Read Transcript EXPAND

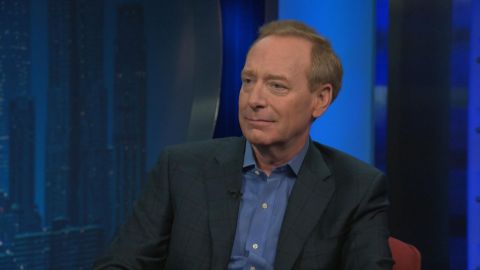

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And now, we separate the fact from the science fiction with our next guest, Brad Smith. As president of Microsoft, he leads one of the world’s most valuable companies. His new book pulls back the curtain on Microsoft as the company grapples with the ethical questions that come with technology like artificial intelligence. Coauthored with Carol-Ann Brown, it’s called “Tools and Weapons.” And he sat down with our Hari Sreenivasan to talk about the promise and the peril of the digital age and why he’s one of the few tech leaders today calling for more, not less, privacy regulation.

HARI SREENIVASAN, CONTRIBUTOR: Early on in your book, I’m just going to read a quick paragraph. When you’re describing a data center that you walk into, you say somewhere in one of these rooms, in one of these buildings, there are data files that belong to you. They have the e-mail you wrote this morning, the document you worked on last night, and the photo you took yesterday afternoon. They also, likely contain personal information from your bank, doctor, and employer. And you lead with that information belongs to me, but I don’t feel like I really have control over it. I mean, how do I find it, delete it once and for all, if it’s copied in all these different rooms that I have no access where they are.

BRAD SMITH, PRESIDENT, MICROSOFT: I think that is one of the great questions of our time. These huge data center campuses have become, in many ways, the most important piece of infrastructure of the 21st Century. Yet no one ever gets to go inside.

SREENIVASAN: Like Digital Fort Knox.

SMITH: Yes. And that’s why we start the book by taking people on a tour of a data center to see this. Because I think until you sort of grasp that physical reality, you can’t quite then get your mind around the security issues, the privacy issues, the broader technical issues that are just being unleashed.

SREENIVASAN: You know, there’s this old phrase that I remember from when I covered the tech industry, if you can’t see the product, you are the product, right? That they’re basically — the data about you and how you use these services is being bought and sold. So I’m wondering if I use Bing Search and if I have a Hot Mail account and if I use an Edge Browser, isn’t the default that advertisers have access to how I navigate the world and aren’t they figuring out all sorts of little bits of information about me?

SMITH: I don’t think every company is approaching this in the same way. I think the challenge is it’s hard to know, you know, what the different companies are doing. You know, in Microsoft, we focus more on, you know, really saying, hey, our business is not fundamentally advertising, it’s on protecting your data rather than trying to monetize it in that way. But I also think that this really turns on the protection of privacy more broadly. One reason we devoted a chapter on the development of consumer privacy issues is because we think this has been, you know, going through waves of evolution, starting in the 1990s. But we think we’re now approaching a third wave where we’re going to see more government rules in place because I think what the marketplace is telling us is that people do care about privacy but they don’t feel they can pull away from these services and instead they, in fact, want more government rules to protect them.

SREENIVASAN: Most tech companies have been, for a while, saying I don’t want any government interference in this. And they’ve really had that run up the place. And here you are saying I think there’s a happy medium here and we should go in that direction.

SMITH: I think we at Microsoft sometimes approach these issues from a somewhat different perspective in part because of our own historical experience. We went through this episode in the late 1990s when the U.S. government and states obtained a court order to break the company up. You know, we successfully defended against it but we learned we had to change. That we needed to connect with the world. We needed to assume more responsibility. And I think what that taught us, in part, is that when you think about a long-term vision, stability, success is served best by sustaining the publics’ trust. And you can’t expect the public to trust companies if that’s the only thing they’re allowed to trust. The public does depend on laws and controls and a fabric that supports the community as a whole. And so we do think that a broader perspective, if you will, is a more enlightened one.

SREENIVASAN: So as a software and services company, how does Microsoft’s operation differ from Google or Facebook who make their money from advertisers?

SMITH: If you look at where most of Microsoft’s revenue comes from, it is basically persuading you to pay us to use our software or devices, you know, in our software as a service. And then, yes, I would say part of our value proposition is you’re paying us to keep you secure, to honor the fact that the data is your own. Obviously, there are advertising business based models. And, you know, in that case, you don’t pay the company with your money. You do still pay the company, I believe, because you pay by providing the company with access to your data and the company gets paid but the company gets paid by advertisers. And so there is this interesting economic tension, if you will, between honoring the needs of the people who use your service and working with the advertisers who pay you for the data that you were getting.

SREENIVASAN: I feel like right now where information is headed that there could be a future where privacy is the ultimate luxury. That the more powerful you are, the more you’re going to be able to employ resources, to pick up your digital crumbs whether it’s in the cloud or other places. Because there’s so many pieces of my information that are being transacted today that I don’t have any control over, that I’m certainly not being paid for.

SMITH: One of the things that I think is so interesting is the United States has been slow to adopt privacy laws. Europe has really been the birthplace of modern privacy protection, especially since the 1990s. But there’s a really important lesson from the last year. California adopted a sweeping privacy law. You might ask but why California? The answer is very clear. It’s because they have a ballot opportunity. You can put an initiative on the ballot and once people look at the polling, they saw that more than 80 percent of the California voters were likely to support this. That shows you where the public voice and interest is. And I think that is a voice that we need to listen to regardless whether we create technology or we’re just like, all of us, we use it. We rely on it every day. I think ultimately we need a national privacy law. I gave a speech in 2005 saying this and most people in the tech sector just yawned. But I think now people are awake and ultimately national law would serve us best. It there’s not a national law, the California law will be the de facto national law of the United States.

SREENIVASAN: In the book, you write about a few moments in the past few years that increased our awareness of data. 2013, Edward Snowden’s revolutions, also, another big moment. 2018, Cambridge Analytica. So what does Microsoft do to, I guess, maybe police either your clients or access to any of our information?

SMITH: Well, the first thing I would say is this decade has had these two critical inflection points. 2013 with the Snowden disclosures was the awakening of where data was being used in the U.S. government. 2018 with Cambridge Analytica was a political awakening, especially, with concerns about what companies were doing. And so to really answer your question, I think it starts with exercising more self-restraint, having clear principles on how we think about data, how we use data. But it actually, also, really requires creating the technology tools so that every business, every government, every nonprofit can manage its data in a way that protects privacy, both privacy as required by laws that are changing, privacy with changing expectations among people.

SREENIVASAN: One of the big revelations also in 2018, or 2016 I should say, was the integrity of our elections. I mean the U.S. Intelligence agencies said there’s been multiple incursions by other state actors, Russia and others. Also, around the election, there was this reckoning that technology companies certainly were ones that owned the platforms are enabling the spread of misinformation and disinformation in an unparalleled way. I mean to what extent are platforms or should platforms be responsible for the information that is trafficked across them? I mean, the United States has a rule basically that indemnifies the tech companies but other countries don’t.

SMITH: When we see these kinds of threats to our democracy, we all have a responsibility to take action. That means if you’re a tech company, first thing I would say is, regardless whether you have a legal duty, I think we have a civic responsibility to step up. And I would be the first to say companies are. We have more to do and we always will, I think. But then the second thing is governments need to do more, as well. It’s good for governments to put more pressure on companies to do more. But there’s no other area where you would say, oh, we’re going to defend the country from foreign threats by just asking a bunch of businesses to do more. That is almost a quintessential responsibility of the government. And it needs a collaboration, new forms of collaboration, if you will.

SREENIVASAN: You’ve been responsible for leading the Paris call for trust and security in cyberspace. The U.S. is not a party. Neither are Russia, Iran, China, Israel. These are major actors. So even if you have a coalition of the willing, when you don’t have these major actors in the game agreeing to the set of rules —

SMITH: Well, with the Paris call on cybersecurity, we have a clear goal. It’s to bring together the democracies of the world with nonprofit groups and businesses of the democratic nations to protect the internet, our fundamental infrastructure from attacks. Attacks, that in some cases, are obviously coming from nondemocratic nations. You know, in the world today, there are roughly 75 democratic countries and they have roughly half the world’s population. We are disappointed that the United States hasn’t signed the Paris call, but 67 nations have. Most of the democratic societies of the world are working together. All 28 members of the European Union, 25 of the 27 members of NATO. To me, it’s a great example of a coalition of the willing. Keep working, keep building, the day will come when the U.S. thinks.

SREENIVASAN: You’re an optimist?

SMITH: Absolutely.

SREENIVASAN: Right now, at least on the political campaign trail, on the Democrat side, there’s definitely a push to break up tech companies that — and the platforms and essentially these near monopolies are stifling competition. You’ve heard all these arguments before. You’ve lived through them. What is the piece of advice that you’d give to the companies that are now under the, you know, watchful gaze of the attorney generals around the United States?

SMITH: I think the most important thing that we learn when we had our years on the hot seat was that you have to look at yourself, you have to see what other people see in you. And unfortunately, that’s never as positive as what you think you see when you look in the mirror. Understand their concerns and start to address them. Be prepared to comprise. Our fundamental message is, if you create the technology that changes the world, you have a responsibility to help address the world that you have changed.

SREENIVASAN: Recently, some of your employees protested your decision to go forward with the $10 billion contract at the Pentagon. You wrote on Microsoft Blog that, listen, you’ve been working with the Department of Defense for 40 years. You’re going to stay engaged. You’re going to be proactive. This is a way that you can influence the policy from the inside. But can you give me an example of how you have used your position inside different government agencies to advocate for something that perhaps they didn’t think of in a way that is respectful of privacy?

SMITH: Sure. Well, one of them is what is what’s happening with facial recognition. Because facial recognition is important for privacy, it’s important for people’s broader rights. You know, and we’ve turned down deals in nondemocratic countries where we would see human rights put at risk through broad based facial recognition, but even in the United States. We’ve shared there was a law enforcement agency in California that came to us, they wanted to put cameras in every police car, use facial recognition to identify whether the people being pulled over for any purpose at all were a match for their data base. We said no. We said, look, this technology is not ready or suitable for that purpose. It is likely to be biased and lead to falsely identifying people, especially people of color and women for whom the data sets are just not as strong. And we then work with that law enforcement agency. We’re advocating for legislation across the country to, among other things, address that risk of discrimination.

SREENIVASAN: How concerned should people be about facial recognition and the data that’s being gathered by companies and countries as I walk through the streets in my life right now?

SMITH: One of the reasons we devoted a chapter in our book to facial recognition is because, perhaps, it’s becoming almost a quintessential tool and potential weapon. It’s one reason we advocate strongly both for governments moving faster, if there is any single area where I just feel we need urgent action by governments, it’s to start adopting laws in the field of facial recognition. But at the same time, we shouldn’t just give companies a pass. You know, that’s why we have said we’re taking the principles that we are encouraging governments to adopt the law and we’re applying them to ourselves immediately. I think people should be asking everybody in the tech sector to do more of that.

SREENIVASAN: You know it seems that China right now is going to use facial recognition and artificial intelligence in a totally different way. They want an ordered world and they want this technology to help them control dissident, et cetera. Russia, on the other hand, might be using it to start a different cold war and use all these technologies to spy on and maybe even disrupt elections and so forth. The United States doesn’t seem to have some sort of coherent strategy on how we want to harness the power that is inside A.I.

SMITH: You raise, I think, a fundamentally important point. In our book, it’s, in part, a call to action. In the United States, in the democratic societies of the world, if we want to protect values that we think are timeless, like democratic freedoms, human rights, we do need a more coherent approach in the United States across the democracies of the world. And, you know, we need to get after it. We can’t just study this and debate this and watch gridlock continue to unfold in Washington, D.C., or elsewhere. That’s why we, frankly, are appealing to everybody trying to make these issues more assessable to all of us who are affected by them so the public voice can be heard.

SREENIVASAN: Look, I totally hear what you’re saying about democratic values and human rights. And somebody is going to watch this interview and say but what about all the data centers they have in China right now? And at the same time, you’ve got possibly a million, million and a half Uighurs in the western part of the country that are in reeducation camps in 2019.

SMITH: Well, actually, you know, one reason we devote — it was the hardest chapter in the book to write about, China, is because the complexity of these issues. There are certain services that we’re comfortable putting there. You know, services for businesses and the like. But, you know, consumer data, consumer e-mail service, we don’t have that in China. We don’t have that in certain other countries. We don’t put that kind of data in certain countries because whenever you put data about somebody in a country, you put that person’s most precious information potentially at risk. You have to think long and hard. We need people to be thoughtful before we just build these data centers everywhere and put all the data in the world in them.

SREENIVASAN: You know you are the longest serving executive now at Microsoft in 26 years. What is the biggest argument that you lost where you wish you could say to everyone see, I told you so, we should have done this?

SMITH: Well, you don’t become the longest serving anything by being the one who walks around saying I told you so. That’s usually not a recipe for success. We have learned so much over the year. And, you know, not surprisingly, you know, as somebody who was in the middle of the anti-trust issues, at least to some degree in the ’90s, you know, I was very happy when we all had the opportunity to learn some lessons that were so important about what it takes to, you know, just sort of step up and connect with people, companies, competitors, governments, the public. And, to me, a lot of life is about variations on that theme. Think about the long-term. Listen to what other people have to say. Be curious about their point of view. But perhaps most importantly, think about the public interest. You know, there was the old story of, you know, the CEO of General Motors who long ago said that what was good for General Motors was good for America. I have the opposite view. I believe that what is good for America will be good for Microsoft. We are the product of the values of this kind of democracy. And if we need to adapt to serve democracy, we should. And when we do, we’ll do well.

SREENIVASAN: All right. The book is called “Tools and Weapons.” Brad Smith of Microsoft along with Carol-Ann Brown, the coauthor, thank you so much for joining us.

SMITH: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

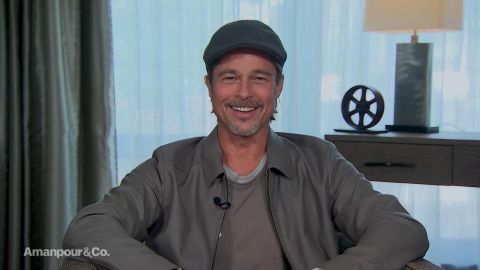

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet discusses the climate crisis and the upcoming UN General Assembly with Christiane Amanpour. Brad Pitt joins the program to explain the roles that masculinity and vulnerability play in new space epic “Ad Astra.” Microsoft President Brad Smith sits down with Hari Sreenivasan to grapple with the ethical questions that come with new tech.

LEARN MORE