Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

What’s the pathway out of the great economic depression and not just for the 1 percent? I ask the head of the IMF.

Then, our relationships with lockdowns and under lockdowns. Tens of millions tune in for therapy with Esther Perel. We get her top tips for

couples, quarantine and more.

Also, ahead —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PEGGY FLANAGAN, LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR, MINNESOTA: 40 percent of Americans don’t realize that native American people still exist.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

Minnesota’s lieutenant governor, Peggy Flanagan, talks to our Michel Martin about the devastating impact of coronavirus on Native Americans and her own

tragedy, losing her brother to the disease.

Plus, still making music. Composer, Andrew Lloyd Webber, pulls back the curtain on his lockdown performance.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour working from home in London.

Nearly half a century of continuous economic growth in China is over. New figures show it contracting 6.8 percent in the first quarter of this year,

according to the Chinese government itself. Now, with the global economy so heavily dependent on China, this exposes an immense challenge ahead and it

explains why President Trump and other world leaders are so eager to restart their own frozen economies.

This week saw unemployment continue to soar in the United States and around the world. And the question for everyone, will this all change after

lockdowns are lifted or will they be a much longer-term impact?

With me now is Kristalina Georgieva, head of the International Monetary Fund. The IMF which oversees member states economic development and

crucially lends money, predicted this year, the global economy will experience its worst recession since the great depression.

Madame Georgieva, welcome to the program.

KRISTALINA GEORGIEVA, MANAGING DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you, you know, you have said in the aftermath of these lockdowns that this is kind of unprecedented. Explain to me the

picture that you as an economist see, that everything is sort of coming to a head in a tsunami-like effect.

GEORGIEVA: Well, this is really a crisis like no other. First, because it is a combination of pandemic and economic crisis in which to fight the

pandemic, we have to stop the economy. And at the time when you need more revenues for your health systems and to help workers and firms, you

actually have less. And that leads to very massive action to keep the economy virtually on life support. Fiscal action, monetary policy action.

Very, very unusual. Never happened before.

But let me tell you two more things there, Christiane. It is a truly global crisis. We haven’t had a global crisis when the whole world is affected at

the same time and goes backwards. And on top of it, uncertainty is not your usual economic uncertainty of how demand and supply would interact. It is

uncertainty about a novel virus. We don’t know what it will do. Epidemiologists don’t know what it would do. And that added uncertainty

makes it all so very complicated.

AMANPOUR: And what we have learned, even for sort of, you know, nonexperts like myself, ordinary people looking at the economy, it’s sort of like a

religious thing to say the economy hates uncertainty. So, so you have just stated that that’s what we’re living in right now, uncertainty.

But also, just to put it in perspective, you know, not so many months ago you were predicted economic growth saying that, I think, something like 160

countries would, this year, show per capita income growth. Now, you’re saying the opposite for 170 countries, their economies are going to

contract and about 100 have already asked you, the IMF, for help. I believe you have about a trillion dollars at your disposal for help. It sounds like

a lot. Is it for that much need all at once?

GEORGIEVA: What is needed now is to provide financial support to the countries that cannot, on their own, cope with this crisis and do it very

rapidly. At the IMF, we have taken early the decision to double emergency financing, meaning that this lifeline can last longer and the countries

certainly need it. But on top of it, we are looking into who is going to be affected most dramatically? The same way the virus hits people with weak

immune system the hardest, the economic crisis hits poorest countries the hardest.

So, what we have done is, together with the David Malpas, to call for that moratorium of bilateral official creditors. And luckily, what we have seen

is tremendous, just within weeks, a decision was taken. Very valuable. Because if the economy is standing still and you’re a poor country, you

sure cannot afford to pay back your debts. And we are looking into the next months of this crisis and we are telling the countries that can do more,

please step up right now.

And I don’t want to — I want to tell you one piece of really exciting news about solidarity. Yesterday, we had our governing body, the membership, 189

members of the IMF together. We said, we need $17 billion in concessionary sources to help the countries that are in most dire need. And within this

meeting, we got 70 percent of our ask. And I think this is an illustration that everybody understands how sober, how serious we ought to be in this

very unusual, unprecedented crisis.

AMANPOUR: OK. Well, that sounds, A, very good and hopeful and quite different as some of the other sort of lack of solidarity we have seen

around the world in some of these issues. But I do want ask you, you said a debt moratorium, debt relief, debt suspension., all of those things. But

you’ve heard the French president, Emmanuel Macron, is hoping that eventually it could lead to a cancelation of debt for these countries who

really, really, really will not be able to cope. And you’ve already, yourself, identified in Africa that I think something like half the

population of that continent faces losing their jobs. I mean, it is absolutely unthinkable.

GEORGIEVA: Well, first, my hat goes to President Macron for zeroing on — especially on Africa. He has plenty on his plate at home, plenty to be done

in the European Union. And yet, he has put forward a priority to support especially Africa, to support all poor countries but especially Africa and

rightly so.

And yes, the IMF and the World Bank are going to go country by country by country during this time of debt moratorium to identify where more may be

needed, where more actually debt relief, debt cancelation may be a necessity so the countries can go through this tremendous challenge. And

why do we need that? We need it because we have to beat this virus everywhere to be safe whenever we are. And obviously, countries that have

very limited resources, they cannot do it on their own, especially if they are sinking under the burden of debt.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Can I ask you something? You know, there is no playbook for this, what you’re facing. You have described it as unprecedented and

there’s no playbook. How do you get out of it, particularly when traditional areas of people, you know, believing like a strong China

economy means a strong global economy?

We’ve just said that for the first time in half a century the economy has contracted, 6.8 percent this quarter. How do you get out of this? Are you,

at the IMF, able to make a prediction of when there might be a resurgence, economic growth?

GEORGIEVA: So, what our prediction is that provided we beat the virus, then we would see a rebound, and it would be quite strong, especially in

2021. For the world this year, we predict the contraction of 3 percent minus 3 percent growth. But for next year, we predict 5.8 percent plus.

However, going back to the unusual uncertainty, all of this hinges on what happens with the pandemic. I for one believe that our scientists are going

to come up with vaccine and treatment. But if that takes longer or if the virus decides to go around the globe twice, then we may be in a much more

difficult place, Christiane. And so, how do we approach that at the fund?

We are saying we need to do three things. Number one, protect the health of people. Invest in the salaries of doctors and nurses and in hospitals

everywhere. Number two, build a bridge over this tremendous drop by spending as much as you can and then a little more so people are not going

to be desperate for food, firms are not going to start collapsing one after another. In other words, we are not going to scar the economy to a point

that it will be hard to then step on its feet. And in that, too, we have to also say very clearly, yes, spend more, but keep the receipts. We cannot

afford to have accountability and transparency taking a backseat in this crisis.

And, three, and three, prepare for recovery. Prepare for recovery. And prepare for recovery means identify what problems we are going to have when

we go on the other side. Debt would be higher. Maybe unemployment would be higher. I worry in particular for the social cohesion. If inequality goes

up, it would damage our society. So, let’s do what we can now —

AMANPOUR: That’s right.

GEORGIEVA: — to prevent these problems from happening.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you, finally, in our last minute. Do you — because this is the, worst — your prediction of minus 3 percent

contraction, is much worse than the 2008 financial crisis. And you saw what came out of that and the austerity that led to that. Nationalistic

populistic policies and politics and leadership around the world. Do you fear that this could trigger another wave of that kind of political result?

GEORGIEVA: I really hope that we would have the wisdom to balance our societies in a way that is fair. In other words, those who can contribute

more do that and there is a sense of unity, solidarity built in this crisis. We have one thing working for us that I — three months ago I

probably would have not seen in such a positive light, and it is very low interest rates. Zero, even negative. That gives us some space for

governments that are now borrowing more, building higher deficits, that that can be financed for some time until we get our house in order.

AMANPOUR: All right.

GEORGIEVA: And we also need to think of this crisis as an opportunity, Christiane. How can we boost the recovery in a way that it is green, it is

climate resilient in which we are thinking of gender equality? We make sure that women are treated as equal partners. In other words, can we, on the

other side, have a better, stronger society than on this one?

AMANPOUR: Yes. You know, that’s something that a lot of people have been talking about, hoping for and dreaming of. So, maybe this is a chance to

reset. We really hope.

Kristalina Georgieva, thank you so much, managing director of the IMF.

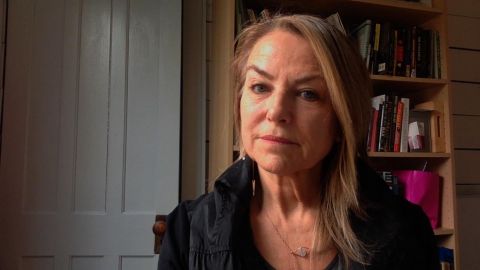

Now, economic fears, health anxieties and relationships all while trapped inside, that is just a few of the new pressures piling on all at once. So,

let’s get advice on how to deal with it all with the world’s favorite relationship guru, Esther Perel. She been talking to couples under lockdown

across the planet with her podcast “Where Should We Begin?”

Esther Perel, welcome to the program from Woodstock, New York.

ESTHER PEREL, PSYCHOTHERAPIST: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So, you have just heard the IMF director. I mean, you know, she’s talked about the worst and the potential, you know, best that could

come out of it. Are you hearing that kind of range of feelings, you know, from the people who are contacting you?

PEREL: I mean, you know, these economic realities that we have just described on a macro level, they literally enter inside the home of every

family, every couple and every individual. So, we have — I’m hearing a breadth of experiences when it comes to relationships.

What we have often known when it comes to disasters is that they function like a relationship accelerator, basically. So, if we just began dating, we

may suddenly be living together. If we were together, we suddenly decide it is time to have a child. We are aware that life is short, that mortality is

hovering around us. And so, some of us say life is short. What am I waiting for? Let’s have babies. Let’s be together. Let’s marry. And then, we have

other people say life is short. I have waited long enough. I’m out of here. I’m done.

And we know that there is always an increase of divorce and increase of children that come on the heels of this acute awareness that we can so

randomly be exterminated. That we have lost whatever sense of safety and security that we thought we had about the world and that we are in an acute

state of grief at this moment, not just for physical death but for the death of the world that we have known.

AMANPOUR: It is really interesting that, because you have also talked about how — what’s happening is total disruption. Not just global

disruption but disruption of each individual’s life. So, given what you’ve just said, how are people coping? What do you tell them?

PEREL: So, look, one of the first things that people describe is how there is a complete amalgamation of all of our roles in the one place. I’m

sitting on the same chair the whole day in the same day and then, from that place, I am a therapist, I am a mother, I am a partner, I am a friend, I am

— you know, all the roles are bleeding into each other. All the weekend is same as the weekday. And there is this loss of demarcation and delineation.

Usually our roles are taking place in certain locals. We change for them. We go to different places for them. Now, it is all in one spot. And that

disruption is more than just a disruption of our routines and our sense of continuity, it’s a disruption of every ritual of our life. And so, the

first thing I say to people is, find ways to create borders. Don’t eat at the same time if you can or change the table, change the look. If you want

to have dinner with your partner and it’s just the two of you and can’t have a date, dress up, pretend you’re going out.

Children are our guides in this moment. They are able to continue to understand that freedom in confinement comes through our imagination. They

are talking to dragons. They are talking to kings. They are talking to imaginary people all the time. We need to access our imagination because

that’s the one place where we are currently not confined. We are maybe physically confined but we can still create an environment around us. So,

creating delineations is one thing that is going to go a long way. Finding some kind of structure within the chaos is suddenly being experienced. Not

trying to pretend that we are just working from home, as I heard you say, but we are working with home.

At the same time, as we’re working, the only borders that’s left for some of us is the mute button. You know, behind us is a whole cast of characters

sometimes and a whole life taking place that we are trying to ignore while we try to be professional here. We are working with home and that means

that we are working with the fears of others and we are working with the sleepless nights of others and we’re working with the stress levels of

others and we need to find ways to regulate all of that.

Put headphones on if you can on occasion. Listen to music that makes you feel good and brings joy to you. Take walks. Take walks alone on occasion.

Just move because we are so static in this moment that our entire sense of trauma and dread is contracting in our body and there is this undercurrent

of dread going on, which is not always named.

Sadness, fear, helplessness, despair, powerlessness, anger. Those are the emotions and it comes with gratitude and hope and courage. They are there,

too. And the more we name them, the less we react to them and the more we are able to actually articulate them and connect with the people around us.

This is the real-time for mass mutual reliance.

AMANPOUR: Mass mutual reliance, that’s really an interesting way to put it. I hadn’t heard that put that way. But can I just ask you because you

are also conducting your podcast, you know, “Where Should We Begin?” Couples under lockdown. And you still are dealing with relationships. And I

just want to play a little clip. It is obviously audio because the way you do it is you get them to agree to be published but also, obviously,

anonymously. This is a couple in Sicily and, you know, they’re sort of finding each other again. We’ll play a little bit of a clip and we’ll talk

about it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PEREL: What’s the one thing that you’ve been wanting to say to her?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: One thing that I wanted to say to you? I miss you. I miss you. I miss you. I know — I mean, I know I can’t just say I miss you

and then you come back suddenly. But I miss you and I want you. I want to be with you. You know, somewhere along the line, we were together and then

somewhere, something happened and we weren’t together anymore.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, you can hear that clearly, they had lost or drifted emotionally apart, although, we understand that they live in a small pretty

— you know, pretty small space in Sicily. Tell us about that and what you learned from that.

PEREL: Right. You know, so they are together for more than 15 years. He used to be the one who worked outside. She used to work outside. She was a

doula. She goes every day to the hospital. She delivers babies. She is afraid every day that she comes home that she may infect her three

children. And he has suddenly taken over that role. And they were living de facto in what we call an invisible divorce in their own home for quite a

few years.

And this sudden sense that they could lose one another, that they could no longer be that family, he realizes that he needs to find a way to reconnect

with her. And I get a chill when I hear him say it because he is actually able to — this is after talking around and around, you know. And suddenly,

he just says to her, I just miss you, you know. And I realize that a lot of the priorities are shifting in this moment and all the superfluous is being

thrown overboard and we touch to the essence and I want to show up for you. I want — I know you are going every day to the hospital. And while I’m

home, I want to do right by you and I want to find a way to raise these kids as best as I can.

He’s never done it and she been — she’s had a double shift basically for all those years. And they’re in this tiny little apartment in Sicily. And

what you see in the couples under lockdown, I have done three episodes right now in this new series. One is this couple where suddenly there is

that kind of, you know, can we — can this help us find each other again? And then there is another couple who were living apart for the last year-

and-a-half, they’re in Germany, and they were in a lockdown with each other because each one said to the other, you abandoned me. You didn’t follow me.

And somehow the virus decided for them, once Italy went into red zone, they got reunited. And for the first time, they are able to trespass beyond

their criticisms and to know that behind criticism there’s often is a wish, but it is much more vulnerable to talk about the wish than to blame the

other.

And then the third episode is a couple that has just filed divorce for the last two weeks before they went into quarantine. And so, he is not in

sheltering place. He feels like he is under house arrest of some sort. And they have to put that aside for a moment because they also have three

daughters and that’s what they need to do. It is like they need to find a way to manage the task because what they feel about each other in this

moment is irrelevant.

And so, what you see is the way this virus and this quarantine is intersecting with all the other normal developmental stages that

relationships go through from people who are single, to people who have gone back to being with their family, to people who suddenly find

themselves living with someone that they have just met twice to people who are separated but suddenly reunited for this occasion.

It’s this interplay between the regular stuff that happens in a couple with the added huge experience of being in this global crisis with prolonged

uncertainty when nobody really knows where this is going. And what that means is that, you know, a couple has to negotiate their different coping

styles. You may have one person who’s very much into self-reliance and self-control and another person who is much more fatalistic and has a much

better sense that things happen in life, you know. And these two people have to negotiate their coping responses in the face of something for which

nobody really has an answer. And all of that sits at the dinner table.

So, this is what the podcast is trying to capture in this moment. And it is very, very visceral because you’re literally in people’s home at this

moment. They’re no longer in my office. They’re literally, you know, in their tiny spaces. And so, you have a level of intimacy and an entry and

that has launched a conversation with thousands of people, you know, through a miniseries I’ve done on social, on YouTube, that is amazing

because people talk about mental health and — but not enough and they are busy talking constantly about physical health, this virus, have you been

exposed, you know, have you had it, have you — are you symptomatic, asymptomatic. But in fact, mental health is a part of our physical health

and the essential part of our mental health is our relational health.

And so, it is never named like this. And this relational health is what is going to help people when they — once they go back outside again. I mean,

these things are all interconnected. So, this is the contribution of one therapist to try to do something to bring meaning and clarity to this very

complicated experience.

AMANPOUR: Very complicated indeed. I just with to ask you, also, it’s kind of related. Basically, there are some, there’s some stories that suggest

that people, perhaps patients of yours, others, who have, you know, chronic depression and all sorts of other issues and are very unhappy, somehow are

managing in this — in a different, more resilient way than might be expected. They’re doing better at the moment.

PEREL: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: And I’m interested whether you have come across that and why.

PEREL: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And also, you are the child of holocaust survivors. And you know what it’s like or you know from your family what it is like to have

survived terrible, unspeakable trauma and you also spent time, obviously, being a therapist after 9/11 and, you know, near where you lived in New

York, et cetera. Can you talk about all those issues? How some people manage it better and that somehow counter intuitive?

PEREL: Yes, yes. It is a great question. You see, some of — this is true for my patients, this is true that we hear on our social channel. So, it’s

actually not just a few people here. If I have grown up with neglect and if I have grown up having to rely on myself and if I’ve grown up with chaos,

this is a moment where for which I’m actually quite prepared, you know.

And if I’ve grown up with those things and I’m still here, it is probably because there is a fair amount of resilience inside of me that knows how to

bounce back. So, our resources, our inner resources, our psychological strengths, often come from some of our most painful experiences. And in

this moment, it feels like my inner world matches the outside reality. This is the world. You want to know how I feel? This is it. This is how I live

all the time. You want to know what it’s like to live with danger, to live in neighborhood where there is no safety, to know that you could lose

somebody every day? Welcome to my world kind of thing.

And that suddenly turns into a strength for people because the reality on the outside matches the reality on the inside. It is not for all but it is

quite common, more common than we think. When it comes to my own experience, I would say, you know, my family they — my two parents lost

everybody, everybody. So, they were the sole survivors. And they decided that there was going to be a difference between not being dead and being

alive.

And I really understood that frame work for me. That what does it mean to actually experience pleasure in the midst of crisis, connection when

everything else is being destroyed, hope when you can experience despair? And that this becomes an antidote to the sense of loss and deadness.

And — but you live with the notion of dread. You know, this invisible current of dread that is pervading our society in this moment says, don’t

ever think that, you know, when you say I’m going to do this, you are in charge of it. There is a sense that any moment you can experience

disruption. That’s the legacy, if you want.

AMANPOUR: That’s the legacy.

But, also, I kind of hear you saying, in a different way — and I want to know…

PEREL: Yes.

AMANPOUR: … do people have permission to be joyful, to be happy, to think about something other than coronavirus?

(CROSSTALK)

PEREL: No, no, no. I cut you off, but continue. Sorry.

AMANPOUR: No. You continue. We have got a minute left. You tell me.

PEREL: Yes.

I think it’s such — because that’s part of the legacy, too. Yes, my father fell in love in the concentration camp. My mother sang songs. People wrote

poems. People wrote love stories. People held each other. People created community. People dreamt together. People had all kinds of premonitions,

dreams.

I think it’s extremely important to give ourselves the permission to experience pleasure in the midst of the crisis, to understand that, when

you are confined, your mind can actually go infinite and that your imagination is what is going to give you that sense of hope, and that it’s

not just that it’s a permission. It is a must.

It is something that keeps us alive and keeps us resilient. And it is in every story of resilience that we will learn from our families and from our

culture, is that ray of light that shines through the crack.

AMANPOUR: Well, you give it in spades. What a great conversation.

Thank you so much, Esther Perel.

PEREL: It’s a pleasure. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: The podcast, the newsletter, I hope everybody takes — takes a chance to get your wisdom. Thank you.

PEREL: Thank you so much.

AMANPOUR: Now, countless others across the world, our next guest has been personally affected by the coronavirus.

Peggy Flanagan is Minnesota’s lieutenant governor. And in March, her brother died because of COVID-19. Flanagan is the second Native American

woman elected to statewide executive office in the United States.

And she talks to our Michel Martin about how Native Americans, like the Hispanic and African-American communities, are being disproportionately hit

right now.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN: Lieutenant Governor, thank you for talking with us today. We’re so delighted to have you with us.

LT. GOV. PEGGY FLANAGAN (D-MN): Thanks so much for having me. I appreciate it.

MARTIN: I do want to offer the condolences of everyone here on the loss of your brother. And this comes just after you lost your father earlier this

year. So I do want to offer condolences.

FLANAGAN: Thank you. I appreciate that.

This has certainly been a difficult year for our family. My brother — my dad was hospitalized towards the end of last year. My brother drove up

north and stayed by his side until he walked on and until he was buried.

And then he went home to Tennessee, and just a few weeks latter started feeling sick, and went to the doctor, and was diagnosed with cancer,

received his first treatment, went home, and a few days later was admitted to the hospital due to difficulty breathing, a couple days later was

tested.

And it was confirmed that he had COVID. They needed to place him on a ventilator and put him in a medically induced coma. And he did not survive.

And so my family, we will have the opportunity to memorialize him, and his ashes will be spread next to my dad on the White Earth Reservation. And we

will have that opportunity in the future.

But, right now, my brother is a Marine. And he would have said, girl, get back to it. And that’s what we’re doing. And so many other families are

just trying to move through their grief right now.

MARTIN: I see. Well, again, condolences on that. And your story is that of so many others during this time.

So, let us speak about your public responsibilities. You are the lieutenant governor of Minnesota. You are the second Native woman to be elected to a

statewide office in the country.

So, there are 11 Native tribes in Minnesota. But I understand that your concern about tribal members really speaks to tribal members across the

country.

Are there specific concerns about tribal members that perhaps are distinct from those of everyone dealing with the current situation that you want to

highlight for us?

FLANAGAN: Sure.

Well, I think, you know, one of the most important things for people to know I think is that we still exist. There is an erasure that happens of

Native people.

And IllumiNative is a nonprofit organization that conducted a study where they found that 40 percent of Americans don’t realize that Native American

people still exist.

So, if you don’t even know that we’re still here, addressing and helping to find solutions to the issues that challenge our community, that becomes

even more difficult.

But, additionally, our health disparities are something that our community certainly deals with, underlying conditions such as heart disease,

diabetes, asthma, and then puts us even more at risk for contracting COVID and then developing complications from that.

MARTIN: Among Native Americans, actually, the incident of these conditions is far higher than in the general population.

Can you just share a little bit about that?

FLANAGAN: That’s correct.

So, we are at the top of many of the lists that you don’t want to be at the top of. And so, again, when it comes to issues around heart disease and

diabetes, any kind of complications, I think, you know, as we are tackling some of these things, too, we are also navigating through housing shortages

and access to food, all the things I think that some folks take for granted and a lot of our tribal communities are not often easily accessible.

And the biggest thing is that, you know, as we have been working with our tribes here in Minnesota, is just the acknowledgement that our tribes don’t

have a tax base. And so much of the revenue source for our tribes has happened through gaming.

And, you know, we certainly — the governor and I couldn’t issue an order asking casinos to close, but our tribal leaders made that decision on their

own and followed the state’s stay-at-home order. And that puts them in a really difficult position.

So, one of the things that we have also done is put together — as we were working on our response, in partnership with the tribes, we put together

tribal assistance fund that we were able to move through the legislature. It’s $11 million in that fund to then give individual grants to tribal

nations, so that they have some money while they’re waiting for the additional support to come in from the federal government, so that they can

get reimbursed by FEMA and other things.

MARTIN: The reality of it is that millions of tribal members get their health care through the Indian Health Service, which was set up in exchange

for access to, you know, tribal lands.

FLANAGAN: Right.

MARTIN: What is your understanding of the testing situation? We’re hearing from governors across the country that they’re competing with each other.

Is the Indian Health Service similarly having to compete with other entities for these things? What is the situation there?

FLANAGAN: First of all, I’m glad that you acknowledge just the — we were guaranteed two things, which was education and health care, in exchange for

all of this, the United States.

Indian Health Service has never been adequately funded and has never met the health care needs of Native people. And so now we have this crisis on

top of it. It’s simply only exacerbating, I think, some of those shortfalls.

But when it comes to testing, that’s correct, that we — that the Indian Health Service is also competing with the states to get the testing

equipment, the PPE. And we find ourselves in a situation where it sure would be helpful if the federal government did a better job coordinating

throughout the states and with Indian Health.

One of the challenges that we have had in Minnesota is, even when we receive these test kits as a state, the reagent that is needed for these

kits or additional swabs are not included. And so if you’re sending out a kit, you can’t actually use it unless it’s complete.

So we’re following up with the tribes in our state to find out if they have, in fact, received a full kit, so that they can begin testing. The

need has not been met when it comes to testing, I think, for states, but especially for our Native nations across the country.

MARTIN: The federal government has pledged — as part of the latest relief act, has pledged some millions of dollars to the tribal nations for the

same reason that this money is being sent to other groups and individuals.

Has any of that money been received yet, to your knowledge?

FLANAGAN: Some of it has.

I think the large amount of the $8 billion that was allocated by Congress, that money has not been distributed yet. And the issue there is that

Treasury has never directly granted or sent money to tribes before.

And so they’re trying to determine what the appropriate formula is for the disbursing of those funds. I’m worried about how that formula will be

developed. There are 573 Native nations within the borders of the United States of America. And for an entity that’s not done this yet, I think, you

know, we are all paying close attention to how they determine, as they’re going through consultation, how these funds will be disbursed.

But we are weeks and weeks into this crisis, and I worry about the ability to get that money out quickly and for folks to — for tribal leaders to be

able to meet that need.

So I know that many folks are paying close attention.

MARTIN: Now, you were telling that there are 11 tribal nations in Minnesota, that you and the governor were able to put together a package

for the tribal nations within the state, though.

What’s their situation, though? I mean, is your worst-case scenario coming true there?

FLANAGAN: So far, we are — you know, we do daily calls with tribal leaders, along with our congressional partners.

And, you know, I think that that’s been really important to make sure that we are communicating effectively with what the needs are, how to better

coordinate with local county health officials, that type of thing.

And we’re really — we were able to implement that because the governor and I have made sure that our relationships with tribal nations have been —

has been a real priority for our administration.

So, because of that relationship-building, we have been able to get to a better spot, I think, with coordination and response.

Now, we do know that, at the Red Lake Nation, for example, 600 of their tribal members are experiencing homelessness. And even — and that is a

real issue, as we’re thinking about how people can do social distancing, stay at home, limit exposure. And so we’re working with Red Lake on that

particular issue.

But our 11 Native nations — there’s four Dakota and seven Ojibwe nations in Minnesota. All have their unique situations. And we’re just trying to

communicate and get them the resources that they need in the short term or at least make those connections that to be able to respond to take care of

their communities.

But the one other thing that I would mention here, too, is that 50 percent of Native Americans don’t live on reservations. And so we have a pretty

significant urban population as well. And in Minnesota, you are 27 times more likely to be unsheltered if you are — than the white population if

you’re Native.

And so that is also an issue that we are dealing with here for our community members experiencing homelessness, which was already an issue, on

top of making sure that we have culturally appropriate responses through cities and county and through the state. So, that’s something that we are

working on now as well.

MARTIN: You’re saying a culturally appropriate response.

Tell me more what that looks like and how that might be different than for other groups.

FLANAGAN: So, for folks in Minnesota, the populations that we see experiencing homelessness at a disproportionate rate is the Native

community and the African-American community.

So, having culturally relevant support means that, oftentimes, folks in our community prefer to be in shelter together. But we’re also working to

support our shelter providers, as well as our street outreach folks.

And even just today, I got a text message from the pastor at All Nations Indian Church in South Minneapolis, who said that they are setting up

handwashing stations and a hygiene area, as well as connecting folks with food and medical care that’s available, that will be available three times

a week.

And so I think those are the kind of things where we need people to be creative right now and to meet folks where they are.

The other ability, the other hygiene stations or port-a-potties or handwashing stations were throughout our — the city of Minneapolis in a

place where they weren’t necessarily accessible to folks. And now it’s been an area where people will be able to utilize them, connect with each other,

and our hope is also get the support and medical care that they need that is delivered in an environment where people feel comfortable and is part of

the neighborhood.

MARTIN: Thirteen percent of Native American homes lack access to clean water, where the national average is less than 1 percent. That’s as a

national statistic.

You know, it’s been reported that and it’s been well-documented to this point that the death rate for African-Americans and Latinos has been

demonstrably higher than for other segments of the populations. We’ve seen this in New York. We’ve seen this in Detroit. We’ve seen this in New

Orleans. We’ve also seeing this in Washington, D.C.

Is the same thing true so far of Native Americans?

FLANAGAN: I think that you can see it happening in Arizona and in New Mexico.

And we are doing everything that we can here in the state, but I suspect that you can anticipate that the Native community will be

disproportionately impacted by this as well here in our state, which is, again, why we need those resources. We need the additional health care

capacity to be able to meet the need.

But let’s just be clear. I think — you know, I have heard some folks — and I’m sure you have, too — say that, somehow, the coronavirus or COVID-

19 is the great equalizer.

And I think nothing could be further from the truth. What this has done is simply laid bare the racial inequities, the socioeconomic inequities that

we have in our country, and knowing that, if you are a person of color, if you’re indigenous, if you’re an immigrant or refugee, that this virus will

impact you in a way that’s (AUDIO GAP) substantial.

MARTIN: A number of groups, activists and political leaders like yourself have been raising your voices in recent days to call attention to these

disparities.

But I want to ask you about the other side of it. Is there any part of you that is concerned that, when this — it becomes understood that the impacts

of this fall more heavily on some communities than others, particularly communities of color, that there will be less national urgency about it?

FLANAGAN: Well, yes, I certainly am concerned about that.

And I think this country has a long history of not feeling the urgency when it is black and brown people who are most impacted. And so, you know, all I

can do is work alongside the governor, but with other leaders.

I think a lot about Lieutenant Governor Garlin Gilchrist in Michigan or Lieutenant Governor Mandela Barnes in Wisconsin. We are all deeply

connected and lifting up these issues. And that is all we can do, is continue to really make sure that our people are seen and heard and valued.

MARTIN: Is there anything in particular that you are drawing inspiration from at this time to kind of guide you through this really unprecedented

moment, at least unprecedented in modern times?

FLANAGAN: While Native people, you know, are at the top of every list as far as health disparities go and rates of poverty and other things, I also

find great comfort in the fact that we are resilient.

And despite everything, everything that has been thrown our way, we are still here, and that I have a 7-year-old, little Anishinaabekwe, little

Native daughter, who knows who she is and knows where she comes from.

And that is what — sharing our ways with her and knowing that we are still here, that brings me strength every single day.

MARTIN: Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan, thank you so much for talking with us.

FLANAGAN: Thank you so much for having me. I appreciate it. Meegwetch.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And really important to highlight that issue.

Finally, from the West End and Broadway to his living room, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber’s world-famous news calls like “Phantom of the Opera” and

“Evita” were on stages around the world before the pandemic brought down the curtains.

Now they’re streaming online each Friday for free, providing lockdown entertainment.

Lloyd Webber has also started composing in isolation on social media, bringing his classics the life on his piano at home.

And that’s where he’s joining me from now.

Andrew Lloyd Webber, welcome to the program.

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: I want to start by asking how you’re doing with your sort of online performances now, particularly what we just talked about.

You have started The Shows Must Go On. And it’s not just for entertainment, although it is. What’s the bigger purpose, as you decided to put “Phantom”

and the others streaming?

ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER, COMPOSER: Well, one of the most important things is, we were able to — if people wish to donate to the Actors Fund, that is

really terrific.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

LLOYD WEBBER: I have been doing my bit as a producer through Broadway Cares.

But it’s a wonderful way of being able to help. But also, at this point, I mean, I have been very lucky in my career, and I think it’s a way of giving

back to the audiences who have been so good to me.

And maybe it also introduces people to the theater who may not have even thought of going to a theater. You never know.

AMANPOUR: And “Phantom,” of course, is the first one.

It is on now. And it obviously — he knows, the Phantom knows a little bit about being in lockdown, because he’s locked under the opera.

Tell us a little bit about it relates, how “Phantom” relates to this moment we are going through.

LLOYD WEBBER: Well, I don’t know that he specifically — other than the fact he wears a mask, I don’t think there is a — no, I think that the

“Phantom” really is an extraordinary love story.

And I think one has to think of it as that. But the production that you can see today is the 25th anniversary concert of it that was — it was shot in

London about five years ago now, six years ago. And it was done in the Albert Hall. It’s not the theater, but it is a very, very fine production.

And I think we are all very pleased with it.

AMANPOUR: And, look, just to give it some more resonance, some of the song lyrics are appropriate.

There’s this one, wishing you were somehow here again, wishing you were somehow near, a little bit of what people are going through in isolation.

You just heard Esther Perel, the relationship guru, talking about how difficult it is.

But you have also, yourself, I think you have got a musical that I think has been either stopped before it started or closed very quickly,

“Cinderella.”

LLOYD WEBBER: Oh, yes. Well, it hasn’t closed, no. It has been stopped in its tracks. We were supposed to be doing a workshop for the last three

weeks, not been able to do it, although, thanks to Zoom, of course, and things, we have able to continue with all the writing.

And we have been able to make sure that we finished it. Of course, quite when we’re going to be able to put it on now is an open question, because

the big question all of us are asking is, when is it going to be possible to go back to the theater again? When are the theaters going to be open?

And then, of course, when the theaters are open, are audiences going to feel safe to go? I think we have got a moment now, I think particularly on

Broadway, where I think it’s very, very important that everybody pulls together. I don’t mean just, you know, the writers and the actors and

everything, but I think everybody, backstage, stage hands, you know, and indeed the theater owners, have got to pull together to make it possible

for the public to go.

I don’t think there’s going to be the money around to spend on theater tickets in the way perhaps there has been. And I feel very strongly that we

have got to try and make theater as accessible and as safe as possible for people to go to.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

And, of course, I mean, you have just said you feel very privileged. You have been able to have this career. And you’re giving back. And some of

what you’re trying to hopefully get donated is to the Actors Fund.

Just talk to me a little bit about the everyday actors, many of the people who work in theater, even if they’re not on stage, just to make it happen,

what they must be going through right now in terms of loss of revenue, loss of job and uncertainty.

What are you hearing?

LLOYD WEBBER: Well, it’s practice. It’s so much hearing. It’s seeing. It is just very, very difficult for absolutely everybody.

You know, I, as a theater owner in London, what do we do? We have not made any of our staff redundant. But we can’t go on forever, because we’re a —

in the end — I mean, I run my theaters not-for-profit.

And it is very difficult for all of us. I have chosen in Britain to support the Musicians Benevolent Fund, because our musicians here are freelance, in

a way perhaps that they aren’t to the same extent in America. And it’s a very big issue for the musicians.

But, of course, the big issue that you have, which, of course, we don’t have here, is, is that we do have free health care. And my biggest concern

for the actors and for everybody in New York and all over America in the — where our shows has been is the health care issue that I feel most, most,

most concerned and worried about.

AMANPOUR: You know, you’re absolutely right. And we had the head of the IMF on at the beginning of the program, saying that, you know, some — many

economies may have to rethink what they prioritize, like health, education, and all those other important issues.

You — I know that you have a foundation. You provide free music for many people who may not be able to and scholarships and this. Just quickly,

before we end, tell us what you have found and what you think is the value added of music to people, whether when they can come to theater or when

they can’t and when they’re closed off in a moment of such deep anxiety.

LLOYD WEBBER: Well, I think, as I ponder it, I think we all know, over the years, really, that music empowers

And that’s why I’m particularly, particularly keen and passionate about music in education, because one has seen in schools, where perhaps, in

difficult areas or backgrounds where they have social problems, music has been the common denominator force for the good.

And the thing about music is, is that, you know, it transcends all languages. I can give you an example of one school where I thought it was

46 different languages, but, in fact, it was 60 different languages that were spoken there. And music is the common denominator.

And I feel passionately that music should be the right of every child everywhere. And I think that, at this moment, music is a great leveler.

AMANPOUR: Well, we have seen so much fantastic music online during this. And I just wondered whether you would be so good to play us out as we say

goodbye?

LLOYD WEBBER: I will do.

What I’ll do is play a little bit of “Think of Me,” because, on Sunday, I have been doing these challenges. “Think of Me” ends with a cadenza, where

the singer sings something which is really very difficult.

I have asked people this coming Sunday to make up their own cadenza. And I tell you what. If we get some good really ones, we will put them into

“Phantom of the Opera” when we reopen in London and Broadway.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: OK.

LLOYD WEBBER: So, a little bit of “Think of Me.” Here we go.