Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR.

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR (voice-over): G7 foreign ministers in the U.K. for their first face-to-face meetings since COVID. Senator Amy Klobuchar talks about

Biden’s foreign policy goals American policing and why she’s bringing on the antitrust fight.

Then:

YE WINT THU, JOURNALIST, DVB: This is the last fight for the country. They don’t give up.

AMANPOUR: On World Press Freedom Day, we shine the light on dark powers repressing reporters.

Plus:

MALCOLM GLADWELL, AUTHOR, “THE BOMBER MAFIA”: Try and drop a bomb with any accuracy off a plane when it’s being blown sideways at 200 miles an hour.

It’s impossible.

AMANPOUR: Malcolm Gladwell tells Walter Isaacson the fascinating story of World War II’s Bomber Mafia.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

And the U.S. secretary of state, Antony Blinken, has touched down here today, as G7 foreign ministers gather here in the U.K. for the first in

person meeting since the pandemic began.

There will be laying the groundwork for the big summit next month, when their presidents and prime ministers will meet in Cornwall. And it’ll mark

President Biden’s first trip abroad since his inauguration in January.

According to British Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, high on the agenda this week will be Russian disinformation. Of course, this is the kind of

stuff that thrives online via social media.

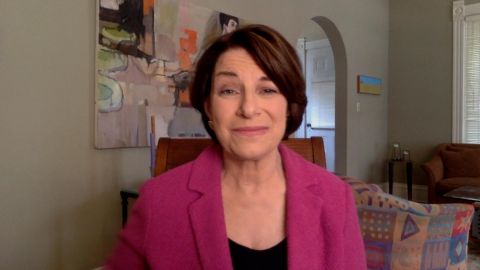

And joining me now on the need for digital oversight is the Democratic Senator from Minnesota Amy Klobuchar. Her new book is called “Antitrust:

Taking on Monopoly Power from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age.”

She’s also chair of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust.

Senator, welcome to the program.

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: Can I start by asking you just, because the secretary of state is here, President Biden is coming here next month, to sort of tell me what

you think the big agenda for him will be talking to his colleagues in the G7, and particularly along the line, as I mentioned, what Dominic Raab

said, Russian disinformation and sort of interference in democracies is high on their agenda?

SEN. AMY KLOBUCHAR (D-MN): Exactly.

So, number one is to shore up our relations with the G7, with our allies.

We know the ups and downs of the Trump era and the drama, needless drama so many times, especially when we were in the middle of the pandemic.

Number two, the pandemic and getting through this, looking at what’s happening in India, looking what’s happening around the world, and joining

forces to try to help the entire world get through this.

Number three would be what you have referred to, is these players like Russia, who have forever sowed discontent not just in America, but also in

the European nations and across the world, to really take this on in a unified way, and show that we mean what we say.

And when you look at disinformation, you look at not just the hacking into the U.S. elections and that attempted hacking into it and everything that

came out of that back in 2016, improvements made in 2020, we know, in protecting our elections, but still attempts made all the time, and you

look at what just happened with Solar Sky (sic).

So, that is going to be a major topic. And I have always believed you just can’t take it on with the U.S. alone. You have to do it with our allies.

And I do hope they discuss this issue of monopolies and taking on monopolies across the world, because we have things we can do with Europe,

including this recent App Store investigation that was just concluded, with action the way.

There’s many examples on that. So there’s going to be a lot on the agenda. And let me not forget climate change, something that has been a major focus

of President Biden. So, I personally am so glad we’re into governing again and working with the rest of the world and not just waking up every day to

see what the latest mean tweet is.

And one of the best ways you change the world in a good way and improve relations is by reaching out to your allies with seasoned hands, like

Secretary of State Blinken, Jake Sullivan, and the like.

AMANPOUR: I’m going to get to antitrust and the topic that you’re most energized on right now. You have just written that book.

But, first, I want to ask you, because, obviously, President Biden, maybe in reaction to sort of the shock therapy of the Trump presidency, he’s

writing a very strong wave of public support around the world. And he also is in the United States.

But I want to ask you, because he’s on the road today pushing the part of his big plan that’s the American Families Plan. How much — how difficult

is it going to be for him to get bipartisan support, when a new poll says that only — as much as 70 percent of Republicans still think that he’s not

the legitimately elected president?

KLOBUCHAR: Listen, despite that — and I do wonder about those numbers, given where — Republicans I talk to at home.

Despite all that, what I see is, when he passed that Rescue Plan, working with Democrats in the Senate and in the House, that was overwhelmingly

supported by a lot of Republicans and Democrats. That’s why it passed.

That’s why the Republicans, after it passed, really couldn’t go after it very much, because people were so excited that the vaccine was finally

getting distributed, that our economy was getting shored up, that we were helping small restaurants, that we were helping families that were trying

to juggle their kids on their knees, their toddlers on their knees and their laptops on their desks, and teaching them first graders how to use

the mute button.

So, regardless of what that poll says, these policies, the reason that President Biden is popular right now and the reason that we have been able

to continue to get things done is, there is support for his policies. There’s no doubt about it. There are other polls that show that, from

Democrats, Republicans and independents.

So that’s all I got right now. I’m just working on helping my constituents to get through this pandemic, regardless of if some people are questioning

the election or what they’re saying about it. I have got to keep my eye on going forward, at the same time taking on the social media companies, if

they’re not doing enough to stop this misinformation.

AMANPOUR: Right, which is why I put that out there…

KLOBUCHAR: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Because the next question is, how much of that is — do you lay at the feet of the social media companies which, inter alia, you’re taking

on with your antitrust book, and, I guess, legislation, whatever you can do as a senator?

KLOBUCHAR: Well, I, first of all, have to look at the conveyor of most missed information. And that would be the former President himself Donald

Trump, which was a reason, of course, the riot, the incitement of the insurrection, that the impeachment was taking place. So we have got to

start there.

But the second piece of it is that the way the social media companies have handled this, where they are the gatekeepers, the monopolies in each of

their respective areas, has led to no competition, basically.

So, maybe Instagram or WhatsApp could have developed bells and whistles for privacy and misinformation. Why did that not happen? Because, in the words

of Mark Zuckerberg in an e-mail that was discovered in the House investigation, he would rather — his words — buy than compete.

And, as he noted, these companies were nascent. They may not be big enough. I’m paraphrasing that. But he said at that time, but if they grow — this

is his words — they could be disruptive to us.

AMANPOUR: Right.

KLOBUCHAR: So, to me, that’s the very definition of a monopoly. They bought up stuff so they wouldn’t have any competitors. And then, for

instance, in the case of Google, 90 percent market share on search engines, what incentive do they have to develop the kinds of privacy protections

that we need?

That’s why Europe’s been going after this. That’s why we do. I don’t question their success. I’m pleased they have developed into incredible —

and developed incredible products. But at some point — in American history, we are a country of entrepreneurship and competition. We provide

the check and balance. We go after that with our antitrust laws.

And the time has come for that.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you, because, I mean, people who watch are a little sometimes disheartened, like tech experts and the tech journalists,

when they watch a Zuckerberg or whoever come to Congress, and, frankly, tie Congress in knots.

And they’re just so much savvier about tech than those, I’m sorry to say, senators and congresspeople who usually do the questioning.

KLOBUCHAR: That’s OK.

AMANPOUR: And he has come up in the past with a pretty snappy line, whereby he says, oh, you got a problem with me? Well, it’s either me or Xi.

In other words, my dominance is a lot better, wouldn’t you say, than having the leader of the world’s biggest communist state be dominant.

What do you say to that?

KLOBUCHAR: You know, through history, that is not how we have gotten ahead to where we are.

We got ahead to where we are because we actually believed in capitalism and competition. And I believe in that and so do a bunch of Republicans and

Democrats. So, if you look at it that way, and you look at the mess they have created on misinformation and the like, you realize, yes, it’s good to

have some strong companies, but it’s also good to keep developing new companies to be able to compete with the Chinas of the world, something

that is a big part of Joe Biden’s foreign policy that you’re going to hear about, I’m sure, when he comes to Europe.

And that is making sure that our people that believe in democracy and capitalism are on the same page. And so I just believe it’s just what he’s

saying right now to support big.

And I want to see more companies and more competition. And, by the way, if you think there’s problems for workers right now with wages, it’s really

hard for them to compete when there’s only one big guy in each of their areas. And throughout history, when we have taken on monopolies, whether it

was the breakup of AT&T, the chairman, former chairman of AT&T, said AT&T became stronger because of that, because they were forced to compete.

It brought down long distance rates. It brought up the cell phone industry into this incredible competitive business. Or you look at the breakup of

Standard Oil, going way back. Or you look at our early founders, how they didn’t want to have to buy all their tea from the East India Tea Company.

This is a country of entrepreneurs. And in the end, that’s how you compete in the global economy, by unleashing the power of capitalism and workers

and new ideas.

AMANPOUR: So, you brought up all — all other industries you’re also writing about in the book.

But in terms of big tech, because I guess it’s such a powerhouse right now, Republicans, many also have problems, but they normally say, oh, we’re

being blocked, and it’s about censorship, whatever their complaints are with big tech.

My question to you is, is there — I mean, you want to do something, presumably, to legislate. I don’t know whether you want to go to Europe

way, or is there a hybrid? But do you think there is any resolution with Republicans to get to some legislation on this?

KLOBUCHAR: Yes, I do.

And that’s what — I wrote this book in a way that reached out beyond the Democratic base. And I wanted to make the story and the history alive, with

incredible stories about, like, the founder of the Monopoly board was actually against monopolies and going through history.

And then I end with 25 ideas. And several of those ideas, many of them, are bipartisan. And I will give you some examples. The agencies right now, FTC

and the Department of Justice, Antitrust, can’t take on the biggest companies the world has ever known with duct tape and Band-Aids.

That’s why Senator Grassley and I want to change the fee structure when people apply for mergers, so that that helps pay for the lawyers we need to

take on the cases. They literally are a shadow of what they were during the Reagan administration.

Secondly, something you know from your international work and show and focus, look what happened in Australia with Google and Facebook. They

basically tried to walk on an entire industrialized country. So, that’s why Senator Kennedy and I, along with Buck and Cicilline in the House, have a

bipartisan bill that says, let’s let our news organizations be able to coordinate on negotiating with the tech companies when it comes to paying

for content.

Looking backwards at what we have in terms of the tech — a lack of competition, looking at pharma, we have got dozens of bills that are

bipartisan, that take on exclusionary conduct and make sure we have generics in the market when it comes to pharmaceutical prices.

So, I think it’s there. We just — every time we try to advance something, honestly, Christiane, some company has influence over some senator or some

rep, and it’s like a game of Whac-A-Mole. You get it through the Trump administration, you get it through the Senate, and then someone in the

House doesn’t like it.

So I’m just ready to expose all of this, because I think that I need to do this. And it’s why I wrote the book “Antitrust,” so people would come to my

side. We need a major public support for moving forward on monopolies.

AMANPOUR: And how about on policing and justice?

As you know, of course, the George Floyd policing and justice bill is out there. President Biden would like to see it passed before the anniversary,

which is May 25. And I have heard some of you, some officials in the United States saying there might be some momentum. Do you think this — it will

happen?

KLOBUCHAR: Yes.

You know the tragedy, the murder of George Floyd happened in my state, not far away from where I am right now.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

KLOBUCHAR: And that trial was a moment of redemption, the witnesses that came forward who had been holding this burden for nearly a year, where they

said — one of them said, I literally keep waking up at night thinking, what could I have done?

Well, what happened with that trial, including with the police officers that testified against Derek Chauvin, is that justice came out of that.

But we shouldn’t confuse that kind of justice, accountability with true justice, because true justice is making sure this doesn’t happen again. It

is putting in some standards in place for policing, everything from banning choke holds, to changing what the standard of force is.

And Cory Booker is leading our effort. I’m one of the co-sponsors of the bill and have been involved. But Cory Booker is leading the effort. He is

negotiating with House and Senate. And I just think you have seen more interest than ever before, because it’s really hurting everyone. It didn’t

just happen in Minnesota.

AMANPOUR: But I wonder if it’s — clearly, this has had such an effect, as you say, not just in Minnesota, way beyond, but on you. You are from

Minnesota. You were the county prosecutor there.

And at the time, you oversaw cases of police shootings, and let the grand jury made the decision about whether police should be charged, whether

charges should be brought. And you have said subsequently that you wish you had made the decisions yourself, as the county prosecutor.

You have gone through an evolution as well, which may be what the country is going through on this issue.

KLOBUCHAR: Yes, and I’m — back then, that’s how it was done. The idea was, take it out of politics, have the grand jury decide. That is part of

it.

But the big part of it, Christiane, is that the standard needs to change. It is not every moment that you have the video that you have in the George

Floyd case, that you have all the police officers testifying at a hearing.

And so, by changing the standard of proof from where it is to necessary — to get to necessary from where it is now, you really, really have to pass

something federally and tie it in with what the states are doing, and that would make a big difference.

AMANPOUR: Senator Amy Klobuchar, thank you so much, indeed, for joining us.

KLOBUCHAR: OK.

AMANPOUR: So, you just heard us discussing disinformation.

And yet information as a public good is central to marking World Press Freedom Day this year. Every year, this day is a sobering reminder of the

essential need for truth and facts amid an ongoing and ferocious battle against them, something U.S. Secretary of State Tony Blinken took note of

in London today.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TONY BLINKEN, U.S. SECRETARY OF STATE: We’re seeing every day the work that journalists are doing around the world in increasingly difficult and

challenging conditions to inform people, to hold governments and leaders of one kind or another accountable.

Nothing is more fundamental to the good functioning of our democracies. And I think we are both resolute in our support for a free press.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And perhaps he’s especially interested in that, because he reminded the press there that he had started his professional career as a

journalist.

This year particularly highlights how a global pandemic and the rise of authoritarianism silences the press, for example, in Myanmar, where the

military coup in February has forced independent journalists into hiding.

Correspondent Paula Hancocks gauges the fallout now.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

PAULA HANCOCKS, CNN CORRESPONDENT (voice-over): Ye Wint Thu spent the first weeks after the military coup on the streets of Yangon talking to

protesters.

THU: This is the last fight for the country. They don’t give up.

HANCOCKS: Anchor for media company DVB, he and his colleagues rushed to the office on the morning of the coup to collect their equipment, then work

from home.

A month later, the military canceled their media license, along with others. They then went underground.

THU: I did my job, whether it’s dangerous or not.

HANCOCKS (on camera): When you were able to report on the streets, I mean, what concerns did you have? What dangers did you face?

THU: You know, I could die. I could die on the street. Like, I had to be really, really be careful not to get arrested on the street.

HANCOCKS (voice-over): He was placed on a wanted list. When one of his reports was shown at a military press conference, a friend told him to run.

THU: So, I got a call: “So, you’re — it’s your time now, so run.”

So, I had to run like within 10 minutes.

HANCOCKS: In hiding, he is still working, despite the daily Internet shutdowns, relying on images from protesters. He says this military

crackdown does not feel new. When he was 4, his father, a democracy activist, was imprisoned for 10 years.

More than 70 journalists have been arrested since February 1, according to the U.N. More than 40 of them are still behind bars. Some have not been

heard from since they were taken.

SHAWN CRISPIN, COMMITTEE TO PROTECT JOURNALISTS: Myanmar’s press freedom crisis is becoming effectively a humanitarian crisis for its journalists,

right? They’re being held in prison. There are reports that they are being tortured in prison. Many are in hiding, and others are leaving the country

altogether.

HANCOCKS: Ten years ago in Yangon, I spoke to journalists who were cautiously optimistic for an opening up of media, as the military appeared

to accept limited democracy.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I wouldn’t say that you can’t have articles about the military, but they’re going to be looking at it very closely.

HANCOCKS (on camera): And crossing out quite a lot?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, yes.

HANCOCKS (voice-over): Those days are long gone.

The photographer who filmed this does not want to be identified, as he is also on a warrant list. He says he can now only film security forces from

behind closed doors. When he could still go outside and cover the protests, he said he never felt safe.

He describes one sit-down protest in Mandalay where security forces suddenly started shooting into the crowd.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): They didn’t care who they hit or who they killed. I was so worried. And I didn’t know where to run. I just

grabbed those around me and ran. We were all so scared. I was running for my life.

HANCOCKS: He says he hasn’t been paid since the coup, a problem for many inside the country. Daily life is a struggle. He’s hiding in a separate

place, away from his wife and young son, to try and protect them.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): I had to send them to another safe house, as the military was arresting anyone in the house if they can’t find

that person on the list.

HANCOCKS: He praises the efforts of citizen journalists doing the job that he is no longer able to do, documenting the brutal military crackdown,

risking their lives to show the world what’s happening in Myanmar.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Paula Hancocks reporting there.

Now, for more on press freedom, I’m joined from Mumbai by Indian journalist Rana Ayyub.

According to the Network of Women in Media, 175 journalists and media workers have died from COVID in India since the pandemic began.

And from Washington, D.C., I’m joined by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author and former director of Voice of America Amanda Bennett.

Welcome, both of you, to the program.

Amanda, can I just start with you first? You have had that role as director of VOA. So, you have had the big picture. You’re also on the board of the

Committee to Protect Journalists. And you heard the caseworker there calling it a humanitarian crisis for journalists in Myanmar.

Of course, it’s happening in Hong Kong. It’s happening many, many places we look right now. From your sort of global, big picture perspective, why is

this happening now? What are the main forces?

AMANDA BENNETT, FORMER DIRECTOR, VOICE OF AMERICA: Well, for one thing, you’re talking about the pandemic.

And for the other thing is, we are aware of it now, but, honestly, the threats to the press have been consistent over decades. Most of the

repressive regimes which are now growing in power and strength, for example, in China and Russia, where they’re throwing journalists out of the

country, are — they’re kind of flexing their muscle, as you can see in Hong Kong, and the military flexing its muscle in Myanmar.

But threats against journalism are absolutely nothing new. There’s been over the past three decades probably about more than 40 journalists a year

killed for the past three decades.

AMANPOUR: Of course.

I just wondered. We just seem to see a rise in authoritarianism, particularly in the — in Asia right now.

BENNETT: Yes.

And that’s clearly true that the first thing an authoritarian government wants to do is to seize control of the press. That’s historically been

absolutely the case. It’s part of the roots of Voice of America. Voice of America was created during World War II to broadcast behind Nazi lines.

So, authoritarian governments and crushing the press go completely hand in hand.

AMANPOUR: So, let me turn to Rana.

And we have talked before, particularly on the rather draconian government new restrictions in Kashmir, which is I believe where some of your family

are still. But we just said what the organization has said, 175 journalists have died of COVID.

You yourself, very sadly, have suffered the loss of family members in this latest round, this latest surge. And on top of that, even Reporters Without

Borders are saying that India is 142nd on the list of the most dangerous place for a journalist to be.

RANA AYYUB, “THE WASHINGTON POST”: Well, Christiane, I completely agree with Amanda when she says that the first target of authoritarian regimes is

to basically control the source of information.

As we talk, there are multiple reports in India that we have lost close to 56 journalists in the last 28 days of the pandemic. They have succumbed to

COVID-19, because most of the journalists, they’re also front-line warriors, are not vaccinated. They do not have — they do not have the

mechanisms. They do not have probably safety measures to kind of save themselves.

So, journalism comes last on the list of priorities. When they’re not being killed by the virus, the journalists are being silenced for speaking truth

to power. In India, we do not really have an independent press, so to say. So, we have two — we have parallel realities in India, a reality which is

shown by our domestic media, which is basically prostrating to Narendra Modi.

And then there are the international media, journalists who work with international media, who have been speaking truth to power, and which is

why, about a day ago, one of India’s leading television networks dedicated one hour of it programming to calling international journalists,

journalists in India who basically write for international publications, including my cover “TIME” magazine, as anti-nationals, who basically are on

the payroll of the CIA.

And not just that. Yogi Adityanath, who is the chief minister of the largest state in India, where COVID is ravaging, and there are deaths upon

deaths, has told journalist that if at all they report on oxygen shortage, they will — there will be a case against her.

A journalist I was speaking to yesterday who sent me a video of close to 456 funerals in one day requested me, begged me to not take his name in my

“Washington Post” report, saying that, if I take his name, the government was silence his voice.

What does that say about journalism in present-day India, especially at a time when India is facing the worst of its humanitarian crisis? This is

what we say, a holocaust, that we are living every day, as the dead toll in India has crossed 4,000 deaths a day. And that’s still the official figure.

AMANPOUR: Right.

It is extraordinary to hear journalists being threatened, depending on what stories or not to write certain stories. And I did bring up some of the

sort of data so-called denial or manipulation with the national spokesperson for the BJP Party when I spoke to him last week.

But I want to ask you, Amanda, because America has not been whiter than white, despite the First Amendment and the constitutional protections, for

a free and independent press. After — under the four years of the Trump administration, it was really difficult, and the whole sort of tarring of

truth as just a load of fake news. It was very, very difficult.

And it had a bad effect and a follow-on effect around the world. So, you had a personal story. You had a personal experience with this. How

dangerous was it for — and do you think American has recouped some of its reputation — to also be tarnished with this idea of fake news that the

president himself was banding around?

BENNETT: Well, Christiane, you’re right. It was a very difficult, difficult time.

And I take a couple of lessons from it going forward. And one is that what the United States does matters. And so the fact that Secretary Blinken is

out talking about a free press, meeting with the Committee to Protect Journalists, meeting with the CEO, the acting CEO of the U.S. Agency for

Global Media, which runs the Voice of America, a well as other organizations, Kelu Chao, he is stating now that the United States is

returning to its traditional support for a free press.

What the United States does matter. When the Committee to Protect Journalists meets with governments to talk about governance where — as

journalists who are imprisoned, something happens.

And so we can look back at the negative impact this period has had, but we can also look at the fact that one of the things that kind of save the

Voice of America during the time it was there, after I had left, was the fact that an entire society basically rose up to defend and protect —

lawyers, whistle-blower organizations, organizations like the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press, other media, citizens, and, in

fact, legislators on both sides of the aisle.

There was a fundamental understanding the free press was important. So there’s a lesson I take away from this, which is that what we do matters,

and we need to make sure that, in the United States, we keep hold of the very, very unbelievably rich principle we have in the First Amendment.

AMANPOUR: So, Amanda, let me ask you about your specific personal situation, because it appeared — and you said that you were a victim of a

political sort of backstabbing. You resigned. You wrote a letter about it.

Tell us, remind us what happened.

BENNETT: Well, I was the director of Voice of America, which is the top editor there. I had been there for more than — almost four years. I was

appointed during the Obama administration, but continued for almost three years during the Trump administration, which is what the Voice of America

is supposed to do.

It is a nonpolitical organization that is supposed to transcend political parties and changes in the leadership. At some point, people around

President Trump and President Trump himself began to much more directly speak to the Voice of America, then tweet, that it was producing fake news,

that it was enhancing the propaganda of the Chinese government, that we were on that side of the Chinese.

And then I, along with my deputy, chose to resign, because, once the new director had been appointed, the new CEO of the agency that oversees all

the media properties, we knew that we were going to be fired, which indeed happened to every leader of the other organizations within that group.

And we felt it was important to be able to keep a connection with the organization that we had led to let them know that we were going to be

there to support them during very difficult times, and they showed enormous bravery during that time.

AMANPOUR: To be clear, as you said, President Biden has reversed, you know, a lot of that. I mean, he’s put in a veteran journalist now as head

of VOA. But let me ask you, Rana, because we were talking a little bit about — you talked about, you know, the pro-Modi press, for want of a

better word.

A couple of years ago, Freedom House said India, the world’s most populist democracy is also sending signals that holding the government accountable

is not part of the press’s responsibility. The media have become widely flattering of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. So, we talked a little bit

about that. But we also — I also wanted to ask you, what is the flip side? What is the danger of slavishly reporting and just being praise worthy,

particularly in a pandemic? And you have seen in these local elections where there was some backlash against the ruling party at the polls.

Well, Christiane, Indian media has been responsible for the rise and rise of Narendra Modi’s popularity including asking him questions about how does

he prefer to eat his mangoes during the mango season. I mean, it’s absolutely disgusting when just about the last couple of weeks Indians were

dying and they were requesting for oxygen on social media, the prime minister’s social media handle was tweeting about the thousands of people

who were attending his election rallies that in turn, of course, led to the surge in the second wave in India.

And you see the Indian press frustrating without asking the tough questions. So much so one of the ministers in the Modi government has

turned — has got a turn for journalists like us to report international media calling us prostitutes.

AYYUB: From afar, some of journalist who are speaking (ph) the truth to power, including my college, Goilan Cage (ph), who translated my book in a

regional language in 2017 was found dead outside their house. There are consequences for reporting the truth.

As far as the lap dog media, which we call in India, and you’re worth a flip side, well, I’m sure history will be kind and objective to journalists

like us and when there’s a lot of people who do not know what the truth is. But, unfortunately, these journalists and most of them are journalists who

speak — who are the Hindi language journalists that has a huge penetration in rural India end up listening to this narrative as opposed to we the

anglicized English media who talk to the “Wall Street Journal” or the “CNN” and their truth is not as acceptable.

But it’s extremely important that we have the (INAUDIBLE) of journalists in India that is hellbent on just doing public relationships. And that’s

unfortunate. Journalism is dying (ph), it’s loaded. We say India is on a ventilator at this point of time when we are dying for the lack of oxygen.

I think journalism in India is on ventilator. Even at a crisis like this when the government is fudging data, the government — like, for instance,

the government says there are 4,000 deaths in a day, multiple local journalists have been sending out reports and sending out data that points

out that there are at least 10 times the number of deaths that the government is putting across.

Still, there is not a singly question from India’s mainstream media as to why is Narendra Modi not taking a single press conference? Why is he not

taking the top questions from the Indian media? Why has he not — why has the prime minister of the (INAUDIBLE) democracy not taking a singly press

conference in the last six years?

You know, Indian journalists were pressing “The New York Times” when “The New York Times” published names of all the deceased by — you know, who

died of COVID-19 last year. And there were three things, why is something like that not being done by Indian public indications? Why is Modi not

being asked the tough questions on the frontpage of our newspapers? In fact, when Joe Biden offered help to India, the headlines in Indian

newspapers was Narendra Modi makes Joe Biden prostrate before India. That’s what the headline is. That’s what the posturing is.

And you could imagine. But are these the only journalists? No.

AMANPOUR: OK.

AYYUB: There are unsung journalists who are doing an unpopular journalism, Christiane. And the world must (INAUDIBLE). I stand all journalism in India

who are bringing the truth at this point of time —

AMANPOUR: Right.

AYYUB: — to (INAUDIBLE) to their life. I’m proud of my colleagues.

AMANPOUR: I mean, yes, there’s a huge amount of, we should say, great work coming out. But I want to ask you or — and I want to ask you, Amanda,

because the Modi government, as we’re talking about India, last week asked Twitter and Facebook to take down certain postings that were — they deemed

unflattering to them. They said it was spreading disinformation. The government did.

So, I want to ask you because this year, UNESCO’s theme for World Press Day today is information as a public good. Have you thought about how

journalism can survive and navigate as a public good when, as we were discussing with Senator Klobuchar, we live in this era of digital dominance

and social media dominance and the exponential ability to pass along information that may or may not be true and often isn’t?

BENNETT: Well, Christiane, I can address that a little bit and that is that, yes, there’s several pieces to this. One is kind of trying to figure

out how you handle this fast-moving gigantic system and how you deal with the clearly burgeoning amount of disinformation. But there’s another piece

to that and that’s the place where I think that I can be the most use and that is looking at the piece of the reliable, truthful, you know,

professional news media because of financial issues is just really collapsing. And so, there’s both pushing back at disinformation and there’s

also providing good information. Both of those things are under threat right now.

My personal choice is to spend my time trying to deal with providing the good information, filling up the system with something that is losing

increasingly now. I think there’s a lot of work for other people to do in pushing back on disinformation as we’ve just heard.

AMANPOUR: Indeed. And, of course, The Indian government, every time we bring this up, they always deny attacking journalism. But it’s really,

really important discussion on World Press Freedom Day.

Rana Ayyub, Amanda Bennett, thank you so much for joining us.

Now, the sort of inside out version of current affairs with bestselling author and host of the “Revisionist History Podcast,” Malcolm Gladwell. His

latest book, “The Bomber Mafia,” explores new details about the bombing of Tokyo during World War II. Here’s Walter Isaacson speaking to him about the

technological innovation and moral conundrums that scientists and generals wrestled with at the time.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON, CNNI HOST: Thank you, Christiane. And Malcolm Gladwell, welcome back to the show.

MALCOLM GLADWELL, AUTHOR, “THE BOMBER MAFIA”: Thank you, Walter.

ISAACSON: Your new book, “The Bomber Mafia,” is just terrific. It’s a wonderful narrative. But start by explaining to us who were the Bomber

Mafia?

GLADWELL: The Bomber Mafia were a small band of renegade pilots in Central Alabama in the 1930s who fell in love with bombers and with the potential

of the bomber, which was kind of invention of that era to revolutionize warfare. And they bring this kind of outrageous set of idealistic notions

about how you can fight a war without leaving millions of people dead. They bring that into the Second World War. And my book is all about the story of

how this kind of dream meets reality when we actually go to war in the 1940s.

ISAACSON: And you said that it was a tale that connected with your own personal obsessions, you know, growing up in England, hearing about the

blitz.

GLADWELL: Well, my — you know, my father grew up in Kent, south of London, which was known as “Bomb Alley.” It was — when the German bombers

flew in to — from Germany to London to bomb London during the blitz, they flew over my father’s little town called Sevenoaks. And as a child, he

would hide under the bed, he would be instructed to sleep under his bed. That’s his — that was their idea of safety back then.

And at one point, even a German bomb landed in my grandparent’s backyard. And so — it didn’t explode, thankfully. So, I grew up with my father was

of that generation where the Second World War loomed large in his imagination. And I grew up on these stories of, you know, hearing the

German bombers overhead and, you know, picking strawberries with my grandmother one day and all of a sudden, a bomb attack happens and they

have to hide out in some forest. I mean, that was my father’s childhood.

So, I’ve been — you know, the way you carry these things with you your whole life and then I finally got a chance to tell a story about that era.

ISAACSON: And the bombing in England then was the blitz. It was just area bombing. The Germans were trying the demoralize England during the war. But

your book is about precision bombing. How did that come to be?

GLADWELL: So, the way you bombed in the 30s and early 40s was the physics problem of trying to drop a bomb with any degree of accuracy was so

overwhelming that people just didn’t even try. So, you if think about it, you’re flying a plane six miles in the air at 200 some odd miles an hour

and you’re trying to drop a relatively small bomb to hit target on the ground that might be quite small itself. That — doing that with any degree

of accuracy at that point in history was basically impossible.

So, most air forces just gave up and they just said, you know what we’ll do is we’ll just drop hundreds of bombs and hope something comes close. We’ll

just destroy anything we can, right. The bar mafia were convinced they could solve the physics problem. So, they thought, oh, actually, we think

we can target a bridge or an aqueduct or a powerplant and actually hit it from 20,000 feet. And they said, as a result, because we think we can

achieve accuracy, we don’t have to do this kind of wholesale area bombing that was very much the vogue of the moment. We can do — we can conduct war

on a much more humane and precise and surgical basis. That was the dream they had.

ISAACSON: And they wanted to do that for moral reasons after World War I slaughter of millions of people or was it because there was a better way to

win a war?

GLADWELL: It was both, but I think it was really moral reasons. I mean, you know, anyone who emerged in the generation after the First World War

was so chasten (ph) and traumatized by the wholesale slaughter and stupidity of that conflict, but they were determined not to repeat it.

And the Bomber Mafia were a group of people who I really think — one of the reasons that I find themselves fascinating is they are technologists,

they’re innovators but their primary driver is moral. I mean, it’s as if Mark Zuckerberg went to seminary before he started Facebook. I mean, that’s

the kind of way to understand these men. They were all men. They really, really, really wanted to find a way to fight a war without destroying half

of Europe and without obliterating an entire generation.

ISAACSON: And the technology was a guy named Carl Norden, who, in your book, sounds really weird, but he’s able to invent a piece of technology

that could enable this, right?

GLADWELL: Norden is this crazy Dutch engineer who invents an analog computer in the 1930s. You know, a kind of 55-pound mechanical device with

pulleys and gyroscopes and all manner of like and he feeds all these, you know, with knobs and levers and his idea is that you enter in every

possible variable that would make a difference in a trajectory of a bomb.

And you entered into this analog computer and it will tell you when to release the bomb. And having produced this thing, an enormous cost by the

way, the U.S. military spends — the only thing they spend more on over the Second — in the Second World War is the Manhattan Project and the B-29

Bomber. This is the third most expensive project of the war, building these little 55-pound analog computers. They put one of these in every plane,

every bomber that flies over Japan and Europe has one of these devices in it with someone who — a bombardier who spent six months training how to

use it.

And the idea was that this device will allow us to forego all of this crazy carpet bombing that everyone else was doing and just go in over Berlin,

take out the Reichsta, a couple of power plants and the railway station and then the Germans will be done. That was the idea.

ISAACSON: And there are two characters in your book who represent the polar opposites in this philosophy. So, let’s start with Haywood Hansell.

GLADWELL: Haywood Hansel is part of a long line of southern military gentleman. You know, his forebears fought in the Revolutionary War and then

were generals and in the Civil War on the Confederate side. And he is that kind of, you know, southern romantic intellectual. He writes poetry. He

sings Broadway tunes to his men when he — as he’s flying back, you know, over a bombing run over Europe. His favorite novel is Don Quixote and he

identifies with, you know, the knight who — the gallant knight who tilts at windmills. He — and he thinks of the — he thinks of what he’s trying

to do with the Bomber Mafia is part of a grand and moral crusade to reform war, and that’s his principal motivation.

His great antagonists Curtis LeMay and Curtis LeMay is the antithesis of Hansel. He is a kind of working-class kid from Columbus Ohio with — looks

like a bulldog with a big square head and a cigar in his mouth. A man of almost — to say he’s a man of few words, I think is an overstatement. And

he is the most unsentimental bloodthirsty ruthless ferocious warrior perhaps of any on the allied side during the Second World War. And he is a

brilliant, an absolutely brilliant aviator, one of the great aviators of his generation. But he finds everything Haywood Hansel stands for, be — I,

mean ludicrous does not quite describe LeMay’s attitude. He looks on what Haywood Hansel is peddling with complete contempt.

ISAACSON: And so, Curtis LeMay believes in the carpet-bombing strategy, of just bombing, as of one point, he’s quoted to saying about Vietnam back to

the Stone Age if we’re going to win a war. When did — and so, I assumed, as I started reading this book, that he’s going to be the villain in the

book. When did you get into the revisionist history mindset to think maybe he’s not the villain?

GLADWELL: Well, you know, I didn’t want to write a book with villains and heroes because if you — I think — particularly in a period of history as

complicated as this one, you can’t pick a villain and a hero. You — I think you have to acknowledge the insanely complicated decisions and

circumstances that everyone involved faced. And you have to respect the path that led to their decisions.

And much as I — part of me is filled with revulsion at Curtis LeMay. Curtis LeMay was — you know, there’s a point in the book when I list the

people in the 20th century who killed the most civilians, responsible for the deaths of the most civilians. Stalin is at one. Mao is a two. Hitler is

three. Pol Pot is four. And Curtis LeMay is 5.

Curtis LeMay — I mean, he’s in the pantheon of the most, you know, horrendous mass murderers in history. In the Summer of 1945, he threw his –

– he launches a fire-bombing campaign over Japan that results in the deaths — result in burning to death someone close to a million Japanese

civilians. And yet, you can make an argument, a compelling argument that he had no choice and that by virtue of this attack, the end of the war was

sufficiently accelerated that we avoided a much worse calamity.

ISAACSON: Now, before he’s in charge of the air campaign over Japan Haywood Hansel is. And he tries his approach first. Why didn’t — why

wasn’t that better, a precision bombing campaign?

GLADWELL: The Bomber Mafia, as so many innovators do, had a kind of idealized notion of how their technology would be used in real life. Japan

had something that no one in have period was aware of, which was they had the jet stream, which was we now are very familiar with this, but a

metrological phenomenon then unknown which was that once you get up to 20,000 feet at certain points of the year, over many parts of the world but

particularly Japan, there are winds blowing at 200 plus miles an hour.

Now, try and drop a bomb with any accuracy of a plane when it’s being blown sideways at 20 miles an hour, it’s impossible. So, Hansel tries this

strategy over and over again in the fall of 1944. He tries to do this humane surgical precision bombing of Japan and he doesn’t hit anything. And

finally, the brass back in Washington threw out their hands and say, this – – it’s it. That’s it. We’re done with this experiment. We’re going to go back and do it the old brutal way. And they bring in Curtis LeMay.

ISAACSON: And so, they bring in Curtis LeMay, they decide to do it in the old brutal way and they’ve invented something called napalm. Explain how

that was years over the wooden houses of Tokyo.

GLADWELL: Napalm — we always think about napalm in connection with the Vietnam War. But, in fact, was used, first of all, very liberally in Korean

War but even more so, it was used in a Second World War. It was designed in a chemistry lab at Harvard University in the early 1940s with the explicit

purpose of burning down Japanese houses.

So, Japanese cities in those — in that era were — the houses were almost all made out of wood and tar paper and they were very close together and

the roads are very, very narrow and so the cities were tinderboxes.

It was quite different, by the way, than European cities of that era, which were bricks and mortar, stone with lots of parks and wide streets, very

hard to burn that kind of thing down. And it had never really been used on a grand scale until Curtis LeMay decides to deploy it at unimaginable

levels over Japan in the spring and summer of ’45. And he drops tons of napalm on 66 Japanese cities and burns, like I said, close to a million

Japanese civilians alive over the course of that summer.

ISAACSON: It’s the most brutal scene of any book I’ve read in a long time. The longest night of the war, the napalm bombing, the firebombing of all

these cities, it caused me to be — you know, I was revolted by it. But behind me, you can see my cabinet here, a picture of my father that spring

when he and six friends from Tulane enlisted because they joined the Navy right then so that wouldn’t miss World War II.

I realized after I was repulsed by that chapter that had that not happened, maybe my father would have had to be part of the landing in Japan. So, how

do we morally sort this out?

GLADWELL: I don’t know if we can, Walter. I mean, what you’re describing is the calculus that was made at the time, it has been made ever since,

which was we need to bring the Japanese to the point of capitulation. And we had several options. One was to burn their cities down with napalm. The

other option was, in November of 1945, to launch a ground invasion.

Would a ground invasion have been a bloodier scenario than bombing them from the skies? Most people think yes. Most people think that your father

and his friends would probably have perished in a ground invasion of Japan. It would have been a bloodbath.

God knows how many American soldiers would have died in that and how many Japanese soldiers would have died and Japanese civilians, not to mention,

you know, the plan was to blockade Japan. So, you’re looking at God knows how many hundreds of thousands or millions of people dying of starvation.

So, what we were trying to do is overt what was believed to be a far greater nightmare, which is a prolonged endgame in Japan into 1946. And I

find the logic of that persuasive. In other words, I think we were probably correct to keep your father out of that stage of the war.

ISAACSON: All of your books, all of your podcasts, all of your vision is history’s a very good narrative. But also at the end, I realized there are

parables. They’re about something a little bit larger. This book seems to be a parable for technology, right?

GLADWELL: I thought the story was very contemporary in a sense of what the Bomber Mafia were going through was what we now go through all the time,

which was a group of people were possessed of a very, very disruptive innovation and they had a dream about how it should be used in the world.

And then it didn’t quite work out the way they hoped.

You know, I can give a million examples. You know, there was a moment, I remember, 10 years ago when we were convinced that Twitter was going to be

an agent of democratic reform in the Middle East. I mean, honest, serious people were going around saying Twitter is going to bring democracy to this

land of tyrants. I mean, couldn’t anything in retrospect seem more absurd? But that’s what we believe because we’re in that moment. So, what — this

is this story is a kind of dress rehearsal for what will go on over the next 100 years

ISAACSON: Malcolm Gladwell, thank you for joining us.

GLADWELL: Thank you, Walter.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And finally, tonight, anyone in need of an adrenaline boost? Relax you’re in luck. You could now visit the world’s longest and scariest

and most stomach-churning pedestrian suspension bridge. It’s in our Arouca, northern Portugal, at half a kilometer long and 175 meters above the fast-

flowing pave a Paiva River, walking this bridge requires nerves of steel. It’s nestled in the lush mountains of UNESCO’s Arouca Geo park. Officials

hope the attraction will give the economy a much-needed boost after the pandemic. But with the bridge wobbling a little with every step, just don’t

look down.

And finally, coming up tomorrow, Anthony Bourdain’s last book. We will speak with the woman he called his lieutenant, Laurie Woolever, about

finishing the project after his death. It’s called “World Travel: An Irreverent Guide.”

That’s it for now. You can always catch us online, on our podcast and across social media. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.