Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: The earth is on fire.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Voters are calling for climate action. Are corporations finally doing their bit to tackle the crisis? I speak to Unilever’s former CEO,

Paul Polman, in this climate special. Then, why governments must also step up and be part of the solution. The man who helped sound the alarm, Bill

McKibben, joins us.

Plus —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ROBERT BULLARD, AUTHOR AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCHOLAR: Climate change, sea level rise, will exacerbate the inequities that already exist.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The father of environmental justice, Robert Bullard, on the burden of climate change on minority communities.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Millions of voters have been casting their ballots this Super Tuesday across the United States, as the Democrats ramp up their contest to take on

President Trump in November. And for the first time, one of the top issues is the climate crisis. Two-thirds of Americans say the federal government

is not doing enough to tackle it.

In our program tonight, we want to look not just at the politics, but also at the people offering solutions, the people re-imagining the system. An

increasing number of corporations are stepping up to the challenge, putting them a step ahead of their governments.

This year, we’ve seen climate pledges from some of the largest and most profitable companies in the world. Microsoft, Amazon, Nestle and Shell to

name a few. They are all promising to reduce their carbon emissions.

Now, for more than a decade, Paul Polman, was CEO of the consumer products giant, Unilever, whose brands include Ben and Jerry’s, Dove, Hellmann’s and

Vaseline. He believes capitalism must adapt to climate change and he’s always dared to do things differently, increasing Unilever’s positive

social impact and its profits. And he joined me in Florida to talk climate and corporations.

Paul Polman, welcome to the program.

PAUL POLMAN, FORMER CEO, UNILEVER: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: So, listen, we wanted to ask you, because — I mean, everybody knows that you’ve been ahead of the curve on responsible capitalism,

sustainable business, and I just wanted to ask you just in the first instance, why do you think we are suddenly almost all of a sudden in a

short period of time hearing from a lot of very serious CEOs of a lot of very big corporations that they suddenly have plans to get sustainably

responsible and to sort of kind of change at least some of their business practices? What do you read into that?

POLMAN: Well, indeed, Christiane, we’re seeing a momentum picking up in terms of the private sector taking climate action and I think the main

reason first and foremost is it’s an economic issue. We have — on the one hand, we are more aware of the enormous costs by not tackling climate

change, which is increasingly going up. And on the other hand, we’ve seen technology develop at an enormous speed.

If you look at solar or wind, these costs have come down in the last seven, eight years alone by 70 percent, 80 percent. The same for hydrogen. So, on

the one hand, enormous precious on costs, on the other hand, opportunities. And then the third factor, if I may add to that, is really pressure,

pressure from civil society, pressure from their own employees, increasingly pressure from the financial market that these business models

need to change to stay relevant for the future.

And it is not surprising now that we see about 25 percent of the global GDP in business terms aligning themselves behind climate action.

AMANPOUR: So, I just want to step back a little bit and talk about your own experience at Unilever, where you, you know, were CEO and they’re just

so many of the world’s most well-known and popular brands. And you did say, at one point, that you were seeking a team of heroic chief executives.

That’s what — that’s how you put it, to try to move this conversation and these corporate practices along.

Tell me about what you went through. Because I think you also said that, you know, when you started this you were kind of ridiculed or looked at if

you were a little bit of an outlier. What was your evolution?

POLMAN: Ten years ago when we started the journey in Unilever and said we have to decouple growth from environmental impact, increase our overall

social impact, it was a relatively new concept. Put yourself now 10 years further where we are today, we have indeed increasing evidence and proof,

hard numbers, that business models that are run for the longer-term take the multiple stakeholders into account.

One of the stakeholders being our planet itself. That these business models tend to be better longer-term for the shareholders as well. In the case of

Unilever, that meant about a 300 percent shareholder return over the 10 years and a growth level, a turnover growth that was twice the level of the

industry. So, these models tend to be more profitable and also for the shareholder longer-term.

When I started the journey, these data were there. A lot of cynicism or skepticism by an increasingly shorter-term focused financial market

especially, that why are you hanging around the U.N., why wouldn’t you worry about de-forestation.

It was a little bit of an act of faith and a commitment driven by a deeper sense of purpose. Now, we’re being aided by the hard facts. Companies that

can attract employees who want to work for mor purpose driven companies can attract better employees tend to do better. Companies that are more diverse

in terms of gender balance tend to do better. Companies that internalize now the challenges of climate change, which we’re talking, tend to do

better.

AMANPOUR: And I think you talked also about CEOs, certainly in your experience, having to move beyond your comfort zones. You’ve just explained

that you have to break out of this sort of traditional view of what is profitable or what is the kind of corporate capitalism that’s been

traditionally practiced.

You’ve also, I think, said, and certainly others have said, that potentially the examples set by some of these corporations could start “a

race to the top.” We understand that some 100 companies in the world are responsible for about 71 percent of all carbon emissions. Do you see kind

of, I guess, sort of peer pressure, to put it another way? Do you see that working in the executive suite, in corporate — at the top of the corporate

pinnacle?

POLMAN: Well, it definitely does. If you now look at it nearly on a weekly basis, on a daily basis, you get announcements from Amazon, from Microsoft,

from Delta Airlines and then Europe, companies like Sainsburys and many others that are known, Nestle, all making commitments over a billion, $2

billion. So, there is something out there that I think is resulting in bigger action.

We see on the one hand companies taking care of their own shop and trying to move very quickly to green energy, partly driven again by the economic

forces. But we also see them taking more and more responsibility of the value chain and really looking at their sourcing, for example, are we

having de-forestation or not, can we get coal out of the value chain. So, this race to make your business models more robust, better fit for the

future, is definitely happening.

And as a result, you can also see in the industry reflected in financial performance where the winners and the losers are.

AMANPOUR: What would you say to those who will say, well, it’s all very well for Paul Polman of Unilever or BP or BlackRock or any number of the

big behemoths to talk like this and take these risks? But what about the, you know, much smaller companies? What about the much poorer, you know,

businesses? Can they afford to do what’s necessary to also be sustainable?

AMANPOUR: Well, yes, the premise, Christiane, is that in order to be sustainable, you have to invest and compromise short-term profit. That

might be the case for some things. But if you put yourself on a five or 10- year timeline, I think you can manage that. We have now come past what I would call the tipping point where we actually can show also to the smaller

companies that if you are actively involved, you equally get economic benefits and a more motivated workforce, you get more relevant products,

you actually get lower cost.

So, these tradeoffs that historically might have been there between doing the right thing and having a financial performance that is solid is

increasingly less. Smaller companies have the benefit of being more agile. For a company like Unilever or BlackRock to de-carbonize their total

portfolio or to get to green energy in the total value chain is not an easy thing.

If you’re a smaller company, you tend to have access to sustainable-sourced materials or green energy in a better and faster way than many of the big

companies. And as a result, we actually see these smaller companies moving faster. The U.N. global compact has 13,000 companies, many of them the

smaller SMEs, and they are moving very fast on climate change.

AMANPOUR: So, Paul Polman, we’ve already talked about the pressure of the street, in other words, people. People have changed this. People have

caused this shift. People — I know you admire Greta Thunberg. She’s obviously trolled and vilified in other parts, including President Trump.

And I mention this because the United States is responsible for 15 percent of global emissions, China for 27 percent of global emissions, neither is

successfully curbing their emissions. And additionally, the United States is, you know, rolling back all sorts of regulation, messing with the

science, inserting all sorts of, you know, non-evidentiary language into their policy papers.

Do you think that business and these big corporate titans that we’ve been talking about, especially American ones, can and will influence the

government?

POLMAN: Yes, this is a very important question, Christiane, and I’m glad you’re asking it. There is no doubt that we can bend the curve with a lot

of the efforts by individual citizens of this world or by corporations. But to truly tackle the issue of climate change and stay below the 1.5 degrees,

which is by all means possible, we indeed need the governments.

The good thing is that we have about 120 governments in the world, including the Europeans, with the Green Deal, the U.K. government that have

made commitments to be by what we call net zero by 2050. It is some of the bigger countries like China, like the U.S., like Brazil now that are

trailing and frankly holding the system back.

A result of a little bit not addressing the issues in the first place, which has created populism and nationalism at national lever for which we,

to some extent, are paying the price. I do want to point out though that in the U.S. itself, about 75 percent of the U.S. economy has put themselves

behind climate action.

There are major movements in this country that we are still in movement, the America pledge movement, where you see at the sub-national level, state

level, city level, but also obviously with corporations, this country is moving, and actually is moving a little bit ahead of the Paris agreements.

Likewise, with China, you see China moving fast, but they obviously have a challenge of still having the economic growth curve to make the country

function in the way that they have designed it to be. But in their 14th (ph) 5-year plan, you see major efforts. When 80 percent of your land is

degraded, your water is polluted, your air pollution which globally kills 8 million people prematurely, far more than the coronavirus, then their alarm

bells ring and countries start to go into overdrive.

AMANPOUR: You’ve made some very interesting points about how the sub- national level is doing pretty well in the United States. So, it’s interesting to hear what you’re saying. But you’ve also talked about —

POLMAN: Yes.

AMANPOUR: What makes you think or do you think that the big fossil fuel industries are really going to do their bit? Because yes, they’ve pledged a

lot, and yes, they’ve said — spent a huge amount of money saying they’re going to do this, that and the other. But on the other hand, they have also

spent nearly $200 million a year lobbying to delay, control, block policies that tackle climate change.

And, you know, in 2019, their spending on oil and gas were increased to about $115 billion of that. So, again, there seems to be, at least in that

industry, which is the most important one when it comes to carbon emissions, there seems to be a little bit of trying to have your cake and

eat it too.

POLMAN: You are talking about the heavy emitting companies and they are all included in the 100 that do the 71 percent of the emissions that you

alluded to. We only have about 10 percent of these companies making firm commitments to stay below 1.5 degrees. So, by any means we have our job cut

out still.

And while we see momentum, it is relative, we really need to accelerate it. So, I don’t disagree with you. It is a transparent world now and the

citizens of this world don’t accept that any longer and I think companies’ trust and credibility will be undermined if you don’t have a consistent

policy.

The good news now is that in the major oil sector that you are referring to most of them are calling for a price on carbon, that’s actually driven

perhaps initially to not be — not have to compete with coal. I think that is perfectly valuable. The externalities of coal are simply too high, we

cannot afford it anymore. But increasingly, you see also the oil companies here looking at carbon dividend systems or carbon tech systems that

hopefully transition this industry faster.

There is no doubt, though, that if you are in the carbon industry, that you need transition. To turn off the switch of an industry that has helped us

develop the world to where we are and brought a lot of energy needs to be done with thought and needs to be done over a certain period of time. But I

personally believe that the pressures of the oil industry to move faster, to be more consistent between what they say and what they do will only

increase. And I agree with you in this respect that we still have some way to go there.

Coming back to your previous question, Christiane, very quickly, I think we’re at the moment now that we are building more of a critical mass of

bigger companies, that are actually moving, that are willing to show how to achieve decarbonization and actually are giving increasing confidence to

the governments.

2020 is a very important year for the governments of this world, where in the COP26 in Glasgow at the end of the year, they have to come in with

higher ambitions versus the Paris agreements that were done five years ago. And right now, we see many of these countries sitting on the fence, not

willing to come out. A little bit of uncertainty about the global economic situation, the coronavirus not helping, looking at other countries moving

fast. There is little movement, and that is obviously of concern.

We are now looking at a high ambition coalition of companies that actually in each of the countries are saying, hey, we in the private sector are

already ahead of where you are in the public sector. Be more ambitious, be more courageous, because this is actually the growth story of the century

and it will help unlock some of the economic growth that we’re all desperately looking for.

AMANPOUR: The growth story of the century. That’s really interesting. Well, you put your money where your mouth is throughout your career. So, I

want to ask you just finally then, you know, you have called capitalism a damaged ideology. And yet, there are many people who think that, you know,

climate mitigation could, you know, affect growth. You’re saying no, it could actually spur growth. Some people say, no, it’s going to cause a

recession. That is what some people actually say, as you know.

What do you mean by damaged ideology and how would you fix the ideology of capitalism?

POLMAN: I think capitalism needs to move to multi-stakeholder capitalism or more moral capitalism. I don’t want to debate the wealth capitalism

itself, but we are now in the United States where I am actually working some of the issues.

And I just refer back to the history here when you had Franklin Roosevelt who produced a new deal. This is a country that is being heralded as the

example of capitalism. But yet, at the time of the new deal, he bent the curve by introducing social security, by introducing health care and some

other things that created a period of wealth for this great country. And the same is needed now again.

There is no question that for this world to function, we cannot have these little islands of prosperity in an increasing larger sea of poverty. We

have to bend the curve of capitalism to make it more inclusive, to make it more equitable and to make it more sustainable. And that is by all means

possible.

We have 193 countries who in September 2015 at the United Nations agreed on what is called a sustainable development goals, 17 wonderful goals that

actually don’t leave anybody behind and create this more equitable, sustainable future.

And here again, what we are discovering, perhaps because we’ve waited so long to address these issues, that this is probably the biggest economic

opportunity. If you just look at conflict prevention and wars in this world, we spent 8 to 10 percent of the global GDP on dealing with this,

many of the issues go back to climate change or inequality. And by just spending one-third of that amount of money, we can actually avoid the bulk

of these issues.

AMANPOUR: All right.

POLMAN: So, I don’t think we have the right still to call ourselves the most intelligent species until we really get through this and actively

solve it. And it is an issue of will power. Do we really care as a collective humanity that planet earth, which is one of the stakeholders,

doesn’t have boundaries, and it is time that we get into more collective action to attack these issues and we all will be better off for it?

AMANPOUR: All right. Well, that is a really good and optimistic and solutions-full conversation.

Paul Polman, thank you very much indeed.

POLMAN: Thank you, Christiane. Appreciate it.

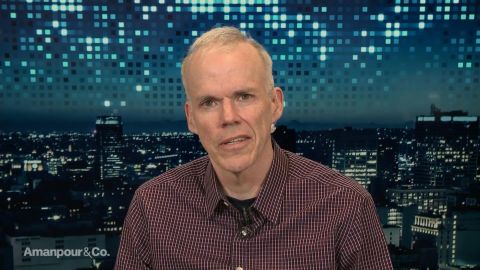

AMANPOUR: And next, to the grassroots battle. Environmentalist, Bill McKibben, has been at the forefront of climate activism for decades. This

week he launched a climate crisis newsletter for “The New Yorker” and he’s joining us from Vermont.

Bill McKibben, welcome back to the program.

BILL MCKIBBEN, ENVIRONMENTALIST: Christiane, it’s always good to be with you.

AMANPOUR: So, what did you think of the optimistic note and the rather urgent note that, you know, a top CEO, Paul Polman, has just sounded? Does

it make sense what he’s saying?

MCKIBBEN: Well, Paul deserves great credit. If there’s anyone who has tried to move a big company in the right direction, it’s him. Sadly, he’s –

– well, he’s very much in the vanguard and there haven’t been as many followers yet as one would hope. That’s particularly true in the two most

important sectors, the fossil fuel industry itself and the financial industry that supports it. And that’s, I think, where most of the activism

now is being aimed.

AMANPOUR: So, what would you suggest? Because, I mean, let’s just talk about activism. One of the quotes from your recent newsletter, you know, a

study by researchers at Yale and George Mason Universities found that one in five Americans said they wouldp “personally” engage in non-violent civil

disobedience against corporate or government activities that make global warming worse if a person they liked asked them to. That’s the whole peer

pressure that leads to change, the peer imperative.

What would you say to these other corporations, then, that we’ve sort of listed who are beginning to say things?

MCKIBBEN: Well, look, that pressure is building because movements are building. You know, there’s Greta Thunberg and 10,000 other young people

like her out pushing hard. It’s building because people look on TV and see Australia consumed in inferno, and those people are increasingly getting a

chance to take a stand.

The next big day is going to be April 23rd in this country, when we think that many thousands of people will be committing civil disobedience in the

lobbies of Chase Bank branches around the country. Why? Because JPMorgan Chase, the biggest bank in the world, is by far the biggest funder of the

fossil fuel industry. Since all those good words in Paris, they’ve put $196 billion in loans into the fossil fuel industry.

You know, it’s true that President Trump pulled us out of the Paris Accords, but people like Chase Bank were undermining us before we could

ever even get going. So, we have to break this kind of web of influence.

Look, the lead director at Chase Bank, the guy who runs their board of directors, before he took that job was the CEO of Exxon, the biggest, at

the time, oil company on earth. So, there’s an enormous amount of power and it only — citizen power can begin to break it up. But that citizen power

can really work.

You know, we’ve talked in the past about this divestment movement that we launched seven or eight years ago to get institutions to break their ties

from fossil fuels. At the start it was small. But at this point, we’re at about $12 trillion in endowments and portfolios that are divesting from

coal and gas and oil.

AMANPOUR: So —

MCKIBBEN: And that’s putting enormous pressure on the sector. You know, Shell oil said in their annual report last year that divestment had become

a material risk to its business —

AMANPOUR: What I was going to ask —

MCKIBBEN: — which is good because Shell oil has become a material risk to earth.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Well, I was going to ask you, is divestment then — because a lot of people talk about it and it gets not very much coverage. Is

divestment a bigger game-changer than activism on the streets, votes at the ballot box or even corporations — I mean, I know you say they’re not

enough yet, corporations, which, you know, as we said to Paul Polman, as he, you know, admits, you know, these are the biggest emitters of, you

know, carbon product into the air. So, is divestment bigger or these other things?

MCKIBBEN: Well, so divestment has become a huge tool. As Paul said, it was outside pressure that begins to get corporations to move. And the most

important corporations to move are the handful, that as you pointed out, supply 75 percent or 80 percent of emissions. So, that’s where the pressure

is coming.

I look at it, Christiane, as if there’s two levers to pull here. One is the political lever. In the U.S., 2020 is a big year. Today is a big day. You

know, so there’s lots of people working hard to change our political system. But we also have to pull this financial lever. Because Washington

doesn’t really rule the world anymore, but Wall Street kind of does. And if you could begin to get the big banks and asset managers to change how they

value and how they deal with the fossil fuel industry, you would be a long way there.

And it’s starting. This campaign is only about six months old. People can go to stopthemoneypipeline,com to learn more about it. But if it’s first

six months, it’s persuaded some of the biggest insurance companies, some of the biggest banks, to begin at least to change their policies.

The biggest success came six weeks ago when one of our chief targets, BlackRock —

AMANPOUR: Yes.

MCKIBBEN: — the biggest asset manager on earth, their CEO put out a fairly remarkable letter saying that everything in finance is going to have

to change because of climate change. Now, we don’t know whether he means it yet. We’re going to have to, you know, monitor hard to see if they’re

actually taking steps to match their rhetoric. But man, it’s a good example of what happens.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And we’re following this, because —

MCKIBBEN: And people begin to push hard.

AMANPOUR: — we actually interviewed their sustainability chief there, Brian Deese. And you’re right, Larry Fink —

MCKIBBEN: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — said that one of the biggest impacts on finance is climate change and they’re going to have to change the way they do things. So,

you’re right, it is moving slowly.

I do just want to ask you about, you know, what will it take to get the governments to change? Because as we’ve pointed out and as we talked with

Paul Polman, still the biggest emitters, China and the United States, are by no means doing what they need to do on combatting the emissions. Do you

think corporations can move governments?

MCKIBBEN: I think people can move governments if they push hard. And one of the things they have to do is push hard on corporations. But governments

act, at best, slowly, even when you get them in motion. And that’s one of the reasons that we’re also working so hard on this financial angle.

Because if you think about it, you know, if tomorrow JPMorgan Chase said, we’re not lending any more to the fossil fuel industry, that would, A, be

felt instantly. Every stock market in the world would react within minutes. And B, it would be felt globally.

Our money system remains dramatically interconnected in the way our political systems are increasingly disconnected. So, I think we have to do

both and we’re working hard on both. But there is a lot of excitement right now around these financial institutions.

One reason is you’ve seen that — say in the United States, that map that Donald Trump always holds up that shows all the red parts of America and

they’re all for him and on and on and on, just these little slivers of blue where people are voting against him. Well, look, you hold up a money map of

the United States, it’s just the opposite. Most of the money is concentrated in those little slivers of blue. So, that’s the electorate, as

it were, that BlackRock and JPMorgan Chase and the others have to worry about.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, I just need to ask you, because you keep mentioning JPMorgan Chase presumably for a reason. But didn’t you just tweet about

them just very recently about the fact that they said that they, you know, would no longer invest in arctic fossil fuels?

MCKIBBEN: Yes. They made a small concession last week in the face of this pressure. They’re beginning to take stock of what they’re going to have to

do. But people continue to push them very, very hard. I was arrested in the lobby of the JP Chase branch nearest the U.S. capital last month at the

launch of this campaign, and we think that there will be people in the lobbies of thousands of their branches on April 23rd. That’s the day after

the 50th anniversary of Earth Day.

So, we’re all going to commemorate what we’ve done over the last half century, but then we’re going to go right to work trying to make sure that

the next half century goes faster. Because it’s got to go faster. That’s the thing. The problem here is not that we’re not going to get where we

need to go eventually. Look, sun and wind are now the cheapest way, as Paul pointed out, to generate power around the world. So, eventually, we’ll get

there. But we don’t have eventually.

The IPCC, the scientists have told us that if we haven’t made dramatic transformation inside of 10 years, then our chance of meeting the Paris

targets is essentially nil. That’s why, though it’s sort of crazy, people are going to jail. It’s why they’re cutting up their credit cards. It’s why

they’re taking really dramatic action to hold to account the people who are the kind of glue of this fossil fuel system.

AMANPOUR: Bill, I want to put up a map that we have. You must have seen it. Everybody has seen it and everybody is talking about it, really. One of

the — you know, if there can be a side benefit to coronavirus, it is that it’s helped a little bit with the pollution of the skies, certainly in

China at least, where the virus has dramatically reduced the amount of industrial activity there. And you can see the before and after map.

I mean, surely even to the most vociferous doubters, the people who talk about hoaxes and that climate change is just, you know, a nonsense

constructed by the media and other nefarious actors, surely that map is once and for all proof. What do you say to that?

MCKIBBEN: Well, I don’t know. The president of the United States has now decided that the coronavirus is a hoax too. You know, everything is a hoax.

But yes, look, there’s nothing good in any way about the coronavirus, obviously. And the fact that it’s cutting carbon pollution momentarily in

China isn’t the right way to go about it, because it will rebound instantly.

AMANPOUR: No, I know it’s not the way. I know it’s not the way, Bill. But I’m just struck by the visible proof.

MCKIBBEN: I understand. I know you’re not saying that, but, yes, you’re absolutely right, absolutely.

I mean, look, there’s no doubt what’s going on anymore. Only people who have some vested interest in this system are still trying to maintain the

idea that there’s some doubt here.

I mean, anybody — all anyone needs to do is look at those unbelievable pictures from Australia earlier this year. I mean, we had thousands of

people in one of the richest countries on Earth standing on beaches wading into the ocean because it was the only way to escape the firestorm that was

engulfing their communities.

That’s what’s coming to the world. That’s what much of the world looks like already. So, we have only increased the temperature one degree. We talk

about 1.5 or 2 degrees as if they’re kind of goals. Really, they’re horror shows. They’re just not as bad as the path that we’re currently on.

That’s why immediate, quick and dramatic action is so important. If there are people out there who’ve been keeping their powder dry, now’s the

moment. We need you. We have leverage for the next few years to make huge changes.

But, after that, our ability to influence the outcome of this story really begins to ebb.

AMANPOUR: So, even as the Trump administration rolls back a huge number of regulations, EPA laws governing water and air and the rest, and even as

some of its officials try to insert distorting language that not just denies climate change, but totally distorts the science, like how carbon

dioxide is somehow actually good for us, even as that is happening, there is a lot of good news, as we heard from Paul, as we have heard from you, as

we have heard from many mayors, on a subnational level, so to speak, state level and mayoral level.

Things are happening in a very big way. So I want to ask you about some of the solutions and some of the good news, because I think people need to

know that there are solutions that they can work for.

You have a scoreboard, a scorecard, that we’re going to put up briefly right now that you list about some of the things that have actually

transpired that work.

OK, walk me through some of your latest — we don’t actually have the graphic, but tell me, on your scoreboard, some of the things that work,

Bill.

MCKIBBEN: Well, there’s all sorts of things that are starting to happen all over.

I mean, you can just list morning to night. I just got a great e-mail from friends of mine saying, you have got to look at this tour that indigenous

people have put together of tiny houses, and they’re building small, sensible houses. And they’re increasingly building them in the path of the

kind of pipelines that people are trying to block.

There’s incredible action to stop the biggest fossil fuel projects on Earth. Last week, they pulled the plug on what would have been the biggest

tar sands mine on the planet, largely because of incredible indigenous opposition in Canada.

They just blocked plans for a huge gas pipeline across the East Coast of the United States. Why? Because the people who wanted to do it said the

investment climate has changed. That is to say, all those people who worked so hard on divestment and got done what needed doing, they have got the

message beginning to sink in that this is not where we’re going anymore.

So all this kind of work in movements, we fight each fight on its own, right? You have to block this pipeline, divest that college, on and on. But

the basic bottom line is, what we’re fighting for is to change the zeitgeist, people’s sense of what’s normal and natural and obvious.

And that what’s happening now.

AMANPOUR: And, to that point, we do have this image. And that is the cover of the latest “National Geographic,” which talks about the end of waste, of

trash.

And I wonder whether you can talk a little bit about, of course, trash and the amount of natural resources, including food and clothes, not to

mention, obviously, carbon, we just toss away.

And people are talking about a circular economy now, instead of a buy-and- dispose economy.

MCKIBBEN: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Talk to me a little bit about that.

MCKIBBEN: Christiane, that change can’t come fast enough.

There’s a remarkable article that came out a few hours ago from “Rolling Stone,” and what it — look at is plastic pollution around the world. You

kind of know about this and been listening to people talk about straws and things, but the numbers are unbelievable.

They say there’s so much micro-plastic in circulation now, so much little tiny pieces, that every person on Earth is consuming the equivalent of

eating a credit card every week, you know?

That plastic is largely now the result of big oil deciding that it needs a new outlet for its product. As people begin to drive Teslas, and don’t need

gasoline anymore, they’re left with all this oil.

And one of the things they’re doing is putting up plastic factories around the world. So, beginning to cut those chains is really important. Last

night, at midnight, or the night before, New York state passed — it went into effect the new law saying no more plastic bags in New York state.

And, of course, they’re following people around the world, from Bangladesh on down the list. Those are good signs, but they’re not yet adding up to

enough. That’s why we need to keep pushing and pushing hard. That’s why we need people in the streets.

And I tell you, the best news of all is that young people are making those connections. They’re understanding that their economic future lies very

much in precisely the kind of circular economy you’re describing.

I can’t tell you — I mean, I — just here at Middlebury College, where I am, just how excited young people are to get to go to work in those

industries in that new world, and how completely unexcited they are about going to work for the guys who’ve been screwing things up.

I don’t know if you have been paying attention, but there’s a remarkable story the last few weeks. Paul, Weiss, the law firm that represents Exxon,

each time it has a recruitment meeting — as Paul was sort of mentioning this — each time they have a recruitment meeting at Harvard, at Yale, at

NYU, law students are saying, standing up with banners and saying, we’re not going to go to work for you, because we do not want to take our brains

and use them to help carry out the destruction of the planet. That’s not what we’re here for.

So, with young people, it’s really exciting to see that kind of energy in play now.

AMANPOUR: And — it’s this is the election that could actually make that kind of energy a reality when it comes to government in the future.

Bill McKibben, thank you so much, indeed, for joining us from Vermont.

And now: “The United States of America is segregated, and so is pollution” — those words from our next guest, the so-called father of environmental

justice, Robert Bullard.

As a sociologist in the 1970s, he shone a light on how minority communities in Houston, Texas, suffered most from pollution. Since then, he’s written

more than a dozen books on sustainable development, environmental racism, and climate justice.

And he’s been talking to our Walter Isaacson in Texas about all of this.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: I have been absolutely fascinated by the concept of environmental justice.

Tell me what that concept means and how you became the father of that.

ROBERT BULLARD, AUTHOR AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCHOLAR: Well, environmental justice embraces the principle that all communities are entitled to equal

protection of our housing, transportation, employment, and transportation energy.

And so it’s a concept that’s rolled in equal protection, equal access, equal enforcement. And it’s not a fuzzy issue. It’s an issue of the right

to live in a neighborhood that’s not overpolluted, a neighborhood where your kids can play outside on the playground that’s not next to a refinery

or a chemical plant.

ISAACSON: And that’s how you got into it. It was 1978.

BULLARD: 1978. That was so long ago. And it was an accident. It was an accident.

You know, my wife came home one day and said, Bob, I have just sued the state of Texas, and I have sued this company that’s trying to put this

landfill in the middle of this suburban middle-class black community in Houston. And she said, I need somebody to collect data for this lawsuit and

put the — where the pins are and where the landfills are on a map.

And I said, well, you need a sociologist. She said, that’s what you are, right?

(LAUGHTER)

BULLARD: That’s how I got roped into this. I got drafted.

ISAACSON: And you discovered that there were like seven landfills. How many of those seven were in African-American neighborhoods?

BULLARD: Well, what I discovered, from the ’30s up until 1978, that five out of five of the city-owned landfills were in black neighborhoods. Six

out of the eight of the city-owned incinerators were in black neighborhoods, and three out of four of the privately owned landfills were

in black neighborhoods, even though blacks only made up 25 percent of the population during that period of time.

And this is in a city that — it’s the fourth largest city and a city that doesn’t have zoning. So somebody was making these decisions. And what we

found is that it was not random. Everybody produces garbage, but everybody doesn’t have to live next to the landfill.

And it was not just a poverty thing. The subject of the lawsuit, Bean vs. Southwestern Waste Management, was a middle-class black neighborhood of

homeowners; 85 percent of the people owned their homes.

And so it was not a poverty park. It was not a ghetto. This was a solid middle-class neighborhood of houses and people and trees.

ISAACSON: The City Council of Houston that’s making that decision back then, what’s the racial makeup of that city council?

BULLARD: All white.

ISAACSON: All seven?

BULLARD: All seven.

ISAACSON: Yes.

BULLARD: So you get this whole idea of environmental justice also means having access to decisions that are being made and making sure that there’s

access, and that no one segment of our city or a county or region should be making decisions for other people.

And so the idea that this was a policy of not having individuals on the City Council in that room saying, well, let’s not just put all the

landfills or the incinerators or the garbage dump in this one area.

And so it’s a matter of equity, a matter of fairness and a matter of civil rights.

ISAACSON: And how does climate change affect this?

BULLARD: Well, climate change — if you look at environmental justice, climate change basically overlays this whole issue of who has contributed

most and who is going to be impacted the greatest.

And if you look at the footprint of climate change — and climate change is more than parts per million and greenhouse gases. It also includes who is

most vulnerable. Who is going to have the burden of living in these areas that are going to be hit hard, whether it’s droughts or there’s flooding or

whether other kinds of issues.

And, again, climate change, sea level rise will exacerbate the inequities that already exist. If people are poor, they’re in low-lying areas that’s

prone to flooding, you’re going to get more flooding. You’re going to get more droughts and more disasters. You’re going to get more of issues of the

widening gap between haves and have-nots.

And you’re going to get this whole piling on effect of not having, you know, a level of resilience to bounce back because of a flood.

ISAACSON: So let’s be specific. You were here for Harvey, right? How many inches of rain did Harvey dump on Houston?

BULLARD: Fifty-two, 53, whatever. Nobody counted on that.

I have worked on environmental justice and climate issues and disasters for 40 years, and working with other communities that have been forced to

evacuate. I never had to be evacuated until Harvey.

In this case, it was very unique for me and very unique for a lot of people, because, in some places, some neighborhoods, some areas had never

flooded before.

ISAACSON: How did the city flood, white areas vs. black areas?

BULLARD: Well, if you look at the GIS maps, studies just came out last year showing that the communities that historically that have flooded over

a period of time — we’re not talking major storms. We’re talking mostly African-American, Latino areas in terms of the East Side.

Divide the city in half. Harvey basically followed that pattern. Even though a large part of the city flooded, the areas that got hit the hardest

are the areas that historically have always gotten hit hard.

ISAACSON: Houston is famous for not having many zoning laws. How does that affect things?

BULLARD: Well, as a matter of fact, Houston is a no-zoning city, and it’s very proud of that. It’s unrestrained capitalism. And it means that,

historically, it’s the only residential protection land use device is with deed — renewable deed restrictions.

But the fact is that we have a lot of our land uses that’s willy-nilly, a lot of building that’s in areas that we probably shouldn’t be building in.

And the idea of, how do we make corrective action that’s happened over the last 50, 75 years, it’s hard to do that now.

So that means that we have to come up with sensible planning. We have to talk about how we’re going to, in some cases, probably restrict the kinds

of development that most cases would be dictated by money, as opposed to some common sense. And so–

ISAACSON: Wait. Give me an example of that.

BULLARD: Well, in terms of a lot of the houses that flooded on the western part of the city were built right up to the reservoirs.

And — Addicks, Barker reservoirs. And these — and those houses, we’re not talking low-income, middle-income. We’re talking very well-heeled families,

million-dollar, $2 million homes that were built in a floodplain and that were built in the areas that, with an event like Harvey, is bound to flood.

And you talk about what it means to provide protection, not just for well- heeled communities, and the idea that, if we can provide the kinds of flood protection and flood mitigation and the kinds of restructuring of our land

uses, and allow for some communities to somehow relocate, it has to be a plan that brings a lot of communities to the table.

And, historically, Houston has not been a city that has been diverse when it comes to decision-making. It’s been mostly a top-down. And so I think

Harvey has brought a lot of rethinking of what that means.

ISAACSON: Has Harvey brought people of different socioeconomic and racial groups together?

BULLARD: Oh, yes. Oh, yes.

But you have to look at it and say, it took a biblical flood to bring a lot of the groups and organizations that generally had not worked together on a

lot of issues, organizations that work on wetlands and on prairie issues, issues of environment, pollution, industry, transportation.

It brought a lot of groups together. We came — almost three dozen groups came together and decided that we need to be talking, we need to be working

together. And we came up with this organization named the Coalition for Environment, Equity and Resilience, CEER.

And, again, the heart of that whole thinking is an equity lens. And one of the first things we did is, we came together and came up with this

framework. And we presented the framework, equity framework, to the county, Harris County. And they basically adopted this whole idea that future

development and future funding of projects dealing with Harvey or flood mitigation or going forward must be looked at through an equity lens.

ISAACSON: Houston, how segregated is it racially and economically?

BULLARD: Well, you know, Houston is still segregated.

It’s segregated by race, and it’s also segregated by income. And, again, if you look at this whole idea of concentration of white affluent census

tracks, or zip codes, you can see that increasing.

You can also see the increasing numbers of low-income families, families of color, concentrated in those census tracks, in those areas.

ISAACSON: Wait. Wait. So you’re saying it’s becoming more segregated?

BULLARD: More income-segregated.

ISAACSON: Why?

BULLARD: Well, that’s a big question of the day. And it’s not just a Houston question.

We are becoming more and more separate and apart by income. And affluent people feel more comfortable living with affluent people. And, oftentimes,

poor people don’t have a choice but live around poor people.

And housing choices oftentimes will dictate where people live. And the fact is that Houston and most major cities in this country have a housing

affordability issue. And if you have to drive to qualify, which means drive long distances to qualify for housing in terms of ownership, that means

that the housing that’s available, people have to settle for less.

And more and more people are settling in those areas where they can afford. That means that you’re having more and more concentrated areas with people

of color, as well as poor people. Now, that’s not the best way to create healthy, livable, sustainable, resilient cities, but that’s what we get

when we let market forces drive it, as opposed to trying to assist and support a sane program of creating more, what — what do they call it,

mixed income housing and mixed use.

ISAACSON: Right.

BULLARD: I will tell you another thing.

It’s not just the housing being segregated. So is pollution. Pollution is segregated, which means that, as you start getting more and more low-income

families and families of color concentrated in areas where there’s lots of pollution, more and more pollution gets put in those areas.

And so you get the segregation of income and race, but you also get the income of pollution. And that’s where we say — you know, I wrote a book on

this called “The Wrong Complexion for Protection.”

And it means that — and I’m not just talking about race. It’s also income. Middle-income African-Americans are more likely to live in neighborhoods —

when I say middle income, I’m talking $50,000 to $60,000 — are more likely to live in neighborhoods that are more polluted than whites who make

$10,000.

You say, how can that be? It means that there is a racial and economic dynamic in housing that allow low-income whites to move into middle-income

areas and to exit polluted neighborhoods, whereas institutional racism will keep black families, middle-income, in those neighborhoods.

ISAACSON: After Katrina, we all realized in New Orleans we were in the same boat, and it did bring us together some. And we did rebuild the Lower

Ninth Ward, but there was more of an integration of the city.

Do you think environmental catastrophes like Harvey will start doing that in places like Houston, make people realize we’re all in the same boat?

BULLARD: Well, you know, I hope we don’t have to wait for a disaster.

But it did. And the kinds of — in some cases, these wakeup calls oftentimes are the only thing that will wake us up, and to a reality that –

– I have a saying, that when we don’t protect the least in our society, we place everybody at risk.

We don’t strengthen the levees or we don’t provide flood protection for one segment, we place everybody at risk. When we don’t provide protection in

terms of immunization or whatever, then it will place everybody at risk.

And so it seems to me that a justice frame, an equity frame should be the logical framework to accept. But, you know, we are a hard-headed society.

(LAUGHTER)

BULLARD: It’s almost like we need a two-by-four to hit us over the head and wake us up and say, aha.

And we need those aha moments before disasters hit. But I do think that Houston post-Harvey is a different Houston in terms of thinking, in terms

of mind-sets, in terms of thinking about this whole idea that we are a big city, and that we can’t just somehow have communities that are invisible.

I wrote a book in 1987 called “Invisible Houston.” Houston in 1987 had the largest African-American population of any city in the South. There were

over a half-million black people in Houston, more people than in Atlanta or New Orleans.

And so the idea that, even though you had this large black population, the black community was invisible when it came to landfills, incinerators, was

invisible when it came to economic development, providing the kinds of growth and planning that will build communities that was — that had those

things.

Middle-income African-American communities in Houston didn’t have the same kind of amenities as the low-income white communities. So the idea that

invisible, that invisibility must be erased, and we must make all communities visible, so that they can join in this new green energy economy

and post-disaster to talk about building resilience.

There has — you know, when we talk about climate, we talk about climate justice. When we talk about the environment, we talk about environmental

justice. When we talk about energy, we talk about energy justice.

All these things, when you look at the justice framework, it can apply to almost all the aspects when we talk about issues around sustainability.

ISAACSON: In Houston, and to some extent in all of Texas, the energy industry just doesn’t even like to utter the words climate change.

Is it possible to move towards environmental justice without confronting climate change head on?

BULLARD: No, it’s impossible.

When we talk about climate change and we talk about environmental justice, when we start connecting, you know, the tissue of climate responsibility

and the issue around vulnerability, you can’t get around solutions, real solutions, without talking about justice inequity.

That’s why the climate justice frame is a frame that, as I said, is more than just looking at greenhouse gases in parts per million. It brings in

the issue of which communities are vulnerable, which communities have contributed least to the crisis, but are feeling the pain right now, first,

worst, and longest.

That’s true here in Houston. It’s also true in Texas. It’s also true in the United States and globally, this whole issue of vulnerability and the whole

issue of, how can we make sure that our plans do not further marginalize already vulnerable populations by creating plans that somehow exacerbate

that vulnerability and create more problems for that — quote — “invisible group,” the group that may not necessarily be in the room when they’re

deciding what to build and where to spend moneys.

That’s the justice part. And even though the state of Texas may not recognize climate change as a concept, the whole issue of vulnerability and

the whole issue of severe weather events, you look at the map, and there’s no way for the state not to look at where the hot spots are and where the

solutions need to be, where the mitigation and the adaptation will have to occur, no matter whether they believe in it or not.

And that’s why I tell people, I said, believing in climate change is not — it’s not the issue. It’s like asking somebody, do you believe in gravity?

And it’s not — believing in gravity is not — is not an issue.

If you climb up a 50-story building and jump out, gravity will kick in. And so whether you believe it or not, it’s real.

ISAACSON: Dr. Bullard, thank you so very much.

(CROSSTALK)

BULLARD: My pleasure. My pleasure. Thank you.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And do you believe in gravity?

And, finally, word today that Wells Fargo is joining a growing list of global banks that no longer fund new oil and gas drilling in the Arctic.

And, as we discussed earlier, that is legitimately a big deal. Since 1987, when President Ronald Reagan first recommended that Congress allow

drilling, the issue has been a political mine field, with Democrats working to block new exploration, as Republicans chanted “Drill, baby drill” at

their 2008 National Convention.

Now, along with Wells Fargo, J.P. Morgan and more, major corporations are heeding the protests of environmentalists and Native Americans and making

real progress at last.

That is it for our program tonight. Remember, you can follow me an the show on Twitter. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS. Join us again tomorrow night.