Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You’re going to break the record of Ben-Gurion to be the longest termed prime minister of Israel, is that so?

BENJAMIN NETANYAHU, ISRAEL PRIME MINISTER: Who’s counting?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

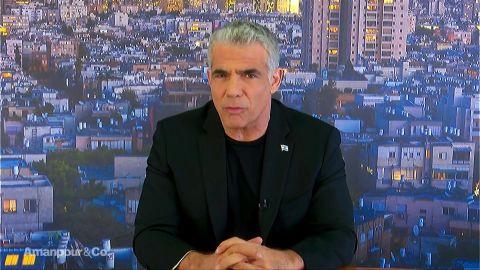

AMANPOUR: Bruised but determined, Benjamin Netanyahu becomes Israel’s longest-serving prime minister while forced to go for new elections. I speak to Yair Lapid, one of the main players in a Centrist coalition threatening to knock King Bibi of his throne. Then, race bating and identity politics. Author Dina Nayeri tells me about gratitude, the type refugees are expected to demonstrate for their place in America. And later.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANDA LITTLE: Climate change is becoming something we can taste.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Food for thought. Professor Amanda Little examines how we’ll feed our growing population when climate change starts to kill off crops. Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London. This weekend, Benjamin Bibi Netanyahu becomes Israel’s longest-serving prime minister since its first leader David Ben-Gurion. But that milestone comes while he’s under a cloud facing a string of indictment on corruption charges and forced him to fresh elections after failing to form a government in April. It’s turmoil at a time when Israel’s place in the world is changing fast, moving closer to its Arab neighbors as they find common cause against Iran. Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s peace plan is all but dead on arrival. As co-leader and co-founder of the Centrist Blue and White party, a coalition that won as many sits as Netanyahu’s Likud Party, Yair Lapid could be instrumental in ending the reign of King Bibi. If that happens, he’ll likely become Israel’s next foreign minister and find himself navigating a growing list of complex strategic challenges. And he’s joining me now from Tel Aviv. Yair Lapid, welcome to the program.

YAIR LAPID, FORMER ISRAEL FINANCE MINISTER: Thank you, Christiane. It’s been a while.

AMANPOUR: It has been a while. And actually, in the last seven or so weeks, you got a huge amount going on, you had an election in April and

now, you’re faced into another election. As I said, you know, you, your Centrist team won the same amount of seats. What do you think has changed,

if anything, to give you any confidence of doing anything better the next time around in September?

LAPID: Well, politics and confidence doesn’t often come together. But we feel good about our chances, mainly due to the fact that Netanyahu ran on

the election three months ago, a couple of months ago, telling everybody that the main thing is policy and politics and he’s not going to demand

immunity from his future partners.

And then he went into negotiating a new government and the only thing he’s been asking for was immunity. And the voters were disappointed and angry,

his voters. And I think they are still disappointed and angry because this is not a platform to run on in a country as complicated and that faces as

many challenges as Israel.

So, I think there is a change — there’s a shift in the way the Likud voters, his voters are looking at him, and for our votes as even — became

even more determined to — that it’s time for a change. So, yes, I think we have a fair chance of changing the government in September the 17.

AMANPOUR: So, we’ve seen over the last — I mean, we’ve said, he’s now, this weekend, becoming the longest serving prime minister since the great

Ben-Gurion and we’ve seen that he’s a survivor, he’s a wiley and canny political operative and he, you know, as I said, has many, many tricks up

his sleeve to win often.

When you say immunity, let’s just be clear about what you’re talking about, he is trying to get his partners to guarantee that what, that they won’t

allow the attorney general to indict him? I mean, the attorney general seems to be deciding and weighing up whether in fact do that, but that

would come after an election anyway.

LAPID: Yes. Well, you’re putting me in a corner here, which is what you do, and it’s fine. Because, you know, from previous talks we had, I made

it into a rule not to attack the prime minister in foreign press. So, I will just say the following. Netanyahu is looking for an immunity bill,

especially immunity bill which will make it almost impossible to indict him.

This is, of course, stands against the basic democratic rule of everybody is equal in face of the law. So, we were very much against it.

We’ve demonstrated against it. And unfortunately, it didn’t happen because he couldn’t form a government. And I think there is the possibility now

it’s too late because his hearing and then the indictment is coming in October, whatever the results will be.

You know what, you said this became the longest serving prime minister across the Ben-Gurion line. I’m not sure this is an achievement. I mean,

being a survivor in politics is a good thing, but it’s not an achievement in terms of running a country. And it made me think quite often about the

term limit in the United States, which seems like a better and better idea and this is one of the bills we are going to push here because I think we

have to have a term limit.

Because all this — the fact that we are dealing now with immunity and corruption and indictment is due to the fact that you cannot have a prime

minister that has been there for so long without something bad happening to the people around him and to himself. He’s just been there too long.

AMANPOUR: Well, look, let me pick up on a couple of points. One is that you think and said that you feel his own voters are getting disappointed

and you feel like your voters, the Centrists, because you’re a Centrists party along with Benny Gantz, are getting more energized.

But isn’t it the fact that actually the voters in Israel have been getting more and more conservative, have been moving more and more to a more

hardline right-wing position than in the past? I mean, that’s what you’re up against even with or without, whether Netanyahu is indicted or not.

LAPID: Yes. This is why the political fight or conundrum in Israel is no longer between the right and left but between the right and center. It’s

not something that is happening only in Israel, it’s happening all over the world that the left is struggling. Part of the famous pendulum rule.

So, what we are telling the Israeli voters is that this is not progressive versus conservative, this is not right versus left. This is Centrist.

We’re telling you, it’s time to look at the major issues of Israel. The Palestinian front, security, economics, the possibility of the world

recession, and just look for practical solutions to practical problems or pragmatic solutions to pragmatic problems.

So — and I think this is going very well within the Israel Republic to understand that these words, right and left, has become hollow in the past

few years. You know, it’s interesting. You’re saying the Israel Republic is becoming more and more conservative, but if you poll them, still around

70 percent of the Israelis will tell you they are for the two-state solution, which is not considered a conservative solution.

So, there is a gap here between the way they define themselves and the real way they look at the country’s problem.

AMANPOUR: Well, you know, that’s really interesting because one of the things that Netanyahu has been able to translate into winning is security,

and he stands for that and he claims he stands for that, and also, the economy. Your economy is doing very well and he has overseen that success

of the economy.

So, how do you position yourself, you know, to sort of tell the Israeli people who you’re trying to get to vote for you that it’s time for a

change? Why?

LAPID: Well, first of all, this is the first time in many, many years that we have a winning answer to the security question because both Benny Gantz,

Gabi Ashkenazi, my colleagues, Benny Gantz and Gabi Ashkenazi and Moshe Ya’alon, the three of them are four-star generals, former commander in

chief of the Israeli — the idea of the Israeli defense forces. Meaning, they are the people who made Israel as strong as it is. And they can —

they are the only people, maybe in the country, who can tell — look Netanyahu in the eye and say, “We understand more about security than you

and we know how to run the Israel security.”

The other thing is that after the election, the real numbers of the Israeli economy were released and we are actually facing a deficit that is way

higher than we thought. And — which means we are moving into sort of a storm. And I think the people of Israel remember that the last

time we face such a deficit — you know what, I know it’s boring for American audience to talk about deficit in other countries.

You have your own problems. But the last person who have solved a problem of that magnitude in terms of deficit in Israel was me in 2013 in which we

were able to help the country out of an almost economical crisis. So, they know I know how to deal with it and they know Benny Gantz and Gabi

Ashkenazi and Moshe Ya’alon know how to deal with security.

So, we have not good answers to Netanyahu but better answers for the Israeli people.

AMANPOUR: Can I just ask you very briefly, how much you feel you yourself have been tarnished? You just brought up the fact that you were a finance

minister in Netanyahu’s government. I mean, you say that you were reluctantly pushed into this position. But, you know, how much do you feel

that you are “tarnished” by having taken that position?

LAPID: I do not. I mean, when I — I came into politics, as you know, after being in television and being mostly a writer all my life. So — and

I came into politics — I know it’s the worst cliche and being a former writer I’m hesitant about cliches. But I didn’t come into politics because

I have three children. One of them with special needs and I felt the country is not doing very well about the future of those children.

And therefore, I feel obliged to take the responsibility and deal with the real problems, not to hide away from difficult spots. So, yes, it was a

difficult spot to become the finance minister during a crisis and have to take all of the tough decision I did in order to make sure Israel’s economy

stay as robust and advance as it is. But I feel, on the long run, it is becoming an advantage because people say, you know, “We want to have

leaders who are dealing with — who are not running away from responsibility or not running away from the tough moment, certainly like

Israel.”

AMANPOUR: OK. So, a very tough moment. Yair Lapid, a very tough moment and huge responsibility is to try to create peace in your land between you,

the Israelis and the Palestinians.

Now, President Trump and his key adviser and son-in-law, Jared Kushner, have revealed and gathered around the first part of their peace plan, which

was an economic peace plan. I want to know what you think about it. We know Israel didn’t go to the Bahrain conference nor did the Palestinian

authority. This is what the Palestinian Prime Minister, Mohammad Shtayyeh, told me about the process.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MOHAMMAD SHTAYYEH, PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY PRIME MINISTER: So, the issue here is not economic problems. The issue here is 100 percent political

that has to do with the fact that the Palestinian people are living under direct settler colonial regime, that’s called the settler colonial regime

of the State of Israel. In order for the Palestinians to live in a prosperous situation, we need to be independent.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Do you agree with him? I mean, he says the Trump administration is waging economic warfare. Do you feel that there needs to be a political

movement and not just economic?

LAPID: Well, first of all, let me remind you that even under administrations like the Clinton administration or the Bush administration

in which they offer the Palestinian the work, independence, more than 90 percent of the territory, self-recognition, they always said no. They are

just saying no to everything because they think it’s a zero-sum game and they want to get everything and negotiate nothing. This is — and they

have chosen resentment over the good of their own people.

And as we do this for 70 years, not for, I don’t know two years. The basic idea of telling young Palestinians there is a future for you, there is an

economical future for you, there are incentives, why don’t you go to your stubborn leaders and tell, “It’s time to listen.” I think it’s a good

idea. A lot of people said you cannot have only an economic plan resolve the political plan. I agree.

But to start by telling young Palestinians, “Don’t you understand that you your own leadership is preventing you from having a life,” is maybe an

original way of pushing forward a solution. Now, we have to have the over part of this, which is the political side of the plan. We don’t know what

the political side of the plan. They postponed it again for after the election.

I believe that we need to separate from the Palestinians. I believe the Palestinians have the right for self-recognition. But we have to remember

one very important thing. I acknowledge the fact that the Palestinians are suffering but they are not suffering because of Israelis,

they are suffering because of other Palestinians who made them suffer.

And anyone who comes up with an idea how to push forward for young Palestinians to understand they’re going to have a future only under an

agreement, I think it’s a good idea and we should try and at least seriously look into it, findings ways to move forward.

AMANPOUR: Maybe Israel will choose to unblock their revenues, their tax revenues, all the things that you’re meant to be sending them that you are

not sending right now, and that will make a big difference. Can I just quickly switch to U.S/Israel relations? Let me just — I need to — no,

no. I need to move on. I need to move on. I need to move on.

LAPID: OK. Go on. Sure.

AMANPOUR: There’s a very controversial statement by a member of the cabinet, Rafi Peretz, current education minister, who has compared

intermarriage among American Jews. He’s called it a second holocaust because of how it limits the Jewish population growtn and he’s been

criticized by the Anti-Defamation League in the United States and even by other members of the Israeli cabinet. I mean, does that kind of

terminology have any place in Israel politics today?

LAPID: You remember I told you I usually don’t criticize the government on foreign press, I’m going to criticize the government on foreign press.

This is stupidity, this is racism, this is something that cannot be said by anyone. I mean, this — my understand of a holocaust survivor, this is no

second holocaust. The people — the reform and conservative (INAUDIBLE) in the United States are our brothers and sisters. This is a legitimate form

of Judaism.

And even if somebody is marrying a non-Jew, we — some people say it might — it is sad. It is not a second holocaust. This is something the prime

minister should have taken aside and firing on the spot. If not for this then for what he said later on that he’s also against gay marriage and

later on also for apartheid.

This is the kind — but let me just assure you, the one thing I had to say that is a bit comforting is that he is not representing a lot of people.

This is a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of Israelis. We all have our fair share of people who are racist and, of course, it angers us all.

But this is not what the majority — the mass majority of Israeli think and I think its disastrous and horrific say.

AMANPOUR: Let me ask you because there’s a lot of controversial and some are now saying racist commentary from the President of the United States.

You think Israel is a bit of a political football. You’re well away that there is a war going on between the president and four U.S. congresswomen

of color who are Americans. And he is accusing one or more of them of being anti-Israel. In other words, Israel is being used as a political

football in this fight. How do you feel about that?

LAPID: Well, is there anything in the conversation so far that made you feel that we don’t have enough problems of our own so we will interfere

with American politics? I’m, of course, following this. And, of course, I don’t like the fact that Israel is becoming a subject that is not

bipartisan in the United States. I think Israel always was privileged to have a bipartisan statue and I think it should stay this way. And — but I

will not get into American politics. It’s — we have our own problems, I guess.

AMANPOUR: And on that note, Yair Lapid, thank you very much indeed for joining me from Tel Aviv. Thanks very much.

Now, for President Trump, Israel is a useful prop in what fast becoming race bating reelection tactics. Congresswoman Ilhan Omar who came to

America as a refugee from Somalia is among four congresswomen who are his latest targets, as we’ve just been saying. Listen to this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DONALD TRUMP, U.S. PRESIDENT: In case you have somebody that comes from Somalia, which is a failed government, a failed state, who left Somalia,

who ultimately came here and now is a congresswoman who is never happy says horrible things about Israel, hates Israel, hates Jews, hates Jews.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: At a Trump rally in Greenville, North Carolina last night, a chant of “Send her back” became this years’ answer to “Lock her up.” My

next guest, Dina Nayeri, is all too familiar with this language and how fear and privilege are used to create an us versus them

narrative.

The Iranian born novelist came to America as a young girl seeking asylum from persecution back home. Her new Book, “The Ungrateful Refugee,”

challenges us to assess the expectations and prejudices places on refugees around the world. And she’s joining me here now.

Welcome to the program.

DINA NAYERI, AUTHOR, “THE UNGRATEFUL REFUGEE”: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: You know what, I couldn’t help but be struck that the title of the book is so appropriate to the conversation that’s being had in the

political field in American right now. So, “The Ungrateful Refugee” is almost like President Trump is saying that these — certainly, Ilhan Omar

who came as a refugee is ungrateful, and adding that to the — you know, to the other four who were born and bred in the United States.

NAYERI: Absolutely. Everything he is saying implies that. I mean, he implies that, you know, because she came here from another country, because

she was given opportunities, she should be silenced against everything that, you know, America does. So, she should be grateful. She shouldn’t

participate in the way a native-born American or a neighbor American would participate, and I think that’s absurd.

AMANPOUR: Can I just play this little clip from President Trump?

NAYERI: Sure.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TRUMP: If you’re not happy here, then you could leave. As far as I’m concerned, if you hate our country, if you’re not happy here, you can

leave. And that’s what I say all the time.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: But nobody said they weren’t happy here. What do you think is going on? And I’m going to get to your book and the title of it. What do

you think is happening here?

NAYERI: Well, what’s happening is he’s trying to separate, you know, people who, you know, came from somewhere else, from native Americans,

native-born Americans. What he wants to do is say that, you know, “You don’t have as much of a right to talk about the issues, to be a part of the

political process, you know, and to be a part of our country. So, you should be second-class citizens. Always quiet, bow and grateful.”

And I think it plays to his base. I mean, the term ungrateful refugee is not new. It’s — I’ve heard it when I was a child. When I was a child,

you know, people told me all the time, you know, “Oh, you must be so grateful or, you know, of course, why don’t you go back where you came from

when,” when they were angry.

AMANPOUR: Did you have a lot of that? I mean, I wanted to get to your book because, you know, it is called “The Ungrateful Refugee.” And I kind

of wanted to ask you, you said it’s not new, but where did it come from in your experience? You left Iran as a kid.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: To escape the Islamic revolution. Your mother was —

NAYERI: And the war.

AMANPOUR: — a Christian. And the war with Iraq, exactly. And there was persecution against her.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: She was a doctor then. Just describe a little your exodus, if you like, and your arrival in America.

NAYERI: So, we escaped to Dubai. My mom was in a lot of trouble with the Islamic Republic and we went to Dubai. We were there as undocumented

immigrants for, you know, 10 months and then we became refugees. We were sent to a refugee camp in Italy and stayed there for six months before we

were given asylum in America and sent to Oklahoma.

AMANPOUR: What did you meet when you got to Oklahoma? What sort of reception?

NAYERI: Well, you know, it was interesting. It was different from what people are getting now in a couple of ways. You know, first of all, I

think there was a certain level of welcome because we were Christians and, you know, there was a certain sense of duty that as an American they had to

— or, you know, I suppose people had a duty to the world. You know, and we were some of the outcasts of the world and so, they had to take us in.

But on a personal level, there was definitely hostility. There was definitely a sense that, you know, we don’t quite belong here and that we

should participate in a different way than, you know, Americans do. We shouldn’t aspire toward leadership or any kind of greatness. You know, we

should just kind of be on a lower rung of society.

AMANPOUR: I was stuck by how you said that you landed in Oklahoma and it quickly became obvious to you that there hadn’t been a huge amount of

interface between the people who were your neighbors and people around the rest of the world. And you said that they — you used the term “ching-

chongese.”

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: A the way they talk to your mother. What’s all that to you?

NAYERI: To me, at school, I mean, I think — what’s interesting was that they didn’t even have much of a sense of the geography or what was going

on, you know, in the world. That they literally would ching-chong at me as a —

AMANPOUR: Meaning what, just thinking you were Chinese or Asian?

NAYERI: Yes. Exactly, exactly. And, of course, these were children, but all of this, you know, clearly came from somewhere and it was, you know, a

very isolated little town. It was before the age of the internet when people hat access to, you know, the goings-on in the world. And it was

just, you know, basically supposed to signal to me that I’m different and an outsider and I don’t belong there.

AMANPOUR: And you had your own sort of version of send her back or go back to where you came from.

NAYERI: Well, I mean, many things, certainly. I mean, people were always calling us names based on our, you know, place of origin. And I was

— I suppose I always just kind of felt like I had to do extra well, you know, in order to belong. I felt very much like, you know, to

really be American I had to be one of the best Americans. So, I became very obsessed with things like getting into Harvard and, you know, becoming

kind of an overachieving kid. I became obsessed with a Korean sport, taekwondo, so that I could actually, you know, try get into Harvard.

AMANPOUR: I want to ask you about that because that is one fascinating thing.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Listen, as we are here, we have a this just in moment.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: President Trump is saying that he is not happy with the “Send her back” chants. I mean, he can see that it’s really beyond —

NAYERI: But he didn’t say anything at the time.

AMANPOUR: But he is saying it now, apparently. Which is interesting and important that that gets stopped and that he stops it because it is very,

very ugly.

NAYERI: Good.

AMANPOUR: But — so, you were an overachiever.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You wanted to prove that you were a good refugee —

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — that you weren’t sort of, you know, an incubating terrorist. I mean, I know because I’m also an Iranian refugee, immigrant and I know

what its like to have to prove yourself, that you’re good, that you’re nice, that you —

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — can play.

NAYERI: And grateful.

AMANPOUR: And achieve and, you know, not frighten the natives, so to speak.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You got to Princeton and you got to Harvard and you have made your place in the world. But tell me about the taekwondo because that’s

how you got into Princeton.

NAYERI: Well, it was actually kind of this crazy scheme that happened to work because when I arrived in the U.S. I quickly realized that this was

not the America that I had been dreaming of. This was Oklahoma. It was very different from New York and L.A. and I decided I’m going to get myself

out of here. Maybe the Iran escape was mother’s escape. This will be my escape.

So, I studied. I did lots of, you know, academic work and I realized that’s not enough for Harvard. So, I said, “I’m going to win a national

championship in a sport,” and what is the sport with the fewest women and also, you know, a sport that hands out trophies by belt, by weight, by age,

by everything.

AMANPOUR: And that would differentiate your C.V.?

NAYERI: Exactly. Well, not only that, it would give me the highest chance of getting a national championship. So, three years I practiced. I got

into Korean culture. I started to enjoy it. And then I won a national championship and I got into Princeton. Funny enough, did not get into

Harvard.

AMANPOUR: You did later.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You went late as a post-grad, right?

NAYERI: I did.

AMANPOUR: Yes. So, I mean, here you are, a very accomplished person at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, which is one of the best, if not, the best in

the country. You’re a novelist. You’ve written this important book. And you’re a bit of an activist for the plight of refugees. We are at a moment

where the number of refugees around the world, I think it’s more than 70 million right now. It’s at an all-time high.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: It just keep surpassing all the records. And you’ve been to some of the camps around the world that are taking people from Syria and

Afghanistan and even Iran. What do you notice there? They’ve been looked after. They are being housed and fed, but?

NAYERI: Well, I think the thing that’s missing is someone looking out for their dignity. Because the thing that happens is, you know, in the camps,

people tend to focus on all of the tangible needs. So, for example, they focus on lack of food and shelter and all of that stuff. They don’t give

them much education or anything to do and they’re not allowed to work.

So, you know, what ends up happening is that people go into depressions and the waiting becomes this terrible burden. And waiting is such a bigger

burden really than anything, especially when you don’t know that it will end, it’s this abjection.

So, what I saw most was, you know, people just desperate to find out what their fate will be. I think — you know, there was one charity that I

found called “Refugee Support” that actually does this wonderful work of giving aid with dignity by putting grocery stores and, you know, giving out

the donated food that way with points. People can shop, again, with dignity. I think dignity and shame are two of the biggest things that —

AMANPOUR: I’m really interested about it because you write that accepting charity is an ugly business for the spirit.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And the person who founded or co-founded “Refugee Support,” Paul Hutchings, said, “Wouldn’t it be nice if we could give people food and

clothing without taking away their dignity. ”

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean, just expand on that a little. You have a little. But, I mean, even the kind of, I don’t know, comforts that they might find in a

container or in a tent —

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — that they go to, the kind of furniture at some — what is it that you think needs to happen?

NAYERI: Well, I mean — so, I think the biggest thing is really education. I think what Paul is doing is wonderful because I was in a camp in which

they threw piles of clothes in the parking lot and we were supposed to sift through them. And as — you know, my mother was a doctor in Iran and I was

an educated kid, I mean, I — we had some pride. We — to have the clothes just out there like that, it felt like a falling down in the world. And

even though this were the helpers.

But — so, I think what Paul is doing is really important. But the problem with the camps is that these people wait for so, so long, and

the children don’t have a place to go to school.

And the problem with that is that they actually don’t know when the waiting will end, so — and there’s turnover. So, it’s really hard to set up a

school, and I know there are charities that are trying to address this, but I think it’s one of the most important things.

If we’re going to make people wait, if we are going to exert that kind of power over them, we need to give them some basic human dignity, the ability

to work towards something, a purpose in life.

AMANPOUR: I just want to put up a picture of you when you were very little. This is your passport photo when you left Iran. Let’s have a

look. You’re there swathed in the hijab at that time and that’s a very official one.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean, that is —

NAYERI: With the stamp.

AMANPOUR: How old were you for heaven’s sake?

NAYERI: Oh, I was eight years old when we left.

AMANPOUR: And you had to have that for the passport?

NAYERI: Yes. And I had to have it starting at six when I went to school. I went to a very strict Islamic Republic School for Girls. And we were put

under the hijabs starting from when I was in the first grade.

We were taught by these very, you know, stern women in long black chadors and you know, there were chants. Every morning, there were chants, you

know, “Death to America, death to Israel,” you know, and it was frightening and it was scary.

And to be honest, you know, going back to the beginning, when I heard those chants, I was a little bit triggered, you know, because chanting for me

means something. It’s frightening, it means, you know that there are dangers that are very, very directly coming toward me.

And I imagine that every refugee in America feels that when they see that kind of footage, and they feel a little bit less welcome.

AMANPOUR: I mean, again, if President Trump can influence his followers, and he says he’s not happy about that, hopefully that will be nipped in the

bud like it should be right now.

NAYERI: Exactly. I’m really happy if —

AMANPOUR: But you say, you know, along these lines in your book, you write about your daughter, “Becoming a mother to a dark little girl with a

mischievous smile in the age of Brexit and Trump terrifies me. Whatever her gifts, she is going to get yourself into trouble in this hateful world

slowly coalescing around us.”

How are you going to explain all of this to your daughter? How are you going to navigate her through? Because let’s not forget, I mean, you live

here now, right?

NAYERI: Yes, I do.

AMANPOUR: And you yourself went through bullying and kind of some violence here when you first —

NAYERI: I had the tip of my finger cut out.

AMANPOUR: Here in England in the schoolyard?

NAYERI: Yes, I did. I did. It was very scary. I remember thinking of English school boys, all through my childhood. It’s just mean boys. And I

know they’re not, but they’re the ones who chopped off the tip of my finger, and so it stayed with me.

But I think what I want to teach Elena first, before I tell her about all these stories of the world and what’s happening and where she belongs in

it, I want to teach her about joy and the joys that comes from different cultures. I want to teach her songs from Iran, songs from France where her

father’s family is from. You know, the food and all of that. And I think that’s important. That’s really the key.

AMANPOUR: So, tell me actually a little bit about that. Because, you know, if you go to France, or you come to England, or you go to the United

States, there is so much diversity of culture, whether it’s Middle Eastern, or Chinese or Indian, or whatever it might be, and food and culture is

huge.

NAYERI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: So those societies are open to this kind of, you know, cultural diversity. I mean, does your daughter see that? Or is it —

NAYERI: She will see cultural diversity. Oh, of course, I think she does. I mean, she certainly has started to talk about color. You know, she asks

about people in nursery, you know, why is this person darker than that person?

And, you know, we welcome those kind of questions. We want to tell her that everybody is the same. You know, and everybody has gifts that go way

beyond what you can see physically and at three, all she can see is the physical.

And I think this is just so important to talk at that age to them. I wish that the kids in Oklahoma had had their parents say to them that there’s a

big huge world out there full of people with, you know, all kinds of different stories.

AMANPOUR: And just to follow on and lastly, to bring it back to the taekwondo, you have said, “It is a perfect sport for teenage girls,” and

yet they were almost none in this dojang that you were in. “I loved winning at a male sport. I was still angry about so many things — the

hijab, the Islamic Republic, the fat old church man who made high school football players feel like gods while they shame women who dared to want

too much.”

So, it is something that’s very empowering for young girls. You must have felt as a girl super empowered by achieving this martial art.

NAYERI: Absolutely. Gosh, I can’t tell you what I felt the first time I stepped into that dojang and was told to hit that bag. I had so much anger

and so much exhaustion and so much fear.

You know, we had escaped from Iran. The Islamic Republic had been brutal. Those refugee years had been brutal. We had fallen in social class, we had

nothing. And I had this goal, this goal of getting into Harvard and it was so far away and when I could go into this studio and have you know, this

this big, strong man, hold the bag and tell me to just hit, hit, and hit, and hit until I’m done. It felt good.

NAYERI: And it made me a calmer person, ironically. And it made me more confident, and I’m absolutely going to give that to my

daughter, every girl should do martial arts.

AMANPOUR: So, there you go. On that note, Dina Nayeri, thank you so much indeed for joining me.

NAYERI: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: Now, for those forced to flee home, the search for belonging can take a lifetime with the sights and smells and tastes of home left behind.

And as we said, the number of global refugees has hit an all-time high. Severe food shortages, a byproduct of climate crisis displaces millions of

starving people around the world.

Now, as Amanda Little tells in her new book, “The Fate of Food,” our heating planet is drastically changing the way we break bread, from cloned

cows to edible insects, our Hari Sreenivasan checks out what may be on the menu of the future.

HARI SREENIVASAN, PBS NEWSHOUR HOST: So lay out the problem in case for us. Where are we headed with global food supply and demand?

AMANDA LITTLE, AUTHOR, THE FATE OF FOOD: So the central paradox of our food future is essentially that we’re seeing huge increases in population.

We’ve heard 9.5 to 10 billion by mid-century. And at the same time, pretty significant threats to global food supply.

So the International Panel on Climate Change predicts that we’ll see, I think it’s two to six percent decline in crop production every decade going

forward because of different climate change pressures.

And they range pretty dramatically from drought and heat to flooding to shifting seasons confusing the plants to invasive insects. And that sort

of contradiction, right, of increasing demand, decreasing supply, poses this really interesting challenge to farmers, as well, as engineers, and

all of these other folks that are sort of joining this effort to address food security.

SREENIVASAN: This book isn’t necessarily a pessimistic look. You’re actually spending a fair amount of time looking at ways that we’re trying

to solve this, and some of them which are scalable.

LITTLE: Yes, this is interesting. A lot of the response has been this book is really optimistic. And that’s been a bit surprising to me, because

it, it felt like very hard earned optimism. And I am very interested in the way in which sort of our survival instinct is kicking in and we’re

beginning to see that platonic maxim, “Necessity is the mother of invention,” right?

The pressures to evolve and adapt, in this sort of — to these new realities, are certainly driving really exciting innovation. And so

chapter by chapter, I explore things happening that are very new — radically new in areas like artificial intelligence and robotics, CRISPR,

and gene editing, vertical farms, and so on.

And also some really old ideas like permaculture and edible insects and ancient plants. And so, you know, it’s not all just tech will save the

day. But it’s more how can we blend sort of strategies that are both traditional farming practices, and also these radically new approaches that

are coming online.

SREENIVASAN: You can break the book or the structure down into three or four big parts, and we’ll try to go through those. First, let’s take a

look at kind of plants and crops. You start out in chapters where you’re talking to an apple farmer in Wisconsin, and you’re seeing the real effects

that are happening on his land now —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDY FERGUSON, FARMER: It takes a special kind of person to grow apples. You’ve got to be able to roll with the punches that Mother Nature throws at

you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

LITTLE: It was important for me to start out this book in an apple farm in Wisconsin. I traveled to a dozen countries and probably 15 states, and you

know, I was excited to tell some of these far-flung stories, but I wanted it to begin sort of, you know, at home, really, and I heard about farmers

growing apples and cherries and peaches and citrus all over the country dealing with these– what they call total kill events — which is early

blooming in these orchards because of warmer winters.

And then a normal freeze comes along and April or May, and kills off these mature blooms and emerging fruits.

SREENIVASAN: The trees are confused because it’s so warm, they decide, oh, this must be spring and they blossom and they lose all that protection from

the winter.

LITTLE: That’s right. But you know, what I learned from Andy Ferguson, who is this young farmer, you know, he was saying that the risks that I

have to mitigate, you know, are far greater. He is actually separating the land that he farms, so, that if there’s an extreme weather event in one

region, he knows that the apples he is growing in another region might not have had that hailstorm or a total freeze, a freeze event.

SREENIVASAN: He is not putting all those apples in one basket.

LITTLE: Right, not putting all those apples in one basket. Exactly. And that was the beginning of this broader story was, what are these impacts

first of all? And what are the ways that are, you know, sort of obvious, and also very subtle and unexpected that climate change is beginning to

affect our food system.

And along the way, as I ate Andy’s apples or traveled to a tiny corn farm in Kenya, or to a giant fish farm in Norway, I began to sort of get this

recurring kind of message that climate change is becoming as something we can taste.

It’s an issue that for so many of us feel so far flung that we associate with melting ice caps and polar bears, and it is that. But it’s also

beginning to sort of affect us in these very intimate ways. And it’s becoming in that sense a kind of kitchen table issue, you know.

SREENIVASAN: And it’s not just anecdotal from Andy’s life, you’re actually pointing to a different research that’s being done, and has been done going

back through records as far as they’ve been kept. And you can see the change in volatility of the weather and how crazy the freeze events are,

how much more frequent they are.

I mean, Andy’s life as a farmer has been affected and is continuing to be so.

LITTLE: It’s such an important point. You know, at a time when we have politicians making decisions and essentially launching an assault on

climate science, there’s so much research that’s coming up.

As you know, one of the scientists I interviewed at, I think it’s University of Michigan told me, the data is telling a story. You know,

another scientist said to me, we have one horticultural blood on our hands. You know, these plants are telling us a story, and they’re telling us a

story of sort of chaos and confusion and real trends that we can track over time through the story of food.

SREENIVASAN: As more people come online, they don’t automatically just become vegetarians. They also want protein in their diets, and meat

consumption is probably one of the most ecologically intensive things, energy-wise that we have on the planet and that’s — what you start

pointing out is there’s more effect that we have through meat consumption on climate change than we do from driving or flying.

LITTLE: This is an important transition from — and we’re talking about crops and vegetable and grain production to proteins. And there’s a very

intimate connection. More than a third of all the grains produced goes to livestock production, right?

So, what happens is, the changes that are affecting our fields is also affecting the farmers who are raising our meats, and that’s one thing.

Another thing is that the demand for meat is growing pretty dramatically.

You know, we’ve heard about that trend in the U.S., but globally, we’ve seen a doubling of global population in 50 years, and in that same

timeframe, a tripling of meat demand, right? So, you know, as emerging economies come online, and, you know, wealth emerges in populations all

over the world, there’s a greater demand for a Western diet and a meat- centric diet.

And so the question of how we address that, how do we address this huge growth in meat demand, as we add in all this new population in the next

three decades is a big one and it’s probably the biggest one.

SREENIVASAN: You went to the largest salmon farm in the world. Is it Norway?

LITTLE: In Norway.

SREENIVASAN: So why are we going to find aquaculture and raising fish plus climate intensive?

LITTLE: The advantage of fish farming over livestock farming is pretty dramatic. The pound of salmon is about a pound of feed. The equivalent

for chicken is two pounds of feed. For beef, it’s seven pounds of feed.

So, the resources that go into the production of that protein are much higher. Part of that is just the sort of reality that livestock animals

are defying gravity. They walk around on four legs. They are warm blooded, so it takes a lot more sort of caloric energy to keep them alive

and moving.

Fish are suspended in water. They’re cold blooded, so they just need less food to sort of grow and survive. But there’s a lot of concerns about what

happens to a fish when you feed it corn rather than the wild fish that it would otherwise eat. Again, an effort to make it more sort of efficient to

produce. How do you deal with the waste of the fish? So that’s what I explored in Norway.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. Going back — water is one of the key changes that we’re likely to see in this climate crisis. Right? So the aquaculture

can’t happen without the water. I mean, the feed of the animals can happen, the crops can’t grow without the water. I mean, it’s it seems that

you went through also in this book, well, how are we going to get access to clean water in the future?

LITTLE: So, about 70 percent but more than that, of the fresh water consumed by humans, goes to farms. It’s an amazing statistic,

actually, you know. We can’t talk about the future of food and food security without talking about water.

And I then went to Israel and explored desalination. The technology that essentially filters out salt from ocean water and you know, if we can drink

brine, basically, that would be really, really great, because there’s a lot of it. It’s very energy intensive and cost intensive, but it’s beginning

to happen.

There’s a $1.5 billion desalination plant that was installed a couple of years ago, in Carlsbad, California, to help bring, you know, a secure water

supply in that region.

Again, it is a story of economics. Water is getting more expensive in Southern California. So, it makes sense to spend all you know that money

and energy in that region to do that.

It led me then to recycled sewage, believe it or not, aka toilet to tap. These systems that essentially take, you know, recycle sewage water, and

they put it through membranes, reverse osmosis membranes, that pull out all the contaminants and basically produce at the end, purified drinking water,

that’s just as tasty as what you buy in a bottle in the grocery store.

SREENIVASAN: You drank it?

LITTLE: I drank it. You know, we think about global warming, and climate change pressures as sort of something that will affect our children and

grandchildren. And that’s true. But the evidence of this sort of these trends are here, and so I was trying to link those stories together.

SREENIVASAN: You also had a chance to go see things that most of us aren’t going to right away, but vertical farms. Things that are being grown

without any soil. You saw laboratories where they are dehydrating food. Of all of these different technologies, which ones look like they’re

actually going to get to market pretty fast, and that we’re going to be interacting with our food that comes from these sort of new ways of

thinking about it.

LITTLE: So, I think we should talk about two technologies for sure, and then maybe we get to some others. I write about these new — this emerging

frontier of cell-based meats or lab meats, cultured meats, and that’s important getting back to that sort of discussion we were having about

protein and how we will produce a sustainable supply of protein.

But first, the progress that’s happening in the world of AI and robotics blew my mind. There was a company — there is a company called Blue River

Technology. The CEO is Jorge Heraud. And he and his team developed the world’s first robotic weeder. And I saw the maiden voyage of this robotic

weeder in Arkansas.

It looked like this giant pest dispenser attached to the back of a tractor, and that the robot has been trained to identify and distinguish between the

desirable — the crop that they would like to grow and the weed, and it emits with sniper-like precision, a tiny little jet of concentrated

fertilizer, which is strong enough to incinerate a baby weed or herbicide on to just that plant, onto just that weed.

SREENIVASAN: So, it hits the weed without hitting the plant.

LITTLE: Hits the weed without hitting the plant, and this is an amazing departure from the current approach to you know, herbicides, which is

broadcast. I mean, you see those images of airplanes dumping, you know, huge clouds of chemicals onto fields. And I should mention 90 percent

reduction in herbicide application on the farms where these robots are — that these robots are weeding.

And that if you apply that, if you move that beyond herbicides to fertilizers, you know, insecticides and so on —

SREENIVASAN: These are also huge costs for farmers.

LITTLE: Huge costs for farmers, right?

SREENIVASAN: Makes some economic difference.

LITTLE: Huge cost to the environment. So you do that smarter, you get chemicals out of the food system, and you begin to address all the climate

impacts of that kind of farming, right. So that’s done — that’s bringing principles of sustainability to that system.

SREENIVASAN: So, in this equation, you’re kind of getting a third way here, which is that we’re using a high tech solution to a problem that

people who want to take tech out of this equation would also agree with, who want to have less chemicals in the food, if you can figure out a

robotic solution to put less chemicals in the ground and kill the weeds and get your plants growing, then both sides are kind of happier.

LITTLE: You’ve nailed it, you’ve totally nailed it. So, the thing is that there’s a lot of fear of technologies applied to food and

with good reason because there has been so many examples of ways in which industrial agriculture and sort of tech heavy agriculture have diminished

the quality of our foods, the nutritional density of our foods, brought on a lot of chemicals into the food we eat them.

So, you know, it’s very reasonable, and I came into this research with a lot of concerns about that. I have little kids, and I want to be smart

about do I give them GMO foods or not? Do I — should they eat only kale? Is it okay to do the mac and cheese? You know, a lot of those questions

that we have, and I was really — I wanted to be sort of realistic about what should we fear? What should we not fear?

You know, there’s a lot of concern and also excitement right now, in recent weeks about this emerging area of synthetic meats, or plant-based meets.

The IPO of Beyond Meat has been spectacular and that’s a plant-based meat alternatives.

And there’s a lot of billions and billions that are being funneled into — from the conventional media industry itself, and from Silicon Valley

investors and others into these meat alternative products. We’ve heard about the Impossible Burger getting now picked up by Burger King and White

Castle and Shake Shack, and it seemed improbable a couple of years ago, that mainstream fast food chains were going to pick this up. The veggie

burger that bleeds was one of the headlines, but they have.

And young consumers are driving this in part, but there’s a growing kind of concern about the impact of these foods and that’s really shifting markets.

I looked at lab-based meats, which are, you know, a different beast altogether, quite literally. And it’s actual cells from animal muscle and

tissues that are cultivated outside of the animal in what they call a bioreactor, which is basically like a very sophisticated crockpot.

But the cells are given an environment where they can naturally replicate in a sort of solution, and they grow into masses of muscle mixed with fats

and connective tissues, which is what we eat off of the animal and I ate a lump of bioreactor duck meat.

SREENIVASAN: Did it taste like duck?

LITTLE: It tasted like duck. Tasted very medium duck.

SREENIVASAN: And no duck was harmed in the creation of the meat.

LITTLE: And no duck was harmed in the creation of it. So, you know, this sounds weird, and sort of like the thing that we wouldn’t want to feed our

children. On the other hand, the closer I looked at it, the less strange it was, honestly. And the more strange the existing system is, and that’s

important.

There’s so many flaws in meat production, in particular. And again, I’m complicit. I am a consumer of meat. But there are so many flaws and

problems with that system. There are problems with the sanitation and contamination in the system. There are problems with the treatment of

animals and there’s really big problems with the environmental impacts.

So when you take all of that together, suddenly these things stop seeming so weird.

SREENIVASAN: The book is called “Fate of Food.” Amanda Little, thanks so much.

LITTLE: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So, the race is on to figure out how to feed a growing global population sustainably as food production declines. Join me tomorrow as we

dedicate our show to the 50th Anniversary of the moon landing.

I’ll be speaking with one of the astronauts who took part in the mission that changed the course of human history. Here is President Nixon calling

Apollo 11 when the news first came in in 1969.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Go ahead, Mr. President. This is Houston now.

RICHARD NIXON, FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES: Hello, Neil and Buzz. I’m talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White

House, and this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made from the White House. I just can’t tell you how proud we all are of

what you have done.

For every American this has to be the proudest day of our lives.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And still the most inspirational.

That’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow.