Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And as we said, the number of global refugees has hit an all-time high. Severe food shortages, a byproduct of climate crisis displaces millions of starving people around the world. Now, as Amanda Little tells in her new book, “The Fate of Food,” our heating planet is drastically changing the way we break bread, from cloned cows to edible insects, our Hari Sreenivasan checks out what may be on the menu of the future.

HARI SREENIVASAN: So lay out the problem in case for us. Where are we headed with global food supply and demand?

AMANDA LITTLE, AUTHOR, THE FATE OF FOOD: So the central paradox of our food future is essentially that we’re seeing huge increases in population. We’ve heard 9.5 to 10 billion by mid-century. And at the same time, pretty significant threats to global food supply. So the International Panel on Climate Change predicts that we’ll see, I think it’s two to six percent decline in crop production every decade going forward because of different climate change pressures. And they range pretty dramatically from drought and heat to flooding to shifting seasons confusing the plants to invasive insects. And that sort of contradiction, right, of increasing demand, decreasing supply, poses this really interesting challenge to farmers, as well, as engineers, and all of these other folks that are sort of joining this effort to address food security.

SREENIVASAN: This book isn’t necessarily a pessimistic look. You’re actually spending a fair amount of time looking at ways that we’re trying to solve this, and some of them which are scalable.

LITTLE: Yes, this is interesting. A lot of the response has been this book is really optimistic. And that’s been a bit surprising to me, because it, it felt like very hard earned optimism. And I am very interested in the way in which sort of our survival instinct is kicking in and we’re beginning to see that platonic maxim, “Necessity is the mother of invention,” right? The pressures to evolve and adapt, in this sort of — to these new realities, are certainly driving really exciting innovation. And so chapter by chapter, I explore things happening that are very new — radically new in areas like artificial intelligence and robotics, CRISPR, and gene editing, vertical farms, and so on. And also some really old ideas like permaculture and edible insects and ancient plants. And so, you know, it’s not all just tech will save the day. But it’s more how can we blend sort of strategies that are both traditional farming practices, and also these radically new approaches that are coming online.

SREENIVASAN: You can break the book or the structure down into three or four big parts, and we’ll try to go through those. First, let’s take a look at kind of plants and crops. You start out in chapters where you’re talking to an apple farmer in Wisconsin, and you’re seeing the real effects that are happening on his land now —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDY FERGUSON, FARMER: It takes a special kind of person to grow apples. You’ve got to be able to roll with the punches that Mother Nature throws at you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

LITTLE: It was important for me to start out this book in an apple farm in Wisconsin. I traveled to a dozen countries and probably 15 states, and you know, I was excited to tell some of these far-flung stories, but I wanted it to begin sort of, you know, at home, really, and I heard about farmers growing apples and cherries and peaches and citrus all over the country dealing with these– what they call total kill events — which is early blooming in these orchards because of warmer winters. And then a normal freeze comes along and April or May, and kills off these mature blooms and emerging fruits.

SREENIVASAN: The trees are confused because it’s so warm, they decide, oh, this must be spring and they blossom and they lose all that protection from the winter.

LITTLE: That’s right. But you know, what I learned from Andy Ferguson, who is this young farmer, you know, he was saying that the risks that I have to mitigate, you know, are far greater. He is actually separating the land that he farms, so, that if there’s an extreme weather event in one region, he knows that the apples he is growing in another region might not have had that hailstorm or a total freeze, a freeze event.

SREENIVASAN: He is not putting all those apples in one basket.

LITTLE: Right, not putting all those apples in one basket. Exactly. And that was the beginning of this broader story was, what are these impacts first of all? And what are the ways that are, you know, sort of obvious, and also very subtle and unexpected that climate change is beginning to affect our food system. And along the way, as I ate Andy’s apples or traveled to a tiny corn farm in Kenya, or to a giant fish farm in Norway, I began to sort of get this recurring kind of message that climate change is becoming as something we can taste. It’s an issue that for so many of us feel so far flung that we associate with melting ice caps and polar bears, and it is that. But it’s also beginning to sort of affect us in these very intimate ways. And it’s becoming in that sense a kind of kitchen table issue, you know.

SREENIVASAN: And it’s not just anecdotal from Andy’s life, you’re actually pointing to a different research that’s being done, and has been done going back through records as far as they’ve been kept. And you can see the change in volatility of the weather and how crazy the freeze events are, how much more frequent they are. I mean, Andy’s life as a farmer has been affected and is continuing to be so.

LITTLE: It’s such an important point. You know, at a time when we have politicians making decisions and essentially launching an assault on climate science, there’s so much research that’s coming up. As you know, one of the scientists I interviewed at, I think it’s University of Michigan told me, the data is telling a story. You know, another scientist said to me, we have one horticultural blood on our hands. You know, these plants are telling us a story, and they’re telling us a story of sort of chaos and confusion and real trends that we can track over time through the story of food.

SREENIVASAN: As more people come online, they don’t automatically just become vegetarians. They also want protein in their diets, and meat consumption is probably one of the most ecologically intensive things, energy-wise that we have on the planet and that’s — what you start pointing out is there’s more effect that we have through meat consumption on climate change than we do from driving or flying.

LITTLE: This is an important transition from — and we’re talking about crops and vegetable and grain production to proteins. And there’s a very intimate connection. More than a third of all the grains produced goes to livestock production, right? So, what happens is, the changes that are affecting our fields is also affecting the farmers who are raising our meats, and that’s one thing. Another thing is that the demand for meat is growing pretty dramatically. You know, we’ve heard about that trend in the U.S., but globally, we’ve seen a doubling of global population in 50 years, and in that same timeframe, a tripling of meat demand, right? So, you know, as emerging economies come online, and, you know, wealth emerges in populations all over the world, there’s a greater demand for a Western diet and a meat- centric diet. And so the question of how we address that, how do we address this huge growth in meat demand, as we add in all this new population in the next three decades is a big one and it’s probably the biggest one.

SREENIVASAN: You went to the largest salmon farm in the world. Is it Norway?

LITTLE: In Norway.

SREENIVASAN: So why are we going to find aquaculture and raising fish plus climate intensive?

LITTLE: The advantage of fish farming over livestock farming is pretty dramatic. The pound of salmon is about a pound of feed. The equivalent for chicken is two pounds of feed. For beef, it’s seven pounds of feed. So, the resources that go into the production of that protein are much higher. Part of that is just the sort of reality that livestock animals are defying gravity. They walk around on four legs. They are warm blooded, so it takes a lot more sort of caloric energy to keep them alive and moving. Fish are suspended in water. They’re cold blooded, so they just need less food to sort of grow and survive. But there’s a lot of concerns about what happens to a fish when you feed it corn rather than the wild fish that it would otherwise eat. Again, an effort to make it more sort of efficient to produce. How do you deal with the waste of the fish? So that’s what I explored in Norway.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. Going back — water is one of the key changes that we’re likely to see in this climate crisis. Right? So the aquaculture can’t happen without the water. I mean, the feed of the animals can happen, the crops can’t grow without the water. I mean, it’s it seems that you went through also in this book, well, how are we going to get access to clean water in the future?

LITTLE: So, about 70 percent but more than that, of the fresh water consumed by humans, goes to farms. It’s an amazing statistic, actually, you know. We can’t talk about the future of food and food security without talking about water. And I then went to Israel and explored desalination. The technology that essentially filters out salt from ocean water and you know, if we can drink brine, basically, that would be really, really great, because there’s a lot of it. It’s very energy intensive and cost intensive, but it’s beginning to happen.

There’s a $1.5 billion desalination plant that was installed a couple of years ago, in Carlsbad, California, to help bring, you know, a secure water supply in that region. Again, it is a story of economics. Water is getting more expensive in Southern California. So, it makes sense to spend all you know that money and energy in that region to do that. It led me then to recycled sewage, believe it or not, aka toilet to tap. These systems that essentially take, you know, recycle sewage water, and they put it through membranes, reverse osmosis membranes, that pull out all the contaminants and basically produce at the end, purified drinking water, that’s just as tasty as what you buy in a bottle in the grocery store.

SREENIVASAN: You drank it?

LITTLE: I drank it. You know, we think about global warming, and climate change pressures as sort of something that will affect our children and grandchildren. And that’s true. But the evidence of this sort of these trends are here, and so I was trying to link those stories together.

SREENIVASAN: You also had a chance to go see things that most of us aren’t going to right away, but vertical farms. Things that are being grown without any soil. You saw laboratories where they are dehydrating food. Of all of these different technologies, which ones look like they’re actually going to get to market pretty fast, and that we’re going to be interacting with our food that comes from these sort of new ways of thinking about it.

LITTLE: So, I think we should talk about two technologies for sure, and then maybe we get to some others. I write about these new — this emerging frontier of cell-based meats or lab meats, cultured meats, and that’s important getting back to that sort of discussion we were having about protein and how we will produce a sustainable supply of protein. But first, the progress that’s happening in the world of AI and robotics blew my mind. There was a company — there is a company called Blue River Technology. The CEO is Jorge Heraud. And he and his team developed the world’s first robotic weeder. And I saw the maiden voyage of this robotic weeder in Arkansas. It looked like this giant pest dispenser attached to the back of a tractor, and that the robot has been trained to identify and distinguish between the desirable — the crop that they would like to grow and the weed, and it emits with sniper-like precision, a tiny little jet of concentrated fertilizer, which is strong enough to incinerate a baby weed or herbicide on to just that plant, onto just that weed.

SREENIVASAN: So, it hits the weed without hitting the plant.

LITTLE: Hits the weed without hitting the plant, and this is an amazing departure from the current approach to you know, herbicides, which is broadcast. I mean, you see those images of airplanes dumping, you know, huge clouds of chemicals onto fields. And I should mention 90 percent reduction in herbicide application on the farms where these robots are — that these robots are weeding. And that if you apply that, if you move that beyond herbicides to fertilizers, you know, insecticides and so on —

SREENIVASAN: These are also huge costs for farmers.

LITTLE: Huge costs for farmers, right?

SREENIVASAN: Makes some economic difference.

LITTLE: Huge cost to the environment. So you do that smarter, you get chemicals out of the food system, and you begin to address all the climate impacts of that kind of farming, right. So that’s done — that’s bringing principles of sustainability to that system.

SREENIVASAN: So, in this equation, you’re kind of getting a third way here, which is that we’re using a high tech solution to a problem that people who want to take tech out of this equation would also agree with, who want to have less chemicals in the food, if you can figure out a robotic solution to put less chemicals in the ground and kill the weeds and get your plants growing, then both sides are kind of happier.

LITTLE: You’ve nailed it, you’ve totally nailed it. So, the thing is that there’s a lot of fear of technologies applied to food and with good reason because there has been so many examples of ways in which industrial agriculture and sort of tech heavy agriculture have diminished the quality of our foods, the nutritional density of our foods, brought on a lot of chemicals into the food we eat them. So, you know, it’s very reasonable, and I came into this research with a lot of concerns about that. I have little kids, and I want to be smart about do I give them GMO foods or not? Do I — should they eat only kale? Is it okay to do the mac and cheese? You know, a lot of those questions that we have, and I was really — I wanted to be sort of realistic about what should we fear? What should we not fear? You know, there’s a lot of concern and also excitement right now, in recent weeks about this emerging area of synthetic meats, or plant-based meets. The IPO of Beyond Meat has been spectacular and that’s a plant-based meat alternatives. And there’s a lot of billions and billions that are being funneled into — from the conventional media industry itself, and from Silicon Valley investors and others into these meat alternative products. We’ve heard about the Impossible Burger getting now picked up by Burger King and White Castle and Shake Shack, and it seemed improbable a couple of years ago, that mainstream fast food chains were going to pick this up. The veggie burger that bleeds was one of the headlines, but they have. And young consumers are driving this in part, but there’s a growing kind of concern about the impact of these foods and that’s really shifting markets. I looked at lab-based meats, which are, you know, a different beast altogether, quite literally. And it’s actual cells from animal muscle and tissues that are cultivated outside of the animal in what they call a bioreactor, which is basically like a very sophisticated crockpot. But the cells are given an environment where they can naturally replicate in a sort of solution, and they grow into masses of muscle mixed with fats and connective tissues, which is what we eat off of the animal and I ate a lump of bioreactor duck meat.

SREENIVASAN: Did it taste like duck?

LITTLE: It tasted like duck. Tasted very medium duck.

SREENIVASAN: And no duck was harmed in the creation of the meat.

LITTLE: And no duck was harmed in the creation of it. So, you know, this sounds weird, and sort of like the thing that we wouldn’t want to feed our children. On the other hand, the closer I looked at it, the less strange it was, honestly. And the more strange the existing system is, and that’s important. There’s so many flaws in meat production, in particular. And again, I’m complicit. I am a consumer of meat. But there are so many flaws and problems with that system. There are problems with the sanitation and contamination in the system. There are problems with the treatment of animals and there’s really big problems with the environmental impacts. So when you take all of that together, suddenly these things stop seeming so weird.

SREENIVASAN: The book is called “Fate of Food.” Amanda Little, thanks so much.

LITTLE: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

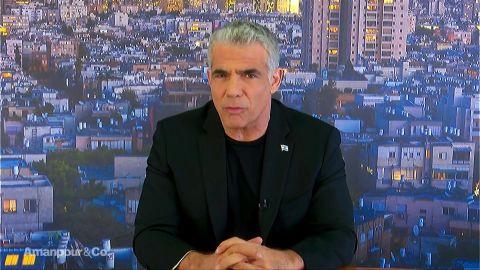

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Yair Lapid about the future of Israeli politics. Dina Nayeri joins the program to discuss the “Send Her Back” chants at a Trump rally in North Carolina. Hari Sreenivasan sits down with Amanda Little to discuss her new book, “The Fate of Food: What We’ll Eat in a Bigger, Hotter, Smarter World.”

LEARN MORE