Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Next, we have an exclusive interview with the first African-American to serve as director of the Defense Intelligence Agency that was under President Obama. Lieutenant General Vincent Stewart retired last year after nearly four decades of service with the U.S. Marine Corp. After George Floyd’s death, he felt compelled to speak up for a future of generations of black American in an op-ed called “Please Take Your Knee Off Our Necks So That We Can Breathe.” And here he is speaking with our Walter Isaacson in first TV interview since he wrote that article.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane. And General Vincent Stewart, welcome to the show.

LT. GEN. VINCENT R. STEWART (RET.), FORMER DEPUTY COMMANDER, U.S. CYBER COMMAND: Thanks, Walter. Yeah. Delighted to be here.

ISAACSON: Tell me your feelings as you watched the video of George Floyd being murdered.

STEWART: Two images that are burned in probably forever. The first image is probably early in the confrontation, and you see the two pictures, the two faces, Officer Chauvin on top, George Floyd on the bottom, having Officer Chauvin’s knee on his neck. And the image of face — the expression on Officer Chauvin’s anger, dominating position, just in total control of the situation. And you look at the image of George Floyd on the bottom, fear and great concern for his position that he was in, that it’s such a juxtaposition of the dominance of one and the fear and dread of the other. Fast-forward, about eight minutes later, and you look at George’s image. His eyes are closed, his body is lifeless, and I don’t know if he’s dead at that point, but the expression is different. And Officer Chauvin on top, very calm, very nonchalant, very much in control. And three images when you see them, if you’re not touched by those images, I would question your humanity. And that’s a harsh statement. And I think every African-American who saw that had to have been touched. Every American who saw that should have been touched. And at that moment I realized that I could not be silent anymore.

ISAACSON: You had spent a career in the military, rising to the top ranks, becoming a general at the Defense Intelligence Agency and many other places. But then you decided you had to write an article, something you really hadn’t done much before, speak out on race. Why?

STEWART: There’s two parts, one, that incredible image. But the hard — it wasn’t courageous to write that article. It was painful. And the painful part of it was, in spite of all the things that I had endured, I could not protect my children from enduring bigotry and hatred and racism. And if, in 2020, we’re still following the pattern that we’ve had throughout the history, my grandchildren would not be protected. I have 15 grandchildren, all ages, size, demographics. We are the American dream. But I have got a young granddaughter who I’m thinking, goodness, we’re going to keep doing this cycle over and over again. And I may not be able to protect her. And, again, that’s the reason I had to speak up. I would not have been credible speaking up as a captain or a major. I was certainly credible as a retired three-star, former director of the DIA. Folks would listen, and it might make a difference.

ISAACSON: Tell me about the title you chose.

STEWART: There are a couple of things that happens if you have your knee on our necks. Well, the first thing that happens is, you will die, like George Floyd. If you are being suffocated, you will die. If you take your knees off our neck, we will contribute to the greatness of this country. We will contribute — we will be — participate in this democracy. We will help this country, because we have diversity, not just the diversity of color, but diversity of thought and ideas. So, you have a choice in this case. Let us be part of this environment. Let us be part of this democracy. Let us be helpful in making America truly live up to its ideals, or wipe us all out, kill us one by one, and not have the contribution that we can add to this society.

ISAACSON: In your op-ed, you write: “It’s hard for me to explain the pain.” What is it you have faced? Can you tell us about that?

STEWART: It’s incredibly painful to think that, if I were — and it doesn’t happen now — when I was younger — I’m outside the demographic that gets attention — that if I were — if I thought I was going to be stopped by a police officer, I didn’t think that police officer was going to be my friend and we would have a trusting conversation. I believed that I was, at that moment, in a confrontation, a fight-or- flight environment. And so how do you protect yourself? You make sure your stop is under a streetlight, where someone will see you. You make sure the stop in an environment where others might see you. And to live that every day, to just — in almost exasperation, just go, OK, I’m going to be stopped. I know I’m going to be stopped. How am I going to deal with it? Am I going to try to get out of there? Am I — how am I going to be deferential to this officer so he knows I’m submissive right from the very beginning, even if I have done nothing wrong? And to live that every day, and to try to convey to another demographic that this is the life of an African-American, even today, that you’re going to be stopped for no other reason than someone wants to ask where you came from, where you’re going, but the underlying issue is, you’re a bad person, and I need find out what you have just done wrong, so that I can take you to — and that’s hard to live.

ISAACSON: The most powerful parts of your piece were where you describe your own — things that happened to you, first when you go to Chicago, emigrate there from Jamaica, and then step by step how you got touched by racism. Describe some of those for me, please.

STEWART: Yes. I remember my first — my first fight in America was racist. And this was a young man who I ended up playing on the same football team. We were at the park in the North Side of Chicago, a bunch of us who looked like me playing baseball confronted by a bunch of folks that didn’t look like me. And I don’t even know why we even started the argument, but we ended up in a pretty good brawl. And that was the first time anyone ever — as far as I remember, the first time someone used the N-word in a confrontation. And I can’t tell you how many times I have seen folks who, in anger, immediately default to N-word. And that genuinely tells me what’s in their heart. It would be one thing to call me out and go, you’re tall and you’re ugly or you’re fat or whatever. But they default to that word, which has a very specific connotation to it. So, that first fight was the first fight, the first time I have ever been called a nigger. And it struck me at that moment how different my environment was. And this was maybe my first freshman year in high school.

ISAACSON: Then you joined the U.S. Marine Corps. And one of the sayings in the U.S. Marine Corps is that there are no black Marines, there’s no white Marines, there are only green Marines. Was that your experience?

STEWART: I think that was the ideal. But we draw in the Marine Corps from a cross-section of society. So there are probably people who believe that performance is the only thing that matters. But there are also people, because we draw from society, who thought, yes, but he is a dark green Marine, and that makes him different than a light green Marine. I think the Marine Corps generally tries to emphasize, if you deliver, if you perform, you will move up by merit. But, again, we have folks from all sections of society. So I’m not naive enough to believe that during my time in the Marine Corps that I didn’t encounter people who had some level of bigotry and some level of hatred, some level of superiority, some level of racism.

ISAACSON: Why are there not more black officers in the Marine Corps?

STEWART: On the enlisted side, we have done a remarkable job. I’m not sure I understand why — you look at the enlisted demographics, and it looks pretty good, all the way throughout, all the way to the top of the pyramid. You look at the officer side, and go back, we’re not recruited enough at the base. And we’re doing targeted retention. But if we’re serious about getting people to the top, we got to have some different approaches. It’s not going to happen organically. It’s not going to happen because you don’t have a base. It’s not going to happen if you don’t target recruiting and if you don’t place some jobs that will make them competitive. What I challenge everybody, both in the private sector and the military now, is, take a look at who is in your front office, because the people who are in your front office are your future leaders. They’re exposed to the senior decision-making. They’re getting their evaluation written by three-and four-stars. They are other general officers who are going to sit on their boards and recognize them. And so if the demographic in your front office looks like one particular demographic, then we shouldn’t be surprised when they show up on the command list and when they show up on the general officer selection list.

ISAACSON: The George Floyd death, murder, and COVID-19 both could have led to conversations that you talk about that would have united us, that would have brought us forward, as you say. Do you think our national leadership is conducting those conversations in ways that unite us?

STEWART: No. And I guess I should probably help define that. Those are two great examples where, if we wanted to bring America together, we could galvanize America around two really serious issues. Instead, it’s become partisan and divided. And it’s continued a path of division that cannot be healthy for our nation. I could imagine truly going to war against the pandemic and making this a unified approach to how we defend our nation against this virus. But you now see blue and red states and how they’re doing in terms of dealing with it, and both sides are on different approaches to solving this. So, national leadership is — I think we lost an opportunity to bring the nation together in this — both in those cases, both in terms of the pandemic and in George Floyd. And I think that’s to the detriment to our nation.

ISAACSON: When you retired, you said you did it partly because you were just tired. But was there something else in it that made you say, I have got to leave, I’m not comfortable with the leadership?

STEWART: I left because I was tired. I left I — because friends my age were dying. And I wanted to spend more time with my family and my grandchildren. I also — I don’t know that I could have — one of the things I worry about is the politicization of our military leadership. When I see the chairman — and I know the chairman did not want to be where he was, but I see it too many times, where we rolled out our chairman and chiefs of staff as a backdrop to something that is political in nature. And I could see that coming, and I did not want to be a part of that. I think it’s absolutely dangerous to our society and our democracy that our military is politicized. And, sadly, our leadership sometimes don’t have a choice. If our political leaders say, we want you at the White House to be there, they probably are arguing that we probably shouldn’t be there. But if the commander in chief says, you should be there, guess what? You have got a couple choices. You can walk out the door and go, OK, I can’t do that, I don’t support that morally, or you can show up, because your commander in chief says, show up. And so you get a really tough choice. I can walk out the door or I can go be a prop. And I can the anguish and pain when the chairman and the chiefs are standing there. They’re trying to be stoic. They’re trying not tip, yes, I gree, or, yes — no, I don’t agree. But I didn’t like the idea of being a prop, as I think a misuse of our military leaders. So that was a factor in my going home.

ISAACSON: When you talk about being a prop for the misuse of the military by our political leaders, are you also thinking about what happened in Lafayette Square, when the president cleared it out so that he could stand for that photo-op?

STEWART: I think that was a terrible position to put the chairman in. And, yes, if you’re talking about rolling out the military to suppress peaceful protests, and you’re willing to use military, what better — from a political standpoint, what better way than to have the chairman be there as part of that message? And I know General Milley didn’t want to be there. I know he probably regrets to this moment being there. But I thought that was a terrible, terrible optic. And I don’t know that he had much choice in the matter. But that sends a terrible message to the American people that we’re ready to use our Army to suppress a peaceful protest. It was a bad place. I’m very glad I didn’t have anything to do with that.

ISAACSON: What’s at stake, in your mind, in this election?

STEWART: I’m going to steal from Jon Meacham’s book, the soul of America, the soul of America. And we have been wrestling with this throughout our history. Who do we really want to be and what do we want to represent, not only to our children here at home, but to the world? And that, to me, is what this election is all about. It’s, are we going to be the bright light on the hill? Are we going to preach to countries about human rights and rule of law and justice, and then we hold a mirror up to ourselves and we’re going, we’re not just, we don’t necessarily buy into the rule of law, we are doing things that make us look like bullies on the international stage? Nations around the world have got to be looking at this thinking, how hypocritical. What a different set of standards. So, if we can’t be the example — and I ended my piece with, I still believe in America, but America will be great if America is good. And America will be great if we’re an example to the world. America cannot be great if it is being as hypocritical on the international stage. America cannot retrench and not be of this global community. The world has always needed what we stood for from the beginning of our Declaration through our Constitution, warts and blemishes and all. We have got to be an example to the world. And right now, we’re not a really good example. So, for me, that’s what’s at stake this election.

ISAACSON: General Vincent Stewart, thank you so much for being with us.

STEWART: Thank you very much.

About This Episode EXPAND

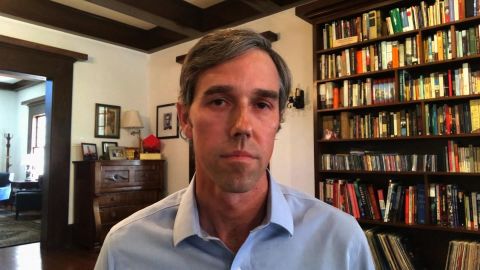

Christiane speaks with Beto O’ Rourke about the politics of coronavirus in his home state of Texas. She also speaks with The Atlantic science writer Ed Yong about the latest on the virus and musicians Margo Price and Jeremy Ivey about Price’s new record. Walter Isaacson speaks with retired three-star General Vincent Stewart about why he chose to speak out about racism.

LEARN MORE