Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

Coast to coast crises and still trailing in the polls. Trump loyalist, Michael Anton, tells us why he thinks the president does deserve four more

years.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: They only see the side they want to see.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The heartbreak and hope of Gaza. Producer Brendan Byrne joins us with his film, on the human side we almost never see.

Plus —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MELINDA GATES, CO-FOUNDER, BILL AND MELINDA GATES FOUNDATION: We’re going to have a lot of building back to do, a lot.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Philanthropist, Melinda Gates, delivers a stark warning, poverty and hunger rise as COVID brings global progress to a grinding halt.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

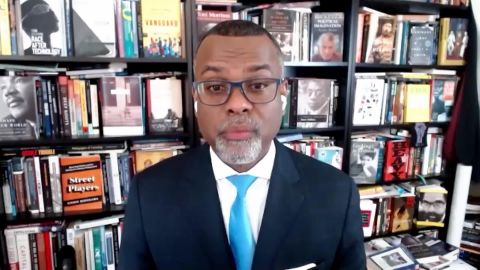

EDDIE S. GLAUDE JR., AUTHOR, “BEGIN AGAIN”: There’s nothing about the belief that white people matter more than others that can be salvaged.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Professor Eddie S. Glaude Jr. tells our Walter Isaacson how James Baldwin has rescued him from politically despair.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

President Trump has less than 50 days now to court votes ahead of November’s election. He’s crisscrossing the country. And this week in

California, he displayed his climate science denial. Here he is talking to a California state official.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: If we ignore that science and sort of put our head in the sand and think it is all about vegetation management, we’re not going

to succeed together protecting Californians.

DONALD TRUMP, U.S. PRESIDENT: OK. It will start getting cooler. You just watch.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I wish science agreed with you.

TRUMP: I don’t think science knows actually.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, that was about the wild fire crisis. And it comes as he also shows doubt on coronavirus science. The Pew Research Center today reports

America’s standing overseas has plummeted over its coronavirus response. So, perhaps the president and his allies can take a breather from the

country’s dueling crises amid a special White House ceremony marking the normalization of ties between Israel and two of its regional Arab

neighbors, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TRUMP: We’re here this afternoon to change the course of history. After decades of division and conflict, we mark the dawn of a new Middle East.

Thanks to the great courage of the leaders of these three countries. We take a major strive towards a future in which people of all faiths and

backgrounds live together in peace and prosperity.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now, my first guest tonight, Michael Anton, has worked closely with President Trump as a former national security council spokesman. His

new book is called “The Stakes.” And he joins me now from the White House where he was invited to witness that ceremony we have just seen.

Michael Anton, welcome to the program.

You must be breathing a little sigh of relief, because here’s a spotlight on something that’s being portrayed as a success and that has received some

kudos. Just tell me what you think this signing ceremony will do? What is its big, big meaning to you right now?

MICHAEL ANTON, FORMER U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL SPOKESMAN: Well, it’s the first normalization between Israel and an Arab state in a quarter of

century and it’s not just one, but it’s two Arab states in the span of a month. Although to be realistic, these things take much more time than a

month to work through.

I think it means a lot of things for regional cooperation, economic cooperation in the Middle East. It means a lot — it has a lot to do with

this emerging anti-Iran alliance that has brought the Arab states and Israel close together because they both have the same concern, and it’s

possible that this could be a real milestone toward achieving peace between Israel and the Palestinians. You know, there are sort of two views of how

you approach that as a negotiator from the outside.

In the old way, which presidents of both parties tried, was get it to direct talks between Israel and the Palestinians early and often. And this

way is — well, what happens if we talk to the Arab states around the Palestinians? Everybody knows that a final deal can’t really be made

without the support of the Arab states who will need to legitimize it, who will need to encourage the Palestinians diplomatically and frankly, who

will need to pledge them economic and other kinds of aid to prop up the Palestinian state.

So, when these very powerful, rich and influential Arab states make a deal with Israel, I think you see peace between Israel and the Palestinians more

and not less likely. Now, you know, no one can say when. This has been an open and very, very challenging issue for a half century or more, but I

think we’ve taken a step in the right direction with this deal.

AMANPOUR: So, to be fair, I mean, it’s interesting that you mentioned the Palestinians because almost nobody on that platform did and they’re not

obviously invited to the ceremony today, and they’ve broken off relations with the U.S., as you know between than I do, over the issue with

Jerusalem, et cetera.

Some have suggested, as you know, also, the UAE And Bahrain never had any war with Israel. So, it’s not really a peace agreement, it’s more of a

normalization.

ANTON: It’s normalization, yes.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Great for Israel to feel that it is more surrounded by friends rather than enemies in the region. Some have suggested now that the

Arabs if they’re at a table with Israel, if they increase normalization relations, they will be able to put the Palestinian case more emphatically

with Israel rather than Israel being outside. Do you foresee that being a possibility?

ANTON: I expect that. And if I recall correctly, the foreign minister of the UAE in his remarks did mention the Palestinians at the ceremony just

now. I think you’re right, that they will probably try to get the — at least, I hope you’re right. I think that when the president recognized

Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, he only stated reality on the ground. There was point zero chance that in a final status negotiation Israel was going

to move its capital. By recognizing that reality, he was trying to move the process forward so that the parties could talk about the core issues that

really still divided them and were between them.

I think that the Palestinian leadership did their people a disservice by walking away from those talks. I expected or hoped at the time that that

walking away would be temporary, maybe it would last months, weeks or months, and that temperatures would cool and people would come back and

stop talking. It’s now been, by my count, about almost three years, if I have that right, and those talks haven’t been taking place.

I don’t think that that’s constructive for the Palestinian people, and I hope that this ceremony today and the reality that underlies this ceremony

will begin to change minds on that point, for all parties concerned.

AMANPOUR: Well, it will be interesting and we’re sure that there will be more Arab states joining, as the president said, and as our own sources

say. But on the Palestinian issue, I mean, as you know, nobody expected Israel to move its capital from Jerusalem, but under international

agreements, it’s meant to be shared in a final peace agreement. On the issue of peace, Anton —

ANTON: Well, look, the movement of the United States embassy into Jerusalem does not in any way prejudge any kind of final status. All the

final status questions that you’re talking about were still open when the president made that announcement and they’re still open now.

AMANPOUR: Right, and, you know, sadly for Jared Kushner, who worked so hard on a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians, that hasn’t

actually come to fruition. Now, I want to ask you this. You know, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu today said, let’s not be cynical, let’s look

towards the future and towards hope and peace.

So, we’ve already established that the Palestinians’ peace hasn’t been addressed yet, and the countries who went into this deal now, the UAE,

Bahrain, well, certainly backed by Saudi Arabia, UAE, have been at war against Yemen. There is no mention of Yemen, there is, you know, thousands

of Yemenis are being killed by that U.S.-supported air campaign against Yemen. Where do you see that leading? I mean, you know that in Washington

where you are right now, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are not very well thought of in Congress because of this war.

ANTON: Well, I can tell you who is thought even less of in Congress and that’s Iran, who you didn’t mention in this context but —

AMANPOUR: Well, we haven’t gotten there yet.

ANTON: Iran is the big foreign driver of the Yemeni war. And Iran’s actions, destabilizing and destructive actions in the Middle East, as I

said earlier, and I will repeat, I think it’s an important point, are a big part of the reason why these Arab states are willing to normalize relations

and have closer cooperation with Israel, because they recognize a common threat and a common interest.

So, the Yemeni problem is fundamentally an Iran problem, and this is one of the reasons why the president has been so tough on Iran and sanctioning

Iran. In part, he wants to reduce the amount of revenue and resources the Iranians have to use to destabilize the region.

AMANPOUR: So, you brought it up, and I want to bring it up too. What would a Trump 2.0 foreign policy look like? And let’s take Iran first, because

clearly, certain decisions were taken. He pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal, and yet, even with this policy of maximum pressure, as he calls it,

he has not changed Iran’s behavior nor has he caused, as he said he would, a reopened negotiation and a better negotiation. That hasn’t happened. It

just hasn’t happened. So —

ANTON: I would dispute the contention that he hasn’t change Iranian behavior. I think Iranian misadventures oversees, they haven’t stopped but

they’ve declined and part because they’re (INAUDIBLE) and in part because they lack the resources that they would otherwise have if the money was

still flowing under the old deal.

But I think what the president would like to see in a second term is a new Iran deal, if the Iranians are open to that, but one that doesn’t sunset

and that doesn’t leave lots of loopholes for supposedly peaceful nuclear activity, but it’s much more airtight and it really prevents an Iranian

bomb for all time, not just for 10 years.

AMANPOUR: Let’s just get this straight. You know, Iran is still heavily involved with Hezbollah and with Syria, and inside Iran, the hard line has

been empowered since pulling out of the Iran nuclear deal, as you’ve seen with executions and with imprisonment of human rights activists and other

opposition, very, very much empowered.

So, I just want to ask you then, what — and also, your European allies are not coming to President Trump’s position of putting international sanctions

back onto Iran. So, I’m still trying to figure out where this administration and how this administration plans, because it does seem,

you’re right, that the key issue for President Trump overseas has been Iran, and that’s where this whole realignment of the Persian Gulf region

seems to be about. How does the president plan, or how is he being advised to plan an Iran policy?

ANTON: Well, I can only tell you what I know from public statements. He’s going to keep the pressure on to reduce the resources that the Iranians use

to spread mischief in the Middle East, and he’s going to continue diplomacy that brings Arab states that reinforces America’s alliances with the Arab

states and that brings Arab states and Israel together to increasingly isolate Iran in the region. And I think the president’s hope, if I may

speculate as to what I think his hopes are, is that that pressure will — may be convince Iran, perhaps somewhat painfully, but convince Iran that

it’s the on the wrong path and it needs to change course.

In the meantime, though, you know, the president’s paramount concern is reducing the ability of Iran to harm U.S. interests overseas and U.S.

allies, and he’s done that by, again, cutting the flow of resources. Now, you mentioned the European allies. I know that they disagree with the

president’s policy on this, but let’s be honest with ourselves that there – – some of their reasoning may be high minded. Some of it is also a bit cynical, which is that there’s a lot of big European companies that want to

do business with Iran that very reluctantly agreed to the raft of sanctions that were put together after the nuclear disclosures of 2002 and were quite

happy to see those sanctions get lifted under the terms of the Iran deal and don’t want them to come back. Not out of any geostrategic or

geopolitical reason fundamentally, but because there’s a lot of revenue streams potentially lots at stake here.

AMANPOUR: Michael Anton, you’ve written the book, “The Stakes,” why you think the president should be reelected. I also want to ask you in talking

about your book, do you think — because he has portrayed himself as a disrupter and he has raised the states, so to speak, he has, you know,

pressured, for instance, the NATO alliance. Some in his own administration, many of them left, obviously — I mean, who have left, not the left wing,

but who have left, suggested he might in a second —

ANTON: Maybe both.

AMANPOUR: — turn, pull out of NATO. Do you think that is a likelihood, a possibility and would it be wise?

ANTON: Well, I think that the threat got NATO’s attention, and so you’re seeing NATO members meet their commitments in a way that you haven’t in a

long time. NATO members got used to hearing American presidents say, you all need to spend more on common defense and work more withing the alliance

and make it real, and then not follow up and there being no consequences. So, NATO members got — they knew that they would hear the lecture and they

wouldn’t have to pay the price if they ignored it.

Trump is the first president to make them fear that there might be a price if they ignored it and they starting to step up. My sense from talking to

the president about — I haven’t talked to him about NATO recently, but I went on his first trip to NATO and I’ve heard him talk about it many times,

is that as long as he sees NATO members stepping up, meeting their commitments and doing what they’re supposed to do, he’ll stay in the

alliance as long as he thinks the alliance is working for the American people.

If things slide backwards, then who knows. You know, he’s typically not the type to telegraph his punches. He does a little bit, but he’s also a bit

unpredictable, so I don’t think he’s going to, you know, give some kind of ultimatum. But if the trend line is what he thinks is working for America,

he’ll be pleased with a the alliance, if he sees the trend line go the other way, I think he’ll start to revisit and you might hear some of the

NATO skepticism talk that you heard a lot of in 2017 return to the fore.

But so far, the direction has been good and I think — and, you know, Secretary General Stoltenberg said this to the president on that first

trip, he said, you know, your badgering them — has helped. It has helped them. He said, I — the secretary general, I’m always on them. I want them

to meet their commitments, I want them to invest more, I want them to be involved, and these governments don’t want to do it. And, you know, you

came along and put a fright into them, and it’s been really helpful. That’s what Stoltenberg said.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And just very finely. I mean, obviously, that all started in 2014 under Obama, but I understand what you’re saying. But I wanted to

ask you this. If, if there is a decision in a second term to pull out of NATO, do you think that would be wise? Because don’t you think that would

empower and embolden, like America’s adversaries, and your book “The Stakes” is about adversaries, domestic and foreign. Do you think that would

embolden people like Russia who really want to see that happen?

ANTON: Well, look, I don’t want to speculate about hypotheticals. The United States has been — I mean, NATO was founded in 1949. You could argue

that if they were going to go out of business, the time for it to gone out of business was with the collapse of the Warsaw Pact in 1989. The alliance

was maintained in part because it’s very difficult to build these alliances and these interoperability rules and all of these things and it’s been

utilized a few times. And so long as the alliance is working in the interests of the American people and American foreign policy, America

should stay in it.

But, you know, as George Washington said in his farewell address, no alliance should ever be permanent. Once it stops serving your interests,

you need rethink it.

AMANPOUR: And so far, it hasn’t of course. They came to America’s rescue, the very first time Article 5 was ever declared after 9/11. Michael Anton,

thank you so much, indeed, for joining us.

Now, Washington is celebrating Israel’s deepening ties with the Arab world, but Israel’s closest neighbors, as we’ve been talking, the Palestinians,

are feeling somewhat betrayed. There is still no Palestinian peace deal and occupation and settlement building continues. Middle Eastern politics with

its various power dynamics and even violence is, indeed, complex.

But behind all of that is something simple, and that is the lives of everyday citizens who laugh and laugh, and dance and sing and just want to

be normal. It is an unusual view into Gaza, but a new film called “Gaza” is showcasing this very human side of life there. And Producer Brendan Byrne

is joining me now about it.

Brendan Byrne, welcome to the program.

Let me just ask you because you know better than anybody that the idea of humanizing, you know, a population that is seen as so — or at least their

leaders are seen, you know, so negatively by so many around the world is a risky product, a risky project. Why did you decide to go into Gaza and tell

this story of ordinary people?

BRENDAN BYRNE, PRODUCER, “GAZA”: Well, you know, for some of the reasons you said, I mean, I grew up in Northern Ireland. I grew up in the years of

conflict here, and, you know, I understand intrinsically what injustice feels and looks like as being part of the minority community myself. And

when a fellow Northern Irish guys and another colleague from the Irish border had teamed up and had gone into Gaza on a number of occasions and a

photographic project and started filming there and brought me the material and asked me, was I interested in exploring this further, I immediately

connected at a very human level with these kind of very ordinary, yet extraordinary stories of real people who had become fierceless in many ways

through the television news and the three-minute news clip.

And here were these beautiful, articulate, but often sad, yet passionate people who were really just crying out for their voice to be heard and

their stories to be told. That really resonated with me, and for that reason we decided embark on this film, which has been a great journey of

learning and understanding for all of those involved.

AMANPOUR: I want to play a little clip. It actually comes right at the top, almost right at the top of the program, of the documentary, and it’s

this little girl, Karma, and she’s a teenager, and she loves to play violin but she has a statement about the state of her people and herself in Gaza.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

KARMA KHAIAL: People from the outside countries, they can’t see other than the fact that we live in constant wars. The only thing they give us is,

like, sympathy, and it bothers me so much. They only see the side they want to see. They should look deeper.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now, Karma is, in fact, a cellist, not a violinist. She wants to go abroad. She wants to study politics and law. But she’s kind of trapped.

You know, your film starts with the facts that Gaza is besieged by both the Israelis and the Egyptians, and that there are some, I think, 2 million

people there in a small piece of land along that Mediterranean Coast.

Were you surprised? I think many people have been surprised. It’s got a lot of good reviews, certainly, from Sundance. Some, you know, say that — some

negative, and will go into that. Do you think it’s the surprising ordinariness of life there that has caused the views that have come out

about the film?

BYRNE: Yes. In many ways, it’s not easy, really, to get into Gaza for any length of time as a foreigner, and any films that have come out of Gaza,

you know, “5 Broken Cameras” and other films have been made from inside, and actually to create a portrait of a place and it’s a debate we often had

in Ireland here, you know, is a film made of like a place better from an inside or sometimes better from someone coming from the outside, and those

two different types of people make two different kinds of films.

I think people have been kind of anesthetized by little short news reports and being bombarded literally by scrappy news reports of bombs and chaos

and all sorts of attacks, and never does anyone get a chance to hear the ordinary people’s lives and the ordinary people’s plights. And to present

that in a way in a mosaic where you have young and old, male and female, aspirational and those happy to stay, all set within a very cinematic

context with a beautiful score kind of elevates the story to a place that maybe hasn’t seen before on a wider scale, and especially in a cinematic

context. It’s very beguiling and very engaging to many people.

That said, even though it’s largely an apolitical film, even though the act of making the film in Gaza itself is something of a political statement. It

has created some criticism for only appearing to advance that the story of ordinary Gazans. But, of course, that’s all we ever set out to do. We never

set out to make (INAUDIBLE). We simply wanted to portraiture these people and yet, they do not — they raise heckles of many people far and wide.

AMANPOUR: Well, Brendan, you must have known going in that anything about Gaza or the Palestinians and Israel is inevitably viewed through a

political lens. You’ve had that, you lived that through Northern Ireland, anything there — I remember reporting there was viewed through a political

lens, even when we tried just to talk about ordinary civilians.

So, as we speak and as that normalization ceremony was happening in the White House, Israel reported that there was some rocket fire out of Gaza

towards some of the towns, like Ashkelon and Ashdod, I think, right near the Gaza border. They say that two people are being treated for injuries.

Fortunately, no fatalities.

You did not report on Hamas. You did not talk to Hamas nor did you talk to Israeli officials outside, nor did you, you know, talk about Israel’s

actions inside Gaza. I guess, again, tell me how difficult it is just to tell an ordinary story about a situation that is so wrapped up in politics

and violence and has been going on like this for decades. It just seems that nobody — well, many people, yes, but some people don’t want to see

that there are ordinary kids, you know, below the surface.

BYRNE: Yes, I mean, partly, Christiane, I can’t answer that question. I’ll do my best. Except to say that we did feature some imagery of Hamas. We

shot at a Hamas rally. We saw a number of scenes where there were various motor kids were traveling around and other smaller armed groups. So, we

didn’t shy away, we didn’t embed ourselves with those. We weren’t fortunate enough, and I use the word, hopefully not incorrectly, but we didn’t manage

to capture through appearing in five years of filming, albeit sporadically, any Hamas rocket fire into Israel. And if we had, we would have included it

in the film.

But we simply decided to make a film about ordinary Gazans rather than to become (INAUDIBLE), rather than either to become a history lesson and to

start point scoring. So, we felt that, you know, there is a poverty at the bit around Gaza, around the Palestinian and Israeli issue. I think there’s

not a poverty at the political debate around, but that political debate rarely takes into any meaningful and real account the lives of ordinary

Gazans who at the end of the day are essentially locked on a tiny land mass.

And once people — and you know, it’s great to see progress of sorts in the Middle East and lovely ceremonies in the White House, but, you know, that’s

not helping to end the blockade in Gaza. You know, it’s terrible what Hamas do and they’re oppressing their own people. But, you know, it’s not simply

just able to continue for much longer, for this prison cell to continue to be operating, and these people deserve a future like ourselves surely, even

on a basic humanitarian level.

AMANPOUR: So, let me play a little clip. It’s one of the 14-year-old boys, one of the boys who was playing around in the sea we just saw in some of

that video. And he’s talking about how his family had such a — you know, his dad has three wives and he’s got 10 siblings from just his own mother

and then many else. He’s talking about how crowded his conditions are and his love of the sea.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): I live in the Der Al-Balah refugee camp. My entire family lives in one house with only three rooms. There’s

hardly enough room for all of us. Sometimes us boys sleep by the sea to escape the overcrowding. I feel much more comfortable when I sleep on the

beach. I was born by the sea. I live by the sea and I will die by the sea.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: You use a lot of imagery of kids and others looking out into the big — you know, the big empty, so to speak, looking out over the sea. If

you were to sum up in our last 30 seconds, how would you say the people who you profiled felt about life?

BYRNE: They really have a strong human spirit, and they really have a sense that, you know, one day soon, hopefully for the youngest of them,

their lives will change. And the sea is really important and I’m glad you picked up on it because it’s the most beautiful color of blue, but it’s the

most unusual set of prison bars imaginable.

And so, the juxtaposition of that imagery of the sea and how it helps the ordinary Gazans breathe on a daily basis, but yet at the end of the day, it

is still a long prison wall because of the boats that flock the harbor. It is difficult on many occasions to keep a sense of hope in the face of such

adversity. But a deep down at most basic human level, the characters we feature and generally Gazans in general have a portion of hope for the

future, but they want to see that hope hopefully come to fruition.

AMANPOUR: Well, you know, peace came to Northern Ireland in the end. Let’s hope it comes to Israel and the Palestinians. Brendan Byrne, thank you so

much, indeed.

Now, in a normal year, the United Nations would be marking and celebrating the progress made on many of its development goals like poverty, hunger,

education and gender equity, a lot of which are at stake in Gaza. But this year with COVID, there is no progress at all. In fact, it is worse than

that. The numbers are going backwards.

Philanthropist Melinda Gates, as leader of the Goalkeepers Initiative, is sounding the alarm on what the Gates Foundation calls “mutually

exacerbating catastrophes” that are not unfolding before our eyes under the COVID pandemic. And I’ve been talking to her about the global response to

this pandemic.

Melinda gates, welcome to the program.

MELINDA GATES, CO-FOUNDER, BILL AND MELINDA GATES FOUNDATION: Thanks for having me.

AMANPOUR: So, every year your foundation puts out its report, the Goalkeepers report, and you measure and track some of the goals including

those that are the U.N. sustainable goals. And for the first time, and let me read it because it’s quite stark, your report says, we have now to

confront the current reality with candor. This progress we’d be making has now stopped. This year, on the vast majority, we have regressed.

Wow. That is a really sobering conclusion. What are the main areas of regression, the most important areas, in your mind?

GATES: Yes. Well, we thought it was important to put out the realism of what’s happening in the world with COVID-19, and one of the biggest places

that it’s noticeable is the drop in poverty. After 20 years of gains on extreme poverty, we now have another over 35 million people dropping

backwards into extreme poverty, which means they live on less than $1.90 a day, that is unbelievable.

AMANPOUR: I mean, it really is. What does it mean going forward?

GATES: Well, it means that we’re going to have a lot of building back to do, a lot. Because whenever you get a pandemic like this, and we know it

from Ebola, you get these shadow pandemics. So, for instance, women don’t go into clinic to deliver their baby because they’re afraid to. It may not

be safe. And so, we have to look at what are other ways to reach people.

So, for instance, Ethiopia said, okay, we know women aren’t going to come into clinic, even though they should, to deliver their babies. How do we

get out clean health birth kits to traditional midwives for the women who are delivering in their homes? We have to think creatively and innovatively

about every single category of health as we think about how do we invest and make the right investments on behalf of people.

AMANPOUR: Well, let me just read from your reports and what’s known statistically, that COVID does disproportionately impact women on jobs.

They are 1.8 times more likely to lose their jobs in a recession like this. On health care, you’ve talked about being turned away from hospitals and

not going to clinics. On violence, you warned of a shadow pandemic against women raging behind closed doors. On education, some areas with online

learning don’t accept girls having phones, et cetera.

The Malala Fund estimates an additional 20 million secondary school age girls could remain out of school after this crisis past. That’s after the

crisis past. That’s — how many years does it take to recoup the kind of losses that you’re seeing and the world seeing right now?

GATES: It’s going to take us probably decades. Probably one decade, and in some areas, two, to regain back. You know, when you see these kinds of

losses and these kinds of setbacks, you say, oh, my gosh, we know when this has taken before. Now, what we have to do is be more innovative, more

ingenious. We didn’t have the mobile phone as a tool 20 years ago. Now, we have it as a tool, and you’re seeing communities start to use it very, very

creatively.

We know, for instance, in Kenya, radio — 100 percent of the population in Kenya knows about COVID-19. And that’s because the Kenyan government used

radio to get all these messages out about COVID and how to take care of yourself.

Now they’re moving on and using broadcasting, that is, TV, to actually start to do educational classes on TV. So, we need to use all of these

opportunities, and technology is one area that gives us some opportunities to start to say when, as we build back, how do we absolutely use those

tools to accelerate the progress?

AMANPOUR: But we all know, because it’s been the story of the pandemic, that the traditional way of dealing with a global crisis, i.e., to gather a

coalition of the willing and able to help mitigate, simply hasn’t happened.

The American leadership hasn’t been there and it just hasn’t happened, and I think your report says, basically, there no such thing as a national

solution to a global crisis.

Do you have any expectation and hope that, finally, this somehow will happen, in order to quell the disease, first and foremost?

GATES: Well, I think what people need to understand is that there is global cooperation when you look at most of the G20 countries.

So, Europeans have come together with WHO, with countries from the south, and created this ACT-Accelerator. But the U.S. is missing from the table,

and that is a tragedy for the world. And one of the things we know is that, for instance, if the first set of vaccine dosages, the first two billion

doses, there is good modeling that says, if they only go to rich world countries, you are going to have twice as much death around the world.

So, the U.S. needs to be at that table, and it’s not right now, and that is a tragedy for everybody.

AMANPOUR: What do you think it will mean if the U.S. is not at the table in terms of who will get the vaccine, when and if?

GATES: It means we are going to see far more death around the world, twice as much death, because, when a vaccine is available, who should it go to

first? It should go to the health care workers all over the world first.

And so that is, yes, in the U.S. and Europe, but it’s health care workers in all these countries in Africa and in India, because they’re the ones who

take care of us and take care of everyone else.

And think about it; 70 percent of health care workers are also women. So, having the U.S. not at the table, not participating, not adding money for

the rest of the world and helping with this plan for equitable distribution means we’re going to see more death and disability all over the world. And

that is really a tragedy.

AMANPOUR: I wonder how worried you are about these staggering statistics that we’re seeing of such small percentages, relatively, of people in the

most developed parts of the world, the United States, even Europe, saying that they would be willing to take a vaccine when and if one is actually

delivered any time soon?

GATES: It’s incredibly disappointing, because what we’re seeing is 25 years of gains in vaccinations has been erased in 25 weeks.

The drop in vaccination rates is profound. Moms and dads all over the world tell me, when I see them standing in line at the health clinic, and I say,

why are you here, they say, for vaccines for my children. And you ask them how far — what they did to get there. They rode a bus. They walked 15

kilometers. Vaccines save lives.

And so we have to get through this time of disinformation. We will have, at some point, a safe and efficacious vaccine. And I think, once it starts to

be delivered and people start to see other people taking it and being able to back on with their normal daily life, then you will see the vaccination

rate start to rise again.

But it’s terrible what’s gone on.

AMANPOUR: What happens — and it’s all about modeling, I guess — what happens — you talked about the truth. It’s important to get the truth out

there.

When the president of the United States, as we now know from the Bob Woodward book, admits to Bob Woodward that this is a deadly pandemic, that

it’s airborne, all of that stuff, but, in public, says that it’s a miracle, it will go away, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, and as — himself, he’s

doubled down on that.

He says, yes, of course I played it down. I don’t want to cause panic.

What does that lack of transparency or that — what does that do, do you think, to the public, who are looking for answers?

GATES: Well, I think we have gotten our answer in public. We know there has been a complete lack of leadership.

We know that there is not a national testing and contact tracing plan. And you can look at the deaths in the United States, and you can say, the

reason those numbers are as high as they are, particularly percentage-wise, compared to other countries, is because of that lack of leadership.

We know families make good decisions with facts and with the right information. And the United States deserves to have leadership that is

honest with the American people. And that is not what we have had, and it’s caused more illness and it’s caused more death in our own country.

AMANPOUR: Melinda Gates, thank you so much for joining us.

GATES: Thanks for having me, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: We’re really at a turning point.

And now, of course, to America’s reckoning with racial injustice.

Dr. Eddie Glaude Jr. is the chair of Department of African-American Studies at Princeton University. His latest book, “Begin Again: James Baldwin’s

America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own,” analyzes the current moment in the context of one of America’s greatest writers. It asks what we can learn

from Baldwin’s own struggle.

And he tells our Walter Isaacson why America must confront the lies it tells itself about being — quote — “a redeemer nation.”

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thanks, Christiane.

And, Professor Eddie Glaude, welcome to the show.

EDDIE GLAUDE JR., CHAIR, AFRICAN-AMERICAN STUDIES DEPARTMENT, PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: It’s my pleasure.

ISAACSON: This book is incredibly timely on James Baldwin.

And when you started it, you probably did not know how timely it was going to be. Why did you undertake this project?

GLAUDE: Well, in some ways, I had to deal with my own despair and disillusionment.

I had — I didn’t believe the country would choose Donald Trump. And then I watched it happen. And then I watched the hyperpartisanship evidence itself

in very specific ways and how the ugliness of race and racism were beginning to overwhelm.

I had to find resources, Walter, for myself to how to pick up the pieces and begin again, because it looked as if, at least as I sat down to write

the book two years ago, as if the company was doing it again, that it was turning its back on the possibility of being otherwise.

And I had to find some resources, and Jimmy was that resource.

ISAACSON: Baldwin talks about the temptation of despair, which is what you just raised. How did it help you to prevent yourself from freefalling into

despair?

GLAUDE: Well, you know, actually, at one point, he described his despair as elegant despair, elegant despair, that you have to turn to the reality

of those you love, the future that you hope for, that you pray for, and you have to figure out a way to replenish, to find the resources in yourself to

begin again.

And so it was kind of rummaging through what he calls his — the ruins, rummaging through his writing, that I was able to find resources, to put

pen to pad, and to write my way out of a kind of despair. So, it was the work, actually. It sounds Carlylean, doesn’t it? It sounds too much…

ISAACSON: But it also sounds difficult.

I mean, it sounds like a — he writes of the messiness of our exterior lives reflects the messiness of our interior lives. Was it difficult for

you to have to dig into your own emotional life?

GLAUDE: Absolutely.

Oh, Baldwin is an exacting companion. He forced me to confront the scaffolding of my own life, as a precondition to say anything about the

country. And so I found myself, as I was writing, reaching for my favorite drink, Jameson, over and over and over again, right?

And as I was confronting the fact that I’m this vulnerable little boy that — who grew up on the coast of Mississippi, who is constantly struggling

with his father, even as our relationship has grown into something much more beautiful, I had to grapple with that beginning.

And as I started to do it, Walter, the sentences started to jump a bit more. I became freer and more willing to take risks, because I was actually

being truthful with myself, which freed me up to be even more truthful about the country.

ISAACSON: You talk about “No Name in the Street” being a lynchpin in the book, and that was written by Baldwin in reaction to the civil rights

movement of the 60s and the fizzling or burning out of it, as a sort of second moral awakening that happened after Reconstruction, but then it

ends.

It’s been 50 years since that book. Are we due for another moral reawakening?

GLAUDE: It seems we’re right there.

And at every moment that there is a kind of reckoning with the contradiction at the heart of this fragile experiment, there is a

reassertion of the lie.

And we’re experiencing that right now. You think about President Trump’s speech at the Republican National Convention and the way in which he

narrates history at the end of that speech, virginal lands.

It’s as if no contradiction was present in our beginnings. There was this kind of redeemer nation logic that drives, right, the way in he imagines

our past.

And then you see the memos from the Office of Management and Budget saying no training around racial bias, banning critical race theory, because this

is un-American propaganda.

So, to confront our contradictions, to confront how those contradictions reside in us, for those folks, represent a kind of anti-American gesture.

So it seems that we’re right there. The ugliness — we’re on this racial hamster wheel, as we have always been since the beginning. And now we have

to figure out what we’re going to do.

ISAACSON: You say that underlying it all is what you just called the lie. What is the lie?

GLAUDE: Well, the lie is this belief that we’re the shining city on the hill, the redeemer nation, an example of democracy achieved.

And we tell the lie in order to hide and obscure what we have actually done. Baldwin writes, in 1964, in this essay entitled “The White Problem,”

he says, there’s a fatal flaw at the beginning of the country. And I’m paraphrasing here.

He says, there’s a fatal flaw at the beginning of the country, because these Christians who decided they were going to build a democracy also

decided to have slaves. And in order to justify the role of these chattel, they had to say that they were not human being, because, if they were not

human beings, then no crime would have been committed.

And then Baldwin writes this line, which is at the heart of the book. That lie is at the heart of our present problem. So, the lie we have told about

black people and their capacity, the lie we have told about white people and their superiority, the lies we tell about what we have done in the name

of that superiority, all of that, in some ways, is the scaffolding that protects our supposed innocence.

And as Baldwin says in “The Fire Next Time,” the innocence is the crime, right? The innocence is the crime.

ISAACSON: How fundamental is the lie to Trumpism?

GLAUDE: Oh, it’s at its heart.

And, Walter, you’re a child of the South. You’re a son of the South, and you’re a son of American history as well. And in those moments when the

country is on the precipice of change, when a way of life is unraveling, violence is always on its on its heels.

You think about the end of Reconstruction and the assertion of redemption and the Lost Cause, you think about the end of Jim Crow. And each of these

moments represent kind of spikes in that horrid ritual, American ritual of lynching.

So, here we have the desperation of Trumpism in some way as a kind of death rattle, I hope, of a way of imagining the country, that this is the last

gasp of a certain kind of understanding of whiteness as overdetermining, right, our democratic value and commitment — commitments.

So, lie is at the heart of it, it seems to me.

ISAACSON: Baldwin, after he wrote “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” wrote “Giovanni’s Room” about being gay, being part of queer culture in America.

How important was that to him? And would he be somewhat surprised that — the advances made in being — the civil rights of being gay and being

called a queer culture vs. the advances being made because of civil rights and being black?

GLAUDE: Yes.

To follow up “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and “Notes of a Native Son” with “Giovanni’s Room” in the 1950s is an extraordinary act of courage. And

Baldwin said he had to tell you — he said, you can’t hold that over my head. I told you.

So, it’s a beautiful moment. And when I interviewed Angela Davis for the book, she said, in so many ways, he was out there all by himself. But, at

the same time, Baldwin’s sexuality, you know, you love who you love.

Love is an extraordinary experience that unsettles, that deepens, that widens your sense of yourself and the world. And you love who you love,

whether it’s a man or a woman. And Baldwin wanted to open up that space, right? But he also didn’t want us to get trapped in the categories.

So, what did it mean to be gay or queer or straight or — so, these categories can, in some ways, lock you in and constrain you. They could

spring the trap.

So, in the last interviews published with Quincy Troupe, there is one fellow who is trying to interview him and trying to lock him into a certain

understanding about the gay liberation movement, and Baldwin is deconstructing the category.

Or when you read “Male Prison,” or his last essay, “Freaks,” there is a sense in which he’s trying to destabilize these categories in order to

release us into a certain way of being.

But then there’s the exchange, Walter, with Audre Lorde. And Audre Lorde rakes — I mean, takes him to the shed around kind of the patriarchal

underpinnings of the understanding of gayness, right?

So it’s a complex subject matter to kind of unpack. But I think he would be interested in what we are experiencing today. But he would also be cautious

about how we understand the nature of freedom that is being expressed today, if that makes sense.

ISAACSON: You talk about him resisting being locked into categorizations. Being locked into the categorization of being black, to what extent did he

see that as a problem?

GLAUDE: Well, he was always concerned about this aspect of black power that he called this mystical blackness. He used a different word, but he

called it this mystical blackness.

And he said that it springs the trap, because Baldwin wants to insist on a certain level of individuality, right, because he wants to say, the moment

that black people start — in one essay in “Black Power,” I think, he says moment black people stop — step outside of the orbit of white people’s

expectations, we’re talking revolution.

So, this assertion, not of a kind of crude and crass individualism, but an idea of black individuality for Baldwin, becomes this kind of revolutionary

act, where we step outside of the stereotypes and we try to find our own voice by sometimes singing off-key.

But he wants to make a distinction, I think, between racism and white supremacy and black culture. Right? Racism and white supremacy is horrible.

It’s irredeemable. But it doesn’t follow from that the beauty of black cultural life has to be diminished, the way we speak, our language, our —

the way — our cuisine, the music, the culture that has been so critical to American life.

On the lower frequencies, we speak for you, as Ralph Ellison would say. He doesn’t want to give that up, but he doesn’t want us to get permanently

docked at the station by holding onto this notion of blackness that is apart from human experience.

ISAACSON: Your grandmother in Moss Hill, Mississippi, on the Gulf Coast, once said to you when you were angry about something: White people aren’t

going to change. Get that through your head.

Do you still believe that, and do you think Baldwin believed that?

GLAUDE: Let me unpack it.

When she told me when I was an undergrad at Morehouse that she was trying to keep the rage from taking root in my spirit, from dwelling on it, but,

today, I think I understand it in this way. Those people who are committed to whiteness, they’re not going to change.

But then there are people who happen to be white, whom I love dearly, who are engaging in this ongoing interrogation of how race and white supremacy

distorts and disfigures our soul.

So, when I say in the book that the idea of white America is irredeemable, what I mean is that there is nothing about the belief that white people

matter more than others that can be salvaged.

So, when you ask me the question, can white people change, I would say human beings can be changed. But those who are committed to the ideology of

whiteness, to where they can’t understand themselves otherwise, well, if they change, it’s up to them. It’s up to them, if that matters.

ISAACSON: After a lot of the moral reckonings, be it Reconstruction and the civil rights movement, and even the Obama era, there has been a

backlash and a swingback.

Now, as we’re going through the era of Trump, there are people who say, OK, can’t we just get back to an era of calm? Do you think that’s a trap or a

danger for us, if we’re just trying to restore an era of calm?

GLAUDE: Absolutely. Absolutely.

I’m thinking about Dr. King’s speech in Montgomery after the Selma march. And he says some — and I’m paraphrasing — some want us to go back to

normal, to get back to calm.

And then he starts listing what was considered normal. And he starts listing all of the horrors of the period that is being called normal. It’s

not calm when poor people are dying because they can’t put food on the table and have a decent wage. It’s not normal because police were killing

black folk before this moment.

That’s not normal. That’s not calm. It’s not calm and normal that the top 1 percent or the top one-tenth percent of the country is extracting

resources, while everyday ordinary people like my daddy, who worked his behind off as a letter carrier, busted their behinds to make ends meet,

there is nothing normal about that.

So, part of what we have to reckon with, I think, Walter, is that our democracy is broken. I think young people know this, and they’re reaching

for languages to help them imagine how to fix it.

A nostalgia for the broken — a nostalgia for what was in the past is a way of sticking one’s head in the sand, to my mind.

ISAACSON: In the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the other shootings, Breonna Taylor and the things we have seen, how do you speak to

your son about the moment we’re in?

GLAUDE: Yes.

It’s a hard conversation. And I have been having it with him since he was, like, 8 or 9, from — he’s 24, and you just think back to Trayvon and how

young he was. Tamir Rice. I remember we were in an airport when he found out that the police officer wasn’t going to be charged, and he was pacing

the airport like a caged panther.

Or, during the George Floyd moment, and he said he had to go protest in Trenton. And I was like, but COVID, COVID-19. Are you going to — and I

played the mama card. You going to jeopardize your mother? And he said: I got to. I have to.

So, the conversations are hard, but he’s teaching me now. He’s teaching me what it means to exhibit courage and imagination in this moment. The one

thing that I have been trying to do over all of these years, Walter, is to impart to my child the lesson that Baldwin imparted to do me.

Whatever you do, how angry you are, how rageful you feel, don’t let hatred take root in your spirit. There is nothing good that could come of it. And

so he’s acting, but not from a space of hate, but for a love of justice. So, I’m the student now these days.

ISAACSON: What would Baldwin have us do now?

GLAUDE: You know, I don’t want to exhibit a kind of hubris to anticipate his words.

There are 7,000 pages of his words that we can return to. The one thing that I think I have learned from all of these years working and writing and

walking with Baldwin in my head is that we have to tell the truth, as much as we can bear and then a little more.

We have to bear witness, which means we have to make the suffering real for those who willfully ignore it. So, tell the truth, bear witness, and create

the conditions for us to imagine ourselves otherwise.

ISAACSON: Professor Eddie Glaude, my friend, thank you so very much.

GLAUDE: Thank you, Walter. I appreciate you.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And, finally, as we commemorate 80 years since the Battle of Britain, we take this opportunity to honor veterans across the world.

In fact, America’s oldest World War II veteran, Lawrence Brooks, turned 111 this weekend. The celebrations paid homage to the serviceman’s time in the

predominantly African-American 91st Engineer Battalion.

The National World War II Museum held a socially distanced event outside his house in New Orleans. It featured a performance from the Victory

Belles, a military flyover, and a very special cake.

And that is it for our program tonight. Remember, you can follow me and the show on Twitter. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.

END