Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, the media played a vital role during the Trump presidency, is of course, especially social media. During this election, eyeballs around the around the world were glued to the vote count. Now, how has Trump changed the press? Ben Smith is media columnist for The New York Times and here he is speaking to our Walter Isaacson about the future role of traditional media outlets and how the Black Lives Matter movement has impacted newsrooms as well.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

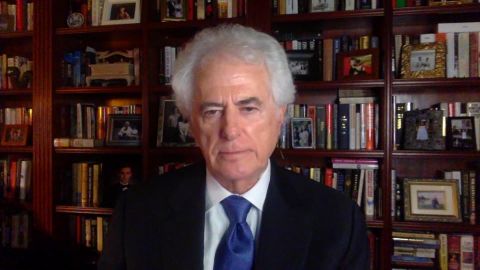

WALTER ISAACSON: Thanks, Christiane. And, Ben Smith, welcome to the show.

BEN SMITH, MEDIA COLUMNIST, THE NEW YORK TIMES: Thanks for having me on.

ISAACSON: Tell me, after this election, what do you think that the media did right this time that sort of pleased you?

SMITH: You know, I think had the biggest test for the media was right at end here where the — you know, where we knew that the vote count was going to be slow because of mail-in ballots, and the media, I thought, did a pretty good job the last couple of months just informing people that they would have to be patient, that it was going to be something like election week. By the end, more than 60 percent of Americans expected that. And then they were pretty careful and patient about, you know, officially calling, it because, as you know, the media plays this bizarrely outsized role in our system where the media’s call is the thing that is sort official and that some people go run out in the streets and honk their car horns. And so, I guess I thought at end they were patient and probably helped give election as much legitimacy as it was going to get.

ISAACSON: What do you think the things that went wrong?

SMITH: You know, it’s interesting. I think that the media was very geared up to fight the last war, you know. We always are, and the last war was Russian misinformation, was very Facebook centric, and I guess I think at times, and particularly towards the end when the “The New York Post” published sort of a strange and shakily sourced story, but basically an ordinarily weird “The New York Post” story, there was still overreaction to it and Twitter block links to it and everybody acted like it was WikiLeaks and it really wasn’t. And I think that was, I mean, probably a mistake. Actually, there were — I’m sure many more ups and downs. But my hard drives get wiped every month. So, you know, that’s long back — that’s as far back as I can remember.

ISAACSON: Near the end of the campaign we saw Trump’s tweets being flagged a whole lot and people fact-checking him in real-time. Is that something that should have been done earlier in the campaign as well?

SMITH: Yes, absolutely. I think it took us all a while to figure out how to deal with a president who says things that aren’t true all the time. And when you call him on them, just blusters through unless you kind of nail him to his seat. And I think what, you know, Axios responded really, really well was refuse to get off a topic and express kind of a frustration diffusion that was authentic and I thought worked well.

ISAACSON: The Twitter sort of stopping people from reading those things, how awkward was it for Twitter to try to figure out how to pick and choose among posts that people should read? Is that something Twitter and Facebook for that matter should be doing?

SMITH: I mean, I just think Twitter has no business doing that. It was something that, you know, other newsrooms were dealing with pretty responsibly. There was, I think, the lesson that a lot of these newsrooms had learned from WikiLeaks was, you know, take your time and figure out what’s actually in here, what’s news, report it out, and the that’s pretty much what everybody was doing. And “The Post” story was like many “The New York Post” stories kind of interesting but not necessarily accurate and people were chase it, and that seemed appropriate. And when Twitter came in and sort of like landed with both feet and said, this is toxic misinformation, we’re going to block it, it called pretty much more attention to the story actually. And also, it’s just — you know, ultimately, I would rather that the editor of “The Wall Street Journal” makes calls on things like that than some product manager at Twitter.

ISAACSON: Well, the editor “The Wall Street Journal” did make a call not to run that story. You wrote a real good column, both about “The Wall Street Journal” not running the full Hunter Biden laptop story but also about the decision desk at Fox News and the fact that it wasn’t interfered with by Murdoch. Tell me, I mean in, terms of reality TV shows, is Rupert Murdoch’s succession reality TV drama that we’re going through and you’ve been covering, tell me about Rupert Murdoch’s involvement with Fox and “Wall Street Journal” and “The New York Post.”

SMITH: You know, it’s interesting. I mean, Murdoch and Fox in particular have been — you know, made it probably the most important institutions of the American right there. Fox has been, you know, essentially Trump-TV. Unclear if it’s, you know, a state-run TV or TV-run state, but, you know, its biggest most widely watched program are the sort of the core Trump movement. And yet, it’s also this chaotic organization with nobody really in charge and Murdoch seems to like it that way. And when it came to calling the election, he kind of let the ordinary machinery of a news organization, which is to say a pretty smart team of people who operate independently of political pressure inform Fox viewers and inform them very aggressively before anybody else that Trump was likely to lose because he lost Arizona. You know, Murdoch himself, I think people often imagine him as this kind of figure pulling every string and manipulating politics and this kind of cinematic way. He didn’t actually come to the U.S. for this one. He has a place in the Cotswold, outside London, which is where he was hanging out. And I think basically did not put his thumb on the scale for Trump.

ISAACSON: Do you think that Lachlan Murdoch was more involved this time?

SMITH: I mean, Lachlan is the CEO of Fox Corp., which owns Fox News, and I’m sure he was involved, but, you know, the truth to Fox since Roger Ailes died is that nobody is really in charge, each the hosts kind of run their own show and basically ignore their bosses, as does the head of the decision desk. The news division, I think, is a little more — operates like a somewhat normal company sometimes, but it’s a pretty strange institution all in all.

ISAACSON: In one of your columns you talk about Trump made old media great again. What do you mean by that?

SMITH: I mean, I think in 2016 when I was working at BuzzFeed, by the way, there was a sense that the “New York Times,” “The Washington Post,” “CNN” had kind of lost their power to decide what was the important. You know, if Donald Trump was giving a speech and people wanted to see it, they would just put it on. At WikiLeaks who’s going to dump a bunch of e-mails, the impulse as well, people are going to see it anyway. And I think, you know, what the research has shown, what we’ve all learned is that maybe people won’t see it anyway and that power of these big traditional news organizations to set the agenda is larger than we have thought. And the funny thing is Trump, of course, knew that all along. He’s been obsessed with — you know, when I was at BuzzFeed, I thought, you know, why is he obsessed with these dying legacy brands, the very reaching and diminishing numbers of people, but I think he kind of understood their ability to set our ability to set the agenda better than a lot of people in these newsrooms did themselves, and I think he exploited that and exploited their weakness and their sense of their own weakness

ISAACSON: You know, back in 2016 you were at BuzzFeed, now you’re at the “New York Times.” Back in 2016, all of a sudden that BuzzFeed, The Daily Beast, The Daily Caller, The Huffington Post, all the new media would be the wave of the future. And yet, in this election, we read the “New York Times,” “The Wall Street Journal,” “The Washington Post,” and the three networks. Has there been a big shift back to mainstream media?

SMITH: Oh, undoubtedly. And, again, I think Trump drove a lot of that shift. I mean, the sort of when you’re covering a beat and the core thing is to get under the skin of the person you’re writing about and have them thinking about you and have their people giving you information. And the fact that Trump is totally obsessed with these organizations is a huge asset to them in covering him. I mean, I think, that the — you know, the tricky thing about this is that, you know, newsprint is still going away. The future is still coming. It’s just in a somewhat different shape, but I don’t think — I think that — you know, I don’t think that the notion that people are going to be, you know, consuming content from all over the place on mobile devices has changed. But I do think that Trump has — Trump and I think, you know, reality, have really kind of restored the centrality of these older news organizations or the surviving ones.

ISAACSON: Well, what about Trump? What do you see would be best for him to be doing now?

SMITH: I think the thing about Trump is that he — you know, he really, really thrives on attention and I think the challenging thing for him right now is that it was understandable that he thought he was getting attention because he was Donald Trump but actually he was getting attention because he was the president of the United States. And you could just already — you know, that’s a thing that shifts fast, and I think there’s a question of how he — I mean, right now, he’s thinking about having these rallies in his, you know, really pointless attempt to contest this, you know, pretty decisive vote against him. I think there will be a question of does he wind of thinking the best way of getting attention to inviting Joe Biden to the White House. But I think, you know, after he leaves, you know, what exactly he does, he’s basically a media entrepreneur. I mean, that’s his real career. You know, how he — whether he tries to capitalize on that is going to be a big question.

ISAACSON: Well, if Trump is a media entrepreneur at heart, do you think there’s room for a new media empire somewhat based on maybe one American news or Newsmax or some of these other more fringe organizations if Trump decides to make it his platform?

SMITH: Well, you know, Fox News has always known a big share of their viewers think that they are too liberal. It’s always been like a third of the Fox audience that thinks the network is too liberal and is open to something to the right. I think the challenge is that — you know, I mean, television news, it’s not a great business. It’s not the kind — it’s not a get rich quick business. I think — and I don’t see really any sign that Trump wants to like operate a business in the hopes of long-term returns. I think he wants cash flow and wants to get paid. And so, you know, you could — maybe you could imagine one America news paying him a substantial sum to license the Trump name, but I think that he’s going to be looking for things to generate cash right away when he leaves the White House.

ISAACSON: Do you think the mainstream media, to use a broad term, the traditional media outlets, are basically biased towards the left or were they biased against Trump, or what biases do you think that they really have?

SMITH: I think Trump put them in a position by attacking them and lying about them specifically where, you know, he was constantly really trying hard to turn us into the opposition. And I think that there’s an argument, you know, do you take the bait, do you avoid taking the bait, are you the bait. And ultimately, you know, it was not a game you could win. I don’t think there was some clever tactical way to avoid that situation, you know, when Trump lies about you specifically. What are you supposed to do?

ISAACSON: Do you think there’s a generational change happening in newsrooms that’s causing the newsrooms to be more activist, more woke and in some ways, less governable by their editors and bosses?

SMITH: I mean, I think there’s a change happening in society, not particularly limited to newsrooms, around — particularly have like employees view their employers, how workers feel in terms of the place they work having some kind of ethical responsibility thing that sort of spilled into newsrooms. The Black Lives Matter movement over the summer really activated that, particularly, and I think particularly among black reporters for whom there had been in newsrooms a kind of tacit understanding that, you know, we want diversity but we also expect you to bite your tongue about issues of race, which is, you know, pretty unfair and kind of untenable. I think, that, you know, that’s — this is sort of being arbitrated right now and these questions of how outspoken can individual journalists be, do you trust them more if you know their biases are more to keep their mouth shut. I don’t think there’s going to be one answer to that. I think different institutions are going to go in different ways.

ISAACSON: Do you think that the media, at least the traditional media, was this time around still, as it has been in the past, fundamentally out of touch with what was happening in the country and even how the vote was really going to go?

SMITH: I guess I’m not sure there’s a media there and the notion that any individual could be fundamentally in touch with a country of 300 million people is complicated. You know, people say, well, I was in Georgia and talked to 100 people and had a different impression. I mean, what is that? That’s a small poll. I mean, the polling was again off and it’s a huge reminder that — I mean, I’m not sure so much that people — we were out of touch, that we were overconfident about what we knew and what is possible to know.

ISAACSON: The press has lost a lot of credibility, both whether it’s on the right which thinks a lot the press is fake news or even among many people who realize that a lot that’s on social media is misinformation or stuff that’s being spread around. How does the press regain its credibility?

SMITH: You know, I think it the answer is going to be slowly. It’s been a real long, slow decline in trust. You know, and, again, it’s among different groups. Different people trust different parts of the media. And I don’t imagine things are going to be centralized around a couple of big outlets. I think people are going to find these organizations they trust and they may be very different in saying different things. I do think younger people in particular are more and more sophisticated about social media, about what not to trust, about kind of being able to hold things in their head that they are not sure are true, and that that’s pretty much — that’s a healthy shift.

ISAACSON: Ben Smith, thank you so very much for joining us.

SMITH: Thanks for having me, Walter.

About This Episode EXPAND

Christiane speaks with U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal about the election. She also speaks with former EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini about what the election means for America’s place in the world. Former attorney for the George W. Bush campaign Barry Richard about President Trump’s potential lawsuits regarding the election. Walter Isaacson speaks with NYT media columnist Ben Smith.

LEARN MORE