Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now we turn to a controversial new app threatening to weaponize profiling like we have never seen before. Clearview AI is a ground-breaking facial recognition technology that scrapes billions of images from social media and all across the Internet. It is currently used by the FBI and hundreds of law enforcement agencies in the United States and Canada to identify suspects. Hoan Ton-That is the founder and CEO of Clearview. And our Hari Sreenivasan asked him what the company can do to keep law enforcement and other users from abusing this powerful new tool.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN: So, let’s start with the basics. How does automated facial recognition work?

HOAN TON-THAT, FOUNDER AND CEO, CLEARVIEW AI: This is — what we do at Clearview is actually not automated facial recognition.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

TON-THAT: We’re an investigative tool for after-the-fact investigations. So, after someone has committed a crime, there’s probable cause, for example, a bank robbery, then a detective can use our tool, take a photo of that face, and then perhaps have a lead into who that person is, and as a beginning of an investigation, not the end.

SREENIVASAN: So let’s say you get a picture of a bank robber. How is the software working? How does it find that face in a sea of faces?

TON-THAT: What happens is, the investigator will find a right screencap of the right frame, and then run the app, take a photo, and it searches only publicly available information on the Internet, and then provides links. So, it just looks like and feels like Google, but you put in faces, instead of words.

SREENIVASAN: OK. So how does it know my face is different than yours, when we actually — in sort of computer-speak, what is it looking for? What are the similarities, what are the differences that make our faces distinct?

TON-THAT: Yes. So, the older facial recognition systems, because facial rec has been around for 20 years…

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TON-THAT: … were a lot more hard-coded. They would try and measure the distance between the eyes or eyes or nose. And what the next generation of artificial intelligence has allowed is a thing called neural networks, where you get 1,000 faces of the same person, different angles, or with a beard, without a beard, with glasses, without glasses. And the algorithm will learn what features stay the same and what features are different. So, with a lot of training data, you can get accuracy that’s better than the human eye.

SREENIVASAN: So, training data means what, more samples?

TON-THAT: Yes, more samples.

SREENIVASAN: So, the larger the sample set, the better the software gets?

TON-THAT: Exactly.

SREENIVASAN: And how big is a sample set that you’re working with now?

TON-THAT: So, we have a database now of over three billion photos.

SREENIVASAN: Three billion photos?

TON-THAT: Yes, correct.

SREENIVASAN: Where did you get three billion photos from?

TON-THAT: They’re actually all over the Internet. So you have news sites, you have mug shot sites, you have social media sites. You have all kinds of information that’s publicly available on the Internet. And we’re able to index it and search it and use it for — to help law enforcement solve crimes.

SREENIVASAN: OK. So let’s see a demo of how this works. I’m going to try to show you some photos. And these are photos that we have permission from a couple of the people. We’re probably going to shield their faces. Now let’s try a blurry picture.

TON-THAT: OK.

SREENIVASAN: I don’t know if this will work or not. But, a lot of times, a police officer is not going to work with a beautiful, perfectly in-focus shot, right?

TON-THAT: True. And one thing to keep in mind, the way the software is used and the protocols that law enforcement is only — you can only run a search if a crime has happened.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: And, two, this is not sole-source evidence. You have to back it up with other things. So it’s a beginning of an investigation.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

TON-THAT: So, I have never tried this before. And it’s a little blurry, but taking a photo of a photo.

SREENIVASAN: And now it’s searching all three billion photos at the same time?

TON-THAT: Yes. So, it might actually, because it’s blurry, find other blurry photos. But it looks like we do have one match there on Instagram. You can click on it, and you can see…

SREENIVASAN: If that’s the same person or not?

TON-THAT: Yes. So, it looks like that’s the actual same photo that we found.

SREENIVASAN: And, in fact, that is the same photo that we found.

TON-THAT: Exactly. So that’s how…

SREENIVASAN: So that was posted on Instagram. And your software had that photo in its corpus of three billion photos?

TON-THAT: Correct.

SREENIVASAN: And is that because that that account was public?

TON-THAT: Yes. So, it’s a — it was a public account, and that photo was posted publicly.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

TON-THAT: So, if the — if law enforcement is investigating an actual crime — now, it’s not a crime to be at a protest, of course.

SREENIVASAN: That’s right.

TON-THAT: And there are concerns about how the technology is used. And that’s why we have controls in place, and that’s why we want to be responsible facial recognition. This is just an example.

SREENIVASAN: Sure. And let’s try somebody who says that she keeps herself pretty limited to social media. Let’s try that face.

TON-THAT: So, again, a photo of a photo, just for demonstration purposes.

SREENIVASAN: And that is the same woman. So, this — these three billion images that you have got in the system here, pretty much every major tech platform has told you to cease and desist, stop scouring our pages.

TON-THAT: Mm-hmm.

SREENIVASAN: What does that mean to the three billion image set?

TON-THAT: So, first of all, these tech companies are only a small portion of the millions and millions of Web sites available on the Internet. So we have received cease-and-desists from some of the tech companies, and our lawyers are handling it appropriately. But one thing to note is, all the information we are getting is publicly available. It’s in the public domain. So we’re a search engine, just like Google. We’re only looking at publicly available pages, and then indexing them into our database.

SREENIVASAN: So, how many police departments are using this now?

TON-THAT: We have over 600 police departments in the U.S. and Canada using Clearview.

SREENIVASAN: And when you say using, that means that they are running this, they — their officers have them in hand? How does it work?

TON-THAT: So, typically, it goes to the investigators doing crimes. And they might have a different number of people using it to solve cases.

SREENIVASAN: Do you have the equivalent of like a God View that can see what every department and every investigator is searching for?

TON-THAT: So, what we have done is, we have an audit trail from each department. So, say you’re the sergeant or you’re the supervisor in charge. You can see the search history of people in your department to make sure they’re using it for the proper cases, so they’re not using it to look people up at a protest. You need to check that they have a case number for every search that they have done and things like that, yes.

SREENIVASAN: So, who is policing the police?

TON-THAT: So, they have procedures in place about how you’re meant to use facial recognition. So, some of these departments have had it for over 10 years, procedures in place on how to properly do a search and all the guidelines and they — and so on. So they, I feel, have pretty good procedures in place. And police are some of the most monitored people in all of society. So, you know, they don’t want to make a mistake, and we don’t want them to have any abuse. So, we’re building tools for the police department, and we’re adding more things to make it secure for them.

SREENIVASAN: How do I know how many bad guys the cops have gotten using this vs., for example, the number of good people that it might have wrongly identified?

TON-THAT: Yes, that’s great. So, I think the history of our tool, we haven’t had anyone wrongfully arrested or wrongfully detained with facial recognition at all. On the flip side, all the cases that are being solved — we get e-mails daily. I got one two days ago that said that these — highway patrol could run a photo of someone they couldn’t identify, that he was picking up three kilos of fentanyl. So, we get e-mails like that every single day from law enforcement. So we really think that the upside is completely outweighing the downside. I understand that there are a lot of concerns about misuse and all that stuff. But, so far, they have all been hypothetical and misidentification. So our software is so accurate now, as you can see in the demo — and we made sure it works on all different races and all different genders — and it’s also not used as evidence in court.

SREENIVASAN: One of the things that you said interested me. How do you make sure that the software is able to find distinctions in people of color or by gender?

TON-THAT: Mm-hmm. So, one thing our software does is, it does not measure race and it does not measure gender. All it measures is the uniqueness of your face. And when you have all this training data that we have used to build the algorithm, we made sure that we had enough of each demographic in there. So, other algorithms might be biased in terms of not having the minorities, enough training data in the database for them. So, that’s something we made very sure of. And we have done independent testing to verify that we are not biased and have no false positives across all races.

SREENIVASAN: You’re Vietnamese-Australian, right? But you have been in the United States for a few years. And I have just got to ask, have you ever been stopped and frisked?

TON-THAT: No, not yet.

SREENIVASAN: Right? I mean, do you know what that is — why that’s so important in the United States, why people have this feeling that, even if there are 99.9 percent the police are out to protect us, they’re doing a great job, there have been so many encounters with police, for — certainly for people of color, where they feel like, I don’t need one more tool where it will be used against me on the streets of New York or some other city, right?

TON-THAT: Absolutely. So, we’re — again, we’re not real-time surveillance. We’re an investigative tool after the fact. And, yes, stop and frisk was definitely too aggressive for what the benefits were for — it was for. And I think, with our kind of tool, we would be able to even decrease that kind of behavior amongst the police. If you’re just profiling people based on the color of their skin, you know, that’s not a fair thing. And I think that’s why there was such a backlash against stop and frisk, because people of color were just totally innocent, getting stopped and frisked all the time. Now, maybe in a different world, with — you could be a lot better with accurate facial recognition.

SREENIVASAN: But here’s the thing. At this point, I’m a 14-year-old boy of color walking down the street. A police officer now has your app, also puts my face into the system. Over time, the next time I have a photo of me taken for any reason, now here’s a track record of one more photo that’s been taken by a police officer. Is there something suspect of this child, right? I mean, that’s one of the ways that people fear that these technologies will be used against us.

TON-THAT: Yes. So, right now, just to be clear, this is used as an investigative tool. So, people aren’t out there just taking photos in the wild.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: Some crime has happened, there’s probable cause, et cetera. And…

SREENIVASAN: That’s your intent.

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: That’s the intent of your company today, right?

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: But the technology is what the technology is.

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: If someone else had access to this tool, couldn’t it be used in a different way?

TON-THAT: Yes, that’s why we have a lot of policies in place. But, also, technology is not done for its own sake. It’s always run by people, right? We have a company. We have very strong beliefs in how it should be used, and so does society. And we don’t want to have anything that’s too conflicting, or we don’t want to create a world we don’t want to live in personally. So, yes, maybe someone else could build something similar and use it — misuse it for other things, but that’s not what we’re going to do.

SREENIVASAN: So how do I have that assurance? Look, you’re a smart guy. There’s lots of tools that have existed on the planet, like, you could say cars or guns, right? They’re — it depends on who is driving them and how they’re used. And we have tons of regulations and laws and safety measures in place. And even with that, we have thousands of people that die in car accidents, and then we have mass shootings. On the — the edge cases are very, very bad, right?

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: And that’s with lots of guardrails in place. In this arena, there’s no legislation.

TON-THAT: Well, listen, we’re actually for regulation in a lot of ways. We think it is a powerful tool. I think the right — the public has a right to know how it’s being used currently. That’s why we’re here and talking to everybody. But I also think that federal guidelines on how it’s being used would be a — probably a very positive thing. It would put the public at ease and it would — law enforcement would understand, this is how you use it, this is how you don’t use it. And I think the choice now is not between, like, no facial recognition and facial recognition. It’s between bad facial recognition and responsible facial recognition. And we want to be in the responsible category.

SREENIVASAN: You’re also trying to take this business global. It’s not just police departments here, but there have been maps in some of your literature that says that you’re selling it overseas. Is that true, right?

TON-THAT: So we’re actually focused on the U.S. and Canada. But we have had a ton of interest from all our around the world. So, what is interesting is, as the world’s more interconnected, a lot of crime is also global. But we’re very much focused on the U.S. and Canada. And it’s just the interest from around the world is just a sign that it’s such a human need to be safe.

SREENIVASAN: But, inevitably, as you just said, the rationale for having it overseas is that crime knows no borders, right?

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: And that you want to help law enforcement authorities all over catch bad guys. But those other countries might have different value systems.

TON-THAT: Sure. I — there’s some countries that we would never sell to are very adverse to the U.S.

SREENIVASAN: For example?

TON-THAT: Like China, and Russia, Iran, North Korea. So, those are the things that are definitely off the table. And…

SREENIVASAN: What about countries that think that being gay should be illegal, it’s a crime?

TON-THAT: So, like I said, we want to make sure that we do everything correctly, mainly focus on the U.S. and Canada. And the interest has been overwhelming, to be honest…

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: … just so much interest, that we’re taking it one day at a time.

SREENIVASAN: You also said something like you don’t want to design a world that you don’t want to live in.

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: What does that world look like, just so I know?

TON-THAT: Great. So, I think that your private data and your private thoughts, your private e-mails, they should stay private, right? I don’t think that it’s — unless you have very, very rare cases around national security, which is what the FISA courts are for, surveillance into everyone’s private messages — I don’t think that’s the right thing. But I do think that it’s fair game to help law enforcement solve crimes from publicly available data.

SREENIVASAN: You know, we have had — post sort of the Edward Snowden revelations, we have plenty of evidence of our own government overstepping the bounds. What if your software facilitates a world you didn’t want to live in?

TON-THAT: Well, we’re not going — we make sure that won’t happen. But, to be clear, like…

SREENIVASAN: Look, do you think Mark Zuckerberg thought that his software would be manipulated in an election? No.

TON-THAT: Of course he didn’t.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: But I think Facebook provides the world a lot of good. It connects a lot of people…

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: … that otherwise wouldn’t have been connected. Tons of people have gotten married through Facebook. And I think the benefit of it outweighs the downside.

SREENIVASAN: Again, it’s a platform.

TON-THAT: It’s a platform.

(CROSSTALK)

SREENIVASAN: It’s a — right? But what I’m saying today is, is that are you planning today, are you figuring out, what are the edge cases, and how do I insulate myself against the worst thing that could happen?

TON-THAT: Exactly.

SREENIVASAN: Because it seems like, if you can design something, there’s someone out there very smart trying to figure out, how can I abuse his tool?

TON-THAT: Exactly. We always think of the edge cases. That’s where we want to go with everything, when you think about risk mitigation. So, like you said, cars, very regulated, but you can take a car and drive it into a building. Very rarely happens. Same with guns. There’s more controls over guns, and school shootings and shootings are very unfortunate to have in this country. And we have actually helped with some of these active-shooter cases. That’s pretty interesting.

But with this tool, it’s — you know, what’s the worst that can happen with it? It’s — we always think about that and how to mitigate that and make sure that only the right people are using it, and that the more sunlight you show on the use of the tool, and the more controls for law enforcement — so maybe someone doing too many searches of the same person or — there are more things we can add to our system. And that’s why we’re excited to start the debate or, like, learn more from people in government about what is the right thing to do.

SREENIVASAN: There’s a certain level of obscurity, almost, that feels part of being human, that I interact differently with you than I do with my family, than I do with my colleagues. Right? So, I guess it’s kind of a philosophical question, but do I own my face anymore?

TON-THAT: It’s your face. Of course you do. But, like, what you’re talking about is more like social context in who you’re hanging out with, et cetera.

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: So…

SREENIVASAN: I mean, context starts to dissolve if it’s really up to your search. Right? Your search, if you did my face right now, which you can do, there’s going to be hundreds and thousands of pictures of me probably doing television shows and whatever. There might be some with my family. There might be some with whatever. It’s all — there’s no context. It’s just all one set of images.

TON-THAT: Yes, exactly. And I agree with you. Like, this tool should be used in the right context. And that’s why we found law enforcement was by far the best and highest purpose in use of facial recognition technology. Now, on the flip side, like you said, if I had this app and I saw you on the street and I ran your photo…

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TON-THAT: … and I could ask you questions and know a lot about you, I don’t think that’s a world I want to live in either.

SREENIVASAN: How do you ensure that whoever takes over your company when you move on to the next thing lives by these same values?

TON-THAT: So, for us, it’s about the company culture, what we believe in, but, also, the real value and the thing I get excited about every day is the physic value from all the great case studies we have and all the crimes we help solve. So, that’s what we’re really in for it. We’re not really in for it for the money. And other people have said, maybe you should do a consumer — it’s a bigger market. Many venture capitalists have said, law enforcement is a small market. Why don’t you do something else? But we really believe in the mission, and we believe the value to society is so much higher if we do it in a responsible way.

SREENIVASAN: Do you control the bulk of your company, similar to what lots of tech company heads have done, meaning you have more voting shares, like the Google guys or Mark Zuckerberg or anything else? Let’s say at some point your investors outvote you and say, we really should be looking at the bigger picture here, because we can make more money, we’ve invested this for a return? They’re not in it for the psychic value. They’re in it for the dollars.

TON-THAT: I think investors have both motivations. You can’t say they’re always in it for the money. And we try and pick investors that are very much aligned with the mission. That’s why the ones who wanted us to be consumer, we rejected. And the ones who really believe in law enforcement and law and order, we worked with. And, for now, we do control the vision and the direction of the company. And you got to understand, businesses are here to make money, and that’s a good thing. But it’s more important to provide value to society. And I think we’re doing that at a really big level.

SREENIVASAN: Who are the big investors, or how many investors do you have, or what part of that information do you share?

TON-THAT: We have — we have done two rounds so far of investment, a seed round and a Series A. And we don’t really talk about our investors.

SREENIVASAN: So here’s the thing. It’s like, I want to believe the fact that you want to pick investors that are mission-driven, right? But if you don’t know who those are, that doesn’t look like a lot of transparency either.

TON-THAT: Yes, they just don’t want to be named at this point.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: And we want to protect their privacy. That’s important to us.

SREENIVASAN: That sounds the most ironic, because…

TON-THAT: OK. Sure. I know.

(LAUGHTER)

SREENIVASAN: Right? It’s like I get that you want to protect their privacy, but everybody is looking at this app, saying, well, what about our privacy? What about the three billion images that exist out there?

TON-THAT: We have Peter Thiel as one of the investors involved, Naval Ravikant.

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: We have a whole wide range of investors. And we’re thrilled to work with them. We love their support. They’re all U.S.-based or U.K.-based. And that is important to us to make sure it’s in the hands of American investors.

SREENIVASAN: Hoan Ton-That, thanks so much for joining us.

TON-THAT: Thank you very much. Appreciate it.

About This Episode EXPAND

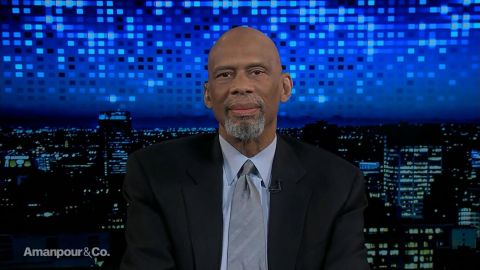

David Miliband, president of the International Rescue Committee, gives an update on the humanitarian crisis in Idlib, Syria. Basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar tells Christiane the stories of black patriots overlooked in U.S. history. Hoan Ton-That, the founder and CEO of Clearview AI, joins Hari Sreenivasan for a conversation on the societal implications of facial-recognition technology.

LEARN MORE