Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

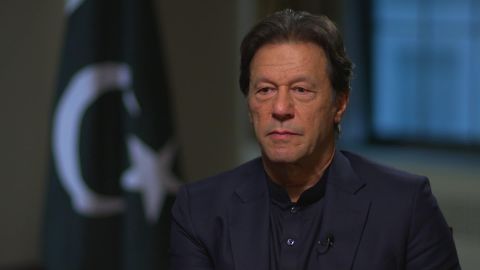

IMRAN KHAN, PAKISTAN PRIME MINISTER: I fear there’s going to be a massacre.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Pakistan prime minister, Imran Khan, warns of a bloodshed in Kashmir. A candid interview after tensions rise with India’s crack down.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

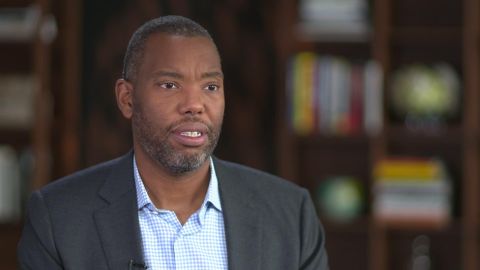

TA-NEHISI COATES, AUTHOR, “THE WATER DANCER”: And so, “The Water Dancer” is a book about freedom. It’s about a young man who is seeking freedom but

does not quite understand how complex that request actually is.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Acclaimed author, Ta-Nehisi Coates, takes us inside the magical and devastating world of his first novel “The Water Dancer.”

Plus, the mayor of San Francisco, London Breed, tells her incredible story, how she rose from poverty to City Hall.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in New York, where all week world leaders have been descending on the United Nations to

debate big topics like climate change and tensions with Iran.

Today, the Pakistani prime minister, Imran Khan is desperately trying to elicit the world’s support for his country and move another topic to the

top of the agenda, and that’s Kashmir. It’s a disputed territory between India and Pakistan. And once again, it’s a flash point between those two

nuclear neighbors, after the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, stripped the territory of its antonymous status back at the beginning of August,

imposing a draconian curfew and cutting off millions of Kashmiris.

India says it’s trying to achieve lasting peace. And Modi is popular with President Trump who gave him a rock star welcome to the United States last

week at a 15,000 strong Indian-American rally. But Trump has also met with Imran Khan and offered again to mediate.

And I sat down with the Pakistani leader as both took their case to the world at the U.N. General Assembly.

Prime Minister Imran Khan, welcome to the program.

KHAN: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So, tell me, first and foremost, what message do you want to send from here? What do you hope your visit will have accomplished?

KHAN: Look, Christiane, I wouldn’t have come to the U.N. G.A. because, you know, we have just emerging coming out of a very difficult economic

situation. And so, my presence is required in Pakistan.

What has happened in Kashmir is so alarming and I realize that the world doesn’t fully understand what is happening there. And what is happening

can only get worse, 8 million people have been locked inside now for 50 odd days. And the world doesn’t seem to understand the gravity of the

situation. Because the moment the curfew is lifted, there are 900,000 troops there. And I fear a massacre.

AMANPOUR: Indian troops?

KHAN: Indian troops. And I fear there’s going to be a massacre. Because people in Kashmir for the last 30 years have been demanding the right of

self-determination, there have been demonstrations. Last five years, ever since Narendra Modi’s government came, the level of oppression has

increased. There have been United Nations reports on the human right abusers.

AMANPOUR: You’re here at the United Nations, both you and Prime Minister Modi are addressing the world. There is a U.N. resolution that governs the

fate of Kashmir. Do you have any hope that might you meet with the prime minister of India bilaterally or a pull aside or whatever you do even if

it’s not a 1,000 percent formal?

KHAN: There’s no question of me meeting Prime Minister Modi of what he’s done in Kashmir. This is only a mindset which believe in a Hindu

superiority which does not believe that other human beings are the minorities, other religions are equal citizens. Only that mindset could

have done this.

I mean, how could anyone do this to other human beings? Shut them up for over 50 days. What does he expect? Even animals if they’re shut inside

for 50 days, no hospitals, no schools for them, even then the world would have reacted.

AMANPOUR: Why do you think the world is not reacting? Remember when Putin went into Crimea and annexed Crimea, there was sanctions, there was an

international uproar that, frankly, continues to this day. Why do you think the same has not happened when Modi has essentially — potentially

annexed Kashmir?

KHAN: Well, I have apprised almost all the top war leaders. I’ve explained to them the situation. There are 11 United Nations Security

Council resolutions which give the Kashmiris the right of self- determination and that is a disputed territory. It’s not an Indian territory.

First of all, a lot of leaders didn’t realize this. But I think even the ones who realize look upon India as a market for 1.2 billion

people and trade and so on. And this is the sad thing, material over the human.

AMANPOUR: And you’ve said that the world appears to be appeasing India.

KHAN: Let’s get one thing right. Narendra Modi represents RSS. He’s a life member. RSS was this ideology which came about in 1925 inspired by

Adolf Hitler and Nazism. They believed in the ethnic cleansing almost (INAUDIBLE) from India. This ideology had A, the idea of Hindu supremacy.

And B, hatred against the Muslims.

They consider themselves higher race. So, this racial superiority, ideology, it was responsible for the assassination of Mohad Mogandi who

they believe was soft on Muslims. It was banned three times in India as a terrorist organization. These extremists have taken over India.

AMANPOUR: Now, he is a very good friend and ally of President Trump. And President Trump, in fact, speaks warmly of both of you and he says that

he’s had great meetings with you and great meetings with Narendra Modi and he is willing and able to help and intervene, if you should want.

KHAN: President Trump, head of the most powerful country in the world, his best place to do something about this. At the moment, he’s saying to

Narendra Modi, I want to help but Modi wasn’t want to. Why doesn’t Modi want it? Because the moment this becomes internationalized, other

countries come in and mediate, they will realize that the poor Kashmiris were denied their right for self-determination and they will know what the

human right abusers are — which are going on in Kashmir.

It’s massive. Security forces which have locked in these people. So, Narendra Modi does not want any outside people to mediate. He keeps saying

it’s a bilateral relation. When we try to talk to him, he says, it’s a unilateral issue. So, we go around in circles.

But eventually, and this is my belief, this is what I think I’ve achieved from my trip here, I believe that the international community will move in.

They will have to because this is going to become a flash point.

AMANPOUR: And, of course, for people outside and maybe even few inside, everybody is very aware that you’re both nuclear powers, that there have

been wars fought between you over this very issue in the past. And they’re concerned this might, as you say, it become a flash point but a terrible

flash point. What can you say about — what would your reaction be? How far are you prepared to go?

KHAN: Christiane, that’s why I’m here. If it was just something which would have remained localized between India and Pakistan, even if a

conventional war, the world is not really pushed about it, but this can go out of control. And I’ll tell you how. What are the narrative of Narendra

Modi’s government is that the Kashmiris want this, this whole thing has been done to make Kashmir prosperous and developed, and Pakistan is the

spinner (ph) in the works by sending in terrorists. They’re already accusing us that the — I think the —

AMANPOUR: They are saying it again, the military chiefs that 500 camps are being used and Pakistan is mobilizing militants in Kashmir, terrorism.

KHAN: This was predictable. Why are they saying it? Because they want to divert the world’s attention from what is going to be a massacre. So, to

divert the attention, this is the mantra that the Islamic terrorism. And Islamic terrorism since 9/11 has meant that the world just looks the other

way. You can violate all the human rights. You can do anything of those people by calling them Islamic terrorists. That’s what India has done,

Narendra modi.

My point is, what is Pakistan going to get out of this by sending in 500 terrorists? There are 900 — almost a million troops there. What are they

going to do there? The only thing they will do is that the — on the pretext of going after terrorists, they would be more oppression off the

people of Kashmir. And secondly, they will divert the world’s attention towards Pakistan.

And so, I have specifically told Pakistan, people of Pakistan, anyone going into Kashmir will be an enemy of Pakistan and an enemy of Kashmiris for the

reasons that I’ve just told you. It’s the first time two nuclear armed countries are face to face. If this goes like it happened in February, I

mean, we immediately return the pilot when we shot down the plane because we didn’t want any escalation.

AMANPOUR: And actually, the world thought that you had behaved very responsibly in pulling back from that.

KHAN: And I told the Indian public, also, I said, look, if this goes further, it will soon spiral out of control beyond my hands and your prime

minister’s. And guess what, you know, Narendra Modi, once we returned the pilot, his entire election campaign was that Pakistan is so scared of me

that they immediately returned the pilot and I’m going teach Pakistan a lesson.

And this was a trailer, the film is about to start. The whole election campaign was this jingoism, this whipping up hysteria, war hysteria against

Pakistan, and he swept the elections. In six years, India has changed. And I fear it is just going to change even more rapidly. That’s why I call

it appeasement because the world should take a stand. You do not, in this day and age, put 8 million people in an open jail, surround them by 900,000

troops.

AMANPOUR: There are also other huge other flash points going on even around your neighborhood and that is the tension between Iran, the United

States, Saudi Arabia and the countries over there. You met President Trump. I think he asked you to do what you could in mediating maybe with

Iran. I don’t know. And you met the president of Iran as well.

What can you tell us about any behind the door’s diplomacy, behind the scenes movement in that regard?

KHAN: Well, firstly, Christiane, it’s so important that this conflict does not take place because apart from anything else, I mean, we already have

Afghanistan on one side, this Indian problem on the other side. The last thing we want is a conflict on the other border in Iran and U.S. and

possibly Saudi Arabia, UAE. It will be a nightmare for us.

We are coming out of this very difficult situation where we had a massive current account deficit and we’re just getting ourselves right. If the oil

prices again shoot up, I mean, not only us, it’s going to affect so many countries in the world, probably cause more poverty and God knows how long

it will go. Because, you know, so dangerous when people say that, you know, it will only be a short war. To be fair to President Trump, all his

instinct is against the war.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

KHAN: I know there are people pushing it. I feel this will be awful once it starts. So, we should do everything to stop it. And I’m trying my

best. I spoke to President Rouhani. And, you know, let’s see how it develops.

AMANPOUR: At the beginning, you were talking about the dire financial straits that Pakistan has been in. That you should be there because you’ve

got a major economic crisis, which you’re trying to fix. You were against an IMF intervention or IMF assistance and then you accepted it. Why have

you decided that going forward the IMF is a better course of action?

KHAN: Christiane, we inherited the biggest current account deficit in our history. It was such a huge gap that until we fixed our — increased our

exports, (INAUDIBLE), there was a time lag. In that time lag, we had to service our debts. We had to service $10 billion worth of debts which have

been accumulated by the previous government.

How we’re going to do it, unless we didn’t go to the IMF. We could have defaulted. They could have been run on the rupee, you know, and the

economy could have tanked completely. So, we have gone through a difficult period. And mercifully, thank God our exchange rate has stabilized. We

lost 35 percent of value on our currency, which, of course, caused inflation which has hurt our people.

But at least now we are stable and the signs are — export sign increasing now. The economies on the main country has stabilized. So, it’s a great

opportunity now to build on this.

Now, we have campaigned for anti-corruption. We come into power. So, when some — the problem — this is where the problem starts. Now, we are

trying to collect taxes because we have to collect taxes, you know, to service our debts.

AMANPOUR: Bisan (ph) was famously unable to collect taxes.

KHAN: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean, for years people weren’t paying taxes.

KHAN: So, the last two months, we have been — via the reforms we did, we have collected record taxes the last two months. Now, the problem is, the

reason why people are paying taxes and we feel people will pay more and more taxes because they trust the government. It’s a credible government.

AMANPOUR: I think successive Americans president and successive partners who wished that Pakistan would, you know, realize that its biggest threat

was from Afghanistan and then unstable border with Afghanistan. Can you say that Pakistan is no longer in the throes of that kind of militantism

that has turned off your international partners for so many years?

KHAN: Well, first of all, Pakistan was not responsible for the U.S. not succeeding in Afghanistan because there were 150,000 NATO troops. The

biggest military machine ever. And we are being blamed for them not winning in Afghanistan. And we were almost told that the problem is not

with Afghanistan (ph). That’s the haven for all the terrorists and so on.

If the problem was not with Afghanistan (ph), the U.S. should have exceeded in Afghanistan. In fact, the things are even worse now than before. So,

clearly, the problem lay with a history of Afghanistan. They have always stood up against anyone invading their country. I mean, there

was history with Soviets, then with British before that.

The — I just felt that the U.S. trying to find a military solution in Afghanistan when there was never one. And finally, sense has prevailed

that now there’s direct dialogue had started and supported by Pakistan and I feel really sad that in the middle it was scuttled. But I do feel and

we’re trying and when I spoke to President Trump, we are trying to, again, get the talks back on. Because, as I repeat, I repeat there is no military

solution.

AMANPOUR: Imran Khan, thank you very much indeed for joining me.

KHAN: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: And we continue to request an interview with the Indian prime minister, Mr. Modi.

Now, we leave that real world temporarily for the magical with our next guest, the acclaimed African-American author, Ta-Nehisi Coates. His award-

winning work has put him in at the very heart of the public square these days with nonfiction like “Between the World and Me” that dissect being

black in America. To comic books like “Black Panther.”

Coates is now venturing into fiction with his first novel called “The Water Dancer.” Using the vehicle of magical realism to tell the deep and

disturbing story of slavery and the trade in human beings and the underground railroad which shuttled them to freedom. Coates join me as his

novel, one of the most anticipated of the year, hit the bookstores.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, welcome to the program.

COATES: Thank you for having me, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: So, you are very well known for your nonfiction writing. And now, you’ve sort of branched out of your comfort zone with your first piece

of fiction, this novel.

COATES: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: “The Water Dancer.” Why?

COATES: Well, I think the thing folks should understand is the way this happened in terms of timing. In fact, “The Water Dancer” is older than,

you know, some of my other work. For instance, it’s older than (INAUDIBLE), it’s actually older than “Between the World and Me.” I

started “The Water Dancer” in 2009 after my first book. Actually, at the suggestion of my agent and my editor.

And during that period, I was doing a lot of, you know, reading around slavery and the civil war and I found myself wanting to live in this period

for some time. I didn’t anticipate living in it for 10 years. I didn’t anticipate it taking that long but, you know, other things happened.

AMANPOUR: Was it that because other things happened or was it just so difficult to write such a profound story?

COATES: You know what, it was a combination of both. I probably didn’t know — and even as it was happening, didn’t understand the level of

difficulty. I really didn’t understand it until I was done. But it was because of other things but it was good those other things happened because

what it would do is, you know, it would give me a break for a moment from it to think about it, you know, to develop a little bit, come back and look

at the text again and see things that maybe I was missing before.

AMANPOUR: So, given it took so long, 10 years, and actually, the discussion is moving rapidly on racism.

COATES: Yes, it is.

AMANPOUR: On slavery.

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And we’re here in 1619 plus 400.

COATES: That’s right. That’s right.

AMANPOUR: What have you learned over those 10 years? What, in your mind, in your view of that historical past or the present has evolved over those

10 years?

COATES: So, I have to tell you, the conclusions I probably have now, even conclusions I had in 2014 or 2015 when, you know, I published “Between the

World and Me,” I didn’t have them in 2009. I actually did not understand, at that point, the extent to which slavery ran through the spine of this

country. I didn’t understand the foundational aspect of enslavement.

“The Water Dancer” — and I would say, I guess, much of the work I’ve done over the past 10 years, comes out of that. This feels like, you know, the

capstone on a long project that began back then, you know.

AMANPOUR: So, we’ll get to the big picture in a moment but let’s talk about the small picture.

COATES: Sure.

AMANPOUR: The narrative in your book. Hiram Walker —

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — is the narrator or the main character, anyway. And you’ve endowed with all sorts of mystical and magical properties. He’s the memory

thing. I think you call it conduction.

COATES: Conduction, yes.

AMANPOUR: Is his particular gift.

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: He also, I guess, like many little boys and girls, saw his mother sold off into slavery.

COATES: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: And, and I didn’t quite get this until the second chapter, he’s also the son of the white master.

COATES: He is, yes.

AMANPOUR: Who is now tasking him with looking after his white brother.

COATES: His white brother.

AMANPOUR: It’s so complex.

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Tell us about Hiram Walker. What were you trying to tell the world through this boy?

COATES: There is a central trope running through “The Water Dancer.” At its core, it’s a book about memory. And how I — and I knew — I was

pretty sure I wanted to write something about that, that I had. I moved to it being more of a supernatural, you know, aspect, in those mystical

properties that you talked about because through much of the research I did, I actually had to read quite a bit of the literature of the

first person accounts of enslaved black people of that period.

And the way they talked about their experience was mystical. Oftentimes, they would talk about escapes. They would use, you know, sort of mystical

language. Frederick Douglass would talk about another enslaved person who gave him a special group that would help him escape. There were, you know,

methods that, you know, they believed in to help, you know, for instance throw off the dogs that were on their trail. So, it’s a mystical world

that they lived in.

Hey, I’m always attracted to that. I grew up on comic books. So, I had a natural attraction to that. And so, I just sort of I dug right into it.

Harim is a young man who has a pretty natural sense of memory except when it comes to the things most intimate and arguably most important about

himself.

And so, “The Water Dancer” is a book about freedom. It’s about a young man who is seeking freedom but does not quite understand how complex that

request actually is.

AMANPOUR: Fill in what you were just saying, except when it comes to the most important things about himself.

COATES: So, in this case, he has — he understands as a fact that his mother was sold off but he doesn’t remember his mother. He can’t, you

know, remember her face. He can’t remember her doing things for them. He only knows what other people have told him. And I think what becomes

pretty clear is that his act of forgetting is to, some extent, intentional. He has a mental block of. He can’t face what it means that his mother has

been sold off because then he would have to draw certain conclusions about his father and indeed, the very world that he lives in.

AMANPOUR: Well, we’re going to talk about that. He does, actually, magic up his mother.

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: He has this incident where by — and it’s very associated with the water. I don’t want to be a spoiler alert.

COATES: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: But he’s hovering between life and death and he sees his mother.

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Rose.

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And then, the story gets into how his father, this white master, sort of decides that he likes him, that he’s clever, that he wants to

educate him.

COATES: Right.

AMANPOUR: Not many black slave boys are educated.

COATES: Right.

AMANPOUR: Describe the farmer who he does know.

COATES: So, I think what happens is the father — Harim’s father, Howell Walker, loves his son about as much as any white man in that system and in

his position could love his black son. And what that results in is some degree of privileges that are afforded to Hiram. But nevertheless, he is

still enslaved and he feels it. He feels it.

The father — and this is, I guess, one of the more interesting perspectives for me being a writer, even characters who, if I describe them

to you, or somebody described them to me, I may not sympathize with. As the writer, you have to find your way into those characters anywhere. So,

I had to find my way into the father, Howell Walker. He’s a man who is born into a system, a system of enslavement that is responsible for

everything that’s around him. It’s responsible for the food he eats. It’s responsible for the clothes that are on his back.

Slaves do all the work. Slaves built the house. Everything around him. The world and everyone he knows, everyone in his class, in his society,

lives off the product of the enslaved. And so, that imposes certain things on his mindset and his ability, specifically on his ability to, you know,

love his black son.

AMANPOUR: You use words like the tasked for the slaves, the quality for the owners, (INAUDIBLE) way to sort of symbolize selling off into slavery

into the south. And we’ve said Hiram’s father is the plantation owner. At one point he says in the book, it’s not fair, I know. None of it is fair

but I’ve been damned to live in this time when I must watch my people carried off across the bridge and into God knows where. He’s kind of

pitying himself.

COATES: Yes. He’s the one sending them off. He is the one doing the sending. You know what I mean? But I don’t think that is so different

from how people who harm other people often try to justify it. Look what you made me do. And so, yes, that’s a relatively tough moment, you know.

But one of the interesting thing is, again, I keep going back to this, but if you read the literature of those who were doing the enslaving of the

planner (ph) class, they were wonderful at justifying, you know, the selling, you know, of other people. Thomas Jefferson, you know, famously

says, you know, living off — living in — you know, the system of slavery is like holding the wolf by the ears, you know, you dare not let him go.

Well, yes. But the wolf is actually a person. You know what I mean? You made a decision to grab the wolf by the ears. That wasn’t, you know, a

thing that was done to you. So, I think people are very good at finding ways to justify, you know —

AMANPOUR: Look, you’re a young man and you are exploring this very heavy history, America’s original sin. Right at the time when we’re confronted

daily with all aspects of this racism. And particularly, in very, very interesting investigation in the “New York Times” with the 1619 Project.

And she lays out, Nikole, in absolute forensic detail how American music is all black music, how America’s economy was the commodity of people, slaves,

how the health care was completely and utterly stacked against black people, how everything was so unjust.

And I just wonder, with all your reading because you did a huge amount of the original research, are you angry? How angry does it make you feel?

COATES: Anger, not too much. I mean, when you’re in the moment, there are moments. OK. I, for instance, I did a lot of research down at Monticello.

I was angry when I was at Monticello. And I was angry because Thomas Jefferson is brilliant. If you want to read a contemporaneous account by

someone from the planner class to describe the evils of slavery, you don’t get much about it in Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia.

It’s brilliant, brilliant (INAUDIBLE) of how corrupted slavery is. And yet, here you are on the property of someone who lived off of the backs of

hundreds of people. And not only lived off of their backs, went into debt buying, you know, expensive finery, champagne, you know, living the life of

a king so than when he died, those people who he was, you know, allegedly responsible for were, in fact, sold off and those families were broken up.

And they all suffered for a man who knew that what he was doing at every hour was evil and was wrong.

AMANPOUR: And who is lionized throughout history.

COATES: And is lionized throughout history. And I understand why. You know, here’s the change (ph). I make no, you know, mistake — make no

mistake about that, but that’s hard to take. It’s hard to take when people know and you can tell they know and yet, you know, nonetheless, you know

what I mean, they fail to act.

But if you’re continuously angry all throughout, you can’t write. You can’t write. It would destroy you. You know what I mean? You would lose

the ability to try to represent, you know, everyone with some degree of sympathy.

AMANPOUR: And yet, I mean, a lot of the aspects that come through in this book exist today. I mean, first and foremost, child separation from their

parents.

COATES: Yes, it does.

AMANPOUR: It’s happening right now.

COATES: Yes, it is. And I was not unaware of that. You know, as we got toward the end, you know, of our publication cycle. What I think is when

you have a country that in its, you know, nascent colonial roots, in its early history, practiced a policy of family separation for profit, when at

the end of, you know, the civil rights movement, I would argue practiced more family separation through the expansion of the cultural state of this

country, when, you know, post — after the civil war, practiced a policy of a family separation through our convict leasing wherein, you know, people

had committed petty crimes were sent off to jail, fathers, very often, if that becomes part of your history, if it’s something that society

practices, it becomes easy to then, therefore, practice it at the border.

And so, I think those of us who are somewhat familiar with that history are not surprised to see kids in cages. It’s not the first time we’ve done

this.

AMANPOUR: It’s actually hard even to hear you say that, kids in cages. Can I ask you about the secret world of slaves, which, obviously, you

explore —

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — so incredibly. I want you to read a passage from the book. It’s where Hiram, the main character, observes a group of enslaved men and

they gather together at a local horse race.

COATES: “I looked over and watched as the other colored men along the fence shouted and laughed with still others working the stables. I’m

watching this silently as was my way, I marveled at the bonds between us. The way we shortened our words or spoke sometimes with no words at all.

The shared memories of corn shuckings, of hurricanes, of heroes who did not live in books but in our talk, an entire world of our own hidden away from

them. And to be part of their world, I felt, even then, was to be in on a secret, a secret that wasn’t you.”

AMANPOUR: Tell me a bit more about that hidden world that they shared.

COATES: I often say that, you know, there are two aspects to being black in this country. There is the racial aspect. The idea of being raced,

literally being inserted into a member of a black race because you have African ancestry. None of us enjoy that. We would like that to go away.

All of the racism that happens to us proceeds from the justification that we are part of a race.

But one thing that’s happened out that have process, and I don’t think black people are original in this, is out of that process of being raced

and oppression, a culture has come about, an ethnicity that is totally different. The music you listen to, the food you eat, the way you talk,

the easy intersection between other people who are of that ethnicity and culture, and we love that.

I attended Howard University and loved my time and enjoyed my time there. One of the things I loved most was the cultural aspect of that.

And so while all of us would get rid of the racial aspect about identity, in a day, in a minute, the cultural aspect is very very important to us.

And so I always try to make sure I’m writing about that. You know, when I’m talking about, you know, African-American because I think that part

shouldn’t get missed.

AMANPOUR: Can I just — I mean it’s a little bit of a hard turn here, but you talked about the cultural aspect and the celebration of that. You

talked about kind of being raised on magical, mystical because of comics and all the rest of it.

Well, I mean you are the sort of author of one of the most incredible comics. You did “Black Panther.”

COATES: Still do.

AMANPOUR: And, of course, the film was just such a roaring success.

COATES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean how do you digest this movement that you created?

COATES: Well, I think storytellers have a specific advantage. African- American storytellers have a specific advantage and that is because, for so long, much of society wasn’t really interested in their stories. That

means there’s a whole mind there to be explored.

The flip side of Tarzan and the flip side of some of the more unfortunate stereotype portraits of Africa is that they’re so dehumanizing and so far

removed that it means that most people were raised on those images. People who created those images, also, had no real interest.

And so what that means when you come in, you know, as a storyteller, you have a wide open field that hasn’t really been explored in the way that you

want. You don’t have to go compete with Clint Eastwood, you know what I mean, to do like a western or something like that.

And so I think that’s what you’re seeing. I think you’re seeing storytellers having their moment both because if so much unexplored terrain

but also, you know, for the first time in history, there are enough Americans who are comfortable with those stories that you’re seeing big

media entities get behind them also.

AMANPOUR: Do you think this spike of white nationalism that we’re seeing, white supremacy that we’re seeing in this country as well as other

democratic nations, is transitory, is here to stay? Do you think there’s enough of a backlash now two years in against it? Where do you see it it

landing?

COATES: I don’t know. I don’t know. I think the inspiration for the Trumpism is here to stay.

I don’t know if Trump is here to stay but I think the inspiration is here to stay. I think the dangerous thing about 2016 is it became clear that

this was a path that there were enough, you know, Americans. Not a majority but a significant minority of Americans and that you could, you

know, our political system was set up in such a way that if you can mobilize that group, you know, there are desire for cruelty, to see other

people hurt with such that it could carry you all to the White House.

And so it would not surprise me if another politician observing that who perhaps is more intelligent than Trump sees that and uses that same path.

And it is deeply sad to see that be unveiled in that way.

AMANPOUR: You mentioned at the beginning, the idea of reparations and you spoke just recently, this summer in June before Congress, the case for

reparations. You know, you’ve helped rekindle this whole debate and I spoke to Brian Stevenson, the great justice lawyer, and I asked him about

that and this is what he said.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BRIAN STEVENSON, FOUNDER, EQUAL JUSTICE INITIATIVE: We should all want to repair that damage to recover from that history and to create something

better. If we don’t want that, we don’t want a better future. We don’t want a nation that can truly be the home of the brave and the land of the

free.

I don’t think these things should be debatable. The question is how we do it but we can’t even get to how if we’re not prepared to acknowledge that

we must do it.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Where do you see this reparations conversation going?

STEVENSON: I learned a long time ago to get out of the prognostication game. Because I have to tell you, when I wrote the case for reparations, I

didn’t believe we have congressional hearings. I didn’t see that coming. I didn’t see it, you know, being an issue on the democratic primary. That

was not a thing I was prepared for.

But I think one thing that Brian gets at is before we get to, you know, plans, before we get to how is this done, before we get to XYZ, we have to

have some sort of agreement around the idea of actually studying and figuring out exactly what happened and what the cause, you know, of that

was.

That’s why I testified because I deeply, deeply believe in the important significance of HR40. When I began writing about reparations, and I would

admit even in my eyes before I began writing about it, it was considered a wild-eyed, you know, idea who basically —

AMANPOUR: A radical leftist idea.

COATES: Yes, the radical leftist idea. But sometimes radicals are right. And in this case —

AMANPOUR: There hasn’t even been truth of reconciliation. Other nations have done that.

COATES: There’s not. There’s not.

AMANPOUR: Germany, South Africa, Rwanda.

COATES: Yes. But I think for many people, it presents a deep threat to the American order. Because I actually think more than the money, the

conversation, if you can believe you’re a shining city on a hill, you don’t believe you’re without sin, if you can, you know, believe, you know, that

you really are this special place as opposed to just, you know, a society, a country, generally (inaudible) other countries do, not a particularly

evil place but just a country like other countries, just a state like other state, I think a lot of our policy, particularly even our foreign policy I

would argue, would come into question.

I think we have to be a little bit more humble about how we act in the world. I think we have to be a little more humble about how we act here.

AMANPOUR: I guess finally, I just want to ask you your take on what you’ve been called in public. You’re now called regularly a public intellectual.

Is that a burden? Is that a good thing?

COATES: I don’t enjoy being called that. It’s not how I think about myself but one of the things I’ve learned was that that’s not really up to

me. People are going to say what they are going to say. And if people — I guess there are worse things to be called.

AMANPOUR: There are indeed.

COATES: So if that’s what people say, that’s what people say.

AMANPOUR: Ta-Nehisi Coates, thank you very much.

COATES: Thank you so much, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: “The Water Dancer” is available now.

And we go back to the real world, although you might not believe it, because our final guest this evening has had a life and success worthy of

any fictional novel. The San Francisco Mayor London Breed has overcome poverty and tragedy to build a political career that has gone from strength

to strength. And like many big city mayors, she’s struggling with challenges like rising homelessness and she’s even gone toe to toe with

President Trump over the issue.

She told our Michel Martin all about this latest struggle.

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Madam Mayor, thank you so much for joining us.

MAYOR LONDON BREED, SAN FRANCISCO: Thanks for having me.

MARTIN: How does it feel to be introduced that way?

BREED: Well, it’s amazing because I grew up in San Francisco, born and raised. And just never thought something like this was possible for

someone like me coming from some of the most challenging of circumstances right here in San Francisco. And it really is an incredible honor.

MARTIN: Tell me a bit more about that if you would for people who aren’t familiar with your story. I understand you were raised by your

grandmother.

BREED: Yes. Well, my grandmother, she raised me in public housing. And the public housing of that time, it was really the conditions of the

buildings were just terrible. The mold, the roaches, really the pipes that didn’t work, the challenges of access to water and a number of other

issues, the gun violence, the drug use, the drug selling.

All of the things that you could think of, not only was it in my community, there were a lot of challenges in my family with drug use and drug

distribution. And just watching that and growing up in that environment, it’s easy to think that this is what life is about. And especially because

it existed for so many people that I grew with up.

MARTIN: Well, how did you get the idea that life could be different for you?

BREED: Well, I was lucky to have people throughout my life who invested in me. Even my first job working at this place called the Family School,

which helped women over 18 get their GED.

Showed up the first day, see-through t-shirt, cutoff jeans and didn’t necessarily of course answer the phone appropriately. And the people at

the Family School, they worked with me. They took the time to invest in me and talked about how smart I was and that I could go to college and I got a

lot of potential.

And when the program was over in the summer, they were like we want you to stay. And so I stayed year around. I got paid to do it.

So it kept me out of trouble. I focused on my education and really focused on school and really learned in that environment from people who went to

college, from people who were successful, who were trying to give back and do things in the community.

MARTIN: So how did you get the idea for public service? I mean, a lot of times when people grow up without a lot, the first thought on their minds

is, OK, how can I get more?

BREED: Well, the thing is, I didn’t want to be poor. So the first thought in my mind was how do I do something in life that doesn’t get me arrested,

that doesn’t, you know, put me in a situation where I end up in the streets in some various capacities and, you know, how do I take care of myself?

And that was the first thought. But the other thought was why am I by myself?

Like when I was at U.C. Davis, undergraduate degree, I was lonely because I was going to school with so many incredible people. All of the parents of

the roommates I had, they were all there, day one, moving their kids in.

You know, I just got dropped off by one of my friends who happened to have a car and we piled everything up in the car and I got dropped off and paid

for the gas. Even when I think about, like, the sheets, like, my grandmother — she made sure I took some clean sheets and helped me get

ready but, you know, the dorms they have this extra-long sheet thing and so my sheet fit at the top but didn’t fit at the bottom.

I put my pillow up there. I worked it. I basically adjusted.

And the good news is, that I was in this environment and it really helped me develop but it also made me realize that I was alone, too. And so many

people that I grew up with and people that grew up with maybe similar experiences never make it here.

And that’s really pushed me to want to do something different, to want to go back — to finish, of course, and then to want to go back to the

community and really help change things for the better. Especially because the number of funerals that I was attending, it just got to a point where

people that I loved, you know, it just — I couldn’t even do it anymore.

And it was hurtful. It was painful. And I was like how do I stop this from happening?

MARTIN: When you were first starting to think to yourself, this is a path for me, did you have your sights set on being mayor?

BREED: No. I just — I didn’t think that –before I ran for office, I first ran for the Board of Supervisors to represent my community. But

before I ran for office, I was like my goodness how am I going to raise the money? How am I going to, you know, I don’t have those kinds of resources.

I know people. I’m active in the community. I know what to do to work hard, but how do I make those connections?

And so when I first was running for office, because of a program like emerge, which helps train democratic women to run for office and a couple

of other things that I started looking into, I said, well, maybe I can do this.

But it wasn’t about running for mayor. It was about representing my community and the need to start focusing our attention on the kinds of

policies that are going to actually work because of my experiences with the policies that didn’t work.

MARTIN: But ironically, now that you are mayor, it’s almost as if the problems are outrunning you.

BREED: Yes.

MARTIN: I mean one of the big issues that’s in the public mind now, particularly — I’m sure in San Francisco and elsewhere around the country,

is the homelessness crisis.

BREED: Yes.

MARTIN: How do you understand what is going on here right now with homelessness?

BREED: Yes. I mean it’s so complicated. And it’s not just happening in San Francisco. It’s all over the State of California and it’s a real

crisis.

And it’s a real crisis because there’s a couple of reasons. Number one, so many people that are living on our streets that we’re trying to help are

suffering from substance use disorder, are suffering from mental illness.

And if it were as simple as I have a place for you to live, would you work with me to take on the responsibility of living there and not live on the

streets? I mean, if it were that simple, we would be at a better place than we are now. And it’s been very challenging.

MARTIN: Yes. But haven’t there always been mentally ill people, people with substance problems? The weather here has always been warm. I mean,

it seems like there’s something accelerating here.

BREED: Yes.

MARTIN: I mean according to the San Francisco’s gov.org, homelessness is up 30 percent since 2017. What is happening?

BREED: So I think part of what is happening again are those things and opioids, for example, methamphetamine and those kinds of drugs are just

being used, I believe, a lot more than they have in the past. But also I think that the cost of living and the fact that we haven’t produced enough

housing, housing affordability is at the core of what I know is a challenge for even middle income families struggling to live in San Francisco.

Between 2010 and 2015, the city, we concentrated on jobs, jobs, jobs. We have a 2.6 percent unemployment rate. But during that same time for every

eight jobs we created, we created one unit of housing.

And then it was like a battle between people who are moving here, people lived here, folks who were being pushed out of communities that they were

born and raised in, like my friends and family, and including the public housing that I grew up in.

It was 300 units. It was torn down and only 200 units were built. So there were a lot of mistakes that were made around housing and housing

production and around affordable housing, in particular. Because if we don’t have the places for people to live, that that they can afford to live

in, that’s a big part of why we see even more people living in their vehicles.

MARTIN: So according to PolitiFact, when you factor the cost of living, California is the poorest state in the country. What do you think is the

primary driver? I mean is it the fact that because the economy is so robust here, in part, that the cost of housing is being beat up beyond the

ability for people to pay? What is it?

BREED: I think a couple of things. As I said, we focused in this city on jobs. We didn’t focus on housing.

And then now, even now, trying to get housing built in San Francisco is not just about the money. It’s about the process.

There was one 86-unit building that basically affordable housing that was just opened last year. It took 10 years from the time of identifying the

property to getting it done to opening, you know, up this particular space for 86 families.

MARTIN: So, you know, President Trump was in San Francisco recently. Actually, for the first time since he took office. He told reporters that

San Francisco was “in total violation of environmental rules” because of used needles that he said were ending up in the ocean.

And he said his administration was going to issue a notice of environmental violation because of what he described was its homelessness problem. And

he said the EPA might have to issue a citation. What do you say to that?

BREED: Well, that’s absolutely false. Just to be clear, the president didn’t even step foot in San Francisco. But the fact is, we have a waste

water, sewer water treatment system in San Francisco that has received awards from the EPA because many cities, they don’t necessarily allow for

their waste water to be treated the way our system is set up like in San Francisco.

MARTIN: But what is he talking about? Do you know?

BREED: No. I don’t know what he’s talking about. But I do know that here in San Francisco, that doesn’t occur because of the way our system is set

up.

And in fact, I don’t understand how the EPA would give us an award for having such an incredible system, which is a model for other cities to

follow and take it away. Who knows?

MARTIN: He also — well, his HUD secretary, Dr. Ben Carson, he also recently visited San Francisco. He did drop by a housing development and

he said that the places that have the most regulation also have the highest prices and the most homelessness. He says therefore it would seem logical

to attack those things that seem to be driving the crisis. I mean does he have a point?

BREED: I think that it’s — where is his data? I mean, he’s a doctor. Where is his data to substantiate his claim?

Just to basically draw conclusion without having evidence is, I don’t think, very responsible. But the fact is, we know that there are

challenges with affordability in San Francisco and that’s not a new problem. And so the question is what are they going to do about it?

MARTIN: What are they going to do about it though is the federal government in charge of the regulatory framework for San Francisco?

BREED: I think that they — there are some regulations that — I mean, for example, neighborhood preference and this was a way to provide

opportunities for people to have the right of first refusal in their communities.

HUD has the say over whether or not we can use that particular system for affordable housing. They can decide whether or not they’re willing to fund

or continue to fund a Section 8 voucher or other systems in here which sometimes can make it more difficult for us to either move forward with

redeveloping a project or in any capacity.

MARTIN: Well, to that end, though, he also said that the city should be able to sit down with the state and sit down with the federal government as

opposed to saying this is what we need, this is what we need. If you don’t give it to us, you’re bad people.

BREED: Yes. I don’t believe that we said if they don’t give it to us that they’re bad people. It’s really we can tell you what we need and this is

how we would like to work together and the goal is to try and really make it possible for people to have access to affordable housing in San

Francisco.

So there have been local HUD officials that have worked with us on projects. And I bring up Sunnydale because that was the most recent

example where they worked with us because we couldn’t — we would not be able to rebuild Sunnydale even with private investments, which we need a

significant number of private investments without the approval of HUD. So they still play a role.

MARTIN: Do you feel, though, that in a way that you’re between a rock and hard place here? And here I am going to point out your identity as the

first African-American woman mayor of the city, in a city in which the black population is declining rapidly.

I’m wondering do you feel in a way that you’re kind of caught here as a person who has such important symbolic importance to people because of —

not just because of who you are but because of what you’ve been through.

And yet the solutions have such a long tail that maybe those solutions will take longer than you have time for. Is that possible?

BREED: It’s possible that some of the things I put into play now will take years. And I will say that I’m really proud, of course, to be the first

African-American woman to serve as mayor of San Francisco.

But I’m even more proud that since I’ve been in office, we’ve been able to help over 2,000 people exit homelessness. We’ve been able to get people

housed and build more properties and master lease buildings that we’ve been able to transition people out of shelter beds into permanent supportive

housing.

You know, I’m not going to sit back and think it’s impossible. I think anything is possible. If I can, again, come out of the most challenging of

circumstances and be mayor, then our city, under some of the most challenging conditions we’re dealing with, we can emerge stronger from it.

But it does require good decisions. It does require changes to existing policy. The good investments that will help get us there, it’s going to

take some time.

MARTIN: So what is it like for you as you drive around the places you grew up and you don’t see people who look like you anymore?

BREED: It’s tough because even though we had our challenges with our communities and, sadly, we’ve had really, I mean, the violence and some of

the other issues that have existed but there’s still love. There’s still love for your community.

And when I’m out and about and I see folks, it feels good. It feels good because I do still see people who are still here. There are a lot of folks

who are still here but there’s a lot, lot, lot of folks who aren’t here anymore. And it just definitely feels different.

MARTIN: What is the vision, though, for how this is to be addressed? As you know, there are a lot of, you know, different philosophical opinions

about this. I mean even the term itself gentrification is a political term, in a way.

BREED: I mean a couple of years back when I was on the Board, we passed neighborhood preference legislation. So that when we build affordable

housing in a community, 40 percent of those unit goes to the people who lived there first.

And that had been a challenge because, you know, where I grew up, when something gets built, the people who live there and us kids who were adults

now who wanted to stay in the communities we grew up in didn’t have access to the affordable housing. We would have to compete in a lottery with

thousands of other people and then it completely changed the community.

So that’s part of what I’ve done to try and really, at least — I can’t turn back the clock but what we can do is focus on taking care of the

communities who are here now and making sure that they are not continuing to be neglected in certain areas of our city.

Taking the resources like I was just, you know, in Sunnydale, they’ve been promised and promised and promised. Today, groundbreaking on some of the

new housing development and we’re not going to do what they did when I was removed from public housing. Tear down the units, move everyone to another

city, and then build less units and know they can’t let everyone come back.

It’s like no, you’re staying here. This building is built. You have the option. It’s your priority.

One for one replacement and that’s exactly what I’ve been doing based on my own personal experiences of what I’ve seen that hasn’t worked.

MARTIN: But is it the key to your success here? Do you think it’s your own story that makes people feel that they can have hope again? Or is it

the concrete investments that actually get delivered that make the difference?

BREED: I got to tell you that I’m probably one of the most progressive mayors that the city has ever seen with the number of investments and

policies and things that I’ve put forward in my administration that people didn’t think were possible. Eliminating fines and fees for those who

committed, unfortunately, a crime, did their time, and tried to reenter society so that they don’t have the burden of debt.

MARTIN: And you know this from personal — not to put all your business in the street but you know this from personal experience because you had a

family member who’s incarcerated for some time.

BREED: Yes. Yes. And the fact is, this stuff around criminal justice reform, the stuff around housing, and affordability and really making a

connection between the people who we know need it and access to it, all of those things and how we’ve been able to move things forward has been really

incredible.

And I got to say, I’m proud of my track record. And maybe if it had been somebody else pushing forward some of these ideas, you know, in some

crowds, they may be celebrated more.

But San Francisco is a challenging dynamic. People appreciate it but then they want more. And I understand that because I want more.

I’m a native. I want to change the city and I want people to be a part of the solution of helping to change the city and make it better. And I do

think that part of my story inspires people, you know, to basically know that they can do better in life if they’re in a challenging situation or

others who feel like, you know, maybe this is the right solution if it’s something different than what I’m used to even though I might be

uncomfortable with it.

MARTIN: Alright. Madam Mayor, thank you so much for talking to us.

BREED: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: And that interview rounds out a week of important conversations that explore all the challenges facing our cities, our states, and our

world.

That’s it for tonight. Remember, you can always follow me, Michel, and the show on Twitter.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS, and join us again tomorrow night.

END