Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

In a world paralyzed by coronavirus, clearer skies and animals roaming free, we celebrate Earth Day at 50 with legendary broadcaster and

pioneering naturalist, Sir David Attenborough.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

GOV. JAY INSLEE (D-WA): We have one chance to defeat climate change, and it is right now.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The presidential candidate who put the climate front and center of his campaign. Washington governor, Jay Inslee, joins me as he tackles

these twin emergencies.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MADELEINE ALBRIGHT, FORMER U.S. SECRETARY OF STATE: Trying to divide society rather than trying to find common answers is one of the steps

towards authoritarianism.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Nationalism on the rise as the pandemic takes over. Former U.S. secretary of state, Madeleine Albright, on long-term implications for the

world order.

And finally, reimagining our world after COVID.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour working from home in London.

Coronavirus continues to ravage globe, endangering our health and our economies. But another crisis has been threatening our planet long before

COVID-19 appeared and that is the climate emergency. And today is Earth Day.

While it usually brings people around the world together, on its 50th anniversary, today, lockdown means that it is being celebrated in silence,

but its message is more important than ever. With economies frozen, pollution is plummeting, our skies and waterways are clearer and our air is

cleaner.

The World Meteorological Organization says the pandemic will reduce carbon emissions by 6 percent this year. It’s the sharpest drop since World War

II. But even that is not enough to reverse the dangerous effect of carbon emissions.

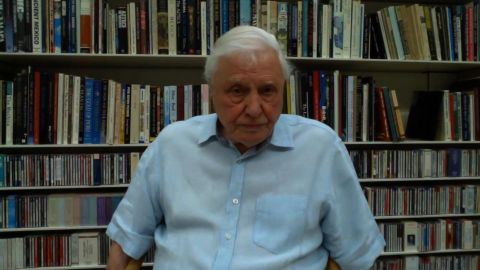

So, how do we turn this opportunity into a lasting change? Of course, there’s no one better to talk about the wonders of our planet than the

world-renowned naturalist and leading conservationist, Sir David Attenborough, who is joining us live via Skype from home.

Welcome to the program, Sir David.

And I just wonder what you think of kind of being inside unable to go outside and celebrate Earth Day, and all the changes that our planet’s

seen, certainly since you were born.

DAVID ATTENBOROUGH, BROADCASTER AND NATURALIST: Yes, indeed. I mean, the world has been transformed. And I’ve been extraordinarily lucky and that

I’ve been filming (INAUDIBLE) since 1950s. And so, I’ve got enough video documentation of how it looked to me when I was in my early 30s and it was

a different world altogether.

I could see things that nobody else had filmed before, certainly. I could travel into places where hardly anybody had ever been before. It was a

marvelous, pristine world and it was rich. And yet, of course, it was still being depreciated. Had I been there 50 years before that, I would have seen

even a greater thing. But now what I realize, of course, looking back now, is how the world has become poisoned and depleted and is wrecked really

from many points of view and other dangers on the horizon.

AMANPOUR: Let me ask you before I go back because you’re right. You know, in your life span, I mean, you’re 93 years old. That’s a well-known fact.

I’m not being discrete. And, as you say, you have seen the massive transformations. But I led into this and surely you, obviously, have been

on top of it, as well, by talking about the incredible blue skies, the lack of carbon and pollution in our air, the cleaner waters right now, we have

seen animals roaming around as if it was still a natural world in highways and streets of urban centers. Do you — I mean, do you think, wow, look at

what could happen if we put our mind to it?

ATTENBOROUGH: Yes, very much so and this glorious weather. Of course, I’m locked in, as we say. So, I don’t get out even though I’m close to one of

the loveliest parts in Great London, in Richmond Park, I can’t go there. I’m supposed to stay at home, which is what I’m doing.

But the skies are so blue. The bird song is so loud and I can hear it over because there are no airplanes. I mean, I live quite close to London

airport. And normally I wouldn’t be able to talk for longer than 90 seconds or so before a drone of an airplane came by. Now, it’s an event to see an

airplane in the sky and I hear the bird song.

So, it’s — and — but also, the air is purer. And when you hear reports of fish coming back into Venice canals and so on, you realize the world is

actually changing. And being that changed, being forced upon us, the question is, are we going to be strong enough to keep these changes and do

what’s needed to retain these improvements in the years to come when we have got over this particular hump and problem.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And we said that pollution, according to the Meteorological Organization, is going to drop by carbon emissions 6 percent this year,

which is a big, big drop. But I wonder, look, you have been a broadcaster most — all your life and you have sent out the message of loving this

planet, caring for the animals, caring for the natural forests and all the natural world, and I wonder whether you think, because it’s been suggested

that a simple message, stay home, stay safe during this coronavirus has worked. People are doing that. They’re obeying it.

Do naturalist, climate activists, people who care need to come up with a simple message that will be equally powerful once we get out of this for

the climate?

ATTENBOROUGH: Yes, we do. But you can’t have a more powerful message than we have now because you didn’t actually make mention the second half of it.

Of course, the government is saying stay in. Because if you don’t there is a risk of a deadly disease. That’s a pretty big threat.

And when the government says or whoever it is says that threat has disappeared, will we have the strength of the mind then to say, OK, well,

we won’t use the highways as much as we did? We will stay at home if we can. I think that one of the changes that may well happen in the coming

years is that actually people have discovered that you can work in this day and age with the various devices. You can work very well from home and

there is no need to have to endure that dreadful journey packed into like sardines in tins going into the middle of the city.

May be there will be a shift in the way we work. Now, if there is, that’s happened because people prefer it that way. But do they — when they prefer

to say, oh, well, we don’t — we’ll give up the overseas holidays. We don’t need to travel as much as we want because we want to reduce the amount of

noise in the atmosphere and in the skies or indeed, the carbon dioxide that we are wasting on traffic, on transport that we don’t need. That’s the

question. Will we do it? Do we care enough to do things that we don’t enjoy as obvious improvements?

AMANPOUR: So, you know, you say will we care enough? And that we’re facing a health crisis right now. That’s true. But of course, the climate crisis

is an existential crisis for our species, as you have said and many others have said. And I found it really interesting that today on Earth Day, Ipsos

MORI, which is a very, very reputable poll says two-thirds of the British people believe that climate change is as serious as coronavirus and the

majority want climate prioritized in the economic recovery.

And I know that you have — you know, you have moved from being just an observer and a lover of nature to somebody who uses your incredible voice

and platform more as an activist and telling people and warning them about what’s ahead. I wonder what you think of the younger generation, people who

are saying this about what should happen in the future.

ATTENBOROUGH: The heartening thing about what you just described is that young people who are going to inherit this earth, young people have made it

absolutely clear how vigorously and vehemently they feel about what is happening to the planet. And it is that, as in any democratic society, our

leaders and our politicians to take that seriously.

Before, 20 years ago, I don’t think the politicians did take it seriously. I thought they thought, oh, well, you know, it’s 20, 30, 40 years ahead and

we’ve got urgent things to do tomorrow and next week. They didn’t really take it seriously. But young people now are insisting that they take it

seriously, and that has been the major change, I think, in public mood over the past few months.

AMANPOUR: What do you make of Greta Thunberg? I know that you have talked to her, you have talked about her. And she is quite incredible in terms of

moving the dial.

ATTENBOROUGH: She is incredibly well informed. She’s also extremely modest. I mean, she says over and over again, I’m not saying anything. It

is science that’s saying these things. And if we believe in science, if we believe in knowledge, if we believe in wisdom, we must take notice of what

they are saying. It is not me. I’m in my teens. I’m young. But I do know that I may not know the facts of ecological sophistications, but what I do

know is that the world is going to be for me to live in for the next 50 years or so. And that’s pretty powerful.

AMANPOUR: Let me just read a couple of stats, because you started by saying the world has changed a huge amount since you were born, since you

were a young man. You were young in the 1930s when 66 percent of the world was wilderness and carbon dioxide levels of 310 parts per million. When you

started your first blue planet in the late ’90s, wilderness was down to 47 percent. And now, it is 25 percent, barely 25 percent of our world.

So, in your lifetime, it’s gone from 66 percent wilderness to 25 percent. And it’s gone from, I don’t know, at that time, it must have been about 2

billion on the planet. Now, it’s, you know, 7-plus billion on the planet. And a lot of this disease, many are saying, representable doctors are

saying, is partly because of overpopulation and over farming of these animals. What do you say to that?

ATTENBOROUGH: Well, it is not so much overpopulation as dense population. The density of the population. And epidemics are not new. Though, you know,

there was the black death a few centuries ago. There was the great plague in the 17th century. In which people were dying in huge numbers in the

convocations, in the big — well, I chose the word convocations, where there were dense cities. Certainly, London was a city in which was — there

were over density of population was huge and people were dying in great numbers. So, it’s not new.

And anybody who knows anything about keeping animals, farmers know perfectly well and anybody else who looks after living creatures, if you

keep them in great densities, the transmission of disease once it starts goes like wildfire and very difficult to control. Well, we are living in

huge densities. You know, homo sapiens has increased in numbers, as you’ve just said, over three times as many as when I was making my first programs.

It’s extraordinary.

So, it is not surprising that, in fact, we are getting the come-up pans (ph) from that point of view. But it’s not nature, it’s not nature having

revenge or anything like that. It is a basic fact of life that if you have huge densities of population, you will get diseases spread very swiftly in

them.

AMANPOUR: One of the — well, your latest film “A Life on Our Planet” was meant to have premiered last week ahead of Earth Day. Because of this

crisis, that has been delayed. What were you saying in that documentary? What were you saying about your experience and how you’ve, you know,

watched these developments and what legacy you want to leave?

ATTENBOROUGH: The filmmakers who suggested it pointed out to me that actually I’ve had a film record, I’ve been making films in the wild since

the 1950s, early 1950s. And before that, I have plenty of memories of running in the English countryside and looking at birds and collecting

fossils and being aware of the natural world. And so, I had seen that change.

But I dare say I wouldn’t recognize that change and we’re not very good at recognizing slow changes unless it had, in fact, been recorded and so. But

it’s when I now look at those films of lakes covered in wild fowl of various sorts and other, I suddenly realize, yes, that’s gone. That’s

changed. It’s that record which has made it so vivid to me as to what has been going on in my lifetime.

AMANPOUR: And now, while you’re in lockdown, you are also taking part in a BBC experiment whereby a lot of you are teaching young kids and you have

decided to teach geography for a while. What are you telling the kids? Why have you decided to jump into this fray? What’s it like being an online

teacher?

ATTENBOROUGH: Well, I can’t pretend that we’re making special lessons in that sense. But on this very afternoon, I’ve been recording an introduction

in sound (ph) to some of the films which I have made in the past and which will be brought out and be shown again because they have a very precise

educational message in them.

And so, I’m introducing them saying look at this. Look at the oceans. Let’s look at the ocean. They covered two-thirds of the world. And they have

creatures in them, they vary from this, that and the other. And let me show you what goes on and the way it’s all interconnected. And then we will show

sequences from planet or indeed, other series, which I have done in the past.

And we are — those are being edited by people who are specialists in learning by television in order to convey the messages that will be

helpful. My commentary won’t be changed but only my introductions will be added.

AMANPOUR: I just want to end by saying you do have some solutions and you have talked about these, make large no-fishing zones to give stocks a

chance to recover. Reduce land farming by half, humanity must eat less meat, you believe, and phase out fossil fuels. Of course, that’s a huge

endeavor that — you know, with — the world is trying to get to.

But I also just wonder, you’re 93. You say you can’t go out even to the park, which is right outside your door. What is it like experiencing this

at this point?

ATTENBOROUGH: Well, I’m embarrassingly lucky. I have a reasonably large (INAUDIBLE). And I walk — but I walk around it more in the past three

weeks, I suppose, or a month than I have for years. Because I now walked closely different plants of which I’m particularly fond the way in which

they are developing. As that (INAUDIBLE) — as I have developed that great spike yet.

So, every day I go around hoping that I’m going to see that particular change. And of course, the weather’s been so lovely, the birds have been so

beautiful that it’s such a consolation. It’s interesting, isn’t it, that doctors and medical profession know very well now that an appreciation of

the natural world and contact with the natural world actually brings huge benefits, huge benefits in our pieces of mind and our peace of mind.

AMANPOUR: Right.

ATTENBOROUGH: Huge benefits in terms of us — of our happiness and our relationship with the natural world.

AMANPOUR: Well, boy, you have brought that to such a massive global audience and we are all happy that at your films. Thank you so much, Sir

David Attenborough, for joining us on Earth Day at 50.

And up next, we’ll talk to Governor Jay Inslee of Washington State about how he’s managing these twin emergencies, coronavirus and the climate. But

first, here’s Correspondent Paula Newton with a closer look at the animal kingdom and that natural world that Sir David has just talked about. They

are loving our lockdown.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PAULA NEWTON: Horns. Engines. Train whistles. People out and about. The background sounds of everyday life gone quiet. With

coronavirus shelter in place orders around the globe, it is turning the tables on human norms. Animals are filling up the empty spaces. From wild

deer trapesing through the streets of Japan to lions lounging across the streets usually traversed by cars in a Kuru (ph) national park, to herds of

goats in Wales helping themselves to neighborhood bushes and flower beds. The animal kingdom is for now reclaiming spaces normally occupied by

people.

And no, it’s not your imagination. Birds do sound louder. A phenomenon that some experts say comes in part from birds being less stressed by human

sounds. Causing them to congregate in larger numbers and more easily communicate with each other.

MAHER OSTA, SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATURE IN LEBANON (through translator): The birds are more relaxed. They are not trying to get away

from cars, from the crowds of people, even the heart of the city itself.

NEWTON: And in Thailand, researchers say there’s a baby boom as sea turtle nests are at a 20-year high thanks to the absence of people walking in the

sand where these endangered species lay their eggs.

But some animals are noticing the void left by their human counterparts. Monkeys like these used to tourists feeding them on a daily basis swarm

over a little bit of food left behind. And for the great apes and giraffes and other wildlife used to putting on a daily show in their zoological

homes, some workers say they’re now playing the part of tourist, alleviate signs of sadness they notice from the animals who still move like clockwork

each day to the very spot they used to interact with spectators who are no longer coming the parks.

But as spring blooms in much of the Northern Hemisphere, the quieter, gentler atmosphere may be beneficial if only far short time. Bears are

waking from hibernation, a bit more free to explore. Newborn ducklings, baby elephants and the like emerging into the world at a time when the

earth is vibrating just a little bit less and turning just a little more slowly.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: It’s really a beautiful reminder of what could be.

And we turn now to the United States which together with China, the world’s biggest polluters. Let’s not forget that Earth Day began in the United

States 50 years ago after a major oil spill off California. Back then, it was not riven by partisan politics like it is today. Indeed, Republican,

President Nixon, created the EPA, the Environmental Protection Agency.

50 years later, Democrat Jay Inslee ran for president with climate at the heart of his campaign. And as the current governor of Washington State, he

saw the first cases of coronavirus appear in America. And the governor is joining me right now from Olympia in Washington.

Governor Inslee, welcome to the program.

I just want to ask you on — you know, on this climate day, I want to start with the climate because you were really out there running for president on

a climate platform. Just your observations on this 50th anniversary, how far we have come, how far we have to go.

GOV. JAY INSLEE (D-WA): Well, listen, I know these are hard times but there is — big things to celebrate today. We can celebrate that not even

COVID-19 can steal the voice of David Attenborough. He is an international treasure. And I’m so delighted to know, I thought I was hallucinating that

the birds are so much louder now. That’s now been confirmed by David Attenborough. It’s actually good news.

We have good new that we continue to have tremendous achievements in building a clean energy economy. And I think this Earth Day is a day to

celebrate the potential of restarting our international economy by building a clean energy economy that can put millions of people to work, cause

massive reinvestment, which our economy is going to need so desperately as we come out of this pandemic. At the same time, we’re building a new

economy that cannot destroy the planet.

And I believe we’re going to be able to do that. I believe the United States is going to regain its leadership position in the international

community. We’ve got a great candidate, Joe Biden, to do that. So, I think there’s a lot to celebrate. And I want to give a shoutout to the guy who

started this, who is a Washingtonian, his name is Denis Hayes, a good friend of mine with Senator Gaylord Nelson. And he is still around in a

vigorous advocate for these measures. And we are making progress in our state where we have a plan to decarbonize our economy. And I’m very proud

of the work we are doing.

AMANPOUR: Let me just ask you, do you remember where you were April 22, 1970 when the first Earth Day happened?

INSLEE: I was on my favorite planet somewhere on earth, and that’s as much as I remember to be honest with you. But I was fairly early to this

endeavor. I got started in this effort in 1972 when I studied environmental issues, and went to Stockholm, Sweden and I studied — we did a research

project comparing the energy policies of Stockholm to Seattle, Washington, and went to the very first United Nations conference on the environment in

Stockholm in 1972. And so, I’ve been at this for a long time.

And the lessons I learned way, way back 49 years ago were still the ones we’re working on today, which is you can embrace new technologies and you

can reduce the impact on the environment while still maintaining a really high quality of life. Those lessons have been good for 49 years. And every

year, we improve our ability to do that. We just need the will to do that. And I can tell you from the United States, I think that is growing

dramatically on this 50th anniversary.

It certainly is in my state where we have passed the best energy efficiency laws in the United States and the most aggressive decarbonization laws for

energy electrical grid and some really good policies on transportation. So, what’s happening in my state, I’m very happy about. We got more work to do.

So, I look at today with all of our challenges that it is a day for celebration.

AMANPOUR: So, let me just quickly ask you because it is also political now. In the introduction, I mentioned that there’s a hyper partisan issue

and that the first EPA creator was a Republican president. And in the last, you know, decades, the world, you all did manage to cure the ozone layer,

cure the hole in the ozone layer by a very simple sustained appeal to get rid of CFCs. If you could do it then, what is the problem now?

INSLEE: Well, it is a great conundrum and a bit of a mystery. You know, the first head of the Environmental Protection Agency was a Washingtonian,

Bill Ruckelshaus, who worked for Richard Nixon in that regard.

So, we have had good Republican leadership in decades gone by. And, unfortunately, it has disappeared. It’s a great void. And we’re looking for

the day again when this becomes a bipartisan effort. But while we are waiting, and we cannot wait for the evolutionary process to evolve, the

Republican Party, to produce some leaders, we have to act.

And frankly, that means by electing people who will act in the presidential race here in the United States, this next year, I think we will have a

greatest contrast of someone who has ignored science, who has been deceiving or trying to deceive Americans about the science of climate

change, and has been in an abysmal failure trying the protect the health of Americans.

But we have another candidate who has introduced the first bill on climate change in the United States Senate. It was either 1986 or 1988, and most

importantly, was very successful in helping rebuild our economy after the last collapse in the Recovery Act and Joe Biden led the effort that built

$90 billion worth of infrastructure and created 3.3 million jobs in America. And I think we are going to have a really great race and I believe

the person who is an optimist is going to win that, and that is when American leadership will begin to be restored.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, you have endorsed Joe Biden clearly enough. For all the reasons that you have just laid out and more, probably.

INSLEE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: But what I want to ask you this. Because, clearly, the United States, like the rest of the world, is in a deep economic hole right now

because of coronavirus, the halting of the global economy and, as always, the poorest and the most vulnerable are going to be the biggest losers.

At the moment, while all these, you know, disaster relief bills, for want of a better word, go through Congress we also see the White House and the

president trying to bail out fossil fuel companies and all the rest of it. And also, conduct a major undercover of coronavirus assault on EPA

regulations and clean air and water and mercury and all those things are happening right now.

How is that going to be reversed? And do you think you can get what the U.N. secretary-general’s calling for, proper resources, you know, into the

recovery bills for the climate?

INSLEE: Well, we should be as ambitious and insistent with the United States Congress as possible. And the reason is, is that this is a twofer.

Any investment in clean energy technology to give Americans a shot including those who are most economically challenged at a good job building

good technology to help provide better health, any dollar that we invest in this is both a dollar to help Americans’ health and a dollar to give a

boost to the economy.

And I will tell you, I think that the right metaphor to think about on what we have to do to restore, really, the international economy and, at least,

the American economy is the thought of what we did to get out of the depression. And I think that we have to think grandly in that scheme. And

frankly, the only thing that got America out of the depression are the investments associated with defeating fascism. And that investment got us

out of the great depression.

And so that level, that scale of ambition, I believe, is necessary and we have — clean energy is not the only thing in America. We need a new

transportation infrastructure. We need the utilities. Our sewers and pipes are eroding like crazy. So, clean energy is one of the things we do but is

a thing that will have the most long-lasting impact and it has the greatest job creating opportunity.

AMANPOUR: Right.

INSLEE: A dollar in clean energy creates more jobs than any other sector of our economy. So, we need to look at this through a lens of long-term

health and short-term economic gain. This is a no-brainer. I hope Congress will do it now. But if the president is an unmovable object, he will have

to be removed from office an get on with the people’s business in January.

AMANPOUR: I mean, it is extraordinary, because it is a huge job provider in the United States.

INSLEE: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And you think that that is what’s required. I’m talking about the environment and those kinds of green economies.

But I want to ask you this. The attorney general, the attorney general, Barr, William Barr, has said that the Justice Department is considering

legal action against governors who are too slow to reopen their states. And he’s prepared to act against state and local officials.

Could you find yourself in a bind? We see these protests, even in Washington state, against the lockdown. We know that you last night made a

speech in which you describe turning the dial, not flipping a switch, in terms of getting the economy back together.

What do you make of this threat from the Justice Department?

INSLEE: It’s what I make a lot — of a lot of what comes out of that administration, which is a bunch of baloney that won’t take place.

Look, we have seen Donald Trump in court, at last check, I think 26 times. So, we have been involved in litigation with him 26 times, and we have beat

him 26 times.

So, I am confident that the under the American system of democracy, we reserve the rights to the states that are not abrogated to Congress. This

is a right that is reserved. And Republicans and Democrats, governors, both are doing some good work trying to save the health of their citizens.

It is unfortunate that this administration has chosen, as they have on climate change, to ignore science, to ignore epidemiology, to ignore his

own physicians who had told the president that we should not be releasing these restrictions right now, because we’re not ready to do so.

And I have always wondered where we will reach the bottom with this president. But we’re getting close to it when, after his own order said

that the conditions do not exist to go back to normal yet, his own guidelines, the next day, he went out and tried to get people to ignore the

laws of our states.

So I think Republicans and Democrat governors are united that this is a decision that people who put on these orders are the only ones who can take

them off. And they’re going to do it making some really hard judgments. And these are hard judgments.

Look, these are hard times. People are suffering economically. We get that. But we’re going to make decisions that are good for our people. And I think

Mr. Barr can — he can just take care of some other problems.

AMANPOUR: I see you’re being diplomatic there.

Let me — let me ask you another very serious issue.

(CROSSTALK)

INSLEE: … very diplomatic.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: Yes, yes, you were. You were. You hold — you held it in.

INSLEE: Thank you.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: But here’s the thing. The president has also pitted the federal government against the states. And there’s this whole hullabaloo about

who’s responsible for what.

And — but he’s just had a meeting with Governor Andrew Cuomo, in which they seem to resolve something about federal and state responsibilities,

different responsibilities for the testing situation.

But, also, he said that, in fact, there should be more stimulus for the states. And he also said that, actually, that’s something that both

Republicans and Democrats support.

But this is what McConnell said, who’s the leader of the Senate, that there would be no bailouts for states. Let me just play this for you.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP)

SEN. MITCH MCCONNELL (R-KY): What they wanted to strike the most, I refused to go along with, and the White House backed me up. And that was,

we’re not yet ready to just send a blank check down to states and local governments to spend any way they choose to.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So is there a left hand and a right hand there that’s not quite clear about what’s happening, because — or do you believe McConnell or do

you believe the president when he says that there needs to be more stimulus, more help for the states?

INSLEE: Well, I have seen a remarkable bipartisan approach from the governors, Republicans and Democrats, all whose economies have been

hammered, and all those people desperately need additional services from their states.

And Republicans and Democrat governors both have been very adamant with the president — and I have been on multiple calls with him — that our states

are not going to be able to provide the services that our people need in this emergency unless they get some emergency help from the U.S. Congress.

So this is not a moment where ideology should prevent us from getting health care to our people or housing to our people or foodstuffs to our

people. These are basic necessities that are jeopardized by Mitch McConnell and the president’s apparent position this.

I don’t understand this, because even the Republican governors get this. I think this is the difference between people who really have responsibility

for the health of their citizens — and those are governors — and Republican senators, who want to make this some kind of ideological

argument.

This is not a moment for ideology about the proper role of government. This is an argument about whether people are going to have food to eat in our

states. So, I’m hopeful that the Congress will act on this on a bipartisan basis.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you, in the last minute or so that we have left, about the next big challenge? And that is the election in November in terms of

the procedures.

You, Washington state, is one of only five, I believe, that does all your elections by mail-in, by ballot. Do you think — I mean, it’s clearly a

model. It’s clearly the kind of reform that may need to be enacted now to protect the integrity or the possibility of an election in November.

Are you concerned? Do you see any problems with Republicans who have said that — have shown themselves to be reluctant for this kind of reform? What

do you think needs to happen now?

INSLEE: Well, I would very much encourage people across the country to look at our experience, to look at Oregon’s experience with all mail-in

ballot. It has been fantastic. It is easy, it is safe. And safety is very important now, when people have to vote in some sense, you have to risk

your health to go vote and stand in a line next to people sometimes for hours.

This system has had virtually no fraud, no glitches. It has been very efficient, so efficient, I actually paid for stamps to get free postage out

of my emergency account last year, because it’s so popular. People really like it.

And when you do this, you get more people who do vote, because it’s so easy to vote. So I highly recommend the experience.

Now, what we are up against, unfortunately — and it’s sad to say this, but we have a lot of people in one of our parties that don’t like more people

voting. I don’t think that’s an American approach, or English approach, for that matter. In a democracy, we ought to make it so that people can vote.

They don’t like that, because, when more people vote, sometimes, their candidates don’t win. Well, that’s something you got to get over. And so

I’m really hopeful that this can expand. It should be the law of the land. I believe Congress should act itself to create more federal standards on

voting, so we can’t have pockets where local officials try to suppress the vote of certain groups.

And we know that’s going on in our country.

AMANPOUR: OK.

INSLEE: And that needs to end.

AMANPOUR: Well, we will be certainly watching that.

Governor Jay Inslee, thank you so much.

INSLEE: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: We wish your state the best with this corona epidemic. And we wish you the best with the climate as well. Thank you so much.

INSLEE: Thank you. Wash your hands.

AMANPOUR: Now, our next guest…

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: I always do.

Our next guest once called the United States the indispensable nation when it comes to leading global action. Yet President Trump has shown no

interest in this role.

As the first female U.S. secretary of state, Madeleine Albright spent her career using the power of American diplomacy to solve international crises.

Our Walter Isaacson spoke to her about the urgent need for return to that model, which she lays out in her new book, “Hell and Other Destinations: A

21st-Century Memoir.”

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Secretary Albright, thank you so much for joining us.

MADELEINE ALBRIGHT, FORMER U.S. SECRETARY OF STATE: It’s great to be with you, Walter. Really looking forward to this.

ISAACSON: Thank you.

This coronavirus has caused an immune reaction, you could call it, around the world. And that immune reaction is to retreat towards tribalism, to

retreat towards nationalism. Why is that happening?

ALBRIGHT: One of the things that I have talked about is that there have been two mega-trends and their downsides.

So, one mega-trend has been globalization, there’s no question. And many of us have benefited from that. The downside of it is, is that it’s faceless.

And people are looking for their identities.

And there’s nothing wrong with really wanting to know who you are and where you come from and all that, but if my identity hates your identity, then it

leads to hypernationalism, and that is very, very dangerous.

So we have seen more of that recently, due to the facelessness, but now exacerbated also by the fact that we are theoretically trying to fight a

common enemy, whereas we are behaving as if viruses don’t — you know, viruses don’t understand borders. They are all over the place.

ISAACSON: Even before this crisis, we were seeing the rise of authoritarian leadership from Turkey, maybe all the way around the globe.

Why did that happen? And who stands out for you in that regard?

ALBRIGHT: Well, I think that it happened because we have not handled the role of technology in our society very well.

And you and I, Walter, have spent so much time in the past talking about what happened to the social contract, whether people that are part of a

country where the government is supposed to provide them with a certain amount of living standards, the government doesn’t live up to its

responsibilities, and the people don’t live up to their responsibilities.

And so I think we have been in an era where technology was misunderstood, where societies are divided by where they get their news. And so then you

find leaders who are — take advantage of it, who are opportunists, and then create their societies according to that.

Viktor Orban is one of them. Erdogan in Turkey is another, Duterte in the Philippines. And we have seen it in a variety of places. And I think that

trying to divide society, rather than try to find common answers, is one of the steps towards authoritarianism.

ISAACSON: What do you feel about China’s response to the virus, whether they were transparent and open enough?

ALBRIGHT: I do think, Walter, that the Chinese are going to have to answer for a lot of issues to do with where this all came from and when they said

what.

But what I’m very concerned about now is, while we have to look into that, we really have to figure out how we move in the future and what the plans

are. And given that it is true that we’re interconnected, we are actually very dependent on the Chinese supply chains and how we operate together.

And I was recently asked, what would happen if the Chinese came up first with a vaccine? Would we say we wouldn’t deal with it because it was

Chinese? And so I think we have to figure out how they ultimately take responsibility for this, but, at the moment, I think we need to look for

paths where we can cooperate to resolve this crisis.

ISAACSON: How did you feel about America and the Trump administration pulling out funding for the WHO?

ALBRIGHT: Well, I think it is so counterproductive. We can’t do anything if we’re not at the table.

And by blaming the WHO and saying that we’re not going to contribute, we are contributing to one of the mechanisms for dealing with the issue of the

virus. And so it is basically counterproductive in every single way, lowers our influence, and just makes it clearer that the U.S. is AWOL in a number

of different ways of trying to resolve what are the really big problems of the 21st century.

ISAACSON: Is the criticism of the WHO, which is that they were soft on China in the very beginning, valid? And do you think some of the steps that

Trump has taken might be appropriate because of that?

ALBRIGHT: First of all, we have to remember that the WHO is the United Nations organization based on support by the nation states.

And I think that like, every part of the U.N., I think there are questions about it. I have said, now, people and institutions in their 70s need a

little refurbishing, and the U.N. is — has a 75th anniversary right now. And I think people should look into the governance of various parts of it.

There are lots of questions about how the Security Council is operating and the General Assembly. And I do think that the secretary-general is also

being questioned about what he’s doing.

So, I do think is worth looking at. But the point that I wanted to make was, if there are issues, then by the United States deciding that we are

not going to do our part, that we are backing off in terms of paying some of the vol — there’s the required funding and also voluntary funding — we

will not have the influence that we need to have to make changes.

And I had the — similar an experience when I went to the U.N., was that the U.S. was behind on paying some of our peacekeeping bills, and then

Congress unilaterally decided that we would pay less.

And so I didn’t have the kind of leverage that I needed to push for certain kind of reform, leaving the British, our best friends, to deliver a line

they hadn’t — they had been waiting for over 200 years to say, was, representation without taxation, because you just don’t have the leverage.

So I think it was counterproductive generally, counterproductive in terms of what we might want from the WHO, counterproductive in terms of how we

resolve what is a terribly difficult problem.

ISAACSON: One of the issues that requires cooperation is fighting global pandemics.

And, to me, it’s been surprising that this has weakened international organizations, this pandemic. Do you think, coming out of this coronavirus,

we may relearn the importance of having good international organizations?

ALBRIGHT: I hope so.

And I know it’s a cliche to say that every crisis is basically an opportunity, is to really see that the only way to resolve this is by

dealing with others.

So, one of the parts we haven’t even dealt with yet is, what is going to happen in the developing world as the pandemic hits them full strength,

because they don’t have the infrastructure to deal with it or they don’t have water to drink, much less to wash their hands in, or their living

conditions?

And so these kinds of issues can only be solved by partnership.

ISAACSON: The coronavirus crisis has obviously dominated the news and international affairs. But do you think there’s something that’s important

that’s being overlooked at this time?

ALBRIGHT: I think an awful lot is being overlooked, frankly.

I am worried about what the Russians are up to. They — we are dealing, in Putin, with a former KGB officer who has played a weak hand very, very

well, and especially in the Middle East, where we haven’t paid any attention to the kinds of things that are going on in Iran, Iraq, Syria,

Saudi Arabia, the whole aspect of the Middle East.

And then what the Russians are doing to separate us from our allies in Europe, and their behavior just generally, having launched an anti-

satellite missile and various things.

I think what I’m most worried about, though, is — to go back to something, is China. I mean, China — I don’t know how many meetings, Walter, I have

been in with you where we have talked about the rising China and all the various aspects of that.

And I think that they are, when they — when we’re AWOL, they know how to fill the vacuum. And I think we have to be very careful about that. I’m

troubled by the things that they are doing in the South and East China Sea, taking advantage of the fact that we are diverted at the moment.

And then the fact that we’re not paying to so — paying attention to so many other problems in the world, and they require attention and require

our understanding. So, there’s a lot that we’re not paying attention to.

ISAACSON: From your very childhood, leaving what was then Czechoslovakia, spending days of World War II in England with the Blitz happening, and

there’s so many other things that have happened to you.

Compare this crisis and the need for resilience to other things you have been through.

ALBRIGHT: I was a child during World War II. We were in London during the Blitz.

And it was very clear in — at the time how my parents were coping by being resilient. And a statement that I have said about them is that they made

the abnormal seem normal. But resiliency was very important.

And the similarity, Walter, at the moment is that they or the people of England had no control over bombs being dropped from the sky. They only had

control over their own behavior, their mood.

And I think we, as well ordinary citizens, don’t have control over the virus, but we do have control over our behavior, whether we follow the

guidelines, how we approach this. Do we see it as something that has to be dealt with, and not something that we — that our mood doesn’t make a

difference?

Resilience. I do think resiliency is kind of the common theme here.

ISAACSON: One of the things that surprises me as well is that resiliency was part of every other crisis we faced. It’s what happened to the England

during World War II.

And yet, in America, we have polarized so much, even this coronavirus. Even whether or not there would be herd immunity, or even whether or not we

should keep a lockdown on for two more weeks becomes a partisan issue.

Why is that?

ALBRIGHT: Well, I have been so troubled and dispirited, even though I’m trying to control my mood, about the divisions that are being created on

purpose for political reasons.

I have been — I am a political scientist. And I kind of love to study how governments operate and decision-making. And the American system is

endlessly fascinating. The Constitution is fascinating.

People forget that the first article of the Constitution is about the power of Congress. And only the second one is about executive power.

But I think that what is happening is, because we, I think, waited too long to deal with the virus, then you get into blame-placing. And that creates

automatic divisions between the federal government and the states and the governors, or blaming the mayors, or — it’s a blame game, instead of a

solution-finding operation.

And it has been totally politicized, I do think, by the president of the United States, which I find very, very sad. And I have been asked whether I

think he’s — you know, doesn’t believe in America. I think he’s un- American, because he doesn’t understand our value system, our — and only propagates the divisions, rather than trying to figure out how we find

solutions together.

ISAACSON: You have written a new book, which is just coming out, about your life since being secretary of state.

And one of the many things you write about is organizing a group of what you could call Madeleine and her exes, meaning former foreign ministers who

you dealt with, to keep meeting each year.

And I think you met a couple years ago in Versailles. Then you took them to Kansas City this past year. You went from the home of Louis the XIV, who

said, “‘L’etat c’est moi,” meaning, I am the state, I’m in charge, I run everything, to the home of Harry Truman, who had a sense of humility that

comes from being the president.

Is that one of the lessons you feel we should apply today?

ALBRIGHT: I think definitely, because here was a person that had risen to this incredible job through a variety of ways, having served in the

military and had a shop, and then he was very political.

But I think the best thing about him was, he took responsibility. And one of the things that we saw there was the original sign that said, “The buck

stops here,” which he had on his desk, because he knew that being president of the United States ultimately meant that you — that you had

responsibility, and that you worked with others.

So, there are all kinds of lessons from Harry Truman.

I have to say, he was my first American president. We came to the United States November 11, 1948. And he had just been elected in his own right.

And so I followed his life and the way he talks and what he did.

But his clarity and responsibility is something that I think stands out especially.

ISAACSON: You write that, when you read about an international crisis, you reflectively insert your name in place of the current secretary of state,

and think about what you might be doing in this situation.

So, let me ask you, what would you be doing now, if you were secretary of state?

ALBRIGHT: Well, it does make me seem very self-centered. But I am interested in what the secretary of state’s role is and how it works.

I think that I would actually be doing much more to reach out to those that we have to work with, the partners, and really try to work and do kind of a

whole-of-government, from the perspective of the United States, because the secretary of state, with the national security adviser, can set the agenda

and bring in other parts of their governments, as well as — meaning foreigners, that want us to deal with, which would be trying to figure out

how the intelligence community works together.

But I think that we’re not taking advantage enough of the foreign policy capabilities of the State Department, because, in fact, the State

Department has been kind of weakened in a number of ways by the number of people that have left or have been asked to leave, and by the funding of

it.

So I don’t know what the current secretary is doing in terms of trying to help the funding, trying to in fact work with others abroad. I think he’s

done some travel, but it’s unclear what he’s doing.

ISAACSON: You’re famous for writing a book about those pins that you wear. In fact, it even became a traveling exhibition, where your pins went on

displays in museums around the country.

What’s that pin you’re wearing today?

ALBRIGHT: My father was with the Czechoslovak government in exile. And his job was to broadcast over BBC into Czechoslovakia. And he was on BBC all

the time.

And I was a little girl. And I listened to BBC. And I know the following thing, which is, every broadcast open with the notes, the opening notes, of

“Beethoven’s Fifth,” dah-dah-dah-dum.

And, in Morse code, that is victory. And so I thought a V for victory against the virus would be something that is appropriate for today and also

a reference back to my book.

ISAACSON: Secretary Madeleine Albright, thank you so much for joining us this evening. And stay well.

ALBRIGHT: And you too, Walter. Good to have this with you. Thank you.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And one of her books was all about those broaches with a message.

And, finally, coronavirus is causing some major cities to reimagine and rethink the way they’re run. Milan is set to introduce a new scheme to cut

the number of cars on the street after lockdown; 35 kilometers of road will be transformed into cycle paths and walking space.

That Northern Italian city has been hit hard by the outbreak, and it’s one of Europe’s most polluted. But under lockdown, air pollution, as we have

been saying, has plummeted, leaving blue skies.

And so let’s hope it’s a plan other cities can follow, as we strive for a cleaner and greener future.

That is it for our program. Remember, you can always follow me and the show on Twitter. Thanks for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS.

END