Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: November 8th at 7:30 in the morning, this town started to burn down, within 3 hours it was gone.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Paradise found. As fires rage across California, Oscar-winning director, Ron Howard, shows us what happened to the people left behind.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DON CHEADLE, ACTOR, “HOTEL RWANDA”: I cannot leave this people today.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: — a shocking twist for the real-life hero the world knows from “Hotel Rwanda.” Why he’s now under arrest in his own home country.

Plus —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JAIME CASAP, FORMER EDUCATION EVANGELIST, GOOGLE: What I’m hoping that happens through this process is that all of a sudden, we see education as

one of the most important priorities we can focus on.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Google’s education evangelist tells Ana Cabrera how schools can adapt to the pandemic.

And finally, “Look at Me.” How Iranian-American photographer, Firooz Zahedi, got from there to here and help define an era.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

For weeks the skies over California have looked like this, an alternative universe. The wildfire blazes bleeding into the heavens. Dozens have raged

through California, Washington and Oregon scorching millions of hectares of land killing residents and destroying homes, and climate change is the

gasoline pouring all over these tinder boxes.

This same horror show has played across the world, in Australia, the Amazon Rain Forest and even in the Artic Circle as extreme weather becomes ever

more so. But what happens to people after the ashes settle? That is the focus of prolific director, Ron Howard’s latest documentary, “Rebuilding

Paradise,” which follows the aftermath of the 2018 campfire there that killed 85 people. Here’s a clip from the trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: The state’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire in history. The Town of Paradise is basically ash.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I lost my house, too. I tell you what, it’s not easy.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: No, it’s not, but we’re alive.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: It’s not just that I lost my house, it’s not that I lost my memories. My entire way of life is completely gone.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: As hard as it is to say, I don’t see the town coming back.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Ron Howard, welcome back to the program.

RON HOWARD, DIRECTOR, “REBUILDING PARADISE”: Thank you. Good to be back.

AMANPOUR: Well, I don’t know whether you knew it was going to be in the news again, but here’s your new documentary on the fire in Paradise,

California. What made you actually want to do this film on that fire?

HOWARD: I knew Paradise. My mother-in-law had lived there the last four years or so of her life. I had been there many times. I knew what kind of a

town it was. You know, it’s not a tourist destination, not an industrial center in any way, shape or form, not even logging anymore. It’s a place

where people wanted to be because they just loved it there, and they wanted to raise their families there.

And, you know, like a lot of things, Christiane, we all see these images. They’re horrifying. We feel empathy, we do what we can about it, or we

don’t and move on, but we move on. And in this case, of course, because it was personal to me, you know, my thoughts went deeper. And I turned to our

team and said, is this a story to cover? What’s going to happen when the news cameras leave?

AMANPOUR: So, it has that personal gut punch for you, that personal relevance. But let’s just remind people of the facts and figures. I think

it’s something like 150,000 acres were burned, almost all, 95 percent of all the structures, houses, whatever other structures were in that town

were burned, and about 85 people lost their lives in this fire.

You also, though, you know, from the very beginning, you have all these people talking about what it was like to nearly die in this raging fire,

and yet, you also have them coming back, or at least a certain number of people coming back wanting to rebuild. I’m going to play a little clip to

illustrate that.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I got a Paradise permit to build my home at 1552 (INAUDIBLE) Road. I’m jazzed. Awesome, man. Awesome. Was sick. Yes. We’re

on now. This is the beginning.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: It’s exciting.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes. I guess it finally caught up with me. Yes, it’s a big deal.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: It is a big deal. Very big.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, it’s a big deal. New home. New beginning.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, it’s obviously really emotional. They’ve had a near-death experience, but it’s also that American thing that makes people want to

rebuild, to stay, and the eternal optimism. What struck you most about the people there?

HOWARD: Of course, I knew the people well or not personally, but a sense of who they were. Yes, they are this kind of rugged individualists. That’s

that brand of thinking and that is that kind of, you know, Americanism there. So, it was particularly devastating, of course, when their entire

world is ripped out from under them.

You know, the definition of, you know, what a productive day is completely changes, and they’re very — you know, they are people full of pride, as

are most people most places. I think, you know, it does beg the question, and I think for them in many instances raise the question, what should we

really expect, you know, from our government? What should we expect from government agencies? What kind of help is there for us? There was a sense,

from people who had been on the fire safety committees and so forth, that they had done some of what they could do to try to prevent this kind of

catastrophe, but not all they could do.

AMANPOUR: Right.

HOWARD: It couldn’t get all of the ordinances through and so forth. And so, there was also a sense of regret for many people that only intensified

sort of the PTSD they were all experiencing.

AMANPOUR: It raises this question about what should we expect from our government? Many people, the majority of the world, actually, who believes

in the catastrophic, cataclysmic advance of climate change believes the government should be doing more all over the world, but particularly in the

United States. You seem to have shied away or deliberately stayed away in this film from making climate change political points.

You do have a slightly — a tiny little clip of President Trump, who was there, confuse the name Paradise, called it Pleasure. So, you put that in,

but you usually stay away, don’t you, from the climate change aspect of it?

HOWARD: Well, I didn’t view it as a polemic. To me it was sort of a case study and what does it mean afterward? Let’s not politicize why it

happened, that’s not really for this film. I was interested — because many people in the town believe different things. Not what it was about to me.

It’s certainly a factor, you know, and the science say it, and we say it, but so is the forest management, which we also spend some time talking

about as well.

In this case, PG&E caused it, they were culpable, they admitted it. In other instances, the horrible fires now are caused by, you know, either

fireworks and lightning strikes and other things. So, the point is, these catastrophes are happening all around the world, and what does it mean to

the individual? I was trying to build sort of a pathway to some empathy for audiences who hadn’t really thought about it before.

AMANPOUR: So, to that end, and you are a filmmaker, let’s not forget, you sort of have a little bit of a happy ending solution to this documentary.

We showed the gentleman who was getting the permit to rebuild his house, but also you go to a school, you see a new group of graduates. Let’s just

play this clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: The fact that we are here tonight to celebrate this milestone is a miracle. Because you survived one of the most destructive

wildfires in our nation’s history. It left us a different people. You are the first generation of Paradise High School graduates to rise from the

ashes of what life was, to take a bold step forward into a new and uncertain future. But with what you’ve been through, you have what it takes

to persevere. Congratulations and good luck.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, you know, I guess it’s your traditional commencement fare, you know, inspiring and invigorating. But he also says, you know, an

uncertain future. You’ve been through such a unique experience. Right now, we’re seeing the biggest fire in California history raging. It’s been

raging since the beginning of September. Most of the most deadly fires have happened in California, you know, in the last decade. What do the people

who you profiled say about their future? Not just those graduates, but have people seen the film?

HOWARD: Yes, they have seen the film, and the response has been very positive. I think they felt the process of participating in the film, and

I’m grateful in seeing the film to be cathartic and, you know, representative. Look, the town is much smaller than it was. It’s going to

be a long time before it’s 26,000 people again. I think it’s, you know, maybe 4,000 now.

Coronavirus has not been particularly devastating for them, but, of course, it’s a huge factor, and they were packing their things to get out of there

10 days or two weeks ago when one of the fires once again threatened the area. It turned and spared them this time. There is a lot of uncertainty.

Some of people that we followed, you know, made it pretty clear they weren’t going to stay.

I found a couple of things that were interesting to me. The people who did want to stay and were committed, they were the ones that kept showing up at

the functions. You know, whether it was a town meeting, whether it was the community memorial service or the Christmas tree lighting ceremony or their

parade at Gold Nugget Day commemorating sort of the history of their town founding and so forth, those people who kept showing up also became the

problem solvers in many ways, the ones who did have a shared vision of what they wanted.

They weren’t always politically on the same wavelength, but they did put that aside, you know, and they kind of beat city hall. I mean, they managed

to find solutions, and it was often a struggle. And I felt like in a lot of ways, they were showing us what problem-solving can look like when people,

you know, decide to come together in the middle and make something happen, something that they believe in. So, I do think there is a note of optimism

in that, because those people are achieving, you know, kind of what their new dream is.

AMANPOUR: I think — I mean, to me it sounds like you’re describing community, the notion of community, and certainly that has taken a

battering in the United States and many other parts of the world as well, but certainly in the United States.

COVID, we’re now past 200,000 deaths, the biggest death toll in the world, and I know — I believe your wife and maybe your daughter as well

contracted COVID during the height of the virus. You were in lockdown but in proximity. I was touched by the fact that you stayed close to your wife,

and you describe once she started to get better, you taking socially distant strolls that you describe as sort of Victorian era courtship

strolls. Tell me what was that?

HOWARD: Well, I was coming back from location where we had just finished filming “Hillbilly Elegy” in Atlanta, and it was — you know, that all

productions were stopped the night we were shooting. I came back. She, you know, had the fever and was having some of the symptoms but was not in

horrible distress, thankfully, so I was staying in kind of my editing room that I have there in town. And I would — yes, I just would show up and it

was just great — you know, it was great to see her.

The first time when I came home, we didn’t even do that, it was late in the day, and I just — all we could do is sort of talk to each other through,

you know, the glass door. And it was like a movie, you know, holding our hands up and all the corny — all the tropes of what you might imagine. But

it was really emotional. Thank God, you know, she navigated it well.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you, I’m sure you are fed up with being asked this, but you have been around for so long as a child actor, you know, then movie

director and everything, a documentary filmmaker. I mean, I was in Iran growing up when I watched you as Opie on “The Andy Griffith Show” And then

I was in boarding school when “Happy Days” was about one of the only things we were allowed to watch. And I loved it.

HOWARD: I had no idea that ultra-Americana show “Andy Griffith Show” traveled anywhere outside of the United States.

AMANPOUR: Oh, yes.

HOWARD: So, that’s amazing.

AMANPOUR: Definitely to prerevolutionary Iran. But — so, let me ask you. You know, you have said, and I’m interested in this, that there was a time

when you felt a little bit threatened by being asked that all the time, that people put all that attention on you. But in recent years you said,

I’ve come to appreciate my unique place in pop culture. You know, I think that’s a very frank statement and it’s a very accurate statement.

I just want you to reflect for us, what do you think your place has been, and what has your massively long career contributed, which is a lot?

HOWARD: Well, I always wanted, you know, my adult career to be as a storyteller, as a filmmaker, director and a producer. I’m partnered with

Brian Grazer at Imagine Entertainment. We make all kinds of shows for all mediums. And it’s a thrill to be around that, and that’s really something

that I’ve always wanted. And I always felt like that there — you know, earlier in my life there was kind of this — you know, both “Happy Days”

and “The Andy Griffith Show,” my earlier work, by referencing it, you know, was it creating a kind of limitation in people’s minds as to what my

capabilities, creative capabilities, might be and my capacity to do interesting work, you know, beyond those shows.

Well, as I’ve been able to do that work and build Imagine and make projects that I’m proud of that are ambitious and travel the world making them, you

know, I’ve just been able to realize that I — hey, I achieved what I wanted, and I probably wouldn’t have without that background. So, it’s not

a limitation, it was an asset. It’s something that I can really cherish. And now, with many people, I have this kind of, you know, decades-long

relationship that I now really value.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

HOWARD: Interestingly, when I was doing the “Beatles Eight Days a Week” documentary and I was — we didn’t get this on camera, but when we were

doing press, I had a similar conversation with Paul McCartney about this. We were walking from one press conference to another, and I said, well, you

really brought so much through your interviews, I really appreciate it. And he said, it’s only been in the last couple years that I really felt relaxed

talking about the Beatles, because I was always looking forward, and now, I feel like I can savor, you know, what we’ve accomplished. And so, that

resonated with me as well.

AMANPOUR: That’s a great reflection, actually. And lest we, you know, be remiss in saying there has never been a successful child actor such as

yourself who has progressed to be such a mogul. That’s what’s being written about you and that’s true. You occupy a unique place in the pantheon.

I want to ask you finally, because obviously we’re in the midst of a whole new racial reckoning, and you’ve seen obviously the new Hollywood diversity

standards, you’ve seen what Broadway stars and Broadway writers and theater teams want to recreate there to make it more representative. You know, you

won best director for “A Beautiful Mind.” Do you think you could have won it under today’s new representative demands, and do you think this is going

to work, more to the point?

HOWARD: Well, that project probably wouldn’t have qualified, you’re right. And I don’t know the details. It’s possible I could work on a project then

they could say, well, you don’t actually qualify. But I don’t think that would be the case, because I do — again, in my heart, I really support the

spirit of what they’re trying to do, and I also think audiences are beginning to expect it, and I that think we are, in our own way, a kind of

a service business.

We have to speak to our audiences in ways that resonate for them. But I think you’re right, I doubt if “A Beautiful Mind” would have met that

criteria. But I really hope that in a very organic way that all my projects, in recent years and going forward, would meet that criteria.

AMANPOUR: Well, that’s great to hear from you. Ron Howard, thank you so much for joining us.

HOWARD: Always a pleasure. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Such an impressive body of work. Now, Ron Howard did not make this movie, but “Hotel Rwanda” did inspire people trying to make sense of

the heroes and villains during that nation’s terrible 1994 genocide.

Paul Rusesabagina became an international icon for his work saving more than 1,200 people who were trapped in his hotel there. While machete

wielding marauders stormed around outside. In all, nearly a million people were killed in 100 days.

In 2004, Paul’s story won Oscar nominations. And in 2005, he was awarded the medal of freedom, America’s highest civilian honor. It all seemed like

your typical Hollywood happy ending. But earlier this month, the whole story turned upside down. Suddenly, he’s arrested and charged with

terrorism. He was in court again in Kigali, Rwanda today seeking bail.

And joining me to understand this reversal of fortune is journalist and author, Anjan Sundaram, who has written extensively about the authoritarian

political climate in Rwanda since the genocide.

Welcome to the program.

Can you — this is an extraordinary story. Essentially, his family is claiming that Paul was kidnapped. He left his home in Texas. He thought he

was going to neighboring Burundi to give an inspirational reconciliation speech, his experience with genocide, but that was interrupted and he was –

– whatever they call, disappeared back to Rwanda. Tell me how that happened?

ANJAN SUNDARAM, AUTHOR, “BAD NEWS: LAST JOURNALIST IN A DICTATORSHIP: Yes. So, I mean, there have been conflicting accounts of what exactly happened

Paul, but the Union Rights organizations that I follow seem to indicate that Paul was forcibly extradited or kidnapped to Rwanda from Dubai, he was

on route to Rwanda in Dubai, and six hours after he arrived in Dubai, he was bundled into a plane, and by his own account, he woke up in Rwanda.

AMANPOUR: Let me just play this little clip. It is actually Paul inside the Kigali prison system and court system, giving an interview to the “New

York Times” but he was surrounded by, you know, the law and order officials in Rwanda. Let’s just listen to this clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PAUL RUSESABAGINA: When I arrived in Dubai, there’s someone from Burundi who was — who had hired a private jet, and that private jet was supposed

to take us from Dubai to Bujumbura. It took us from Dubai to Kigali. Well, I was taken somewhere, I do not know where. I was tied. My legs, my hands,

my face. I could not see anything. I don’t know where I was. Yes, after those three days I have been treated very, very well. Yes. I’m not

complaining of anything.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, that’s interesting. He gives a dramatic account of what happened, and then he says, I’m being treated very well, I’m not

complaining about anything. We understand that he was — you know, obviously there were government officials sitting in on that interview.

What have you been able to learn? Any more about his treatment?

SUNDARAM: I think one should look at this trial not expecting any justice from it, but rather seeing it as a show of force, Kagame’s — show of power

by Kagame. And I would look back to the arrest and death of the singer, Kizito Mihigo, earlier this year. Kizito won the Havel Prize this year for

creative dissent and he was found dead in the Rwandan prison cell.

But shortly after he sang about killings that Kagame had conducted, he was accused of terrorism, evidence was produced that can’t be challenged or

verified in any open or transparent way, and he was produced much like Rusesabagina was in front of police officers and he began to incriminate

himself. It became a farcical (ph) theater. And I would imagine some similar theater would be forced upon Mr. Rusesabagina in Rwanda simply so

he stays alive.

AMANPOUR: OK. Let us just say, in fact, what the government is saying. They have charged him with some 13 counts of terrorism, and they are saying

that it’s because of the movements that he started, MRCD, which is a coalition of groups opposed to the government, but they say a movement

called FLN, or the National Liberation Forces, is a militia and that he is, you know, in charge of that.

This is the government. Paul Rusesabagina was arrested in Kigali based on an arrest warrant issued in November 2018. He is, by his own admission, the

political leader of the National Liberation Front militia. And in 2018, attacked villages along Rwanda’s border with Burundi and killed at least

nine civilians. He will stand trial on charges that include funding an irregular armed group, murder and recruitment of child soldiers.

So, we’ve read all of this out because we actually wanted a government official and this is what we’ve got from them instead. But — OK. Here we

have a person played by Don Cheadle in the Hollywood movie “Hotel Rwanda” who, until now, there was never a chink in his story at all in his more

than, you know, 25 years since the genocide and since all that happened.

He was a hero, and he went around preaching what he learned in reconciliation. Why do you think this has happened? Why is the government

saying that he will stand trial on terrorism charges?

SUNDARAM: I think it’s happening because Paul Rusesabagina is such popular and respected figure for his courageous actions during the genocide which

makes him popular among Tutsis, among Hutus, a heroic figure in the international community, and therefore, a political threat to Kagame that

Kagame want to neutralize.

And I would emphasize that Rusesabagina and many other brave Rwandan politicians, opposition politicians have tried to engage and challenge

Kagame in a free and fair way, in a democratic way, but Kagame has taken that possibility away. He’s destroyed the democratic process. He won the

last election in Rwanda by — with 99 percent of vote. And so, it’s become very difficult for people like Rusesabagina who wish to build Rwanda with a

different vision that Rwanda that they believe would be better to challenge Kagame and enact that vision.

AMANPOUR: So, you’ve written a lot about it. You wrote a book called, I think, “Bad News.” You’ve written a lot about the political climate in

Rwanda. And we’ve seen a lot of those pictures of Paul with all those dignitaries, but you could see equal and more pictures of Paul Kagame with

dignitaries from all over the world who have praised him, who have supported him and who have funded him, because of guilt, for one thing, but

because of all the indicators that he brought to — in other areas, maybe not in political areas, but in all other indicators, raised Rwanda from the

ashes of that terrible genocide.

It is a real big dilemma for the international community. What happened, do you think, to Paul Kagame who legitimately can be praised for bringing his

nation into such a strong position in that part of the world after that genocide, but as you say, has a very, very complicated and many human

rights organizations say, a very poor record when it comes to opposition, democracy and pluralism, not to mention free expression in journalism?

SUNDARAM: I think the tragedy for Rwandans today is that they’re living now in a dictatorship, and 26 years ago, they experienced a horrific

genocide that was also perpetrated by a dictatorship. So, Rwandans today again find themselves in a situation where future violence is more likely,

and frankly, they don’t deserve that.

I think Kagame has received a lot of praise. I think what one should remember is that many dictatorships build schools and roads and hospitals.

This is not particular to Rwanda. But what unites dictatorships is their destruction of democratic institutions that ensure stability, and many

dictatorships are followed by chaos and violence, and that’s the situation Rwandans face today, because Kagame has concentrated power himself.

AMANPOUR: Clearly his family and all his friends in the human rights space and all his friends in the United States in the peace and reconciliation

space are standing up and talking for him, Paul Rusesabagina I’m talking about. His family says, he stood up to soldiers and genocidal maniacs in

1994. Today, he stands up against a repressive regime, one which kills journalists, human rights advocates and political opponents. Here’s a

little clip of what his daughter said about his situation right now.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CARINE KANIMBA, DAUGHTER OF RAUL RUSESABAGINA: Our father is a humanitarian. He’s a human rights activist. He has done everything in his

power to speak up for the voiceless, to speak up for the people are not heard and who are — who have been persecuted by this government, and he

has felt the consequences of it. The Rwandan government has gone after him for speaking up. He did not plan on going to Rwanda, which is why we stand

by the fact that he was kidnapped.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, again, it is an extraordinary story. Anjan, what do you think is going to happen to Paul?

SUNDARAM: He’s certainly not going to get a fair trial. As his daughter mentioned, Kagame has destroyed all the democratic institutions in the

country, the parliament, the free press, the judiciary. And so, what he’s going to get based on historical events would be some kind of show trial

that brings a respected and popular figure like Mr. Rusesabagina to his knees. And in doing so, Kagame is showing the world and Rwandans his power

the price people pay for criticizing him.

Many people around the world, opposition politicians, soldiers, journalists, have been found dead after criticizing Paul Kagame, have been

found even beheaded, many of them languish in prisons. And Mr. Rusesabagina being an international figure of such standing is just the latest — maybe

more dramatic example of Kagame’s reach, the fact that he was able to extraordinarily kidnap him in Dubai and bring to Rwanda when — you know, I

met Paul in the United States, and he was very careful. He knew very well the dangers that he would face him in Rwanda, and one can only hope that he

will stay alive.

AMANPOUR: Well, this story and Paul Rusesabagina’s profile is very, very high, and many people are paying a lot of attention to it.

Anjan Sundaram, thank you so much for joining me.

And now the coronavirus pandemic has thrown education around the world into chaos, and for students and teachers to adapt to new and often frustrating

ways of learning.

But our next guest says that it’s not all bad news.

Jaime Casap spent years at Google working out how technology can be used to improve our learning experiences. Nicknamed the Education Evangelist, here

he is talking to Ana Cabrera.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

ANA CABRERA: Christiane, thank you.

And, Jaime Casap, welcome to the program.

JAIME CASAP, FORMER GOOGLE EDUCATION EVANGELIST: Thank you very much for having me.

CABRERA: It’s great to have you here. Obviously, this is such a stressful time right now for students and parents and teachers and school

administrators.

And yet you say the coronavirus pandemic is the greatest thing that’s ever happened to education ever. How do you see it that way?

CASAP: Yes, I tend to exaggerate for function, right?

So, I think the education system has been doing an amazing job for a very long time, right? And it is one of those things that was set up to do a

factory model type of economy, where we needed people to follow repetitive tasks. That worked well for a very, very long time.

What’s happened since is that the world has dramatically changed. And, because the world has dramatically changed, we need to look at the

education system to make sure that that education system reflects what that new economy looks like.

And so, because of the pandemic, what we’re going to be going through is a whole bunch of new innovation, because, right now, we’re trying to take the

classroom model, where a teacher sits in the classroom or stands in the classroom in front of 30 students, and we’re trying to replicate that

online, where there’s a teacher on a video, and 30 students trying to pay attention.

And what’s going to happen is that educators and education leaders and researchers are going to realize like this doesn’t work, we’re going to

need to come up with something new. And so I think that’s what’s going to happen in the next couple months, is, you’re going to start seeing some

real new innovation in the education system.

So I think that we needed this kind of push in education, or you would have seen gradual change, but it would have happened real slowly. And the world

is moving too fast for that.

CABRERA: How do you see the first step? What needs to happen right now, because, obviously, to get from here to there is a longer process and

people are suffering right now. And the challenges are very real.

CASAP: Yes.

And, look, for those of us — I have been in the education space for about 15 years. And when we launched Google apps into the K-12, or we launched

Chromebooks, we’re still talking about schools with computer labs.

And now what we’re noticing over the last couple years is this idea that we need to have one on one, just like you have a device, and I have a device,

not just our phones, but a device where we can create things, right?

The phone is great. And kids have phones, but it’s very passive. What we need are devices in kids’ hands, so that they can create things. And so one

of the components that we need to do is to make sure that our kids, our students have access to the technology.

And those of us that have been talking about equity in education for a very long time have been screaming about equity in education. And I think now

there’s a general public recognition that we have some real issues when it comes to equity in education.

And so I think that awareness is going to lead to a lot of action.

CABRERA: The awareness is there. But there’s still the logistical challenges, one being funding, right?

CASAP: Sure. Yes.

CABRERA: That’s a huge, huge challenge. We hear from state governments that they’re looking at billions of dollars in projected budget deficits

right now, $30 billion in New York, for example, $3 billion in a place like Colorado.

And we have Congress deadlocked over another stimulus.

CASAP: Yes.

CABRERA: And so where does the money come from?

CASAP: Yes, that’s a great question.

And I think that the — that we start with the focus, right? And I think schools have always been a second thought, right? And I think, again, back

to this awareness thing, not only do we have awareness around equity issues.

I mean, I have teacher friends who are shopping in a supermarket, and people recognize her as a teacher, and they walk by her and they say, thank

you for your service, like she’s in the military, like there’s this recognition that teachers are important, that education is important, that

schools are important to our community, as opposed to as a second thought or this thing that we just took advantage of.

And so I think it starts with this idea that the education system in our community should be the central point. And so I think that what I’m hoping

will happen is that local governments, state governments, federal government and corporations that live in those communities start taking

advantage of the fact that we see education or our schools as the center point of our community, and that we start funding those schools at the

levels that we need, so that we have the right educators in place, so that we have the right technology in place, so that we have the right systems in

place.

Because everyone is starting to recognize that — how important schools are. And, look, I — money is one of those things that’s always going to be

an issue. But it really comes down to what our priorities are.

And what I’m hoping that happens through this process is that, all of a sudden, we see education as one of the most important priorities that we

can focus on. And that’s always been something that we have wanted. And I think it’s going to happen now.

CABRERA: Let’s talk about Chromebooks, because you have been part of that transformation when it comes to education.

CASAP: Sure.

CABRERA: And we are seeing a more widespread use of this kind of device.

And you launched this several years ago. You couldn’t have predicted what was going to happen now with this pandemic. Did you ever imagine the scale

in which they’d be used?

CASAP: No.

So, when I — so, I was at Google for 15 years, focused on education and trying to bring technology into education, mostly because I think it levels

the playing field. I think it’s a great equalizer when it comes to access to information. Information equals education. Having access to information

as cheaply as possible is an important element to this.

So, that was — always been my focus when I was at Google. And so the Chromebook to me was this device that could not just benefit the user. Not

only did it boot up in five seconds. Not only was it cheap. Not only was it easy to use. Not only could anyone use them.

They were great for the administrator, because, when you’re running a school, most schools are small schools. And so the tech director also

happens to be the basketball coach and the history teacher. And when you throw 2,000 machines into a school, it gets complicated very fast.

And so what I saw the potential of the Chromebook was that you could actually scale very fast. So you could have one person literally manage

120,000 Chromebooks in a school district.

And that was going to benefit all the students and all the educators, because now they had access to all the tools that are out there, because

everything that we do is now online. And so having access to all those resources, all that research, all those tools was an important element to

this.

And I think that’s what the Chromebook did.

CABRERA: We are fortunate where I live for our public school district to be able to issue Chromebooks to every student in the district in order to

make this learning remotely work during the pandemic.

However, I’m overhearing the lessons, and I too often hear the teacher having to brainstorm technology issues with the students right now, so, oh,

the audio dropped out, oh, the link isn’t working, oh, my Wi-Fi had a blip.

And so I do worry that the quality of education and learning is suffering. Is that a concern of yours?

CASAP: Yes, but I think the quality of education is suffering more because of what we’re teaching students more than the technology.

I think, again, the innovation is going to happen, right? So you have those bugs. Those things happen. Buttons aren’t the right place. Those are easy

to fix, right? Those are — you go to Zoom and you say, hey, Zoom, there’s people bombing our meetings. Oh, let’s just set up a pass code.

Those things are — those things will get fixed. Those — like bugs, those things will get fixed over time.

I’m more worried about what we’re teaching our students, right, because if what we’re teaching students are things that machines can do better, we’re

failing them. So, right, so you got 45 minutes of chemistry, 45 minutes of history, 45 minutes of math, 45 minutes of literature.

That that’s not going to cut it, right? What we need to do is really focus on those human skills that our students need. But I think about my 6-year-

old, and what the skills that I want her to have nothing to do with subject areas. It has to do with collaboration, problem solving, critical thinking,

the ability to learn, creativity.

Those are the things that our students need to know how to do, regardless of what the subject is.

CABRERA: What you’re saying is the importance of collaboration and problem solving.

CASAP: Yes.

CABRERA: And a lot of those types of things are developed in the classroom, aren’t they, with those interactions between students, the

ability for a student to ask a question of the teacher, the hands-on learning that takes place so often.

So, are you advocating remote learning in place of in-class learning? Or do you see it being a little bit of everything?

CASAP: Yes.

No, I think it’s a hybrid model, right, this combination of learning online, learning because you have a device in front of you, and then going

out and doing it. That’s just the way it’s always been, and so going out and collaborating and doing it.

And, look, you and I are having a conversation. We’re collaborating over this topic, and we’re doing it online. Would it be better if we sat in the

same place face to face and we had that? Absolutely.

But we got to — we got to deal with what we have. And this isn’t a long- term solution. This isn’t something that’s going to go on forever. But this idea of learning and then going and doing, and learning and doing, and what

we have in schools right now, what your kids and what my kids have, isn’t that, right?

I know you — we think that kids are in school collaborating, but they’re not. They’re sitting in the classroom quietly listening to someone speak

for six hours, and that’s not going to get us there.

CABRERA: So, I’m hearing you say it’s really important for students to learn how to use technology.

CASAP: Yes.

We have given this generation a pass, right? When I talk to students, I tell them that they have been lied to. We call this generation the digital

generation. We call them the Internet generation. We tell them like, you are born with technology, you just know how to do it, you’re natural at it.

And it’s not true. There’s great — Stanford has some great studies that show us that 80 percent of high school kids can’t pick out the fake story

out of four stories presented to them. Elementary school kids can’t tell you what a sponsored news site is vs. a real news site.

Like, we have to give them the skills that they need, not just how to touch buttons and how to use it, but how to access information, how to vet

information, how to make sense of information, how to know whether something’s credible or not.

And we have we failed this generation, because we have told them that they’re supposed to be good with technology, and so they don’t turn around

and ask us a lot of questions, because they — we put in our head, that wait, I’m supposed to be good at this. But I don’t know how fiber works. I

don’t know how Bluetooth works. I don’t know how the Internet works.

And so what we need to do is take a step back and really focus on helping them build the digital skills that they need.

CABRERA: Let me take it a step further, though, because, again, in order to learn, you have to be able to focus on that learning.

And again, in the time we’re in, with the pandemic, there are bigger issues. It’s not just access to technology. A report just got from UNICEF

and Save the Children found this pandemic has led to 15 percent increase in the number of children living in poverty around the world right now.

CASAP: Right.

CABRERA: And they say that represents an additional 150 million children who don’t have access, not only to education, but to housing and nutrition

and health services, sanitation, even clean water.

In fact, the CEO of Save the Children said this — quote — “This pandemic has already caused the biggest global education emergency in history. And

the increase in poverty will make it very hard for the most vulnerable children and their families to make up for the loss.”

How do you make sure those most vulnerable children and communities aren’t left behind, especially when some families are just trying to survive?

CASAP: Yes.

Look, I grew up — I’m a first-generation American. I grew up on welfare and food stamps in Hell’s Kitchen, New York, back in the ’70s and ’80s,

when it was really — when the name was deserved, right, back then. And I grew up poor. I grew up sometimes many months going by without electricity,

some days without food.

And so this is personal to me, right? This idea that people are growing up like, that kids are growing up like that anywhere in the world is something

that I feel personally.

I think that education is the key to this, right? And I think that we should focus on education. And I get that this is a terrible thing that’s

happening to us.

But what I — looking at this as a glass-half-full opportunity, the way we need to look at this is that education has to become a priority for us. It

has to become something that we focus on, because that’s the only thing, in my opinion, that helps students get out of poverty, is this idea of

learning how to do stuff, learning how to skill, learning a craft, learning things.

I mean, we have an opportunity, because we live in this world now where we have a long tail economy, where any kid can pick up a laptop and have a

great idea, and then start that idea, and launch it, and have a business running, right? That’s the world that we live in.

CABRERA: I know you focus right now in your work on equity and diversity and inclusion, in partnership with higher education institutions and school

systems.

Why do you think communities of color are disproportionately impacted, with fewer education resources and opportunities than their white counterparts?

CASAP: Well, there’s a lot of reasons. And we can go back and — we can go back to the 1800s to dive deeper into some of these reasons, the structural

— structural things that we have done in the education system.

But, right now, the main thing that we can focus on is the funding issue, right, this idea that we fund school, we fund education based on zip codes,

that, if you live in a great zip code, your school has a lot of money, but if you live in a bad zip code, your school doesn’t have a lot of money, and

it’s all based on property tax.

And that, to me, is the number one place that we can focus, because it shouldn’t be that way. We don’t find other public services like that,

right? The police department in a rich neighborhood doesn’t have better police cars than the police department in a poor neighborhood. They don’t

have bicycles, right?

Like, it doesn’t make any sense. And so I think the first thing that we can do is understand that we really have an equity issue. And what it means and

the difference — and many people think equity means equality, and that means that you have a rich school district and a poor school district, and

we should fund them the same.

That’s not equity. Equity is understanding that this poor school district is going to need a lot more resources than the rich school district,

because they’re dealing with more issues, and we need to fund those schools appropriately. We need to make sure that the best teachers are there, the

best resources are there, the best support structures are there.

And that’s what equity is.

CABRERA: Let me end on this.

What is your advice to students who are struggling with education right now?

CASAP: Yes.

So, I think — when I think about education — and, again, I always — I do a lot of presentations. And I always start with this idea that education is

what disrupts poverty.

And what I mean by education isn’t education system. I mean education, making yourself a better person, making yourself smarter. And so, for

students who are struggling with education — and I was one of those too, right? You don’t really find yourself for a very long time.

When I talk to students, this is the question. I don’t ask them what they want to be when they grow up. That question doesn’t make sense anymore.

That question is an old world question.

The question that I ask students is this: What problem do you want to solve? We’re natural problem solvers. That’s what we are as human beings.

What problem do you want to solve? And if you don’t know, spend some time thinking about the problem. It doesn’t have to be a global problem. It

doesn’t have to be climate change.

It can be how to make cars go faster, how to how to sell more widgets, whatever that is, but what’s that problem that you want to solve? And then

here’s the important question for every individual person, every individual student. How do you want to solve that problem? How do you want to take

your gifts, your talents, your passions and solve that problem?

Because there’s a million ways to solve problems and tackle problems.

And then the last question I ask students is, what do you need to learn to solve that problem? What are the knowledge, the skills and the abilities

that you have to have to solve that problem that you’re passionate about?

And here’s the magic of the whole thing, is that everything that you need to learn, every skill that you want to develop is out there. And the

Internet is a huge part of this. So, go out, determine what those knowledge skills and abilities are, and then go solve that problem in the way that

you want to solve it that you’re passionate about. And go do that.

And that, to me, is what education should be about.

CABRERA: Jaime Casap, thank you so much for your time. I appreciate the conversation.

CASAP: Thank you very much for having me.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

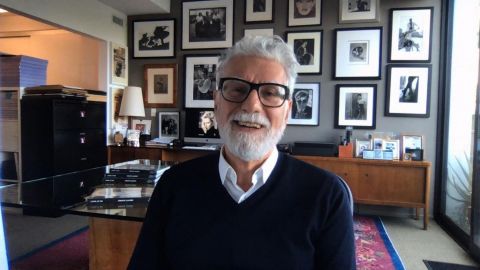

AMANPOUR: And, finally, we turn to one of Hollywood’s most celebrated photographers.

After growing up in Iran and attending boarding school in Britain, Firooz Zahedi went from the diplomatic corps to art school to Andy Warhol’s

“Interview” magazine. Along the way, he became Elizabeth Taylor’s friend and favorite photographer, and went on to capture images of all of

Hollywood’s royalty.

Zahedi is out with a collection of his best work in a new book called “Look At Me.”

And he’s joining me now from Los Angeles.

Firooz Zahedi, welcome back to the program.

FIROOZ ZAHEDI, PHOTOGRAPHER: Thanks.

AMANPOUR: I guess I want to ask you, with that big — I can see a wall of photos behind you. What took you from a pretty conservative upbringing in

Iran to Hollywood?

I want to read this quote. You said once: “Hollywood was a safe place, where people were colorful and well-dressed. They kissed each other and had

happy endings.”

And you were a little bit obsessed with it, right, as a little boy?

ZAHEDI: Well, the obsession came from the fact that, in the middle of the 20th century, Iran was going through a lot of political turmoil, and a very

conservative government.

And my family was a part of that government. So I picked up a lot of tension during the early ’50s with what was going on without really

understanding what was going on. And I just needed something to take me away from that.

And we had movies. There were cinemas. We could go to the cinema. And I would see these beautiful images, colorful, happy. And I thought, that’s

where I want to be. I had no idea what Hollywood or America, for that matter, were, but I just wanted to be there.

And as I grew up and became aware where it was, I had this thing in the back of my head, I’d like to still go there at some point. And I finally

did it.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: Well, interesting, because that brings me — and we’re going to show a few pictures of some of your iconic work and some of the great stars

who you photograph. So we will put those up as we chat.

But the book is called “Look At Me.”

And I want you to tell me why you chose that title.

ZAHEDI: For three reasons.

The first reason is, as a photographer, when you direct someone to a sitting, you give them directions as to whether they should look to the

left, to the right. And then you say, look at me, so you have eye contact.

A second reason is, when you’re working with celebrities, and shooting them for magazines or for an advertising campaign, they’re doing that in order

to promote a film, a music album, or a TV show or whatever.

So they want you to look at them too. So they’re saying, look at me.

The third reason being, my very personal and, like, look at me, I made it, you know? I had no idea I would get to this point in my life. But I did.

Somehow, I managed to get. Lucky me. Just look at me.

AMANPOUR: Well, I think that’s — it’s really interesting, that.

And you almost are a throwback to a bygone era. I mean, I’m not saying that as if you’re a dinosaur, but you worked with a camera and film, and when

magazines were jam-packed with — they were thick, the glossy magazines, “Vanity Fair,” Vogue,” all the other Hollywood magazines.

You had all these amazing jobs, so to speak.

What is the situation like now for that kind of work?

ZAHEDI: Well, it’s totally changed since the Internet came in to the picture, so to speak.

I lived through the golden age of photography for magazines, the ’80s ’90s, the early 2000s. There was a big budget. Magazines had a lot of

advertising, so they could splurge on getting good photographers, good hair and makeup people, fly people around the world to do stuff.

But they don’t have that budget anymore, because everybody’s shifted to the Internet with — for advertising purposes. Nobody buys magazines anymore.

And if you look at them, they’re very skimpy, “Maxim,” 100 pages maybe.

I’m primarily talking about magazines to do with style, fashion magazines, or magazines like “Vanity Fair.” They really don’t have that readership.

Nobody goes to a newsstand anymore and stands there looking through magazines and buying one.

Everyone just clicks on the computer and goes on the Internet. And most of the magazines have switched to having an online magazine. So things have

shifted. And I’m so happy I lived through that phase and enjoyed it and profited from it, not just financially, but what it was just a unique era

to go through.

AMANPOUR: And the unique stars actually of that era, I mean, we have got beautiful pictures that you have shot, Meryl Streep, Goldie Hawn, Diana

Ross, so many others. And we’re going to put some of them up.

What was your big breakthrough? I know, you went to Andy Warhol and “Interview.” You became very close friends with Elizabeth Taylor. We have

talked about that. And she features in this book quite heavily.

But who gave you your first real job? I think it was Tina Brown of “Vanity Fair,” right?

ZAHEDI: What happened was, yes, I had the advantage of knowing Andy and working with “Interview” magazine. I had the advantage of having Elizabeth

as a friend and a mentor, a mentor who took me to Hollywood when she was doing a movie. She took me as her photographer.

But once she left, and I stayed in L.A., it was really hard. I had to go back to the bottom and raise myself up to the level I did. And at one

point, a photo editor at “Vanity Fair” saw one of my photos in “Interview” magazine and decided to give me a break to work with the magazine.

So I got an opportunity. I started again doing little shoots for “Vanity Fair.” Then they gave me bigger ones, bigger ones. And then, at one point,

Tina decided that, you know what, I qualified to have a contract with them, because not only did I do beautiful actresses and movie stars, but I also

did other subjects, regular people, who didn’t look like movie stars.

And I sort of delivered with those images, too. So she felt I qualified to do both. And, therefore, I got a contract.

So, I really am grateful to her for that break.

AMANPOUR: And, of course, she’s part of the formidable couple, Tina Brown and Harry Evans. And he was the great, great editor of his time, and he

passed, sadly. So, it really is — does feel like an era that’s coming to a close.

You also shot the “Pulp Fiction” poster, Uma Thurman, famous, iconic poster of the ’90s. And I just want to ask you. I mean, you’re an Iranian boy done

good.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: I think many in the community can celebrate.

Just in one minute, sum up what you want to do with this collection. You want to also tell the story behind the story.

ZAHEDI: You mean the collection of photographs that are in the book…

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ZAHEDI: … photo?

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ZAHEDI: Well, this book is basically my thank you to the people I worked with, my thank you to the editors, art directors, the celebrities.

It’s not so much — I gave several pages per person in the book, because I just really wanted to thank them, and just relive the experience of those

years.

I put a bit of a distance between the years I did all those photographs. And now I went and did various other kinds of photography. I had

exhibitions, what they consider fine art photography.

AMANPOUR: OK.

ZAHEDI: But I thought, you know what, that was a great period of my life. I can’t just throw it away. I have to pay tribute to it.

AMANPOUR: Well…

ZAHEDI: And so that’s why I did this book.

AMANPOUR: And it’s marvelous.

Firooz Zahedi, thank you so much. “Look At Me.”

ZAHEDI: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

AMANPOUR: And that is it for now.

But we want to leave you tonight with a truly trailblazing woman. She is Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, of course, who, in death, crosses one more

frontier, making history as the first woman ever to lie in state at the U.S. Capitol.

It is America’s final formal farewell before a private burial at Arlington National Cemetery, alongside her late husband, Marty.

That’s it for our program tonight. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again next time.

END