Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: President Trump faces the fury of his own party over Syria just as he needs their support during the impeachment inquiry. Even a key ally of his tells me it’s a mortal threat to his presidency, after unnamed officials blew the whistle on his phone call with the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky. Tom Mueller, no relation to Bob Mueller, is a “New York Times” bestselling author who spent years studying the complex relationship between whistleblowers and society. His new book “Crisis of Conscience: Whistleblowing in an Age of Fraud ” is a timely reminder of the challenges and the personal cost to those who dare tell the truth. And he sits down with our Michel Martin to talk about what why this is ultimately about upholding American values.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN: Tom Mueller, thank you so much for joining us.

TOM MUELLER, AUTHOR, “CRISIS OF CONSCIENCE”: Thank you, Michel. It’s good to be here.

MARTIN: You say pretty early in the book that this is the age of the whistleblower. Starting in the late 1960s, this vital figure has emerged. And you say in the past five years alone people have disclosed the Cambridge Analytica, the use of Facebook data to help interfere with our shape elections, you’ve talked about, you know, the toxic levels of lead in Flint, Michigan’s drinking water, abuses and delays in the Veterans Administration Hospitals. I mean, it goes on and on and on. Why is this the age of the whistleblower in your view?

MUELLER: I think that our organizations, both public and private, have accepted or built a wall of secrecy around them and a wall of impunity around them, which leaves whistleblowers as the last line of defense. And the same time, regulators, investigative reporters and others who, in the past, had been this sort of — you know, the watchdogs have been sent home, euthanized, muzzled. And the internal people with a conscience, the people inside the organizations realize, I’m the last line of defense. If I don’t stand up and say something, no one will ever know.

MARTIN: Tell me about the case that opens the book of Allen Jones.

MUELLER: Allen Jones was an investigator at the inspector general of the State of Pennsylvania. And his job was to investigate fraud. He discovered that the state pharmacist was receiving checks from pharmaceutical companies and depositing them in an unmarked account. So, he started investigating more and he started questioning, why are these pharmaceutical companies paying this chief pharmacist? And the answer was, a multibillion fraud scheme across more than 20 states in which Johnson & Johnson and other pharmaceutical companies were corrupting the Medicare and Medicaid establishments in these states in order to push their antipsychotic drugs as the number one choice for a range of elements, many of which the FDA specifically said do not use on children, do not use on elders. First of all, his own office, the inspector general’s office in Pennsylvania treats him as a whistleblower and tells him, back off the case, Allen. These people are very power politically. Just treat it as an employment matter and move on. And he was not good with that. He’s out of a job now. He’s living in a cabin in the woods in Pennsylvania. He has only enough money for propane and only just that and spare tires for his truck. And he starts looking for somewhere to use this magical law, basically the False Claims Act. This law that allows you as an individual citizen to become a private attorney general. He finally finds it in Texas. He brings suit in Texas and he wins $166 million settlement against Johnson & Johnson. And later a $2.2 billion settlement is reached by the government against Johnson & Johnson. He wins on paper but Allen has told me, everyone that turned against me and all of the actual sufferers of the crime who didn’t get retribution didn’t get justice. He feels like the world really turned against him and that he finds it very difficult to trust anyone again.

MARTIN: There are those who think that whistleblowers come forward for the money because under the federal law, they get a percentage of the settlement, if there is one. Do you find that to be a motivation?

MUELLER: Allen Jones didn’t even know about the money until after he brought the lawsuit. And his lawyers told him, oh, by the way, there’s is a bounty in this, almost invariably. And then scholarship shows this very clearly. Whistleblowers go within their organization, first. They report it internally, they try to fix the problem. And their loyalty is to their greater organization. So often they say, I’m really proud of my bank or my hospital. I really want this to work and just I wanted to fix this the problem which would have made us look terrible. They don’t realize that their bosses are actually treating this as a feature and not a bug. I mean, the fraud is part of the model here. And only after they’re fired do they start saying, whoa, what just happened?

MARTIN: Most of these people experience like vicious retaliation. I mean, you’re talking about, you know, being stripped of your authorities, being put into offices next to the bathroom. Like, intentionally sort of humiliating. Tell me more about that.

MUELLER: There’s almost a playbook for how you retaliate against whistleblowers. And it goes through a serious of ritual humiliations that you do in public, in front of your coworkers. You know, you’re marched out by a security guard, you are ritually stripped of your security clearances, you are, again, placed downstairs in the basement next to a loud photocopier, you’re stripped of all of your — you know, your symbols of authority. And that tells you you’ve done horribly wrong but it also tells your officemates, anyone else who speaks up, this is going to be you next.

MARTIN: Why don’t they just fire them though? I mean, why do they go through all of that? Why don’t they say, I don’t like what you’re saying, you got to go? Why don’t they?

MUELLER: They need to send a message. They need to send a message to that person but also to every else, don’t speak up. Get with the program. And after they leave, quite often, they’re put under surveillance. What are they doing? And there are private investigators lurking around their houses. They get death threats at night. They get lawsuits, lap lawsuits. I mean, these can be devastating for people. But the kinds of retaliation we’re talking about, quite often, cause them to lose their marriages, lose their houses, they can’t work anymore. One of the most devastating things they’re blackballed in their organization and in their industries.

MARTIN: In their industry. Give an example of that, if you would.

MUELLER: Donna Bushy and Walt Tamasitis were two — are two extremely well prepared nuclear engineers. They helped to avert a potential massive nuclear disaster in Washington State. They did everything they could internally to raise the question because they were good, loyal employees and they thought this is, you know, my duty to my company, to help to prevent this. But ultimately, they said no, my real duty is to prevent a massive nuclear disaster. They did all the right things. They went through channels. Then they went outside channels. They went to the press. They filed lawsuits. And for their good offices, how are they thanked? They are ritually humiliated by their organization. They’re blackballed in the industry. They will never work again. What does that tell you about an industry that prides itself on protecting, you know, the U.S. population from nuclear disasters? That’s very disturbing to me.

MARTIN: And what was the stated reason at the institution gave for treating them that way?

MUELLER: Well, they were considered to be disgruntled employees or considered to be potential security risks because they questioned the messages of the organization.

MARTIN: Because they went to the press, ultimately?

MUELLER: Yes.

MARTIN: When internally their information was not received and acted upon, so they went to the press. They then became the enemy.

MUELLER: Precisely. Almost a spy. I mean, the nuclear industry is very definitely sealed under the cold war secrecy umbrella. But, you know, ultimately it challenged their bosses and they challenged their corporations.

MARTIN: As as we are speaking now, you know, the Trump administration, the president, in particular, is extremely upset about the people who raised questions about the phone call that he had with the president of Ukraine. I mean he’s used those words “spy”, “treason.” Some of the people around him have used those words. You were working on this book long before the administration took office. What is your reaction to the way the administration is responding to this information?

MUELLER: Well, Donald Trump and his allies are taking a page out of the whistleblower retaliation handbook. This is whistleblower 101 retaliation. You shift the attention of the general public from the message that this person is bringing forward. The facts in the nine page was a complaint that they brought to the messenger and questioned their motives, their loyalty, what are they actually doing? What is the deep state question? All of these things are distractions from the facts. What we need to do is refocus on what is in that document and what will that person say under testimony? What will the other 12 people he referenced in the document say when they’re called before Congress? This is a road map for finding out facts. No one is going to take their word for it. And ultimately we really don’t care what’s in their heart. We care what facts they deliver to Congress.

MARTIN: But what do you say to the Republicans, for example, who are now complaining about the lack of transparency? I mean, the Democrats are taking extraordinary steps to protect the identity of the whistleblower or whistleblowers. And they are — I mean this is necessary to protect both classified information and to protect these people from retaliation. Republicans are complaining bitterly that there’s a lack of transparency and due process and this is unfair. Based on your sort of deep dive into this topic, what do you say about that?

MUELLER: Well, first of all, the law guarantees anonymity. This person came forward on unguaranteed of anonymity. So this whole, you know, meet me in the OK corral, I demand to know my accusers. That’s whole rhetoric. That’s really asking people to break the law. And second of all, it’s absolutely fundamental to protect this person’s identity. Because we’ve heard what Trump himself have said. You know, back in the old days, we used to know how to deal with spies. So I would be very very worried as this anonymous whistleblower to have my cover blown. And when we have Republican senators saying this is illegitimate, I will out them. This is an extraordinary — this flies in the face of the law. This is illegality. This person was guaranteed an anonymity and they should have it for very very good reasons that have to do with their safety.

MARTIN: What about the Obama administration? I mean you never heard the Obama administration like trashing whistleblowers in public. But you make the case in your book that they were — what would be the word you’d used? Sort of equally disdainful of whistleblowers and, in fact, tried to retaliate against them. Talk about that if you would.

MUELLER: I would use the word punitive. And particularly in the national security space. One of the critical promises that Obama made was government transparency. And he was quite supportive on the corporate whistleblower front. When it comes to whistleblowers within the government, however, Obama has – – will go down in history as one of the worst administrations ever.

MARTIN: Tell me why you say that?

MUELLER: Because, his DOJ created the tools that now Trump is using to go after whistleblowers and after journalists who take whistleblower information.

MARTIN: Tell me more about that.

MUELLER: Well, this is absolutely critical to know that when you bring classified information to the press, you are breaking a law. Okay. And you’re breaking regulations within your organization, whether CIA or NSA. But the public, the public interest is a balancing act. If you are bringing — if you’re Daniel Ellsberg and you’re bringing out the Pentagon papers which are top secret but you helped stop the Vietnam War, you have just done an enormous service to the American public. Today in court, as a whistleblower under the Espionage Act, you cannot talk about public defense. There’s no public defense motivation that you can bring up that says, look, I did what I did because I wanted to save the American public from a war, from being spied on, from being a party to torture, to being a party to black operations and abduction of individuals. All of these things have really brought our country to a terrible place. Well, guess what, George W. Bush and company founded those things but then Obama and his department of justice normalized them. And when he went after — he and Eric Holder and the department of justice, went after national security whistleblowers, they went after it with an extraordinary venom and extraordinary blunt force of the Espionage Act which is a 1917 act for spies.

MARTIN: And when you say that, what do you mean? You mean going after reporters, trying to prosecute reporters? Is that what you mean?

MUELLER: That’s the knock on effect. Well, first of all, we’re going to put these people in jail for doing things.

MARTIN: But did they actually put people in jail? That is the question.

MUELLER: Absolutely. Yes, absolutely. I mean, Jeffrey Sterling, John Kiriakou. We’re talking about people who reported gross fraud and abuse. We’re talking about people who reported torture. We’re talking about — you know, Reality Winner, she’s in jail now. These are very very important issues. Not to be able to explain why you did what you did to the court of law is for me, one of the ultimate injustices.

MARTIN: But couldn’t the argument — would the argument be that whistleblowers are trying to contravene policy. They’re unelected and that they’re trying to contravene policies made and implemented by elected officials. You’ve cite the example of the Vietnam War but the Vietnam War had a very deep stem. It was not sort of an act of wrongdoing by one individual. It was a collective decision under taken by elected policy holders who are accountable to the public in that way. So what do you say to those who argue, as I think the Trump administration is now, that these are unelected individuals who are trying to contravene the policy imparities of people who were elected? What do you say?

MUELLER: The national security was supposed to bringing forward issues that are fundamental to our republic, fundamental to our democracy. We’re talking about warrantless wiretapping. We’re talking about are we good with torture, are we good with illegal wars? Are we good with drone war affair? These are issues that are not just a matter of policy. They’re a matter that these whistleblowers say the American public should be deciding about this, the American public has a right to know about this. I can see my administration. No administration is going to bring this up. We’re not going to confront this. I need for the American public to know.

MARTIN: So like Edward Snowden, the warrantless surveillance strategies.

MUELLER: Precisely. Precisely.

MARTIN: I mean the fact is we also have a tradition of civil disobedience in this country. But part of that traditional civil disobedience is you subject yourself to the whatever the society deems appropriate even if it’s punitive in order to make your case. I mean that’s what Martin Luther King did. That’s what other people who have engaged in civil disobedience have done. Should he come back and subject himself to a process by which the public can judge whether he was right or wrong?

MUELLER: Right now, Edward Snowden coming back will not get a fair trial. He will be tried under a 1917 draconian Espionage Act which has one purpose, to shut people down and to eliminate discourse about critical matters of our democracy.

MARTIN: In your reporting, whistleblowers generally don’t have a political motivation, per se. They have what, an orientation toward the public good as they understand it?

MUELLER: These are people who really believe in the public good. And they see past the can’t of their organization, whether it’s a government agency or a private company and say I’m serving the American public here. Again, it’s sort of an old fashioned concept. When you say it’s old fashioned, it tells you how far we have drifted from the original American values. One of my whistleblowers said, we just forgotten how to be Americans. We need to remember a little bit about how to be Americans.

MARTIN: Tom Mueller, thank you so much for talking to us.

MUELLER: Thank you very much, Michel.

About This Episode EXPAND

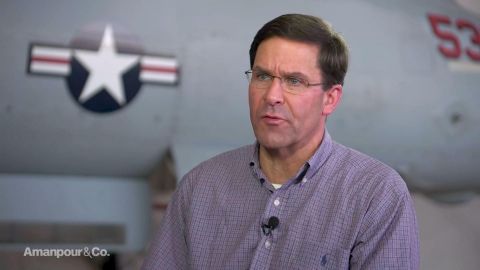

In an exclusive interview, Christiane Amanpour speaks to U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper in Saudi Arabia as thousands of new U.S. troops are deployed to the country to try and visibly confront Iran. Plus, Michel Martin speaks to Tom Mueller about the complex relationship between whistleblowers and society, and Walter Isaacson speaks to Richard Stengel about his new book “Information Wars.”

LEARN MORE