Read Transcript EXPAND

HARI SREENIVASAN: Alex, what’s your most recent research showing about the state of misinformation in the time of COVID?

ALEX STAMOS, DIRECTOR, STANFORD INTERNET OBSERVATORY: So, there’s a really interesting thing happening here, which is, for the first time in history, for a very, very long time, all of the countries in the world have the same number one concern. And so we — normally, when we see misinformation from a China, from an Iran, from a Russia, they all have very different areas of focus. But, today, every single country in the world, whether democratic or autocratic, is very concerned with defending their performance during COVID, and, in some cases, of using COVID as a tool against their kind of longstanding adversaries. And what we have seen is a massive shift by countries towards COVID as the topic of the day. Now, in some cases, that’s because they actually have a message they want to push about COVID. So, such as in the Chinese example, there are a lot of messages about the competence of the Chinese Communist Party that they want to push. In the case of actors such as the Russians, it seems like it’s much more opportunistic. Their goal is to use COVID as a hook to pull people in and to build these online communities that they then use for different political purposes later.

SREENIVASAN: So, let’s talk some examples here, giving some examples of how the Chinese or the Russians are using social media now to try to get their point across.

STAMOS: The Chinese example is really interesting, because the Chinese narrative has continued to shift since the emergence of COVID in December of 2019. So, at first, the goal of Chinese messaging was to downplay the severity of the crisis. Then there was a significant shift around the time when the PRC shut down Wuhan and other major cities, in which the messaging shifted to, this is a major crisis, but the Communist Party’s in charge, and the PRC is reacting with incredible efficiency. One thing that a lot of Americans saw during that time was social media messaging about the capabilities of the PRC government. And so I think a lot of people remember the videos of hospitals being built in seven days, videos of drones going around and police in the streets. There’s a kind of a viral video about a drone yelling at a grandmother to go back home. These were videos meant to show that the Chinese Communist Party has organized China in a way that gives them great capabilities, but also to kind of subtly reinforce the idea that the authoritarian control of China is perhaps in the best interest of the rest of the world, because it allowed the Chinese to contain it. Since then, the Chinese have pivoted now to be very, very anti-American. And you see an official line about America handling the COVID crisis very poorly. Unfortunately, the things they’re saying are generally true, right? So it’s hard to call it disinformation. They’re just highlighting actual failures in American policy. But the other more covert messaging is around the idea that the virus did not actually arise naturally in Wuhan, but is an American weapon. And so that’s been a much more kind of insidious and quiet message that they have been trying to inject, is to raise doubts about the idea that this is a virus of Chinese origin and trying to start to come up with alternative theories that they’re planting in alternative media, in certain kind of conspiratorial groups online, to help — to convince a number of people that perhaps it’s not as simple as this coming out of a Wuhan market, which I believe is still what scientists have — believe is the most likely explanation of where the virus has come from.

SREENIVASAN: So how are they taking that message? Is that something that the Chinese government is sending to its own citizens, saying, hey, this could be America’s fault, or are they trying to send that to American citizens and everyone else in the world?

STAMOS: It’s both. The Chinese propaganda capabilities are quite different domestically vs. foreign. Domestically, the Chinese have what they call the 50 Cent Army, which — referred to informally as the 50 Cent Army, which is a group of people who have volunteered to push the Communist Party and the official government’s propaganda. And they receive messaging that allows them to flood lots of channels in Chinese language with that messaging. Those people generally don’t speak English or any other language. They are not very effective in pushing propaganda elsewhere. So, outside of China, you often see these messages being pushed either by the official state media organs, like CCTV, CGTV, Xinhua and with the like, or by representatives of the Chinese government who are just asking questions on social media. And the target is sometimes Americans. But it looks like to us that the majority of the English language content that the Chinese state media are pushing is really meant at the rest of the world. And it seems like there’s — one of their goals is to erode American soft power and to build up Chinese soft power. They are using this as a opportunity to highlight the ways that China has reacted well and the United States has reacted poorly. They’re also highlighting the ways that China is exporting aid. And so if a plane lands in a country in Africa, that will be highly, highly touted across the continent in a variety of languages by Chinese state media of, look, while America flounders, China is helping out the world.

SREENIVASAN: The idea that the United States is responsible for the coronavirus, is that a response of escalation to United States saying that perhaps the Chinese started this virus in a lab and pushed it out or it escaped?

STAMOS: It’s possible. I don’t think you can understand the Chinese actions without also looking at the actions of President Trump to blame the Chinese for the virus in ways that have not been supported and to try to shift global responsibility onto the country where it initially emerged. And you’re right. I think a lot of this is responsive and is part of their — it’s part of their plan to blunt some of the criticisms from the United States. And so I do think it’s — there is a certain amount of this that you have to consider fair. When the president of the United States is able to get on stage and to say things about China that are — many of which are not true, and then to have that covered by free media, then there is some need, if you’re the Chinese, to fight back with state media or paid media.

SREENIVASAN: Where are the Chinese advertising these messages in the United States?

STAMOS: So, in the United States, they are advertising on social media, mostly on YouTube and Facebook. And so these companies have policies around covert propaganda. They have policies that you cannot go create fake groups , create fake accounts, push narratives from fake identities. These identities do not lie about who they are. It says right there that they are Chinese media outlets. Now, some cases, they’re not explicit about their link to the Chinese Communist Party. But any China watcher understands that these are official media organs. And they are spending money to amplify their message on American platforms.

SREENIVASAN: So, the social media companies are taking advertising from Chinese state actors to spread disinformation?

STAMOS: So, it’s not always disinformation, to be clear. A lot of it is true fact that is manipulated and interpreted in a way that pushes the edge. But we do have to be careful. I would say it’s safely propaganda. But, yes, they are taking money to amplify these messages from Chinese state actors. One of the great ironies here is that Facebook and Twitter and YouTube and all the other major American social networks are blocked by the People’s Republic of China, and so that the Chinese people do not have the ability to go on Facebook and criticize their leaders. But Chinese state media are able to use Facebook to reach out to the world to push their message. I think there — that asymmetry is something that needs to be looked at.

SREENIVASAN: About Facebook — I know you work there for a number of years — is there enough incentive for Facebook to take misinformation and disinformation off the network, regardless of whether it’s a state actor or it’s an individual or a group that is spreading falsehoods?

STAMOS: Facebook and the other companies have been much more aggressive about taking down speech by actual Americans that they deem to include dangerous theories about coronavirus. So, for example, you can’t — you’re not supposed to be able to run an ad that says, buy bleach, bleach will — by drinking bleach, you will kill coronavirus, right? And so they have taken those steps on things that are clearly factually inaccurate. But, on this kind of issue, it becomes difficult for them to have a content-based policy, because the stories, when you look at especially what the Chinese are pushing, are somewhat subtle in how they’re propaganda. They’re not including crazy claims, like eradicating yourself with U.V. will kill the virus. And they are actors who are explicitly who they are. And so it’s kind of finely tuned to go around all the policies that the companies have created to keep them from wading in, from making political calls. Our position is, in a situation where a country is known to be an autocratic country and is known to be manipulating social media in a way to control their own populace, in those situations, you can make rules that apply only to those actors, even if the content itself is not that controversial. And I think that’s the direction they need to go here is, they need to add another category of propaganda they’re looking for not, just propaganda from fake accounts, not just propaganda that’s harmful, but propaganda from actors that are aligned with autocratic states.

SREENIVASAN: Recently, the Federal Trade Commission lobbied a fine, $5 billion, against Facebook. It was just approved. It’s the largest fine in history for the FTC. But a lot of people look around at any of the financials for Facebook and say, that’s relatively a drop in the bucket for millions of people’s information being shared inappropriately through actors like Cambridge Analytica and others. Does it make a difference?

STAMOS: So, I don’t actually agree with the FTC’s goal here. The FTC is supposed to both look privacy issues, but also competition issues. The truth is that the Cambridge Analytica scandal is one of the most overblown privacy scandals in history. It’s somewhat of a media — the media is very focused on the scandal, and then skipped some actually impactful ones. Like, last year, we found out that most of the major phone companies in the United States were selling people’s GPS locations. This was a story for like a week. It’s still going on today, right? And that’s much, much more impactful than Cambridge Analytica. And the problem is the FTC is chasing the media. They’re chasing the story. And the focus on Cambridge Analytica obscures the fact that the APIs that were abused in the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the interfaces to get to Facebook’s data, are also the — one of the only mechanisms by which you could have a competitive social network. And so there’s a balancing act here between requiring Facebook to keep data private, but then also requiring Facebook to allow for competition to exist. And that’s the balance that I think the FTC has missed in their consent decree. The amount of money is not what matters. What matters is the rules that they are supposed to follow. And if you look at those rules, they have effectively created for Facebook a get-out-of-jail-free card for competition, because the FTC has required them not to create mechanisms by which other companies can access Facebook data. And as the ownership of that data is the — is the ownership of the social graph that gives Facebook its dominant position in the space. And so I think the FTC is actually really aimed in the wrong direction. And it’s the mass U.S. media that’s driven this by focusing on Cambridge Analytica, and not all of these other issues that are much more quantitatively impactful in people’s lives.

SREENIVASAN: While you’re a consultant for Zoom today, you have worked at most of the big tech companies at some point. You have a relationship with them for years. Knowing what you know now and having been outside of that for a couple of years, are the tech companies in Silicon Valley better prepared now to prevent what happened in 2016 from happening again at the 2020 elections?

STAMOS: So, I think the companies are better prepared for exactly what happened in 2016. The question is, is that relevant to 2020? What we have found in our research is that the Russians have changed how they’re acting and other countries act in very different ways from a propagandist perspective. So the same Russian groups that used to create hundreds of fake accounts and run them from St. Petersburg will now do things like hire locals to post under their own names, but to post Russian propaganda. So one of the reports we have written in the last year was about this kind of activity in Africa, that we found people related to Yevgeny Prigozhin, who is the Russian oligarch who ran much of the propaganda campaign in the U.S. 2016 election, that his teams are going out, and they are finding locals in Egypt, in Sudan, in Madagascar, who then are acting on their behalf and are creating content that is culturally and language accurate and specific, but is pushing pro-Prigozhin propaganda. And so that is much harder to defeat, right? And that is why I think that companies need to have a much broader view of what propaganda looks like, and also have to be really careful to work with democratic governments on trying to pull back the veil on these kinds of groups. The other issue I’m really worried about is the focus of the Russian propaganda in 2016 was about driving divisions in the political positions. My fear in 2020 is that their goal will be to invalidate the election, that their goal will be to make people believe that the election was rigged in one way or another. And I originally thought the way they would do this would be by hacking the election systems. That’s something that has not improved that much since 2016. There are good people in the federal government working on this issue, but they don’t have a lot of power to get localities and states to act in a secure manner or to cooperate with one another. And so we have some fundamental changes that need to be made. It’s honestly too late for 2020. This is something that Congress should have taken up in 2017. There were bills, and they were all blocked by the Senate majority leader. So it’s really unfortunate Congress hasn’t acted. And so, because of the insecurity of these systems, and the fact that we might have a highly disruptive election because of COVID — we are going to have people doing lots of vote by mail, people not showing up in person and doing absentee because they’re afraid of the virus, this creates kind of an underlying unease about the validity of the election already that I’m afraid Russia and other countries might step into.

SREENIVASAN: Alex Stamos, thanks so much for joining us.

STAMOS: Yes, thank you, Hari.

About This Episode EXPAND

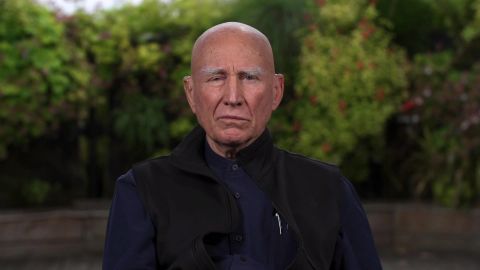

The president of the European Commission tells Christiane Amanpour about a global fundraiser for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado explains the pandemic’s threat to indigenous populations in his country. Alex Stamos, director of the Stanford Internet Observatory, discusses U.S.-China relations and the dangers of disinformation campaigns.

LEARN MORE