Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.”

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

JOHN KERRY, U.S. SPECIAL ENVOY FOR CLIMATE CHANGE: We have to be ambitious, all of us, because we have to get the job done.

AMANPOUR (voice-over): The U.S. back in the game. We profile two urgent climate cases.

From Pakistan, the young activist Aliza Ayaz joins us, and from a small Pacific island nation struggling to stay afloat, Anote Tong, former

president of Kiribati, joins us.

Then:

STEVEN YEUN, ACTOR (through translator): Remember what we said when we got married? That we’d move to America and save each other?

AMANPOUR: Pursuing the American dream. “Minari” tells that quintessential story, the resilience of a Korean family setting up a new life in America.

I will speak to lead actor Steven Yeun.

And:

BILL GATES, CO-CHAIR, BILL AND MELINDA GATES FOUNDATION: Only by really bringing the cost down can we make the case to them that they should stop

building new coal plants.

AMANPOUR: Bill Gates tells our Walter Isaacson how to avoid a climate disaster.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

The race against climate change starts up again in earnest. Here in Britain, Prince Charles today warned that there is no time to waste. And

with the United States now back in the Paris climate agreement this weekend, America’s so-called climate czar, the former Secretary of State

John Kerry, pledged that his country would lead a global response and warned that there is only nine years to get our environmental act together.

As he says, millions of people just have to look out their windows to see the effects of this emergency.

Pakistan is one of the most climate-vulnerable nations in the world. Monsoon rains are getting more extreme every year. And Kiribati, one of the

world’s poorest countries, a small island nation in the Central Pacific, faces complete obliteration, as rising sea levels threatened to submerge

it.

The former president of this fragile paradise, Anote Tong, joins me now, and, from Pakistan, the activist and U.N. Youth Ambassador Aliza Ayaz.

Welcome, both of you, to the program.

President Tong, can I ask you, because you have been at this for a long, long time, what does it mean to you to know that the United States is back

in the game and prepared to again lead this challenge against this climate emergency? Do you expect something to change significantly?

ANOTE TONG, FORMER PRESIDENT OF KIRIBATI: Thank you for allowing me this opportunity, Christiane.

And, yes, when I first heard that the U.S. was withdrawing, it was really was out one of the greatest disappointments. I have always believed that,

without the participation of the U.S., very little can be done.

And so, with the U.S. coming back on board, we’re hoping that a lot of the disappointments that we had expected following the change in administration

from the Obama administration, we are hoping that there would be a renewed momentum, adding to what followed the climate discussions in Paris.

So, I am very excited. I’m hoping that something — we can hopefully avoid a lot of the tipping points that we were on the verge of surpassing.

For countries like Kiribati, I think we have already crossed many…

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: Yes. Yes.

TONG: Sorry.

AMANPOUR: Before I turn to Aliza Ayaz, I want — it’s OK.

I just want to ask you, because we have said that you face a potential submersion. How bad is it there in Kiribati? How urgent is the situation?

TONG: Well, we are — we have already been experiencing these impacts.

We have communities who have had to relocate. We have king tides washing over the island and flooding, destroying crops, sometimes destroying homes.

And so these are becoming more frequent.

The question will be, as it gets worse, where do we go from here? And I think this is the question that we really not — have not been able to

answer, nor has the international community in being able to address it.

AMANPOUR: All right, well, I’m going to come back to you on, where do we go from here?

But let me get a status report from Pakistan and Aliza Ayaz.

You have been named a U.N. youth representative, ambassador for this. You are at — now you’re in Karachi, but you’re at University College London.

What is it that has propelled you into the forefront of this fight?

ALIZA AYAZ, UNITED NATIONS YOUTH AMBASSADOR: Lots of different factors, influences, I think.

Moving around the Middle East and Europe has given me exposure to the stark reality of the climate crisis. I think what’s special about being a climate

activist is that more and more people my age, we’re talking about the problems for people and really recognizing that human-environment

connection exists.

And we’re not just concerned about the polar bears. Our message isn’t just about saving the rain forest or saving whales. It’s about (AUDIO GAP) don’t

just need protection.

There’s also increasingly research on the role of young activists, all the way from (AUDIO GAP) 24 years that are playing a leading (AUDIO GAP)

because they’re there, and they’re not being paid to be there.

So, I think because young climate protesters don’t want to represent someone else’s agenda or their message is strikingly direct and

unvarnished, we can say a lot of things that other adults can’t.

AMANPOUR: So, let me play for both of you, actually, this sound bite from John Kerry, because let’s face it. The U.S. was absent without leave for

the last four years.

And like it or not, the U.S. is one of the biggest polluters and has the biggest throw weight in terms of the ability to help effect and propel

change.

So, let me just play what John Kerry said about the urgency of this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

KERRY: In rejoining, we have got to be really honest with each other. We have to be humble. And, most of all, we have to be ambitious. We have to be

honest that, as a global community, we’re not close to where we need to be. We have to be humble, because we know the United States was inexcusably

absent for four years.

And most of all, we have to be ambitious, all of us, because we have to get the job done.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, President Tong, I want to go back to how we left it a moment ago.

You said, we have got to see where it’s next going. So, here’s the climate czar, for all intents and purposes, saying that we have to be humble and

ambitious. Where do you think, particularly for low-lying islands like your own and in the Pacific region, what’s the immediate process that has to

start?

TONG: Well, let me say that I absolutely have confidence in the — what Secretary Kerry will do. I know he’s very genuine.

But at the same time, we need to be able to come up with the answers. The question is, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has actually

predicted that, whatever happens, whether we cut emissions to zero, islands, countries like (INAUDIBLE) Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands in the

Pacific Ocean will continue to be submerged over the decades.

The question is, what can be done either to maintain the integrity, so that — of the island, so that our people can continue to live there, or find

alternative homes for them, should that be the case?

And so that needs to be addressed. We — so far, I mean, we are — the issue of climate-induced migration, I don’t believe has been fully

addressed at the international level. Hopefully, Secretary Kerry can provide the momentum in order to address these very critical issues for

countries on the front line, like mine.

AMANPOUR: So, migration is a really, really important point.

I want to just, for our viewers, show a little clip of two women from your island nation talking to a film crew not so long ago. It was part of a

documentary that was called “Anote’s Arc.”

This is about a tsunami on your island. Here she — here they are.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): We told him about that crazy day, when the water came rushing in. He was filming people building the

seawall. We told him how the sea came inside our house.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: It was really a strange day.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Yes, it was like a tsunami.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: I was worried that, as we slept, it might flood the house. I didn’t think it would, because it didn’t last time.

But the next day, the house was flooded. We were lucky it was during the day.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, President Tong, you can see the very real danger.

So, when you say moving people for their own good, you don’t mean like people fleeing like refugees. You actually mean an organized removal of the

entire population and putting them somewhere else?

TONG: Yes. Yes.

I have always rejected the notion that our people should become climate refugees. And the reason is because we do have more than adequate time to

prepare them for it, because we know it is happening. It’s inevitable. And we should plan for it.

And so my response to that is that, instead of having our people become climate refugees, they should be given the preparation, so that they can

migrate with dignity, people with skills to move into new societies to become worthwhile people with dignity, and to be able to contribute in a

positive way to the communities they move into.

That’s — I think it can be do — it’s very doable. We don’t want to repeat the same kind of mistakes that have happened in the migration, the massive

migration of people from North Africa into Europe.

I think that’s a lesson that we need to learn from, and certainly not to repeat.

AMANPOUR: And, Aliza Ayaz in Pakistan, your country is obviously much, much bigger. I mean, you have got several hundred million population in

your country, and you can’t lift the whole population to another country.

But there are major issues, right? I mean, it’s not a greenhouse-producing nation, but there is the monsoons. There are the trees and the logging

that’s going on. What are the biggest issues when it comes to climate in Pakistan?

AYAZ: Well, more than 11,000 scientists in 153 different countries have declared a climate emergency.

The U.K., Canada, France, Ireland, New Zealand, they have all declared a climate urgency, but Pakistan is still far away from that. And I think, as

part of this emergency declaration, we should be contributing to the climate change mitigation and decarbonization efforts possible in our

capacity, and promoting what is a circular economy for sustainable development.

I think such important measures will include utilizing renewable sources of energy and taking steps to reduce our emissions. Even though we are

contributing less than 1 percent of the global carbon emissions, like you mentioned, we should still keep in mind that national emissions will

increase due to population, economic, industrial and urban growth.

So, a major co-benefit of emission reduction will be improvement in our air quality, as the (AUDIO GAP) and this will (AUDIO GAP) pollution-related

diseases as well.

And I think another important aspect of the emergency declaration — or this issue, rather, is that on climate change adaptation, without which we

will observe major and momentous disasters throughout the country.

And in the very first year of this decade, as climate change, Pakistan witnessed a wide range of weather anomalies and related natural disasters,

landslides, glacial lake outbursts resulting in flash floods up in northern areas, the change in current precipitation patterns, leading to on — urban

floods, and the longer-term drops in Sindh, where I’m based.

The recent wave of this unusual warmer winter season in the month of December is a present manifestation climate change. And this is why I think

climate change adaptation must be a priority for all sectors, and it should be incorporated as soon as possible in their policies and programs and

action plans.

I think, as a nation, we need to take the issue of climate change with a seriousness.

AMANPOUR: Yes, Aliza, when all those young people around the world following Greta Thunberg were marching all over the world, they were in

Pakistan as well.

And it looks like your government is talking about increasing solar power, but also electric vehicles, trying to bring that in. There are also,

obviously, complaints about corruption, about the — perhaps it’s the inability to actually get it organized in a way that protects it and that

actually makes a difference on the ground.

Can you talk to me — plus, of course, is the plan to build — or, rather, to plant, I think, it’s 10 billion trees, because loggers and people just

cut them down, which has its own negative climate impact. Where are those issues headed now? Do people have confidence in the government’s electric

car program or in the tree planting program?

AYAZ: I think there are mixed reactions here for the local population.

And half the population believes that this is going to a long way, a long- term benefit, and the other half of the population still doesn’t believe climate change is an issue that’s going to affect them.

I think that Pakistan’s government needs to change and demonstrate through implementation and take a leadership position in climate change mitigation

and adaptation. The private sector and civil society both should also join hands to have a fully inclusive and coordinated response.

And in such a holistic way, we will be adopting to whole-of-society approach. In terms of the proposed adaptation actions, you mentioned

electrical vehicles, the one billion tree plantation.

I think they’re good benefits in the long term, but they’re not immediately going to get us any results, since we’re a long way from that, a lot of

political and technical issues. But I think, in the short term, we have got different projects and technical assistance with objectives around

multisector projects, but they’re to be used for climate, and water disaster management, as well as effects of building climate resiliency for

irrigation infrastructure.

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: OK. Let me move to President Tong in Kiribati.

Some of the methods that I read about trying to save your island are just incredible. I mean, literally trying to lift the islands higher by a

process of dredging. Obviously, you have got the sandbags. You have got all of this kind of stuff.

Is that — I mean, your current president is trying to do this massive engineering job. Is that going to work?

TONG: Oh, I’m sure it will work. But the question will be, how sustainable will it be? Will it last for the next 20, 30 years or the next 100 years.

Given what is happening on the — with the environment, with climate change, I think it will be — it’s — it won’t be for a very long, long

period of time. But the question is, when is it? What at what point in time do we give up, OK?

And, of course, there is this desire to be able to continue to live on our home islands. And I understand that fully. And I think I actually subscribe

to the same concept.

But the question is, how sustainable, how much longer can we remain on the islands as we continue to raise the islands above the rising seas? This is

very much an engineering question. And I’m afraid I have never been able to get a full answer to ,how do we do it?

But, yes, I understand if we can remain on the islands for the next 50 years, so why not? I think the last thing we want to do is to lose our home

island, our identity, our culture.

So, yes, I fully subscribe to the idea. And, in fact, I had considered the same options. I looked at building floating islands, even the very thing

that the current administration here in Kiribati is thinking about. And, yes, I think it’s clutching at straws, but why not? What options do we

have, apart from losing our home, losing our identity?

(CROSSTALK)

And so these are the some of the things that are very, very difficult for people to — right — to accept.

AMANPOUR: Yes, it’s very stark, obviously. And I think the current president has reached out to China to get them to put their expertise at

the disposal. That’s worried the United States.

So, can I ask you, President Tong, what you expect at the end of this year from COP 26, the delayed next Paris — rather, the follow-up to the Paris

climate accord, which the U.K. will host in Glasgow at the end of this year?

TONG: Well, basically, the same thing that I was expecting that the Paris discussions which I attended, and really a greater accountability and

greater response by the international community to this challenge.

We need to work collectively. And the question is, how meaningful are these things that are coming out of Paris that will come out of the COP 26? How

meaningful will they be? Are they likely to be for countries who are very seriously challenged, who stand the real possibility of being submerged?

Because mitigation is not an issue. And I follow what my friend from Bangladesh is saying. It’s not always — it’s not simply about mitigation.

It’s about building the adaptation, the resilience to withstand the — what will be happening with climate change.

So, I have always been hoping that, following the COP 26, we in Kiribati will be able to have solutions, something like a firm commitment to provide

us with a home next few decades.

And I don’t know…

AMANPOUR: OK…

TONG: … if this will be possible, because the focus has been on saving the rest, but not those that have gone too far past.

AMANPOUR: Well, we are very pleased that we have been able to put this spotlight on faraway atolls like yours.

So, from Kiribati, President Tong, and, from Pakistan, Aliza Ayaz, thank you both for joining us, two very strong advocates.

Now, the climate crisis is, of course, inextricably linked with this pandemic, and in the United States, coronavirus has exposed a troubling new

strain of hate crimes against its Asian community now, in the wake of what Trump used to call the China virus or the China plague and kung-flu.

Immigrants to the country have regularly suffered racism even as they give their all to the American dream. And a new film, “Minari,” is making waves.

It’s about a Korean family trying to build a new life in rural Arkansas as landowners and farmers. And here’s some of the trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

YEUN (through translator): We said we wanted a new start. This is it.

Daddy’s going to make a big garden.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: What a wonderful day to be in the house of the lord. If you’re here with us for the first time, please stand.

(APPLAUSE)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: What a beautiful family. Glad you’re here.

How does your daddy like that new farm? He draw things good, doing things right?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Yes.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

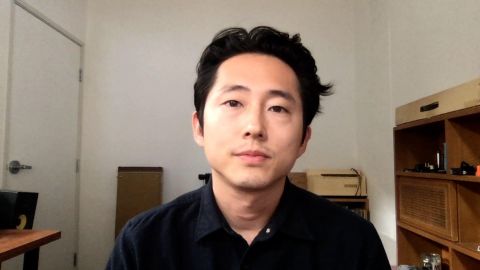

AMANPOUR: Now, Steven Yeun plays the dad who you saw in the red cap. His name is Jacob.

Steven Yeun is joining me now from Los Angeles.

Welcome to the program.

It’s a remarkable film. And it’s an unusual story of the journey. Tell me what drew you to it. Obviously, you’re also Korean American. It’s about a

Korean American family. There must be parallels. But what drew you to this script?

YEUN: You know what? I think, for me, what was really profound about the script was that it was confident in its own point of view.

For me, it’s something that I always wanted to say. But it wasn’t captured in very literal ways. It was really just about the fact that this story was

about this Korean American family, in and of themselves, that it wasn’t juxtaposed to the majority or needing the majority in their family or in

their story to justify their existence.

But it was just a story about the humaneness of these people. And that was really refreshing.

AMANPOUR: And toiling and struggling to reach the dream, which was actually the dream of your character, the father, Jacob.

And the rest of the family — we can talk about this — were not necessarily fully on board with what you want to do, leaving California,

coming into rural Arkansas to be a farmer.

Here’s a little clip that we want to play. It’s you and David, your son in the film, and you’re trying to find water in order to plant, obviously, on

the land.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

YEUN (through translator): Never pay for anything you can find for free.

With a house, we have to pay for water.

(through translator): But for our farm, we can get free water from the land. That’s how we use our minds. Got it?

Did we use that stupid stick? How did we find this?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR (through translator): We used our minds.

YEUN (through translator): We used our minds.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: It’s really a very revealing clip.

The story, it sort of shows this tension between you trying to make a better life for your wife and your kids, but how difficult it was. Do you

succeed in the film? I mean, I don’t want to — I don’t want to do a spoiler alert. So you can tell us how much you want to tell us.

And what is the tension within the family as you try to pursue this American dream?

YEUN: I think it goes beyond whether there’s success achieved or not.

I think, really, the story is about a family assimilating to themselves, to each other. I think, for my particular character, Jacob, he’s kind of on a

singular mission. And he puts the weight of his family and their existence on his back.

And, in some ways, he kind of makes it his own and only his. And I think it’s through the difficulty and through certain situations that he comes to

realize that this experience is shared, that their family — that the family is going through this all together, and that it’s not just on him.

And so Jacob, his journey is really understanding that his family is so much more than their functions, that he is so much more than their

functions, that they are just all in it together.

AMANPOUR: I thought the character of David, your son, and the grandmother who comes to live with you, the mother of your wife, who comes to live with

you, is really poignant.

David has a bit of a heart condition, we understand. And the grandma is actually trying to bolster his confidence, as well as anything else. Let’s

just play this little clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): The church bus is here.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): You go ahead without David.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS: This just gets better and better.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): There we go. Which drawer attacked you?

You lifted that heavy thing? And you put it back all by yourself? Goodness.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: There are so many of these stories where the grandparents are such a glue to the family.

What did you take from her role? And also “Minari,” the name of the film, I think the grandmother introduces that.

YEUN: I think the grandmother, for me, represents so many things, but I think one special thing is that her point of view of how to love the

children is unencumbered with duty.

There’s no sense of needing to teach them anything or making sure that she’s correcting them. But, rather, she can just kind of — just see from

her point of view how to love these kids for who they are, regardless of anything.

And I think that’s a luxury that perhaps a grandparent has that a parent doesn’t have. But, as a parent myself, that was really profound for me.

AMANPOUR: And minari?

YEUN: Well, minari is a beautiful metaphor.

Isaac, our incredible writer and director, taking a little bit from his own life, grasped onto this plant that really spoke so deeply. It is supposed

to represent, on a larger note, minari, actually, you harvest the second growth of it. So the first growth dies, and the second growth thrives, and

you harvest that.

And it also purifies the soil and the water around it. And it was kind of representative of, I think, from my point of view, a boundless love that is

represented at the hands of the grandmother, and so, hopefully, something that we can all kind of relate to.

AMANPOUR: You said, Isaac, the writer/director, drew on his personal life, his personal story.

You also — I want to ask how it how it reflects on your own experience as well, because you were born in Seoul, and then your family moved first to

Canada, before coming to the United States.

We have this picture of you in kindergarten. And a close look at it, it’s quite revealing, because you have got all the all the kids in the

kindergarten, and then you’re sort of a little bit away from them. They’re all jammed together, and you’re sitting a little bit away.

What was it like being a little Asian kid in North America at that age? What do you remember?

YEUN: I think a lot of things happened.

For me personally, I think it was the beginning of maybe feeling the feelings of isolation, of kind of having the framework that you understand

up into 4 or 5 years old, when I immigrated, kind of reconstituted or kind of broken down.

And the difficulty of immigration for second-generation kids is also that you’re further and further pulled away from your parents’ generation,

through language, through your assimilation. And it happens slowly over time.

And I think that has been kind of a profound theme overall in my life, that I think initially in my life served as something to either ignore or to be

considered something sad. But I really do view it as this wonderful new perspective in my adult years of just understanding the singular place from

which I exist and I kind of speak from.

And so, yes, it’s been a crazy ride.

AMANPOUR: Yes, it’s been amazing, the reception.

I think you have got all sorts of awards and — well, nominations, anyway, in this award season. There’s some controversy, I think, about one of the

awards in which the film has been — let me just get that straight.

It’s been named in the foreign film category, right, for the Golden Globes. And some think that it should be actually in the English — in the

whatever, American English language Category for best film, because it is by an American director, it is in America. By far, the required percentage

of language is spoken.

What was your view on that?

YEUN: On a whole, I think I’m very thankful to be part of this project. And I’m thankful that I get to be part of something that challenges, I

guess, the ways in which institutions and rules fail to acknowledge the nuance and depth of real life.

This country and many other countries, but this country in particular, is made by the eclectic nature of so many different points of views, so many

people, so many different cultures kind of coming together to service the collective feeling of this country.

And, sometimes, we only get to see a specific picture of that. And what I love about “Minari” is that it challenges those notions. And I think people

are hopefully made aware of what we’re trying to say and what it kind of runs up against.

But yes, I’m really glad for this film.

AMANPOUR: And you have spent a long time and you are very well known for the series “The Walking Dead.” So, you’ve already been challenging, I

guess, stereotypes and you have a lot of — from what I read anyway, mail and response from viewers whether they are Asian Americans coming from

wherever, saying that you sort of blazed a trail for them. Talk to me a little bit about that.

YEUN: Yes, I don’t know. I mean, you know, there is something new that I think that a lot of us are touching on Asian American representation and

just kind of existence in America is something that I think is hard to pin down. Not because there isn’t that existence, but because oftentimes, it is

framed between Asia or America. I think that America tries to understand Asian America through Asia, and in reverse, Asia tries to understand Asian

America through America. And I’m coming to realize that it’s really its own space and its own thing and its own culture, and it is a part of this

country.

And so, for me, I have always kind of had this desire to speak as honestly as I could from my point of view, I just never really had the framework or

the words or the context to kind of say that to anybody. But in this work that I have been able to do and feel so lucky to do, I have been able to

touch upon some things. And so, yes, I am just trying to really speak from me and try to keep doing that.

AMANPOUR: You know, just to go back to you you, Steven Yeun as opposed to Jacob Lee in the film, I read that when your father decided to settle, and

you’re going to tell us where he decided to settle in the United States, he took a map, and he said to your mother, I am going to spit, and wherever my

spit lands, we are going to go there. Is that true?

YEUN: That is actually my uncle. My uncle did that.

AMANPOUR: Your uncle.

YEUN: Yes, my uncle did that. He was the first one here and he did such a crazy thing. He used to be a runner for (INAUDIBLE), like giant massive

barges and the crew that would occupy those things. And he kind of just took it on a whim, met my aunt, and spit on a map and went in a direction

and created something from nothing, a very immigrant existence.

AMANPOUR: And you ended up where, your family then?

YEUN: We settled in Michigan. I’m from Michigan.

AMANPOUR: So, you know, I started part of the lead to this by sadly remembering and reminding that Asian Americans through American history

have come across their own very severe prejudice and racism, we remember what happened in World War II in the interments with the Japanese. But now,

because of all this coronavirus and the language that was used by the former administration, we have actual hate crimes, there’s somebody who has

been killed.

Did you imagine that that might happen, you know, in 2021? Do you feel still that there is that latent prejudice against Asian Americans?

YEUN: Absolutely. You know, there is always prejudice. I think people have a tough time seeing each other clearly. Sometimes we like to see people

just by their identifiers or in the ways that they feel different from each other. And it is no surprise to me that, you know, the literal ways in

which people tend to view the world sometimes ends up manifesting as hate and fear.

It is sad that certain people get to amplify that and push that out and make that bigger than it needs to be and create terrible situations for

individuals. So, yes, there is absolutely racism by the Asian American community.

AMANPOUR: And just very quickly. “Minari” obviously is getting a lot of Oscar buzz and you’re getting buzzes potentially a nomination as best

actor, it would make you the first Asian American to be so nominated. What does that mean for you?

YEUN: It’s complicated. You know, I think it’s — you know, it’s not tied to the last question that you just asked me, but I think in some ways it

is. Just for me, I am really just trying to speak from my own place and I’m very thankful for any acknowledgment of my work. It’s really cool.

But, you know, these identifiers of being the first Asian American thing, I am very glad to aid in breaking a precedent or the changing of rules and

these institutions in the ways that which we all collectively understand reality. But, I also really, you know, can only speak from my place and I

only want to speak from my place. And I am Asian American and that’s something that I can never change and I am proud of. So, I intend to not

die on any hills. I really just want to continue to continue evolve and grow and speak from my own place.

AMANPOUR: Well, good luck to you. “Minari” is a lovely film. Thank you so much for joining us, Steven Yeun.

And we return now to our story, which is, of course, the climate crisis. While billionaire philanthropist, Bill Gates, has been working hard to help

end this pandemic, he has never taken his eye off the growing threat to our natural world. Gates does not believe that the situation is hopeless, but

he does believe it requires action and fast.

He has put together a plan to reach zero global greenhouse emissions in his new book, which is called “How to Avoid a Climate Disaster.” And here he is

with our Walter Isaacson.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane. And Bill Gates, welcome back to the show.

BILL GATES, AUTHOR, “HOW TO AVOID A CLIMATE DISASTER”: Thank you.

ISAACSON: What have we learned from the pandemic that’ll help us in the fight against climate change?

GATES: Well, the general idea that the government should think ahead about bad things, we expect experts to make those investments. So, you know, we

have building codes to minimize earthquake damage. We’ve got the Defense Department to do war games and be ready for attacks.

Sadly, in the pandemic category, we did not invest at all. And so, our ability to diagnose travelers coming into the country and get going was

very slow. Likewise, for climate. You know, we haven’t up the R&D budget. There’s a lot of various of emissions that were really not making much

progress on.

So, sadly, the climate change, it will incrementally get worse and worse and there’s no tool like a vaccine that, all by itself, even if you make

the mistake that helps you to get out of it.

ISAACSON: In the new book, you talk about how you first became interested in energy through the foundation work and the whole concept of energy

poverty. Explain that to me.

GATES: Yes. So, near 2000, the Gates Foundation got going. And so, I was making trips to Africa, parts that I had never been to before and seen not

only the lack of electricity but also the precarious nature of the ports (ph) there who are overwhelmingly farmers. And, you know, some years their

crops are less productive, some years they fail altogether.

And so, thinking about, gosh, let’s get electricity to this continent, but what is this constraint of climate change and how bad is it going to be? I

had time to sit with the experts. I was very lucky that they put huge effort into finding the right people to educate me, and that got me super

worried about what it means not just for Africa but for the entire world.

ISAACSON: But isn’t there some conflict between trying to make sure that places like Africa get the energy that they need in order to become

productive and growing societies and the issue of the reducing the carbon emissions on this planet?

GATES: Yes, absolutely. At some level of wealth, the poorest countries, whatever the costs are for them to go green should get subsidized. The

extra cost I call the green premium. Now, when you move up to middle income countries even including India, Brazil, China, we can’t afford the pay the

green premium there. So, only through innovation are we going to be able to save India, please use the green approach as they’re building basic

shelter, air conditioning, lights at night, you know, the very basic things that their citizens demand.

ISAACSON: But they are getting a lot of the energy from coal fire plants that are done cheaply in China, and China gets to export to them. What do

you do to try to resist that?

GATES: Well, coal, sadly, is the cheapest form of energy right now in most of Asia. The renewable prices have come down, that’s fantastic. But often

the — you know, where the renewable sources, when you need the power, they are far away. Even in China, you have to build the transmission.

The Indian network getting capital into it is tough because you have a lot of financial debts there and electric bills that are not paid. And so, only

by really bringing the cost down can we make the case to them that they should stop building new coal plants. Almost all of the new coal plants in

the world are connected to India or China, and that is why China is so far only committed to reducing the emissions by 2060.

And so, we’ll have to, you know, help to some degree, but mostly take the incredible power of innovation which the U.S. still is the — by far the

leader in that and surprise people on how affordable we make it. Not just for electricity, but also for steel and cement where China in those

categories has also got the biggest footprint.

ISAACSON: Well, look at what happened in Texas in the past few days. The grid has been a mess, it has not worked. Some people there are blaming it

on the fact that they were depending on windmills and turbines. What went wrong and what should we learn from this cold snap we’ve just had and the

electricity problems it caused?

GATES: Well, this particular problem had nothing to do with an overdependent on renewables. Although, some wind went down, the big drop

was in the natural gas capacity in one of the reactors. These things can work in very cold weather but they just saved the money and didn’t

weatherize them. I mean, natural gas plants and wind work in North Dakota, Alaska, Antarctica. And also, their grid structure where they’re pretty

isolated from the west and the eastern grid, that meant that even when they had problems, they couldn’t import power.

There are weather conditions that — you know, like cold fronts over the Midwest where the amount of wind does go down, but that wasn’t what we ran

into this week in Texas.

ISAACSON: You know, after reading your new book, I became so much more convinced of how critical it is to actually get nuclear power more into the

mix. Tell me, what are you doing and what should we be doing to make it safer, cheaper and to make it so it doesn’t frighten people?

GATES: Yes. Part of the beauty of nuclear is that on a long-term basis it actually has been quite safe. I mean, Chernobyl was horrific, you know,

some awful mistakes were made. The biggest problem with nuclear today, besides these challenges at the public acceptance, are the economics.

Westinghouse went bankrupt because their reactors had such big cost overruns, and there’s very few plants, only two being built in the U.S.,

because natural gas is so cheap. It’s outcompeted existing nuclear and coal very effectively. In fact, only the renewables in a complimentary fashion

are what is really being built in the U.S. right now.

The exciting thing is that if we start from scratch and we stop using high- pressure water and we do digital simulations of all the safety and how to minimize the size of everything, we can build a reactor that is competitive

and is dramatically more safe. The government had a funding round that TerraPower and some other companies, TerraPower is the nuclear fusion

company I helped back. So, we won the funding, 50 percent from the private side, 50 percent from the government to take five years and build a demo to

show that it is dramatically different.

And so, that, you know, gives me a lot of hope that nuclear can play a role. I got involved just because, because of the need of climate reasons

to have that as a very scalable green non-weather-dependent way of making electricity.

ISAACSON: Tell me why this nuclear power is safer.

GATES: Today’s reactors have a lot of high pressure. And if you get a leak, then things want to get out. The fundamental problem is that you

split the uranium atom and that gives you an immense amount of energy. The remaining pieces are radioactive. And so, you need to basically guarantee

that the waste is not going to get out particularly up in the air and, you know, Chernobyl was where that was so awful.

Now, we’ve known that we can build reactors that just by physics principles, there is no pressure in the reactor, there is nothing that

wants to leave the site boundary. You have to move away from water and use a sodium metal coolant that many experimental reactors have used. And so,

that’s the TerraPower approach. It means that there’s enough new there that — you know, it’s a big engineering budget, but we get huge reductions in

the cost. And so, you know, even just in terms of having low-cost electricity, it is a big contribution.

ISAACSON: I was surprised to read in your book that transportation, which I always thought was a big emitter of the greenhouse gases, is actually

much smaller than things like cement as you say or steel. Is there some way to try to handle the problems of cement and steel?

GATES: Those are particularly hard. And if you look at the cost of doing it in a green way, for cement, you have to double the price. With cement,

you start by heating limestone and that’s a chemical reaction that releases CO2 to free up the calcium. And the heat you need, you need very high heat,

1,400 degrees. And so, you generally burn natural gas.

You have two reasons why that’s CO2 emitting, replacing the chemical reaction is going to require either capturing that CO2 or some ingenious

approach, and we are backing to break through energy venture group I created, we are backing a lot of ideas about new ways of doing cement. But

cement and steel, I would put at the top of the list of the things that are very, very hard to make the green product without a huge green premium.

ISAACSON: You have always been focused on solving the problems through technical innovations. But when you were doing the global poverty work, it

seemed to me that you eventually began to think it’s not just about innovation, it’s about government and getting involvement of policy as

well. That got you a bit out of the comfort zone, and you start having to deal with the policy and politics, not just making a new vaccine. Explain

how that worked?

GATES: Yes, I thought that if the Gates Foundation funded the creation of new vaccines, that the uptake could be handled by others and I could stick

to the meeting with scientists and what we know about biology.

In fact, what I found out early on as we looked at all the cost of childhood death, there were — the two biggest killers, pneumonia and

diarrhea, the rich countries had vaccines. Now, they didn’t need to be invented. In fact, they were getting to the kids at the lowest risk of

those diseases. And so, instead, it was about finance, it was about delivery, how you staff a primary health care system.

And so, amazingly, two of the things I am most proud are the Gates Foundation funding of Gavi, which was to buy and deliver those vaccines and

the global fund which was focused on malaria and TB and HIV, and those — our partners are completely the other governments.

So, you know, I am, you know, a friend of governments. You know, recently, we have been raising money for coronavirus vaccines. I’m on the phone a

great deal not only with the U.S. government people, but, you know, government leaders all over the world. And so, yes, that is a turnaround

from what I thought, hey, just science, just innovation, you know, leave the government alone was the way to go.

ISAACSON: And in your book you talk about having to do that turnaround when it comes to climate as well, you can’t just deal with the technology,

you realize you have to deal with government. Tell me, in that dealing of government, how much of a change has it been dealing with the Trump

administration and now dealing with the people around President Joe Biden?

GATES: Well, certainly on climate, the Trump administration was trying to stop things from being cancelled. And so, you know, the tax credits, which

had been very helpful, largely staying intact. The energy R&D budget stopped going up, which it had done under Obama, but it was maintained even

though the executive branch said to cut it, Congress kept it flat.

Now, under Biden, they’re prioritizing climate. The R&D budget will go up quite a bit, including support for things like nuclear. The regulations

around how do we get transmission out. Hopefully, this builds back better initiative, will include climate-related things like better transmission

capability. The tax credits, we need to apply them to new areas like carbon capture and storage.

And so, the dialogue is now very, very intense. And I think that some good things will come out of that. Having said that, we don’t want climate to be

a purely partisan issue where, you know, when one party is in power, you make progress, some of the other ones in power you don’t. Because when

you’re saying to people build steel mills or power generators, you know, every once in a while these policies will be in place and then they won’t,

you can’t make the hundreds of billions of investments in going green unless the core of the issue is agreed upon, even though, you know, it is

good, actually healthy to have disagreement over the tactics of the role of the government and private sector in how we get to the goal.

ISAACSON: A lot of the companies and individuals are reducing their carbon footprint by buying offsets. How do you do that personality and how does

one do it in a way that’s not just green washing or like buying indulgences for some pope and it’s actually a real — it actually does cover the carbon

emission?

GATES: Yes. So, there is quite a variety of quietly of offsets. I’m paying Climeworks, which up in Iceland, does direct air capture and takes the CO2

and puts it mineral deposits for millions of years. I’m buying clean — green aviation fuel for my plane, and it wasn’t available up in Washington

State. So, now, I’ve made the largest individual commitment to them that they have gotten. And so, I have that available. You know, obviously, using

solar panels, electric cars.

Another one that’s interesting is that when they are doing a new low-cost housing project, I can put up the capital so it’s electric heating and

cooling, they benefit by having lower monthly bill and I take the credit for the fact that that’s a much lower carbon footprint.

So, overall, I paid $7 million a year, which averages out about $400 a ton. Now, it just shows that it’s not scalable, you know, that’s way too

expensive. And so, you know, innovating down green premium, you know, so, I’m buying these products, hopefully, that gets that going.

In fact, we want to create an overall buying program called Catalyst where we get governments and companies, and maybe individuals, to get the money

in, because when you buy green products, if it’s the one that can, with volume, get very cheap, you are not only to that specific carbon reduction,

but by bringing the price down, you’re causing that whole sector to accelerate its transition.

ISAACSON: At the end of the book, you talk about what we can do, including people like us who are not worried particularly about jet fuel for their

jets. What is it, each one of us should be doing each day?

GATES: Yes. Well, we really all have three roles. We’ve got our political voice and educating other people about why we care about this, hopefully on

a bipartisan way. We’ve got our dollars as consumers. So, buying electric car even though it still has a bit of a tradeoff, contributes to the cause.

You know, likewise, these new types of meat production products. And all the products you buy, you’ll have a green rating over time, and will get

the qualities of those to be (INAUDIBLE) direct your dollars according to your beliefs.

Finally, you know, wherever you work, they can make a contribution, whether it’s their buying power, their skillset and, you know, we see the finance

sector or the tech sector all coming in and saying things like, OK, we can afford to buy green steel and cement. And so, let’s — we’ll help get that

market going or we can make our data center so it’s not just sort of green, but it really never takes any hydrocarbon generation to help power that

data center.

And so, you know, as companies — it’s great that they’re kind of competing to say, OK, we care about this cause because we are a good citizen, because

our employees want us to, you know, that can help to get even the hard parts of the problem on that learning curve.

ISAACSON: Thanks, Bill, and thanks for the book, “How to Avoid a Climate Disaster.” Thanks for being with us.

GATES: Yes. Great to talk to you.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Bill Gates, always on the case.

And finally, tonight, a woman who’s going to extraordinary lengths to avoid COVID lockdown at just 21 years old. Britain’s Jasmine Harrison is now the

youngest woman ever to row solo across any ocean. She arrived in the Caribbean on Saturday after a grueling journey across the unpredictable

Atlantic.

Here she is getting her land legs back after a trip which lasted exactly 70 days, 3 hours and 48 minutes. Now, this shiny record is lifting spirits

back home here in the U.K. where the professional sailors have sadly just missed out on winning the America’s cup race again. Britain’s only been

trying since the contest began 170 years ago. But undaunted, the team vows it is determined to bring that trophy home next time.

And that is it for now. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

END