Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

What in the world is going on behind the coronavirus curtain? Many leaders are using this crisis to grab special powers and violate civil rights.

Veteran diplomat, William Burns, joins us.

And relationships under lockdown. The good, the bad and the ugly with therapist, Orna Guralnik, and sociologist, Erik Klinenberg.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

STUART STEVENS, AUTHOR, “IT WAS ALL A LIE”: Why the Republican Party is failed tremendously on this —

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: As the pandemic surges, a leading GOP political consultant takes the blame for his party’s rejection of science and good government.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour from London, still working from home where today, we take a look at the many ways

coronavirus exacerbates global problems, both large and small.

In China, where the outbreak began, the government says new cases dropped practically to zero. But the World Health Organization warns that

coronavirus epidemics are “far from over” in Asia and in hard-hit Europe. While the death toll is still rising in Italy and Spain, reports of new

cases in Italy are declining.

The United States now has the most confirmed cases in the world at more than 170,000, with New York still the nation’s main hot spot. And last

night, Governor Andrew Cuomo described the affect it is having on health care workers there. This is what he said.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

GOV. ANDREW CUOMO (D-NY): The staff is getting exhausted. I had one nurse say to me more than physically exhausted, I’m emotionally exhausted. You

know, this is weeks and this will go on for weeks.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And, of course, the governor is calling for medics to come from all over the states to help New York. And the World Bank reports that the

pandemic could push millions of people into poverty.

And in a startling headline “The Washington Post” says coronavirus has killed its first democracy. As Hungary’s government use this is crisis to

move towards authoritarian rule. And Israel and even the U.K. grab emergency powers without an end in sight.

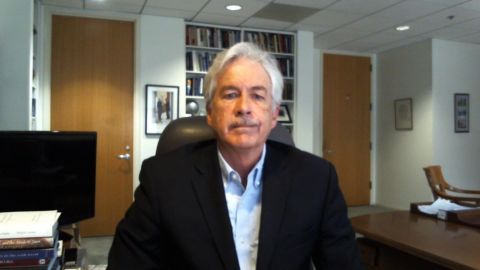

William Burns is a distinguished veteran of America’s Foreign Service and he’s been a senior state department official. And he says this difficult

moment could yet turn out to be an opportunity to restore Democratic leadership.

William Burns, welcome to the program.

So, you have written this week, I guess, looking around at what’s happening in the world under cover of the coronavirus at a whole load of things that

are going on that ordinarily, you know, one would be paying very, very strict attention to. What grabs you the most? How do you put this moment

into historic context?

WILLIAM BURNS, FORMER U.S. DEPUTY SECRETARY OF STATE: Christiane, first, it is good to be with you again.

I think this is one of those moments that comes along rarely, maybe two or three times a century on the international landscape. We have a crisis, in

this case, an awful pandemic, intersecting with a set of transformations that were already under way.

You go back, you know, a century ago, to the end of the First World War, the rise of new global powers, great power competition, huge changes in the

global economy, and what happened was the terrible influenza pandemic at that time turned into an accelerant, it accelerated the fragmentation. And

I think we face, you know, many of the same risks and threats today.

But, you know, if crises like this are accelerants, they can also help clarify choices as well. And, you know, if we look at that landscape

honestly, if the United States, in particular, understands it and understands our enduring strength is honest about the missteps we have made

before, you know, this can help also clarify some of our choices looking out over the next five or 10 years.

AMANPOUR: So, let me just ask you because you just mentioned 1919 and, you know, after the First World War and you wrote that, you know, Woodrow

Wilson there trying to deal with the post-war realities just as, I guess, the tail end or maybe the full brunt of the influenza epidemic was hitting.

And you have said that it could be, you know, the whole of civilization in the balance, at least that’s what Woodrow Wilson’s doctor said at that

time. Do you think that’s the case right now?

BURNS: Well, I think, you know, you look around the world, it is a really complicated and competitive landscape with the rise of competition, you

know, between the United States and China, in particular. Huge transformations, not just politically and economically but also

environmentally and technologically around the world. So, there’s a huge amount of uncertainty and risk today, as well.

And I think, you know, the — you see the distinct possibility of future waves of the coronavirus pandemic sweeping over parts of the world,

especially in the developing world which are already very vulnerable. And, you know, where the human toll could be much greater than we have seen

already in more developed countries. So, it’s a moment of real consequence.

AMANPOUR: Indeed. And we have said that the World Bank is very concerned that this crisis could push millions and millions of people into poverty,

whether it’s from India or further south and in Africa and many, many other places. And we are going do get to that in a moment.

But I want to ask you because you said great power. Rivalry is back. You have said that sort of a center of gravity is shifting from west to east.

And we saw that “The Washington Post” talked about coronavirus claiming, killing its first democracy. As Hungary, which already calls itself quite

proudly, describes itself as an illiberal democracy has now basically demanded and got total overwhelming parliamentary support for extraordinary

powers and for the prime minister, Orban, to rule by decree.

How do you assess that and do you think, you know, that this is kind of for this moment only or is this a troubling trend even after the coronavirus

crisis?

BURNS: No, I think it’s a real gathering danger. I mean, just like a virus can worsen, accelerate, aggravate preexisting health conditions, I think

this virus crisis, this pandemic can accelerate, worsen, aggravate preexisting political conditions.

So, in Victor Orban’s Hungary, you know, he had already bludgeoned tax and balances, the legislature, the judiciary, you know, he had already battered

civil society as well as the free press. And this is proven to be an opportunity for him now to take on fairly sweeping emergency powers to be

able to rule by decree.

And, you know, this is an old playbook for authoritarian leaders. We saw it in the period between the First and Second World Wars in Europe. But you

add on to that old playbook new tools, you know, new surveillance technologies, which, you know, for many authoritarian leaderships around

the world provide an opportunity to further tighten the grip. So, it gets really worrisome.

AMANPOUR: I mean, it is extraordinary, the range of places, you know, with varying degrees that this kind of grabbing, consolidating of power, rule by

decree, emergency measures have sprung up all over the place.

You know, they say, well, yes, of course, we have to do this because we have to — we can’t wait to take measures regarding coronavirus. But

whether it’s Brazil, whether it’s Thailand, whether it’s, as we just said, in Europe, here in the U.K., many, many places are doing this right now.

BURNS: No, it is true. And in some places, you can see the logic of it and dealing with a crisis but, you know, in other places and Victor Orban’s

Hungary, I think, is a classic illustration of this, you’re seeing authoritarian leaders use this to tighten the grip and beat back democratic

governance.

AMANPOUR: Now, one of the places, obviously, maybe places you’ve worked on throughout your long career. But Iran was a major one for you, you were

part of the original back channel negotiations before the nuclear deal. And what we have seen there, in this instance, is that Iran has the most

coronavirus cases in that region. It’s got — it says it’s got 50,000, but people believe the real number is much, much higher.

Just talk to me about, you know, first of all, that government which is an authoritarian government and controls the news, controls, you know, what it

likes to put out. What are the dangers of those kinds of governments saying whatever they say but trying to tackle a very real problem at the same

time?

BURNS: Well, the dangers are, first and foremost, I think, for the people of Iran and more broadly for the people of the region if these spreads. But

for the people of Iran, you know, they’re caught between the ruthless and oftentimes cynical miss management of this crisis by their own government

and economic strangulation that comes from sanctions led by the United States.

And so, you know, it is a really difficult position for people there and there’s an urgent humanitarian need, I think, to look for ways in which we

can help meet that need, not just, you know, from Europe but also from the United States as well. But at the core of this, I think in a lot of ways

is, as I said before, the ruthless and cruel mismanagement of this crisis by the Iranian government itself.

AMANPOUR: And you know, they claim a certain number of deaths but opposition parties claim that it’s much, much higher. They believe the

deaths could be as many as 12,500 in about 300 cities around the country. We probably will never really know what that is in any time soon.

But you talk about international policy. What should be the humane and legal international policy no matter whether you like the government or the

people or not when there’s crisis like this? For instance, Iran for the first time since 1962 has called on the IMF for a $5 billion loan.

Apparently, the United States has the power to say yes or no and hasn’t ruled on that and even humanitarian supplies are being blocked from going

from certain Central European countries by truck to Iran. Is that part of the sanction’s regime?

BURNS: No. I mean, I think there’s an urgent humanitarian need and I think despite the, you know, deep differences between the United States and Iran

we ought to look for ways in which we can make clear to other governments, to foreign companies that they can provide the sorely needed humanitarian

supplies, medical equipment that the people of Iran need right now.

The challenge is that, you know, the sanctions regime, as it exists now, theoretically doesn’t prohibit the provision of those kind of humanitarian

supplies. But in practice, you know, those — that kind of transfer is inhibited financially because foreign companies, other governments are

worried about the — you know, the power of the U.S. financial system being used against them. So, I think there’s more that the United States could

do. You know, recognizing the deep political differences between the United States and Iran that we could do to help at least ensure the provision of

some of that desperately needed humanitarian assistance.

AMANPOUR: The Trump administration says that — as you point out that, you know, they would provide help but, of course, on the ground, as you say, it

is actually not happening and it is being impeded by the U.S. But this brings up a new or rather another question, and that is, in these kinds of

situations should the United States be taking advantage and looking at what they might think are weaknesses whether it’s in Iran, whether it’s in North

Korea? Because Secretary of State Pompeo has said, now is the time to keep up the pressure both on Iran and on North Korea. Is this the time to do

that?

BURNS: Well, I think the problem with that theory, you know, intensifying the maximum pressure campaign is that, you know, if it is aimed presumably

at bringing about either the capitulation of the Iranian regime or its implosion, and I think what you are more likely to see, sadly, is the

implosion of large parts of Iranian society, mute suffering on the parts, you know, Iranian citizens. And the regime itself just tightening its grip,

the supreme leader, the Revolutionary Guards around him tightening their grip on authority.

So, it seems to me this is one of those cases, you know, where providing humanitarian assistance or at least allowing it to be transported, I mean,

is not only the morally right thing to do, but it is also the diplomatically smart thing to do, in the sense that the Iranian regime, for

example, you know, is animated in a sense by the notion that the United States is implacably hostile to the Iranian people. This is a way of

undercutting that argument.

Maybe it could create a circumstance if the U.S. were to take a more flexible approach in which we could help secure some important but modest

steps like the release of, you know, Americans unjustly detained in Iran, maybe we could use this to help ease, you know, the — use the overall

pandemic crisis to help ease tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran or to begin to open up the door to a diplomatic resolution of the horrific

conflict in Yemen today.

So, there’s a lot of ways in which, I think, you could at least try to explore the possibilities that might be created even by the most horrific

crisis.

AMANPOUR: So, that raises an interesting point because, you know, as you can see from the T.V.s, from the news, there’s only one story. And for the

last, I don’t know, several weeks, it’s only been this story around the world.

Do you think, though, that governments, foreign policy institutions, the State Department, et cetera, should actually be conducting diplomacy and

the kind of things that you are saying right now or is everybody just, you know, completely maxed out by trying to deal with this? I mean, for

instance, North Korea is busy doing tests, rocket and missile tests, and you wouldn’t know it because there’s no reaction to it.

BURNS: You know, it’s really hard. I mean, I have served through circumstances like this in government before and, you know, you’re

consuming preoccupation is dealing with the crisis of the moment.

But, you know, that’s what governments exist for in public servants exist for is to try to think ahead a little bit, to see opportunities even in the

worst crises, even as you’re wrestling with all the immediate challenges that flow from those crises, but also, to look ahead. And, you know, as you

mentioned earlier, Christiane, I think there’s a huge wave to break over the developing world, you know, in the not too distant future, very

vulnerable societies.

The United Nations earlier this week broadcast an appeal for emergency assistance, but that’s just a small down payment, I think, on what’s going

to be required. And so, that’s also one of the challenges for governments right now as difficult as it is for developed countries, whether it’s in

the United States or in Europe or in China to deal with this kind of a challenge. You know, we really need to look ahead at the next waves that

are going to break as well.

AMANPOUR: So, you know, then what should the U.S. be doing as leader of the world, the most powerful country, even though this pandemic is hitting

it very hard right now? What should the U.S. be doing, if anything, to stave off the worst of what might happen in the poorer parts of the world?

Because as we have seen, you know, social isolation may be OK for people who have got dwellings big enough to socially isolate in different parts

and stay at home.

But look at what’s happening South Africa in the townships, you know, huge numbers of very, very dense families, 10, 11 people maybe in one room.

They’re locked in. They can’t — you know, it is just so difficult. They’ve lost their jobs. They can’t go out. What should happen for these countries

who don’t have, you know, a treasury department or a chancellor who can bail the country out to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars,

pounds, yen, whatever it might be?

BURNS: Well, it really is just as you described the kind of perfect storm of, you know, societies which are already fragile, densely packed, you

know, families that are living day-to-day, they can’t afford the physical distancing that we are trying to practice in the U.K. over the United

States right now, nor can their governments afford to provide financial support to families, you know, in order for them to stay at home. Their

health care systems are also for all the challenges that we’re finding in the United States right now, they’re far more vulnerable as well.

So, while there are limits to our power, there are limits to our capacity in the United States, you know, this is a time for disciplined American

leadership, the kind of leadership that we saw during, you know, previous global health crises, whether it was HIV/aids in the George W. Bush

administration or Ebola in President Obama’s administration, this is a time for United States to demonstrate leadership, to work with international

institutions, to work with rather than against China on the issues to the maximum extent possible, to begin to, you know, invest in making some of

those very fragile societies a little bit less vulnerable.

Because we are kidding ourselves, I think, if we conclude that somehow, you know, our self-interest requires us just to focus on challenges at home.

There’s going to be a spillover from, you know, the moment when that wave hits in those countries and all of us are going to have to deal with it. It

is better for us to try to invest what we can now.

AMANPOUR: It really doesn’t bear thinking about and will be faced with that pretty soon. But I want to end on a part of the Middle East. I mean,

you know so well and that’s Israel, obviously. And there’s this beautiful picture that’s been making the rounds of a Jewish doctor and a Muslim

doctor facing their different directions to say prayers and taking a break between their joint efforts to save lives and coronavirus lives.

But on the other hand, there’s also a power grab by Prime Minister Netanyahu. He’s managed to consolidate his power even though he didn’t win

the election. And Benny Gantz, his opposition, has essentially given up his choice to form a government and decided to go into an emergency government

of national unity. And Netanyahu has closed down courts and everything, which presumably, you know, inoculates him from the corruption trial that

he was about to face. What does this all mean for that part of the world?

BURNS: Well, I think in Israel, I mean, the pandemic has provided, in a sense, of a new political lease on life for Prime Minister Netanyahu. He

can fight the criminal indictments that have been brought against him from the prime ministry assuming this government is formed, he can begin to

rehabilitate his political image. It’s not for nothing that, you know, a lot of Israeli political commentators call Netanyahu the magician.

But — and you’re right, what you mentioned at the outset, you know, about a recognition of the shared humanity on the part of both Israeli and

Palestinian physicians, maybe this will be a reminder of the importance of renewing an effort to build some kind of political reconciliation.

But, you know, at this moment, it seems as if, you know, what’s being strengthened is an attitude in Israeli government that doesn’t see the

urgency and trying revive a two-state solution.

AMANPOUR: Bill Burns, thank you so much for joining us. Thank you very much, indeed.

BURNS: My pleasure.

AMANPOUR: And now, we shift from geopolitics to zero in on the most intimate impact of this crisis. Stay at home orders mean that individuals,

couples and families are either happily ensconced together or trapped.

The United Nations warns that rates of domestic violence will likely increase, particularly against women with families locked down at home.

Here to talk about the good, the bad of social distancing and self- isolation is Dr. Orna Guralnik, psychoanalyst and host of SHOWTIME’s documentary “Couples Therapy.” And NYU professor and sociologist, Eric

Klinenberg, who’s written extensively about relationships and social isolation. And his new book is called “Palaces for the People.”

Orna and Eric, thank you both very, very much for joining me.

Let me just ask you both to weigh in on what you’re hearing. Orna first, because you actually have clients, patients and couples therapy. What are

you hearing from the people who you still interacting with, albeit at a distance presumably?

ORNA GURALNIK, CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST, “COUPLES THERAPY”: Yes. I’m interacting with people from home, but I’m interacting with everyone, no

one has dropped out. I mean, people need help.

I’m hearing extreme levels of anxiety. You know, some of the anxiety is rational, obvious. I mean, we all know why we’re anxious and some of it —

I mean, you’re talking to an analyst. So, some of it has more to do with unconsciously motivated fears. And this kind of irrational fears are very

up on the surface.

To start with, we are not used to this state of lack of definition that we’re forced into by being quarantined. You know, in our everyday life, our

environment structures us, we move between different spaces, different temporalities, home, taking the train, going to work, school, picking up

our kids, running, going home. All of these provide us with a certain level of definition and force us to kind of keep switching perspectives

throughout the day. And now, suddenly it is all collapsed. We are under conditions of quarantine. And we’re in an altered state.

So, our capacity to reflect, to move through things, to take different perspectives is compromised. Now, the other thing that it’s forcing us into

is living very closely with other people, to — for those of us who are living with other people. And that’s causing certain kinds of basic, again,

boundaries and definitions to liquidate because we are spending all day long with the people we often are apart from, which is exacerbating a whole

bunch of other kind of family couple interpersonal dynamics, which I can get into if you want to.

AMANPOUR: Yes, I will. Yes, we will get into it in a second, Dr. Orna. But let me move to Eric Klinenberg for a minute and I’m going to come back to

you to get more specifics.

Eric Klinenberg, I said you’d written book, “Palaces for the People,” but you’ve also written and “Going Solo.” As a sociologist, what are you seeing

now in terms of, you know, who’s benefiting, who’s not in the relationship category and in the — you know, in the love or not love department right

now?

ERIC KLINENBERG, AUTHOR, “PALACES FOR THE PEOPLE”: Well, this is a very hard time to be living alone. But I think as we just heard, it’s also a

very hard time to be living together. It is a hard time to be living and we are all kind of reeling from this transformation.

So, on the together side, I think one of the big struggles here is that the thing we want when we’re facing major stress, the kind of comfort and

security that we get from an intimate partner is often tied up in our physical intimacy, the closeness of touching and embrace that means so much

and that can get us through something physically has suddenly taken on a new meaning.

I’m very already hearing from people who are concerned about catching this virus and that anxiety penetrated into their interactions with people in

the household as well. And so, suddenly there’s a fear of the very thing that gives us comfort at other times. And, of course, there’s another

couple dynamic that I’ve been observing, which is that in some cases, one member of a couple takes on a lot of the emotional responsibility for

carrying the anxiety and is the person who is most worried about the touch points with the cashier or the delivery person. What happens on the

shopping trip?

Whereas, the other person winds up being the kind of voice of permission but maybe also denial and that can set up a kind of conflict or tension

inside a relationship that I think a lot of people are enduring right now.

On the side of people who are living alone — sorry. On the side of people who are living alone, we have more people than ever in the world on their

own these days. And in the book, I wrote I kind of emphasized all the ways in which we use our shared gathering places, our social infrastructure of

libraries and senior centers and parks and playgrounds to build those connections in real life so that you can live alone and not be isolated and

lonely. But now, unfortunately, so many of the people who are living alone are feeling the burden of this isolation and the kind of mental health

issues that are accumulating as we adjust to this very solitary mode of living are very difficult.

AMANPOUR: I want to come back to you, Eric, in a secone, but first I want to ask Dr. Orna, because I’m going to play a little bit of a clip from your

SHOWTIME series “Couples Therapy”. And this is — I mean, essentially, it goes to the heart of some of the really difficult things that can come up

to the surface when you are in these moments of crisis and especially when you’re trapped, and some of it is about past trauma, things that you have

gone through in your life before that potentially come up to the surface. So, let’s just play this clip and we’ll talk about it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: What’s your history with letting things happen that has taught you, I better drive this life really hard otherwise what?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: You know, growing up in the household that I grew up in, there was not a lot of control.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Tell me.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: My mother was very young when she had me and her escape was probably, you know, getting high. And so, now, you couple that

with my father who was there at the time who was also getting high, who’s young also.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: And did they stay together?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: For a long time.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: But it was a volatile, violent, toxic, unhealthy, think of all of those adjectives, environment.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Right.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, Dr. Orna Guralnik, I mean, one might think that’s got nothing to do with this but of course it does, right? I mean, here you have

a woman who’s feeling all these issues coming up from the past and perhaps it — this idea of control sort of matters now that they’re trapped in a

place with or without somebody else.

And also, what happens if you had that, as a child, and you’ve got children in the household, what are children going to be learning from you? So, tell

me about why that clip is important to sort of analyze at this point.

GURALNIK: I love this question. And it builds a little bit on what Eric was saying. But, you know, people have different ways of organizing

themselves in response to such intense affects and anxiety that are coming up with this virus.

You know, I mean, you could categorize it into those that like to disassociate, take distance, rationalize, minimize and look to facts and

those people tend to like to some distance around them and some distance between them and the source of the agitator. And it will obviously depend

on their history, their personal history and sometimes even transgenerational histories because a lot gets kicked up with this kind of

large, global pandemic.

And some people might need to go right into it and go into the heart of the trauma and explore all the nooks and crannies of what could happen, what

kind of catastrophe should we be protecting against. And they may need to go right into it and to — and often, they want more closeness. And what

people are facing in this moment is the challenge of how do you live with another.

You know, I was listening to the earlier part of what this program is and to your talking about large-scale politics, but these large-scale politics

live inside the tiniest and most intimate of spaces, which is how do we live with otherness? How do we create a certain kind of mini political

system where both ways can survive and get what they need? Can the relationship actually provide a system, a holding environment, where

different needs are being met? And that is the big challenge and it’s always a challenge. And under this kind of situations of extreme stress it

will really come to the surface.

AMANPOUR: So, Eric, let me can you, because I just will read you a few statistics, because all this also begs the question, what happens?

And cases of domestic violence and child abuse may be rising. The U.N. is warning that domestic violence cases are surging. In Hubei province, which

was the epicenter, they said that domestic violence reports to police more than tripled in one county during the lockdown in February.

And some countries, France, Spain, others, they have had to sort of agree that women who feel threatened, for instance, and in danger are able to

come out of isolation and try to seek help.

They have given them special codes to try to sound the alarm to get away from potentially their abusive partner. And there’s been a domestic

violence murder in Spain.

Just describe, you know, what this might mean for very many women and children around the world right now?

KLINENBERG: Well, this is an issue of tremendous concern, of course.

And let’s face it. Women who are the victims of domestic abuse and children who are the victims of domestic abuse feel trapped in ordinary times. It is

all the more difficult to find a way to get out at a moment like this.

And what compounds the situation is that it’s in moments of high stress, of high tension, when men start to lose income, lose jobs, lose control, lose

their sense that things are stable, that they become more likely to act out aggressively and violently towards the people around them.

And so I think we have every reason to be worried about a spike in cases of domestic violence. And the fact is, around the world, places that are open

and accessible, safe spaces for women and for children, are crucial at providing a release from situations like this.

If there’s a gathering place where you can get companionship and social support, and seek attention and care, that significantly increases your

capacity to deal with a violent situation at home.

And, of course, that is exactly what is shutting down around the world right now. And so I think it’s urgent that we come up with some other way

of calling attention to this need and this issue and find forms of support, so that people don’t feel as trapped as they might.

AMANPOUR: And, indeed, as you alluded, in many, many times of crisis, war and this kind of crisis, domestic violence does actually spike.

I want to — Dr. Orna, let me ask you something, because there must be an upside to this. It can’t all be stress and difficulty. I mean, there must

be some young couples who are delighted to be at home together, maybe newlyweds or about-to-be-weds or something.

Can this actually help in certain couples?

GURALNIK: Absolutely.

Of course, there are the situations that violence and other extreme situations bring people to the worst in them. But this situation is also

bringing — I’m seeing a lot of moments of grace and people actually — a certain kind of veil has lifted, and people are coming to terms with their

vulnerability, with their mutual dependence, in a way that is actually beautiful.

I’m seeing couples being able to work through issues that they couldn’t before because they were too embedded in their daily grind. And it’s like

this moment where you — suddenly, something is lifted, and you can see life for what it is.

I mean, humanity is always trying to understand what it is that we’re here to do, right? And this is a moment where we can step out of the daily

habits and ask ourselves very important questions. What are we here for? How is this relationship going to support us? How are we part of a bigger,

larger community? What is the task here?

I mean, we’re not doing things — most of us are not self-quarantining for ourselves. We’re doing it for our community, for a large-scale community.

And I think that’s bringing out some beautiful things in people.

Of course, people go to the edge and kind of what we call interpersonalize their inner conflicts, and they get into tiffs and blame each other. But

I’m finding that people very easily hook back into the larger issue which is at hand, which is that we are trying to be in this together.

What we’re doing right now is not just for ourselves. We’re locating ourselves in a large-scale community. And I think that is big, and it’s an

important moment to embrace and to take inspiration from.

And I think many people are up for the challenge.

AMANPOUR: I think that’s really an important point.

And, finally, Eric, Bloomberg is reporting that, in China, there’s a surge in divorces as couples come out of lockdown. You have also written modern

love. You have written about online dating and the way modern dating and coupling goes on.

What do you think is going to be the fallout from this crisis on dating and online dating going forward?

KLINENBERG: Probably, online dating is booming at the moment, but it’s the online part of it, and not the dating part that’s really happening.

We do have some technologies that allow people to be physically distant and to — and to try to build a connection. And so all of us are getting adept

at using technology in this way.

I think what we’re learning, though, is that, for the most part, this way of being together is not a very good substitute for being together face to

face. And so what I expect to come from this over time, when we get to the other side of the pandemic, is that we will begin to appreciate the value

of things that we have taken for granted for some time, our gathering places, the physical features of our environment, our social

infrastructure, that gives us a chance to come together and enjoy social life.

And my sense is, one of the things about this event is, it’s helping to reveal just how much my fate is linked to your fate, just how much of a

value there is on providing strong public programs and services that give us all a chance to live well, because I know now that when my neighbor gets

very sick, and if my neighbor has to go to work when they’re sick, because there’s no paid sick leave, say, that makes me much more vulnerable.

It makes the collective much more vulnerable. And so I guess one thing that I would expect at the end of this is a moment where history switches a

little bit, and we began to reinvest in each other, and in the kind of collective project that makes the world a little better than it is right

now.

So, although this is a horrific and scary moment, and I think we’re just at the beginning of this, there is a possibility that, through this process,

we learn to discover the better version of ourselves and do something to get out of this very dire situation we’re in right now.

AMANPOUR: And let’s hope it lasts.

Thank you so much, Dr. Eric Klinenberg and Dr. Orna Guralnik. Thank you very much indeed for joining me this evening.

Now, our next guest is top Republican strategist Stuart Stevens. He is known for advising key campaigns, like Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential bid.

And he’s now written a powerful mea culpa for “The Washington Post,” placing the blame for President Trump’s failed response to the coronavirus

squarely on the shoulders of all Republicans.

Our Michel Martin talks to him about his new book, which is called “It Was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump.”

Stevens says he’s given up any hope of the party changing any time soon.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN: Stuart Stevens, thanks so much for talking with us.

STUART STEVENS, REPUBLICAN STRATEGIST: Thank you. Great to be here.

MARTIN: I don’t think it’s a secret that a lot of members of the Democratic opposition, certainly a lot of independent scientists, and,

frankly, a lot of analysts around the world have been critical of the way the Trump administration has handled this current crisis.

And you wrote a piece, a very provocative piece, I have to say, for “The Washington Post” saying: “Don’t just blame President Trump. Blame me” —

I’m reading here — “and all the other Republicans who aided and abetted, and, yes, benefited from protecting a political party that’s become

dangerous to America. Some of us knew better. But we built this moment and then we looked the other way.”

Those are some pretty strong words. So let’s take it step by step.

First of all, why do you say blame you?

STEVENS: Well, look, for 30 years, I have been helping elect Republicans.

I have elected, helped Republican governors and senators in over half the country. So I think one of the principles of Republicans used to be that we

believe in personal responsibility. And that’s totally gone out the window now. We’re against personal responsibility.

But it seems to me, if we’re going to return to that, the first step is personal responsibility. And I can’t say this just happened. I was part of

it. I was deep into the machine, working five presidential campaigns for Republicans.

So I was there. I saw it. I would like to have done things differently in retrospect, but can only move forward.

MARTIN: Let’s talk about the coronavirus pandemic specifically.

How are your observations about the state of Republican Party relevant to what’s going on now? What’s the connection?

STEVENS: Well, I think the Republican Party has failed tremendously on this.

The idea that, somehow, when you look at these polls, that more Republicans aren’t believing the reality than Democrats, it’s insane. And it’s because,

when Trump is out there saying crazy stuff, there’s really nothing you can do about Trump.

But you have to go out and tell the truth. And Republican leaders should have been out there earlier. It’s just — I look at this chloroquine as an

example. And it means something to me because I had a very, very bad case of malaria. In fact , I wrote a book called “Malaria Dreams,” where I took

chloroquine.

So the idea that this very powerful, potentially dangerous drug has somehow become a political issue is just so sort of a perfect little metaphor for

our moment. I mean, we have pretty safe drugs in America because we have a system that works.

So, somehow, we’re saying we shouldn’t trust the FDA, that we should listen to Donald Trump or Sean Hannity about what drugs to take? I mean, that’s a

short walk to Jim Jones.

MARTIN: But how do you see the state of the Republican Party, as you see it, affecting the government’s ability to deal with this crisis?

STEVENS: What we most need now in these moments of crisis is a sense of what can be agreed-upon truth.

And Trump is and the Republican Party has assaulted the concept of truth like nothing else in our modern politics. So, just at the moment when we

want — we need to believe someone, we need to believe experts, we have had this unprecedented assault on what are facts, I mean, talking about

alternative facts.

And I think that’s incredibly dangerous. I mean, it is what happens in Russia. It’s what happens in totalitarian societies, where you believe the

government — it’s “1984.” Who do you believe? So I think that, in itself, we’re sort of reaping this terrible sowing of mistrust among all our

institutions.

MARTIN: There was this recovery bill. It was passed by enormous margins.

Does that suggest anything to you, that perhaps the Republicans are able to work with Democrats, that the parties are able to work together on recovery

efforts?

STEVENS: I think there was a unity of fear, a unity driven by fear.

I thought it was very positive that that passed 97-0. I think that’s the sort of thing that begins to reinstall — reinstill faith in government,

which is critical at this moment.

I think it’s going to be woefully inadequate. I’m personally — and I’m no expert — but a pessimism on where this is going. So I thought that was

positive, yes. I think it would have been very negative had that passed by party-line votes or one vote or two votes. So I put that in the positive

side.

Look, these are not dumb people in the U.S. Senate. They can read, and they understand math, and they can look at this, and they’re all talking to

medical experts themselves. So they may not go out there and contradict Trump every day, though they know they should.

But when it comes down to it, they know they had to vote for something that would help people, if, for nothing else, to save their own skins, because

this thing is going to move out of New York, I think, into rural states very quickly. You see it Louisiana.

And I look at my home state of Mississippi, and I have very foreboding feelings about it. I mean, you have a collapsing for many, many, many years

rural health care system that much has been written about, and little done about.

You have the most unhealthy collection of citizens in the nation. And I think it’s a potentially catastrophic mix. Hopefully, it’ll get slowed down

enough to be able to take care of it.

MARTIN: How did this start, in your view? How did this whole fixation on elitism, this turning away from science and from fact, how did this, start

in your view?

STEVENS: Well, in my view, the original sin of the modern Republican Party is race, because if you go back to Eisenhower, in 1956, Eisenhower got

almost 40 percent of the black vote.

You go to go to Goldwater, that dropped to 7 percent. And it never really came back.

So, for the last — since ’64, Republicans really have been marketing to primarily white voters. So, what does that mean? It means you get really

good at a very homogeneous group of voters.

So it used to be the largest group of white voters were non-college- educated white voters. Now, that’s declining, but it’s become this sort of belief in the Republican Party that, somehow, to connect to these voters

who are less educated, that we have to pretend that education is bad.

And I don’t think it used to be that way. I mean, Roosevelt seemed to get a lot of working-class voters, and he was very well-educated. And he didn’t

go out and attack universities. And it’s completely phony.

I mean, you have some of the best-educated people in the world, like Ted Cruz or Senator Hawley from Missouri, talking about elitists. I mean, it’s

ridiculous.

But it becomes sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy. I mean, we actually have now this belief that is I think broadening that college are places that

indoctrinate students in some left-wing philosophy.

And history will tell us, any time you have a movement that attacks education, be it the Red Guard, nothing good happens. We should value

education and aspire to education. And that’s, I think, a dramatic wrong turn the country has — the Republican Party has taken.

MARTIN: Well, why did you participate in this all these years?

STEVENS: Well, that question really led me to write this book.

And it’s a very troubling question to me, and I don’t really have a good answer. I think that, when you’re involved in something like this,

particularly on the end of politics — I was in the campaign part of politics. I never worked in government.

So I was really about winning. And, to be honest, I was really good at winning. I won more races than just about anybody out there, helped in

races, more.

And there’s a certain intoxication that comes with that. You don’t really question it. I found, after the Romney campaign, where we lost — I worked

for the Bush campaign, where we won — that I did a lot more reflection on why we lost than why we won.

And when you win, you just kind of roll into the next race. And it is tribal. You have a comfortable place in the tribe. You’re well-compensated.

People know who you are. You’re good at what you do. There’s something about that is just very comfortable.

MARTIN: Did you not any see of these things before, when you were working with some of your candidates?

Like, one of the — I can’t help but notice that some of the candidates that you helped get elected have been on the forefront of some of these

movements. I mean, one of your congressional candidates was one of the top sort of defenders of President Trump during the impeachment hearings, OK, a

very aggressive defender, was very much pushed out front because of her aggressiveness.

Why do you think you see things so differently than they do? I mean, did this never come up when you’re having all those hours together plotting

strategy and figuring out what they’re going to do?

STEVENS: Well, you know, there was sort of an agreement that there was a set of beliefs, that we might disagree on this or that issue, but there was

a sort of fundamental set of beliefs.

So, what would that be? Personal responsibility, character counts, deficit matters, strong on Russia, pro-legal immigration. I mean, Ronald Reagan

announced in front of the Statue of Liberty. He signed a bill to make everyone in the country before 1983 legal.

So, when you had those sort of belief in that set of core beliefs, it made differences on issues less dramatic, because everyone’s going to disagree

on issues, OK? I mean, sit down at Thanksgiving dinner, I don’t agree with my family on everything.

But, look, it’s easy not to be self-reflective.

MARTIN: Well, I’m going to go back to something you said at the beginning, though, is race being the original sin of the Republican Party.

Even Ronald Reagan, who was a person who obviously was a person who deeply liked people and had a great sympathy for people, I mean, he had a campaign

announcement in Philadelphia, Mississippi, I mean, please, where three civil rights workers were viciously murdered.

And George H.W. Bush, I mean, I don’t think anybody would think that man’s a card-carrying racist, but then here he is with the Willie Horton ad.

So, the fact of the matter is, race has been used by the Republican Party for an awfully long time. And my question is, why? I mean, does nobody

think that would be destructive at some point? Nobody would think that would become kind of a tiger whose tail you can’t — you can’t hold on to?

Nobody ever thought that?

STEVENS: What became the sort of truism inside the Republican Party that the reason African-Americans didn’t vote for Republicans is that

Republicans just weren’t good at talking to African-Americans.

And I write about this a lot in my book, that it was a communication problem, that they just didn’t understand what we were saying, that there

was a deep entrepreneurial spirit in the African-American community. They had this deep sort of love of family, a lot of them were culturally

conservative. We could bond with them. We just had to learn how to talk to them.

And I think that was a complete myth. I think African-Americans understood what Republicans were saying very clearly. And they responded.

And I think there’s been this reluctance to address the core issues of sort of policy that have not favored African-Americans that Republicans still

continue.

So, what is our solution? Our solution is payroll tax cuts, when many people aren’t benefiting by that. So, I think it’s a whole combination of

issues that really goes to a reluctance to address fundamental policy issues that are not appealing to many of those who are the most

disadvantaged in our society.

MARTIN: And now you have got, of course, the whole FOX News media industrial complex kind of organized around kind of the conservative media

industrial complex to amplify that message, something that…

(CROSSTALK)

STEVENS: Look at Lindsey Graham in the last week talking about how nurses, if they were paid $25,000 — $25 an hour, might not come to work, I mean,

in this bill.

Is there anything more insulting imaginable, the idea that some — it’s this sort of feeling that people don’t want to work. I don’t think that’s

true. I think people do want to work. And I think nurses — the idea that Lindsey Graham would go out and say that, it’s just one of these moments

when sort of — Michael Kinsley’s definition of a gaffe was when a politician tells the truth.

And that’s just sort of a classic moment of that. It just reflects a deep- held belief.

MARTIN: Well, why, though, do these candidates continue to get elected? I mean, presumably, there are nurses in South Carolina, right, who might

object to these comments? Presumably, there are medical professionals.

I mean, you have heard the president the other day in his daily briefings…

STEVENS: Yes.

MARTIN: … suggest that medical personnel were somehow hiding or hoarding or backdooring these medical supplies. Presumably, these are — some of

these folks voted for President Trump, which actually leads me to my question, which is, how do you explain the president’s current approval

rating?

I mean, it’s the highest it’s been since he took office. How do you understand that?

STEVENS: Well, if you look around the world, all of these leaders in these countries who have been besieged COVID-19 are doing well in polls.

I mean, in Italy, the government is at 70 percent, and they are dying like flies. I think that’s just a natural belief that we have to pull together,

sort of a reflection of foreign policy ends at water’s edge sort of thing.

I mean, we forget Bush went up originally after Katrina. I think that that is just sort of something that’s very — it’s not American, but we see it

across the world. I think it’s very human to want to pull together. And Trump is the president, so you want to support the president.

But at the same time, you see him losing to Biden by almost 10 points in these polls. So I don’t really think it means anything.

MARTIN: Do you have any hope that enough people agree with you that a change will occur?

What would you like to see going forward?

STEVENS: I have pretty much given up hope on that.

I mean, I think that we saw, in impeachment, the inability for anyone but Mitt Romney to really look at the truth. And there’s no question that if

Barack Obama had been accused of this and had done this stuff, they would have impeached him in a second.

So the idea that the Republican Party as an institution is going to reform itself based on any sort of standards of principle or morality, I think we

just have to abandon. We can’t believe that.

I think the only thing that will change the Republican Party is utter terror. And that terror will come when they start to lose. So, of the

Americans under 15, the majority are nonwhite. So there’s some reason to believe that those 15-year-olds are going to become 18-year-olds and remain

nonwhite.

And that’s sort of like a very, very dark sign for the Republican Party, because it has really sort of embraced becoming a white grievance party, in

a way that would have been unimaginable to me not very long ago.

So, I think, when the Republican Party can’t win anymore — and we have lost seven out of the last eight popular votes. I mean, I worked for Bush

in 2004. It’s last time since ’88 that we won the popular vote.

So I think that only losing is going to force the party to change.

MARTIN: Stuart Stevens, thanks so much for talking with us today.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: It’s a really powerful reminder that an assault on science and fact and evidence is so dangerous, especially in times of crisis like this.

And finally tonight, Italy held a minute of silence for its coronavirus victims. Towns and cities throughout the country played “Taps” and lowered

their flags to half-mast in solidarity to mourn over 10,000 people who’ve lost their lives there so far.

But, despite the relentless cycle of death, or maybe because of it, there are so many people trying to spread joy as an antidote to this virus.

These twin boys in Sicily put on an exuberant violin concerto over the weekend while in quarantine.

And we leave you with their rendition of Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida.”