Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, behind every vaccine, there is also a volunteer. And you will know this one because he’s our own Walter Isaacson. Master biographer of great minds in science and history as well, and more used to interviewing than being interviewed. But he’s joining me now from New York to share the rare experience of being a guinea pig for the Pfizer trials. Walter, welcome to your program. Tell me what made you do this.

WALTER ISAACSON, JOURNALIST AND PROFESSOR: I’m writing a book that comes out in March on Jennifer Doudna. And the people who created this gene editing technology called CRISPR. And it’s based on RNA. So RNA became kind of my favorite molecule. And when I heard that Pfizer’s along with Moderna were creating vaccines that are very similar to how CRISPR developed, which is a system bacteria used to fight viruses. I said, Hey, I’m going to learn to do by doing. I’m going to sign up. I was in New Orleans, my hometown, pretty easy. You go online, sign up. The next day, they called me. And it’s a way to get involved in science. It’s a way just like jury duty is to do something. It’s far less hassle, believe me, than jury duty, to do something where you can get involved.

AMANPOUR: We were all nervous. I mean, you just had a conversation with Elizabeth Cohen, you know, there are people who are a little bit nervous. Were you scared at any point?

ISAACSON: No, not at all nor was anybody. I mean, that 44,000 people have been part of this trial. I just, you know, it’s not a small number. And there’s no way that there would have been a safety thing where you could have gotten COVID from it, since it’s simply a piece of RNA. Plus, every night they monitor you by cell phone, if you’re in the trial. And with all these people doing it, there were no cases of serious side effects. So, I think I was a little bit more worried about driving down Jefferson Highway dock in the hospital to get into the trial than I was worried about getting the shot in my arm.

AMANPOUR: That’s really interesting because, again, oh gosh, the number of people who say they’re scared of taking it when it comes out. So, do you know whether you got the actual, you know, vaccine or did you get the placebo?

ISAACSON: I don’t know. I mean, you could try to find out by antibody test. But I want to play it by the rules, do what you’re supposed to be doing. So they made me look away. There were two doctors in the room and one of them said to me, she looked at me and said, looked me in the eyes. And I was doing it. She had very blue eyes like a hospital mask. And when I started to turn away and look at the needle, she said, no, no, no. Look at me. I said, well, would I be able to tell just by looking at the syringe? She said no, probably not, but we’re very strict so that you don’t know. Now, they did promise us that once something is authorized, they’ll unblind us. Otherwise, you know, we just drop out of the trial if they refuse to unblind us, and people wouldn’t do trials anymore. So you get this assurance that if there’s an authorization for this vaccine, they’ll tell you whether you got the placebo or not. And you’ll be not first in line, but you’ll be there ready to get the real vaccine when it happens. And I think that makes people confident. Yes, let’s join these trials. I’m not going to be a pure guinea pig. And also it helps a trial work well, because if they didn’t unblind us we’d all just quit the trial and take another vaccine, as opposed to staying in the trial and continuing to give them data.

AMANPOUR: Now, look, you know, you’re not just an ordinary citizen. You’ve done so much study and research into science, your books, your biographies. You’ve just mentioned the book you’re writing about the founder of CRISPR. What do you feel about the history of vaccine hesitancy and the spike I suppose these days?

ISAACSON: You know, throughout our history, we’ve had citizen involvement in science. And, you know, when you talk about the polio vaccine, you know, I’m old enough to remember the March of Dimes, where we all chipped in to make sure everybody could get that vaccine. And what people like Elvis made sure they showed themselves getting the vaccine. And, boy, down in New Orleans, there was no question that you’re going to get that vaccine because you couldn’t go to swimming pools or anything without fear. I think it’s also something important now, which is that people are a little bit intimidated by science. And in some ways, our society has become a bit, not just intimidated, but sometimes anti-science. So it’s important for all of us to feel connected to think, like we try to understand maybe our computer so we can be connected to the digital revolution. We should find ways we can connect to this biotech revolution. And by being part of a clinical trial, which is totally safe and doesn’t take up much time, you engage with science in a way that both reassures you, But you feel a little bit less alienated from the science. And I think that’s one of the great problems of modern times is, it’s not just the citizens fault that they’re skeptical of science. But in some ways, science hasn’t been open enough to let people participate in the science. And the coolest, easiest way to participate as a citizen in science is just go online, not just for the coronavirus vaccine, but there’s, you know, once I signed up, they were offering me dozens of clinical trials I could be part of. Sign up for clinical trial, it’s really good and sign up with your family.

AMANPOUR: That’s good advice. And actually, on this program, we reported on a lot of youngsters here in Britain, who wanted to do that and do their bit as well. But let me ask you about the mRNA aspect to all of this. I talked a little bit about it with Elizabeth, what is the big breakthrough, historically, as far as you’re concerned with this type of vaccine?

ISAACSON: Here is what is huge. It’s just a piece of genetic code. And in the future, kids who know how to play with genetic code are going to supplant those who play with digital code. Why, because with these RNA vaccines, it fights this COVID-19. But let’s suppose another virus comes along, and it will in the next year or two or three years, there’s another coronavirus or any type of virus that comes along. This can be easily reprogrammed. All you have to do is get the genetic sequence of the new virus, and a college biology student in a lab, in one day, can do the reprogramming of this sequence. So you get a new vaccine to fight any new virus that comes along. And that’s what we need in this, you know, we feel like we’re in the Middle Ages with wave after wave of recurring virus attacks, you know, MERS, and SARS, and COVID. Here, with RNA exams, you won’t have to spend a lot of time. And you can, by the way, reprogram these RNA type vaccines to do other things, even detect cancer. That’s what CRISPR is all about, which is the subject of my book, “The Code Breaker” is coming out in March, which is it can do things like edit our genes, it can fight cancer, and now we know it can fight viruses and be reprogrammed to fight each new wave of virus.

AMANPOUR: Tell me more about Jennifer Doudna. Obviously, she won the Nobel Prize with her colleague for chemistry because of this CRISPR technology. What more are you finding out that we haven’t known in the public domain yet?

ISAACSON: It’s a wonderful tale of Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, her partner, who was born in Paris, figuring out how to use CRISPR, which as I said, is simply a piece of RNA connected to a scissors, an enzyme that can cut DNA. And now, they figured out how to target it. So if you have a gene say for sickle cell anemia, it can be edited out. The Chinese scientist couple years ago used it unauthorized in order to make designer babies that wouldn’t be susceptible to AIDS. What happened when they did it, and then another wonderful guy named Feng Zhang is at the Broad Institute at Harvard. They also all figured out how you do it in human cells. And there was a big competition between the two. It was a race to figure it out. And then, there’s still a patent battle. But the interesting thing about the COVID pandemic is both camps, as well as other people said, now that we know this technology, we’re going to not compete with one another but put a intellectual property in public so we can make detection kits. I mean, this is going to come along in the next few weeks. It’ll be just as interesting, which is simple, CRISPR based detection kits that will detect that coronavirus, or for that matter, any other genetic problem you may have. These will be the type of tests you can put on your kitchen counter. You know, just almost like a pregnancy test with a little strip. That too will bring science into our lives. Because just like the iPhone, people will be creating apps for these new CRISPR-based tests so they won’t only test for coronavirus. They might test for your gut biome and what your — or for cancer. So this is a whole new age of biotechnology, that CRISPR, and the use of this wonderful molecule RNA. You know, it’s sibling, DNA, used to get all the publicity.

AMANPOUR: Yes, indeed,

ISAACSON: DNA is certainly the nucleus of a cell and doesn’t do anything, whereas RNA actually goes to work and takes instructions and goes to the protein making part of the cell.

AMANPOUR: DNA, I’m going to stand up. I’m going to stand up for DNA, important forensic tool as well. But before I let you go, I want to ask you about, you know, you’ve interviewed at least two of the members of the Biden task force on coronavirus. And I just want to play this heartbreaking sound bite from a nurse in an over strapped hospital in South Dakota. Let’s just play this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JODI DOERING, SOUTH DAKOTA EMERGENCY: Yes, I think the hardest thing to watch is that people are still looking for something else. And they want a magic answer. And they don’t want to believe that COVID is real. And their last dying words are, this can’t be happening. It’s not real. And when they should be spending time facetiming their families, they’re filled with anger and hatred. And it just made me really sad the other night. And I just can’t believe that those are going to be their last thoughts and words.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Do you think a new administration can change the tone because that is tragic?

ISAACSON: Absolutely. And I think that’s the most important thing, even with these vaccines, it would be good to have this administration figure out a way to how to get them distributed, where you go on a website and sign up for when you’re going to take it and where. But the most important thing is to restore faith in facts and in science. And this goes back to what I was saying about we should all find ways to connect as citizens to science. Joe Biden did that when he run the cancer task force, and he did it when his son, Beau, tragically succumb to cancer. It made him understand the science better. I hope we can do that in ways that are less tragic than the clip you just showed or what Joe Biden had to go through. Whereas if we all feel connected to science, we’ll make more rational decisions.

AMANPOUR: Yes, it’s really important. Walter Isaacson, thank you so much.

ISAACSON: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

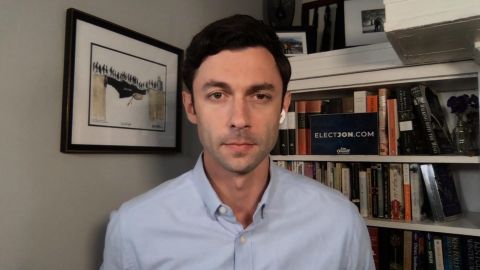

CNN senior medical correspondent Elizabeth Cohen reacts to today’s announcement that Moderna’s coronavirus vaccine is 94.5% effective. Walter Isaacson discusses his experience as a participant in Pfizer’s vaccine trial. Senate candidate Jon Ossoff (D-GA) discusses his race against Sen. David Perdue. Sociologist Nicholas A. Christakis discusses COVID-19’s ripple effect on society.

LEARN MORE