Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, lockdowns have hit every economy deeply. But what if there was a way to save lives and limit economic disruption? Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Romer and president of the Rockefeller Foundation Dr. Rajiv Shah advocate for a data-driven quarantine and massively scaling up testing, as you heard Gary Cohn say, to allow a gradual return to work. Dr. Shah was head of USAID for President Obama and led its response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. They both tell our Hari Sreenivasan why a clear policy on testing is crucial to revive the economy, something they wrote about in their joint “The New York Times” op-ed.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN: Raj Shah, Paul Romer, thanks so much for joining us. First, the big picture of the plan that you’re trying to lay out, for people who didn’t read the op-ed or haven’t read the Web site. Paul, why don’t you talk about kind of the economic consequences and, Raj, the sort of medical ones that you’re both trying to address?

PAUL ROMER, NOBEL LAUREATE IN ECONOMICS: So, we are all committed to saving lives. What Raj and I are saying is, there’s a way to save lives that’s much less costly in terms of disruption and lost economic output. And the key to that alternative strategy is, instead of trying to put everybody into isolation or a large fraction of the population into isolation, what we need to do is find the people who are infectious and put them into isolation. And then we can, with confidence, let everybody else return to daily life. And we have to do this gradually, starting from where we are. There are people already at work, so start by testing and isolating them, before we start to send new people into work. But, if we move quickly, we can much quicker get back to more normal economic activity and avoid the just hundreds of billions of dollars we are losing every single month because of the economic slowdown.

SREENIVASAN: Raj, balance that need for restarting the economy. How do we do this in a safe way?

DR. RAJIV SHAH, FORMER ADMINISTRATOR, UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT: Well, the strategy we’re putting forth is one where we massively accelerate access to testing, in particular, basic diagnostic testing, so we can identify who has COVID-19. And they can manage their quarantine processes, and others can go to work. And the reason that is so important is, we’re seeing, from Singapore, South Korea, Germany, lots of other examples of both widespread testing making a difference in restarting economic activity, and, frankly, the risk of reemergence of the pandemic over the course of the next 12 to 18 months. This is not something that’s just going to be solved in the next few weeks. And so either we shut our economy down, off and on, in a rather unpredictable manner over a 12-to-18-month period, or we have widespread access to testing, allow people who are not infectious to be active in the economy, and protect those who are more vulnerable through very targeted data-driven quarantine, contact tracing and management efforts.

SREENIVASAN: Why are we not testing the way that you have described? I mean, it seems pretty logical now. Obviously, there’s a shortage. We’re all aware of some of the shortages. But why is it structurally that we are not testing the way you two are advocating for?

SHAH: Well, I think there are three major roadblocks right now. The first is, you need capacity and physical infrastructure and people to be trained in collecting samples and being part of a testing scale-up. We’re seeing that start to evolve in certain cities and in certain states, where they’re investing in that as an approach, but it’s about building a real infrastructure to actually make sure anyone can access testing. We have heard rumors about certain partnerships that don’t seem to have materialized fast enough. But that’s now starting to scale up. But it’s a major, major infrastructure build-out that has to be done with NGOs, with fire departments, with schools, with wherever you can offer testing access, with companies in their parking lots, et cetera, in a way that makes it really broadly accessible. I think a second is that the traditional mechanism of acquiring test kits that have been approved, sending the data, the material back for processing to labs that are part of the reimbursement stream of the particular health center that does the testing, people are doing what they always do, and doing it in a way where they’re going to get reimbursed based on the complex reimbursement system we have in place in the United States. And we need to rethink that. We need a different approach, so that people can use university labs that might have more capacity right now than lab — Quest and — than LabCorp and Quest. But that requires a change. And I think the third is materials and supplies. Right now, if you’re a mayor trying to get access to the Abbott test, you probably need a special phone call to the CEO of Abbott in order to get in line. And you just can’t have hundreds of mayors and 50 governors scrambling like that. There has to be a procurement strategy, real resources committed to making sure the supply chain is big enough and broad enough to support scaling at the level we’re talking about. I think all three of those things are all critical elements of a national testing strategy to solve this problem.

SREENIVASAN: Let’s talk a little bit about the numbers here. How much money would it cost the U.S. government to try to implement your plan to try to accelerate testing on this significant scale?

ROMER: Yes, I think $100 billion a year is a good number for us to aim for. And I think it’s a small number compared to what we have been spending as part of these other stimulus and emergency measures. And I think it would be well large enough to cover the costs of this massively scaled-up scaled up testing program. I think we should remember, though, that this is an ongoing process. We can’t just turn this thing off when, say, it looks like the number of deaths is going down. So, we need to start planning to just spend this on an ongoing basis. I think it’s kind of like we spend $600, $700 billion a year on military defense. We should be spending $100 billion a year on health defense, because the biggest threat we have suffered, the biggest hit we have suffered has been on this health side, not on the military side.

SREENIVASAN: Given the state of government today, how likely is it to get that kind of funding approved for this specific task? Yes, we are writing $2 trillion bills, or we have already. Can this have a bipartisan consensus and can this get through?

ROMER: I think it can. I have spoken to a few people in the Congress. And their reaction was, my goodness, no one has ever even come to me and said, spend money on this. If you think about it, there are no lobbyists who are trying to lobby for just the greater good of the public. But if you explain to the legislators the value of something like this, I — they’re very open to it. And in terms of the mechanics to do this quickly, if the U.S. Congress said, we’re willing to allocate $100 billion a year, and then we give those funds in block grants, in proportion to the population, to the states of the United States for the governors to spend on testing, the governors could act on this and get this going, I think, very quickly.

SREENIVASAN: Raj, while you were at USAID, you oversaw the testing system that happened in during the Ebola crisis in West Africa. What did you learn?

SHAH: Well, the most important thing I learned leading the West African Ebola response in 2014 was, testing was absolutely critical to getting both an effective response and allowing for the confidence to emerge so that people could reengage in the economy. We saw a 30 percent loss of output in West African countries that were affected. In that context, that moved people back under the extreme poverty line. It created massive amounts of hunger and human suffering. And it was absolutely tragic. And the thing that got that turned around was getting testing access from a seven-to-eight-day process of finding a place, getting a blood sample, getting it sent out, getting the results, and maybe you had access, maybe you didn’t, to knowing everyone in the region could get a test and get a result within four hours. We had U.S. military personnel flying lab samples on helicopters. We deployed bioterror labs throughout West African countries like Liberia to make sure there was broad-scale access. We trained thousands of community health workers in wearing protective equipment, so that they could be on the front lines of collection. It was a massive effort focused on that number, the number of hours it takes to get a test result. Once we had it under four hours, people confident again. They say, OK, if I feel anxious about it, I — and I have some symptomatic reason to feel that way, I can get access to a test and a result, and I will know. Without data and without testing being at the core of that data, it’s very hard to have the confidence you need to just reengage in your community, to get out of your house and to do things that are economically productive and are going to put food on the table for your family.

SREENIVASAN: What should the threshold be, how many days? And what is the data point that we’re looking for to be able to try to resume some semblance of normalcy in life, or how does this roll out? Does it happen in different phases?

SHAH: Well, the scale — a national strategy and a national investment to scale up testing has — is an immediate priority. It has to be the thing we do right now together, public and private, industry and science, government at the federal, state and local level, all working together. And that’s what the Rockefeller Foundation’s advocating for and building partnerships to execute. The reality is, right now, we know that, at a minimum, front-line health workers, they should all get testing, regular access. Both Paul and I have front-line health workers in our family. My sister’s a doctor. They still don’t have consistent access to testing, despite very clearly being both at risk and being essential to the actual health response. We should expand the definition of essential workers to include those who are taking more risks to allow this economy to function, even when there is a widespread quarantine in place, including gig economy workers that are delivering your food and people who are supporting public transport systems to stay viable and open. And then, as we start to hit the bigger numbers of getting millions of tests executed a day, then we believe you need to expand this much more broadly, so that we can reopen parts of the economy in a more sustained and predictable manner. And that’s very important. That goes beyond really thinking of this as purely a health response. And it goes to recognizing that you can’t just keep the economy operating at $300-$400 billion of GDP loss on a monthly basis, relative to being open, for very long without really crushing the ability of millions of American families to just get by.

SREENIVASAN: Well, markets hate uncertainty, right? And they also don’t like to write checks that might never end. When right now the scientists don’t particularly know whether I could get reinfected with this if I have had it once, if there could be a second wave and a third wave that might come seasonally, it might come — between now and when every person in this country could get a vaccine if they wanted to, there’s a lot of uncertainty. So, economically, are we — should we be preparing for that kind of a up- and-down cycle, where each piece of new information swings the markets 1,000 points in one way or the other?

ROMER: I think you have just hit the nail on the head. The biggest cost to the economy comes from uncertainty. We could get by — we survived with a lower level of output. If we had to give up 10 percent of output permanently or devote it to something like this, we survived at a time when our GDP was 10 percent lower. We could go back to that. We could — but what we can’t live with is uncertainty about, if I start paying my workers, I start buying inputs for my restaurant, what if I get shut down with a lockdown again in a week or a month? Or should I start investing in the factory production line to restart the production of cars or other goods? Should I continue work on the building that we were building for people to live in? So, uncertainty is really our greatest problem. It’s like what Roosevelt said, that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself, and so that what we need is a policy which we can stick to that removes all of that uncertainty. And this policy of test enough so that we can put into quarantine about 70 percent of the people who are infectious, that, with certainty, will get us below this R0 equals 1 threshold. And it will mean that any new infections that come into the U.S. will quickly damp out, and we can all count on a return to life as we knew it.

SREENIVASAN: Paul — I guess this is a question for both of you, but I will start with Paul. What happens if we do not roll out something like the plan that you are talking about?

ROMER: I think the baseline business as usual will be maintenance of lockdown, until the pressure becomes so strained, and also until the number of deaths starts to go down, so people feel relieved. But then, as we release lockdown, we’re likely to see reemergence, just like we have seen in Singapore. So the baseline is, unfortunately, on-and-off lockdown for 18 months, and it could be more. It could be 24 months. And, as I said, that will kill any possibility of investment that will be so critical for recovery. And I think we need to think carefully about not just the economic costs of this, but what kind of political and broader social costs might we see? We’re looking at disruption the scale of or worse than the Great Depression. And we know that that had profound and very harmful effects on democracy, on social life, on geopolitical stability. So the risks here, I think, are really extraordinarily large. Now, I’m still an optimist. If we just spend some money, we just do the kind of testing we need to do, I’m totally confident that we can do that. But the risks, if we do nothing, are, I think, bigger than they have ever been in my lifetime. And just go back to the optimism. In the United States, we make 300 million soft drinks every day. A country that can make 300 million soft drinks can do 30 million tests a day, if we just set our minds to it.

About This Episode EXPAND

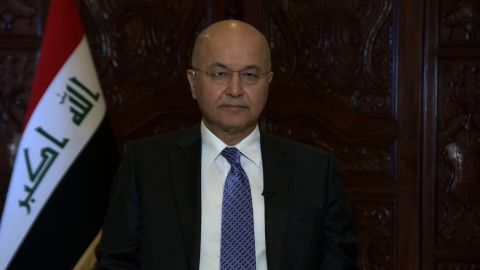

Gary Cohn, President Trump’s former Chief Economic Adviser, discusses what reopening the U.S. economy will look like. In an exclusive interview, Iraq’s president Barham Salih explains his country’s response to COVID-19. Paul Romer and Dr. Rajiv Shah tell Hari Sreenivasan about their plan for a testing and data tracking program that will get people back to work before job losses become permanent.

LEARN MORE