Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: I find it very interesting that you called this, having talked to a lot of them, a crime of opportunity.

ISHA SESAY: Absolutely. I think that is one of the biggest misunderstandings about what happened. Because from the research I have done and speaking to the girls, when the men arrived in the school that night, they set upon the goals with a host of questions. You know, they asked about brick making machine, they asked about fuel, they asked about food and where that was kept.

And when it came to actually move them — when they said actually leave the school compound and let’s step out because they were burning the buildings, there was a conversation that a number of the girls told me about and the conversation was essentially, “Should we take them or should we put them in the burning rooms and kill them?” So, there was an actual debate. So, they didn’t come with the preorganized plan, if you will, to take them.

And that is something I never knew until I did the research for this book.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And I had not known that either. And I find that really, really interesting. And just to go back to the slogan, Boko Haram, you know, Western education is prohibit, is forbidden, is unclean, that’s their basic concept. I mean, it sorts of circles back to your connection and your interest in this because, you know, you spent a lot of your youth in Freetown, Sierra Leone, your mother is from there. And education was a massively important vehicle for her and for you not to, you know, end up poor and potentially subject to this kind of captivity.

SESAY: Absolutely. You know, and I say to people who continue to ask the question, why is this story so important to you? Why does it seem so personal to you? Because I say but for lottery of life but for the fact that I was born to educated parents. My mother was born to poor Muslim parents. My grandfather was a religious man, he had multiple wives and he was uneducated. My grandmother was uneducated. She sold goods in the local market in their town, which was very similar to Chibok, poor, no plumbing, no power in most of the houses.

But my mother, despite not having, you know, examples of educated people in her family, went on to be very educated, have a PhD in English language and linguistics and to run for vice president in Sierra Leone. Because of her accomplishments, I have the life I have. And I understand that the girls in Chibok were on the same path my mother walked, a path of becoming educated and transforming their lives, their parents and potentially their children’s lives. So, this hits home for me.

About This Episode EXPAND

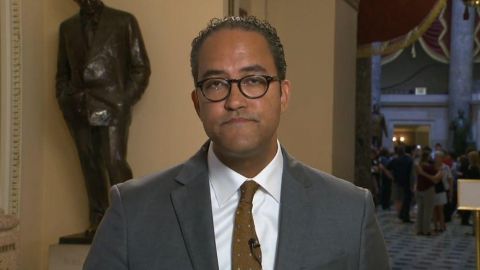

Will Hurd sits down with Christiane Amanpour to discuss what many believe to be President Trump’s most racist rhetoric yet. Isha Sesay joins the program to discuss the 2014 kidnapping of hundreds of Nigerian schoolgirls by terrorist organization Boko Haram. Richard Florida tells Walter Isaacson why America’s biggest divide is not red versus blue, but rather city verses suburbia.

LEARN MORE