization, coming back to the city in an open-minded environment became very one sided.

And parts of cities, not all cities, became, like, gentrified colonies, and our cities began to split apart. You know, this happened on steroids, beginning in 2000, accelerating after 2010.

The reason I came to this is, I was living in toronto where I still spend a good part of my time, and this crazy crack mayor, Rob Ford, got elected, and I was thinking “In Toronto? Toronto the good? Toronto, the place that has healthcare for all, that has invested in transit, at least up to that point, that had safe streets and no gun — very little gun crime? Why would they elect this populist This is a test 08:25:06 Real time before Trump?

Because the creative crass, my creative class, was colonizing the inner city, taking advantage of the great locations close to the university, close to downtown, making money off their housing as it went up, and working people and the people who worked in those low-end service industries were being pushed out, and our community, just like our country, just like America, was becoming more divided. That’s what I began to see as contradiction of the creative class.

ISAACSON: And it led to a greater inequality of wealth that became part of the resentment, right?

FLORIDA: You know — and we actually documented this in 2002 and 2003 for essays I wrote, for, at that time, the “Washington Monthly.” You see in these creative cores, in San Francisco and Austin and Seattle and Boston and New York, inequality was the greatest in the nation. But when I came to write about this sequel book, “The New Urban Crisis,” what I found was this contradiction — the more diverse, the more dense, the more innovative, the more open minded, the more liberal and progressive, more votes for Obama, more votes for Clinton, whatever, the more inequality and more segregation.

And that contradiction was what I wanted to focus on.

ISAACSON: Why does that happen?

FLORIDA: Because of the big sort. Because of this sorting of us by economic status, by class position, by level of education, we are becoming a very sorted country in which the advantage folks cluster. It can be urban. And there are still many, many advantaged folks in the suburbs of New York, in the suburbs of California, in the suburbs around Boston.

We can sort into urban centers and suburbs, but the places we sort into become so darn expensive. You know, look at housing prices in New York or San Francisco or Los Angeles, that less advantaged people, lower skilled people, working people are pushed out.

ISAACSON: So tell me about the book, then, that you wrote, that tried to explain that problem.

FLORIDA: Well, you know —

ISAACSON: Was that a walking back of your earlier book?

FLORIDA: I don’t — I don’t think it’s so much of a walking back as recognizing that things have changed, recognizing some mistakes that I made, and really trying to interpret the world as it evolved. And here’s what it was; it kind of tracks the arc of my life. A kid born into the old urban crisis in Newark and New York City, you know, Ford (ph) declaring the city drop dead, you’re in bankruptcy, go away and crisis failure, a crisis of complete and total urban failure.

A company is moving out; people moving out. A whole — they called it, in urban studies, a hole in the doughnut. Then to see this revitalization come, slowly at first, and then flood gates open after 2000, but the new urban crisis isn’t a crisis failure. Ironically enough, it’s a crisis of urban success — it’s a crisis of urban success. The more these cities attracted talent, the more they attracted the creative class, the more they gentrified, the more uncool they became with other parts of the country and within themselves.

So — and what I argued in the book is the new urban crisis isn’t just a crisis of cities. When you see it play out on the electoral map in this divisions of this country, which you know so much about, it’s kind of our crisis of our moment of Democratic capitalism. IT really is, how do we put these two parts of our economy, the creative centers and rest of the country, back together? Can we?

ISAACSON: So what should we do about gentrification?

FLORIDA: Well, I think — you know, look, there’s a couple of things that people or policymakers and academics and thinkers are talking about. First, there is no doubt we need to build more housing where we need it — not out in the far-flung exurbs. We need to build more housing in the core and in those old suburbs, you know, which have the single family homes that can be densified. To do that, we’ve got to liberalize our use prescriptions (ph).

Number one, some people, so-called “market urbanists,” who I admire a lot, think that’s sufficient. I think it’s necessary, but insufficient. I think we’ve got to commit to building affordable housing. In New York now, we have a program, in this city, where if you’re going to build a new tower —

I forget the exact fraction, but it’s between 20 and 30 percent of those units you can’t buy out.

In that new tower, that new luxury tower, have to be devoted to affordable housing. We have to build more transit to connect people out in the suburban areas, and especially those close in suburbs, and densify around the hubs. And I think the last thing we need to do, which few people are talking about, Walter, about a third of now of us in America have the great, good fortune to be members of the creative class.

We make a pretty good amount of money, even the artists and cultural works, never mind the scientists and techies. More than half of Americans work in low wage, crappy, precarious service jobs.

Condemned to a life almost of disadvantage, almost poverty. When we decided to build the middle class in this country, we made manufacturing work good work. My used to tell me, he worked in a factory. He started that job in the depression. When he came back from World War II, FDR, the new deal (ph), his job became a good, family-supporting job. He could buy a house in the suburbs.

He put my brother and I through college. Service works can’t do that today. They are working at — you know, if Karl Marx was back to life, he would say, they’re working in immiserated, sustenance conditions. We need a national effort to upgrade the 50 percent of low wage service jobs and food service preparation, retail work, office work, that are the backbone of our economy, but people are sinking further and further into poverty.

ISSACSON: Do you think, in some ways, capitalism is broken when it comes to a market economy in cities like that?

FLORIDA: Well, in my field — my field, we have a long tradition of Marxist, post-Marxist analyst, and a lot of critics come from that part.

They want to envision — and I learn from these people, particularly a guy named David Harvey (ph), who’s absolutely brilliant. But there’s a hope for a kind of socialist utopia that doesn’t come.

So pragmatically, yes, capitalism is broken. What do I believe? I think we have to go about fixing it. How do I think we can best fix it? If we could just empower our cities to begin to address these problems, and why I think it works is because cities are in gated suburbs. No matter how gentrified

New York or San Francisco become, there are still poor people. There are still ethic and racial minorities. They are still progressive political actors who act on politics.

So I do think our cities are going to be the place, they’re going to laboratory of Democracy, that figure out the way to create a new social compact that can make this kind of capitalism work. I shutter to think at what the alternative might be.

ISAACSON: But if we empower cities, would that leave some people, like the people who live in suburbs or exurbs or in the countryside, leave them out?

FLORIDA: I think it might leave people in the reddest parts of the country out. But here’s the way I figure it, and I’ve talked to the leading theorists this — about this, both on the left and the right. Look, we don’t agree on many things in this country. We don’t agree on gun rights.

We don’t agree on women’s rights. We don’t agree on gay rights. I could go down the litany. And already, state preemption is taking a lot of those rights away. \

ISAACSON: Well, explain what that is.

FLORIDA: Well, states, you know, across this country are saying, because they’re run by rural and suburban majorities, we are going to prohibit you from acting to control guns. Bill Peduto, the mayor of Pittsburgh, who’s is a good friend of mind, has several pending civil suits and maybe a criminals case, from the Pennsylvania state government, that says he’s acting too quickly on gun control. Gay rights are another one.

ISAACSON: And minimum wage.

FLORIDA: Minimum wage is another one. Although, we see more red states, interestingly enough, at least be able to raise their minimum wage somewhat. So I think this is happening. What the best theorist of the so- called “federalism” — you know, the United States is a federal system where we can adjust the relationship between the federal, the state and local governments say.

Yes, Walter, that’s a risk in the short run. Yes, that’s Richard, that’s a risk in the short run. Over time, though, these states and cities have to compete. So what’s happening in Georgia now under the threat of these new women’s rights bans and gay rights bans, the Hollywood companies are saying, we’re going to have to pull the films that are being made in Atlanta.

We’re going to have to bring them back to a city that doesn’t impose that. So the theorists say, this competition for economic growth, well (ph), the same thing I see when I go to Texas. The business people are saying to the governor, stop it. We can’t attract an Amazon HQ two if you keep up this kind of red state looneyness, in terms of social policy.

So the theorists believe that this competition between jurisdictions may lead to some places running to the bottom in the short-term, but over time, the competition will lead to better outcomes.

ISAACSON: When you look at the big (inaudible) that you and Bill Bishop have talked about, one of them is these cities and they become (ph) enclaves of creative people, and then the areas just around them. You can look at Austin, Texas, going 90 Democrat, and same with Houston, but there’s — right around it, go 90 percent for Trump. Are we dividing our country based on the new urban elite versus the rest of America?

FLORIDA: Yes. And these divides are fractal. A big word, big word, fractal. They occur at every scale. They occur between the costal elite places like the New York, Boston, Washington Card (ph) and the Southern and Northern California, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle.

But then even within those places, those divides replicate. I mentioned Toronto earlier. Toronto’s a very progressive place. It’s a very blue place, but even within it, there’s red and blue, liberal and conservative. And the way I like to think about it is, the knowledge economy or creative economy is very spiky. You know, Tom Friedman had a wonderful book that said the world is flat. For many things, manufacturing, simple service, the world has flattened completely.

But within that flat world that Tom explained so brilliantly, there are these spikes, and what happens is these spikes take on a different character, a different economic character, a different political character and a different cultural character. And the backlash is not so much about the economic inequity, it’s about the cultural norms and values.

If you live in an urban center you tend to not want to have guns around you. You want safety. You want to be open-minded to all those people who are contributing to your economy. You want to be pro-immigration and pro- women’s rights because women make up, believe it or not, more than half the creative class is made up of women.

Just like more than half economy — population is made up of women. But the creative class has much greater numbers of women than say the working – – the physical working class. But if you live in one of the places in the outlying areas and you’re a white middle aged man, you feel threatened.

You feel threatened by diversity, you feel threatened by women, you feel threatened by the fact that women and immigrants have gotten, in your view, a leg up. You feel threatened by the sexual and gender revolution and it creates that backlash.

So I think that backlash is not just between parts of the country. Yes, it’s between parts of the country but it’s within parts of the country as well.

ISAACSON: So in other words between counties and parishes (ph) or something where you have people who are very comfortable with diversity, very comfortable as a creative and knowledge economy and people who may feel that they’re being looked down upon or — by the elites.

FLORIDA: And so we have a divide in this country but it’s not the old — people get mistaken, it’s not the old North/South divide, it’s not a frost belt/sun belt, it’s not an east/west, it’s a new kind of divide that’s very spiky — big word — very fractal, very concentrated but I — but I think we’re about even split.

You know there’s about half of us that are populating one and that takes the creative class and some of the new immigrant groups. And about half the country that’s populating another and sometimes we live quite closely.

Here’s an interesting fact though. There’s a brand new study out that — that I found so amazing and — and hardened me for a moment you know in times of others views may think are dark.

This was a group of political scientist who know a ton about the big sort that we’ve been talking about and who studied the sorting of Americans. And not just Americans, they’ve looked at the most sorted of us, highly active liberals and highly active conservatives.

On national issues, which we’ve talked about; gun control, social issues, women’s rights, abortion; we are worlds apart. When they poll those same people on local issues; do you want your economy to grow, do you want good schools and they went down — I’m giving you big — almost complete consensus.

And that gave me hope that when we’re closer together and focused on our local communities and get out of this chamber — this echo chamber of national issues — when we’re focused on hometown — you know Mike Bloomberg used to famously say you couldn’t tell if a mayor is — what was it, there’s no liberal or conservative, republican, or democratic way to pave the street or to deal with .

ISAACSON: Pot holes have no party.

FLORIDA: Yes. Pot — thank you. Pot holes have no party. And I think that really is the case. You know I — when I meet with mayors and I work with a lot of them, it’s very hard for me to tell and it’s very hard for me to tell who’s a republican or a democrat.

So I think that hardens me. When we look at the local issues and get out the echo chamber of national issues, these — these — these high potency national issues, I think we’re a lot better to solve our problems.

ISAACSON: And so what policies would you do to try to knit the fabric closer together?

FLORIDA: So I don’t think we can. I think we’re really divided. And I think divides gotten worse over my life. You know and I’m 60 ish years old. I think we’re going to have to realize that we are best served by living together as two Americas.

And the way to reduce — I think Trump proves how problematic the imperial presidency — we — we knew it — people like you and I knew it but until you had someone who really wasn’t up for the job, you couldn’t see it.

Now you can see how problematic that institution — so what we do is take our federalist gift, this distribution of powers that we’ve dialed up.

Right. Over the past 50 years since the (inaudible) we have dialed up the power of the federal government and we begin to dial it down.

No, we don’t give all power back to the communities — and I don’t mean just the cities. We give power back to the suburbs and rural areas. We give them their tax power back, we give them their economic power back, we enable them to build their own and we enable them to create the kind of cultural context.

You know look, here’s a statistic. About 20 so percent of us live in urban areas. I forget what it is. 60 ish, 70 percent of us live in suburban areas and the rest live in rural areas. The over whelming preponderant (ph) like where we live. We vote with our feet. America we vote — that’s what the big sort is. We vote with our feet to be in the kind of places that reflect the cultural and social political context we want to live in. So let’s not avoid that. Let’s not spend every four or eight years screaming and yelling at one another.

Let’s admit that we are two or more countries and let’s live together peacefully. Let’s create a united — (inaudible) a united cities of America — I’m trying — united communities of America, united places of America it won’t be perfect but it will be a lot more robust and resilient because we’re much more successful when we distribute in any kind of system than when we concentrate it.

And I think if we reduce the stakage (ph) around these national issues, we’ve have a somewhat better chance of being able to get along.

ISAACSON: Richard Florida, thank you so very much.

FLORIDA: Thank you for having me, Walter.

ISAACSON: Appreciate it.

FLORIDA: It’s great to spend time with you.

(END VIDEO TAPE)

AMANPOUR: And hope does spring eternal. Thanks for watching “Amanpour and Company.”

END