Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.”

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR (voice-over): The victims of violence.

Israeli Robi Damelin and Palestinian Bassam Aramin share their devastating stories of losing a child and why they are working together for peace.

Then:

MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY, ACTOR: Come on.

AMANPOUR: Megastar Matthew McConaughey takes his talents off screen and on to paper, writing “Greenlights,” a collection of personal stories.

Plus:

JORY FLEMING, AUTHOR, “HOW TO BE HUMAN: AN AUTISTIC MAN’S GUIDE TO LIFE”: I see value in myself, and I hope others see value in me.

AMANPOUR: Rhodes Scholar Jory Fleming gives Walter Isaacson a glimpse into his mind with his new book, “How to Be Human: An Autistic Man’s Guide to

Life.”

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

As international mediators keep trying to figure out a way to end the surging Middle East war, Israeli airstrikes and Hamas rocket fire continue

to volley back and forth, and the death toll keeps climbing.

Israel says eight of its citizens are now dead, including a child, while Palestinian officials say at least 122 of their people have been killed in

Gaza, including 31 children.

Here’s correspondent Arwa Damon on the heavy loss of life amongst the very youngest in that blockaded Gaza Strip.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

ARWA DAMON, CNN CORRESPONDENT (voice-over): A sister unable to comprehend the loss, a father gripped by gut-wrenching pain, a family unable to

understand why. Why did 11-year-old Hussein Hamad have to die?

A Palestinian children’s rights organization says the cause of death is unclear. There were both rockets being fired and warplanes overhead. The

Health Ministry in Gaza says it was an airstrike. In the family’s mind, there is no doubt.

“Why did you have to kill him?” his uncle asks. “They kill and there is no one to make them answer for it. The whole world is watching.”

How can the adults unable to cope with their own sorrow wipe the tears of the children and reassure them that everything will be all right, that this

too shall pass?

Loss like this, it never does. Two-year-old Yazan dead, along with two siblings and a young cousin, Ibrahim Hasanein also dead, Hamada and Al-

Amoor, the growing list of children forever gone.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: The terrified look on the faces of children.

That heartbreaking report from Arwa Damon.

And this violence, and international officials are calling on Israel to lift its blockade for humanitarian assistance into Gaza. The unrest is

happening outside of Gaza as well. Violence has erupted in some mixed cities inside Israel between Arab and Jewish neighbors. And clashes have

now spread to the occupied West Bank.

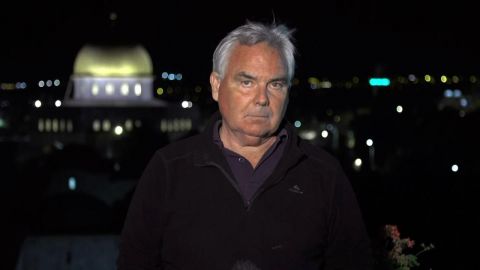

Our Ben Wedeman was there all day, and joins us now from Jerusalem.

Ben, thanks for coming back to the program.

You have been witnessing the clashes between Palestinian protesters and Israeli soldiers in Bethlehem. You’re back now in Jerusalem. Give us a

sense of how you see this spreading.

BEN WEDEMAN, CNN SENIOR INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: Well, this is — in a sense, it was inevitable, because it’s a powder keg here.

Oftentimes, you will have — for instance, there was the war of 2014 between Gaza and Israel. And it was destructive. It was horrific in terms

of human loss. And then you had seven years of, I’m not going to say calm, but compared to what we’re seeing now, it was relatively calm.

And now it has erupted again in violence between Gaza and Israel, in Israel proper, and now on the West Bank. Today, on the West Bank, what we saw was

only Bethlehem, where we were, but there were clashes and protests and confrontations throughout the West Bank. And according to the Palestinian

Ministry of Health, the death toll today alone among Palestinians was at least 10, with more than 500 people wounded.

We have not seen those numbers in the West Bank since the second intifada. And what’s interesting, Christiane, is that, a few days ago, when you had

this outbreak of communal violence between Israeli Palestinians and Israeli Jews, the government in Israel decided to redeploy some of the border

police, who normally are in the occupied West Bank, to Israeli towns and cities.

And now you see that the situation in the West Bank has suddenly ignited as well. And this really underscores just how deep the problems here are.

Now, the Israeli government over the years has tried to wall in the Palestinians, wall out the Palestinians, has tried to put down protests

violently. But it’s the cycle that goes on and on again.

And I was mentioning to some of our colleagues earlier today that being, somewhat advanced in years, as I am, I probably covered the fathers of the

young men who are now throwing stones in Jerusalem — in Bethlehem, and the fathers of the soldiers who are firing at the Palestinian protesters.

And just imagine how it is if you are a Palestinian or Israeli grandfather, knowing that your son and probably your grandson are going to be stuck in

this endless conflict with, at the moment, no sign of any sort of diplomatic out, any sort of resolution of this century-old conflict —

Christiane.

AMANPOUR: Yes. I mean, Ben, I hear you. And it just brings me back to reporting on some of that there as well.

But I want to ask you what you think is going to happen, because tomorrow is what the Palestinians called Nakba, their what they call catastrophe,

losing in the 1948 war, losing territory. There’s a big Jewish holiday as well coming up this weekend.

Do you imagine that this is going to create more of this violence and be yet another flash point?

WEDEMAN: It’s — the situation is highly flammable. Just remember this.

The funerals for the at least 10 people who died — who were killed today will happen tomorrow, in addition to the commemorations that are coming up.

And, of course, funerals, as you know, Christiane, having covered them, are followed by protests. And the protests oftentimes go to those flash points

on the West Bank.

So, put it all together, and it is a grim picture looking into tomorrow — Christiane.

AMANPOUR: Indeed, Ben.

And I’m also mindful of how much of a political vacuum there is as well. So, thank you. We will continue to be watching, of course.

Now, the long-held idea of peace and a two-state solution for Israel and the Palestinians seems like a distant mirage right now, but talk to people

who have also suffered the consequences of this war, and you will see that there still is a constituency for peace.

Robi Damelin lost her son David to a Palestinian sniper while he served in the Israeli army. And Bassam Aramin lost his daughter, Abir, when she was

10 years old, shot with a rubber bullet by Israeli border police.

And yet they have rejected revenge, and they have chosen instead to join in spreading the message that enemies must talk to each other, or else, as we

see, the cycle of violence will continue. And they both belong to The Parents Circle – Families Forum, which is a peace organization for Israeli

and Palestinian families who’ve lost loved ones in this conflict.

So, welcome, both of you, to the program.

I obviously have to ask you both, as people who believe in peace and peace activists, what you both make of this massive escalation that we’re

reporting on and that we have seen.

Robi, what do you make of this?

ROBI DAMELIN, THE PARENTS CIRCLE – FAMILIES FORUM: It’s so heartbreaking, because it’s a cycle of violence that leads absolutely nowhere.

So, there will be a cease-fire in a couple of days. And we have destroyed so many buildings in Gaza, and children in Sderot wetting their beds at the

age of 10. And mothers in Gaza have nowhere to run to a shelter.

And a mother in Sderot might have 15 seconds to get to her shelter, when she has three children and one in a wheelchair. Who should she choose?

So, what is this all for? What is this going to bring? We have to recognize that the cycle of violence must stop at some point.

I know that when the soldiers came to tell me that David had been killed, he was in the reserves. The first thing I said is, you may not kill anybody

in the name of my child.

And if I can do anything on this wonderful program of yours, it’s to ask mothers, keep your children inside tomorrow morning at the funerals. Don’t

let them go out and throw stones. They don’t understand what they leave behind. They don’t understand the pain that is caused by their loss.

And they think they’re invincible. And so I’m sitting here in my safe room in Jaffa. And I’m looking around me. And I realize there will be a cease-

fire. But I also realize that we are faced with a huge problem now internally, which can’t be solved by cease-fire. It has to be solved by a

completely different method, by a different way of working with children and educating, by giving hope to young men.

Because if you look at who is involved in all of this clash that’s going on inside of Israel, it’s young kids aged 16 to 20. And it’s the secular

children…

AMANPOUR: Right.

DAMELIN: … who feel that they are allowed to do whatever they like, and not get punished.

And so this is so…

AMANPOUR: Well, then let me ask…

(CROSSTALK)

DAMELIN: … so heartbreaking.

AMANPOUR: Yes. I’m going to get back to you in a second.

But I want to ask Bassam as well, because, as you said, you’re in Jaffa, the port city in Israel.

Bassam, you’re in Jericho, much closer to the Jordan River on the occupied West Bank. You have seen this spread. You have also lost a child, just as

Robi’s child, during the height of the last round of conflict.

What — I mean, can you see, as a peace activist, a way back to some kind of political discussions?

BASSAM ARAMIN, THE PARENTS CIRCLE – FAMILIES FORUM: Just first, I want to say, for one hour, we lost — like, my neighbor, he’s 23 years old, in the

juncture of Jericho.

He come back from his car as curiosity, a few seconds. He got a bullet in his chest, and he died. It’s very sad.

I just want to answer this question by saying that the Palestinians didn’t kill six million Israelis, and the Israelis didn’t kill six million

Palestinians here. And there is a German ambassador in Tel Aviv. And there is an Israeli ambassador in Berlin.

Just we need some brave leader who look forward, and not to keep us stuck in the very painful past, to keep the people as two bereaved people, two

bereaved victims. The Israelis claim that they are the biggest victim in history. We claim that we are the victim of the victim.

And this is still going on more than 100 years. We’re trying to kill each other, to defeat each other.

AMANPOUR: So…

ARAMIN: And what is the result? More blood, more pain, more victims.

AMANPOUR: So…

ARAMIN: And we arrive to the same result.

The Palestinians must be free, even if it continue for 3,000 years. So, we claim we know the result in advance. We need to talk.

AMANPOUR: So, Bassam, I’m really interested, because you were 12 years old when you started to resist the occupation. By 17 years old, you had been

arrested and sentenced to a seven-year jail term. And yet, as we know, jail can radicalize so many people.

But it had an opposite effect on you. You learn about the Holocaust. You learn Hebrew. You, I believe, befriended one of your guards. Tell me the

process you went through and what you learned.

ARAMIN: You know, it’s a matter of values. It’s very important to keep your moral values.

Even if you are going to kill, you are a moral person. In our case, you cannot blame a victim how to fight. I found myself to grow up under strange

occupation, people that you don’t know. You don’t understand their language. So you resist them.

It’s not to create a great Palestinian state. We don’t understand that. We want to be safe as kids. And for that, I talk about the new generations,

who have no attach to something called fear. They want to live free. They don’t care about Israel. They don’t care about America. They don’t care

about the rest of the world.

They want to be free and be safe. And this is the point. So, it was, as you said, jail just radicalize. You will become more determined to continue

your struggle. But we are human beings. When you discover the humanity of your enemy, he is not your enemy anymore.

But it’s a longer process. It doesn’t say to put the Palestinians in jail, they will become humans, and to bring the Israeli army in, they will become

Martin Luther King.

But we need to understand that we need to respect each other. We have the right to exist. As long as occupation continue, as I said, we will continue

to fight each other. It’s very normal.

So, unfortunately, it’s not up to the Palestinians and the Israelis. Also, we connect with the other great countries in the world, who use us.

AMANPOUR: And, Robi, you also — we said you lost your son to a Palestinian sniper in 2002. Your son, you say, was a gifted musician, he

was interested in philosophy and psychology.

He did join the reserves. He wasn’t comfortable patrolling or being on duty in the occupied territories. But he did go there, and he ended up losing

his life.

Tell me the story, but also that you do not have revenge in your heart, but the opposite.

DAMELIN: I don’t know.

I know, when David was called to serve in the occupied territories, he came to talk to me. And he said: “I don’t know what to do, because, if I don’t

go, what will happen to my students?”

He was teaching philosophy to kids who were going to be inducted into the army. “And if I don’t go, what will happen to my soldiers?” because he was

the officer. “And if I do go, I will treat people with dignity, and so will all my soldiers.”

And so, you see, we don’t know who the person is behind the gun. David had signed the paper to say, with all the officers, that he wouldn’t serve in

the occupied territories. And he was in this dilemma.

I think very much that my South African background had a lot of influence on what happened to me when I heard that David had been killed. And I knew

from the beginning, just as Bassam says, that one Palestinian killed my child, not the whole nation.

And, by the way, he didn’t kill David because he was David. If he had known him, he could never have done so. He killed him because he was wearing a

uniform in an occupied territory.

That’s hard to say, but that’s the truth. And I believe with all my heart that, if we do not find a framework for reconciliation to be an integral

part of any political future agreement, all we will have is a cease-fire until the next time.

And that is the work that we do in The Parents Circle. And, in fact, what happened, after David was killed, I was giving a talk at the American

Embassy in Tel Aviv. And a Palestinian came to talk to me.

And he said: “I just want to tell you that the day before your son was killed, he — I drove through the checkpoint, and he came to the car. And

he said: ‘I have to look at your papers. I promise you, I will do it as fast as possible.'”

And they had a long conversation. And he said: “The next day, when I heard your son was killed, I was so sorry.”

You see, he saw the humanity in each other. And that is the essence of all the work that we do in The Parents Circle, is this allowing a person to

talk. And it doesn’t matter if you don’t agree, but you can have empathy.

And let me tell you that there are so many thousands and thousands and thousands of families all over the world now who have lost. And if they

would harness that pain to make a difference in their communities, it will give them a reason to get out of bed in the morning, because that’s what

keeps me going for so many years of slogging it out and never giving up.

And we cannot give up. I look into my children and my grandchildren’s eyes, and I know that this is what I have to do.

AMANPOUR: And you even wrote to the parents of the sniper who killed your son and explained this to them.

And I’m going to get your — talk to you a little bit about that in a moment.

But I want to ask Bassam then the same, because a couple of years after — or about five years after Robi lost her son, your 10-year-old daughter was

killed, I believe, by a rubber bullet, I believe by a border — Israeli border police there.

How did you deal with that? How did that challenge your desire to be still on the side of the peace camp?

ARAMIN: In fact, two years before this tragedy, I was a co-founder of a group, Combatants For Peace, which is (AUDIO GAP) occupation with (AUDIO

GAP) freedom fighters (AUDIO GAP).

And we…

AMANPOUR: I’m going to come back to you, Bassam, once we get your audio. We have got some bad technical issues, but we’re going to get your audio

back.

Robi, let me ask you why you decided to write to the killers, the parents of the man who killed your son. And have you heard back from them? What

were you trying to say to them?

DAMELIN: Look, I knew — when I didn’t know who had killed David, I was very busy running around the world talking about peace and reconciliation.

And I thought that was really very, very, very important. I spoke in Congress and in the House of Lords, and you name it.

And one night, I was sitting at my desk, and there was a knock on my door, and there were three soldiers outside. And when I opened the door, and I

saw three soldiers, I slammed it in their face. And I said: “I cannot lose another child.”

And then I opened the door. And they said: “We have come to tell you that we caught the man that killed David.”

And that was when it became almost impossible. How could I do this work in integrity if I wasn’t willing to walk the talk? And so it took me months.

And, eventually, I wrote a letter to the parents of Ta’er. That’s name of the man who killed David. I told him all about David. I told him about The

Parents Circle, that we were more than 600 families who have dedicated our lives now and have gone through transformation, and want to seek

reconciliation and save our other children, and that we should meet.

We owed it to each other. That’s — that probably is my South African background.

Well, it took something like three years until I got an answer. And he told me that I was crazy and that I should stay away from his family.

And then we went to South Africa to make a film about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and to see what lessons we could learn for Israel

and Palestine. And, for me personally, this was a trip to investigate what I mean when I say that I forgive.

And I met this extraordinary woman there who had lost her daughter. She was white and African. And you could give her a label and say that she was pro-

apartheid. But she had gone to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. And she said to the people who killed her daughter, “I forgive you.”

And I wanted to know what she meant. And I went to meet her. And she said: “Forgiving is giving up your just right to revenge.”

And then I met the man who sent the people to kill her daughter. And he said: “By her forgiving me, she has released me from the prison of my

inhumanity.”

And then I came back. And this is a very long story. And I wanted to meet the sniper. And I got permission from Tzipi Livni, who was then the

minister of justice. But then we had elections. You have noticed that we have rather a lot of elections.

AMANPOUR: OK.

DAMELIN: And I couldn’t do that.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

DAMELIN: But it’s waiting.

AMANPOUR: I think we have — it’s really profound story, Robi.

Just listening to the both of you speak, it’s almost like we’re on a different planet, when we see what the — what’s happening on the ground

right now.

So, we have Bassam’s audio back.

And I just want to ask you just a final question to comment. You have written, Bassam, that: “It was one Israeli soldier who shot my daughter,

but it was 100 former Israeli soldiers who built a garden in her name at the school where she was murdered.”

Do you still have hope? And what would you say to your own leadership and to the Israeli leadership, if you could, right now?

ARAMIN: It’s not a matter of hope, Christiane. It’s a matter of faith.

We’re not going to live under this occupation forever. We’re not going to kill each other forever. And we are going with our life — the life circle

of history.

So, I believe, in one day, we will have peace agreement, we will live in peace. We are not going to disappear. We’re not going to — like, we forget

to die, in fact. So we have — we will exist, both of us, but how much blood we need?

And you can imagine that I’m afraid that history will repeat itself when I see and hear about red marks on the Palestinian houses inside Israel, which

very scary, remind me with the ’30s in the last century.

To see Gaza, it’s unbelievable. It remind me with the two towers in New York, September 11, against civilians, and the fear on the other side. We

cannot live a normal life in these circumstances, because, again — it’s very simple — the occupation is the source of this terrorism and madness

in both sides.

If there is no occupation, we don’t need to kill each other. We don’t need to fight each other. So, I say to the — to our leaders…

AMANPOUR: Well, we appreciate…

ARAMIN: In fact, I want to tell you, the Americans…

AMANPOUR: We appreciate the message. Yes.

ARAMIN: One sentence.

We cannot breathe. Please.

AMANPOUR: Yes, that is the George Floyd line, isn’t it?

Bassam Aramin, Robi, thank you so much, Robi Damelin. Thank you both so much from Israel and from the occupied territories to talk to us about

peace today and about basic humanity.

Next, I speak to the Oscar-winning actor and producer Matthew McConaughey. He’s risen to Hollywood stardom, of course, in romantic comedies, before he

pivoted to heftier roles, starring in blockbuster hits like “Interstellar,” “The Wolf of Wall Street,” and “True Detective.”

Now he’s put pen to paper, as he raids decades of his diaries for his frank memoir “Greenlights.”

And Matthew McConaughey is joining me now from his home in Austin, Texas.

Welcome to our program, Matthew McConaughey.

So, let me start by asking you, why “Greenlights,” all one word? What does that mean?

MCCONAUGHEY: Yes. Before we jump to that, can we just take a moment?

I have been listening to that last — your last interview with Bassam and Robi.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

MCCONAUGHEY: And, whoa, you said it after it, but how about that as an example of — talk about humanity and the courage of grace and forgiveness

and the value of keeping moral values?

You can discover humanity in your enemies, and there is the road to making enemies no more, and the value of, we have got a responsibility of being

better parents. Ah, wow. I just want to take a moment there, because that – – what they said, we need to move all of our floors.

AMANPOUR: Yes. I’m really pleased that you listened. And I’m pleased that you’re reacting, because this story that we’re reporting on — and you have

heard our reporters, and you see it all over your airways now in the United States — somehow lacks the human touch when we report it.

It’s always about the politics and about the firepower and about the extremes. So, it’s so important that we can concentrate on what really

matters right now.

So, let me just get right to it, then…

MCCONAUGHEY: Yes.

AMANPOUR: … because you have obviously connected with Bassam and Robi, and the fact that they lost their children. Each one lost a child.

And I listened in preparation for this interview to one of your commencement speeches. And you said that you had five main objectives and

important rules in life. And the first one was fatherhood and husbandhood. And then it went on to friendships and faith and the rest.

So, talk to me about fatherhood, and what that means to you in the context of your life today, yourself as a son and yourself as a father?

MCCONAUGHEY: Yes.

Well, when we have children, we literally become immortal. And there’s great humility in that, and we get more courageous. I know I have. And, as

Bassam and Robi were talking about, she said she gets out of bed each day and keeps persisting for her children and grandchildren.

I’m — you have children, you start making — for me, I start making legacy choices, choices that — where I can spend my time, where I can maybe give

my talent to things that are going to outlive me, to things that — immortal finish lines, I think, are the things that we start to see when we

become a parent.

There’s things I know that I have started to see and try to live for, legacy things that I can leave behind. They’re going to be the truest

extension of me and their mother in the world after we’re gone, hopefully.

So, what things can I build now? What kind of man can I be now that will live on through my children long after me and hopefully generations after

them?

AMANPOUR: You have been thinking a lot about that. And your book is very clear about many of those issues.

And it starts with your parents and their love through their fighting and what you learned. So, I am interested in that, because, when you basically

said — and they had sort of knock-down, drag-out fights, but they were desperately in love. They got married and divorced a couple of times. And

yet you said that…

MCCONAUGHEY: To each other.

AMANPOUR: … you learned about love, not from you — to each other is what I meant. Sorry.

You learned about love from them, but not necessarily from the hugs, but from the fighting. And I’m interested in that.

MCCONAUGHEY: Yes.

AMANPOUR: What did you learn from the fighting? Why did that give you hope?

MCCONAUGHEY: Yes, it’s a great question. And I have been asked it many times, because when I talk about the love that our family had, the love

stories I tell are the ones that I shared in the book.

There’s violence. There’s fights. Knives were pulled. Blood was dripped. And why do you tell those stories?

And I have given it a lot of thought. And I believe it’s this. Those are the times where the love was so literally challenged, you thought — you

hear those stories. I saw the fact of those stories, and you look, oh, this is where it all breaks down. This is where the story does not end well.

This is where the love falls and falters. No. It never had a chance to falter.

Like I said, the metaphor would be my mom and dad divorcing twice but marrying three times. Well, in the end, love one. Three to two. But it was

vitally challenged often but it never had chance of getting beat. And in talking about parenting, there’s one thing that us — my two brothers and I

knew was nonnegotiable was that we were loved. We heard it all the time. Hey, I love you. I just don’t like you right now. If we were out of line or

got in trouble. But the love was never in question. And it was a hard love.

There were definitely more hugs than hits in my family. Make no doubt about it. I just happen to tell those stories about sometimes when the hits were

there because that’s when the love was challenged but it never had chance of being beaten.

AMANPOUR: And you always talk about, you know, the values you learned and what you wanted to pass down. And you said that, you know, you would not

trade any of the ass whooping that you got for anything because it instilled values in you. What values in you and what values are you

therefore passing onto your children?

MCCONAUGHEY: Yes. My parents were big on don’t say can’t, don’t lie and don’t say hate and don’t believe in hate and don’t half ass it. Meaning,

when I say, you know, I wouldn’t trade any of those ass whoopings in for the values that were instilled in me, I don’t remember any of the immediate

slight pain I had from the belt or that ass whooping. What I remember is the distraught look on my dad’s face of feeling like he was failing as a

father when he gave me chance to telling the truth four times and I lied to him four times to his face. That’s what I remember.

Oh, my gosh. My father feels like — I remember clearly in my mind the look on my dad’s face feeling like distraught. What am I doing? Why haven’t I

raised a son that won’t tell me the damn truth about a damn pizza he stole? If I had told him the truth about stealing the pizza, he would have been

like, well, gosh. Buddy, I’ve stolen pizzas before as well. Now, number one, don’t do that again. Number two, if you do, get away with it better

next time, will? But I couldn’t. I was a coward. I didn’t have the courage tell him the truth.

He, you know, don’t like — don’t say hate. The first butt whooping I got was for telling my brother I hated him, and I didn’t mean it. I just heard

the damn word at school. And it was my own birthday party. And my mom stopped the birthday, told me to lean me against the wall and got me with

the switch and she says, don’t you ever hate. Don’t you ever hate.

Now, what’s the value that’s instilled for me of that? Through my life, I can look back and go, well, I kind of felt pain when I lied. Well, I don’t

like pain. So, the opposite of lie is tell the truth. Well, I kind of felt pain when I said I hated. So, what’s the option of that? Love. OK. Let’s do

that one. That brings pleasure.

AMANPOUR: Got it.

MCCONAUGHEY: So, don’t say can’t.

AMANPOUR: I got it.

MCCONAUGHEY: That was a big — you could get in trouble doing something but don’t say can’t. So, the antonyms of those words that we got in trouble

for are the values that are instilled. And the ones that I’m trying to instill on my children indifferent means in ways that my parents did but

ones that I still and trying to instill in them.

AMANPOUR: And so, let’s, you know, obviously talk about your incredible career. Look, I mean, you know, you sort of give the impression of being

kind of, you know, laid back and, let’s say, fair and dazed and confused, if I could coin a term. But your career was anything but. I mean, you

really did really focus on getting those parts. They didn’t just fall out of, you know, like manor from heaven. You weren’t just suddenly an

overnight success. You went after it. Tell us about that.

MCCONAUGHEY: Well, I think I am much more intentional than I think people perceive stereotypical me to be. I can find a way I intentionally chase

something down with every role I ever got. I hustled in both senses of the word throughout my career. I took advantages of things when I could and

opportunities and places and people. Yes, some great fortune fell into my lap. Hopefully, I did everything I could with it when I did.

I also — a big hinge point in my career was about 15 years ago after I was such a success with romantic comedy lead. I’ve been so successful in

romantic comedies that the dramas I wanted to do were not being offered to me because Hollywood was saying, no, you stay in your zone, Matthew

McConaughey. You’re a rom-com guy. So, when I couldn’t do what I wanted to do, I stopped doing what I had been doing, which was the rom-com.

Now, that was me buying a one-way ticket into limbo and maybe never working in Hollywood again. And — but I chose to make the sacrifice and it was a

sacrifice. I didn’t get work — I didn’t work for over two years. Hollywood forgot me.

Now, what happened when Hollywood finally forgot me, when they didn’t see me in a rom-com or the theater or in their living room or didn’t see me

shirtless on the beach for two straight years, it was all of a sudden, I found some anonymity again. I had unbranded. And all of a sudden, Hollywood

called again and said, you know, what would be a novel good idea for “Mud,” “Killer Joe,” “Paper Boy,” “Magic Mike,” “True Detective,” “Dallas Buyers

Club,” Matthew McConaughey. Those were the dramas that I wanted to bore (ph). When they came, I just — I latched onto them with long fangs and got

after it.

AMANPOUR: Can play a little clip?

MCCONAUGHEY: But it took that — like a rebrand.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And that’s an intentional and quite brave thing to do, frankly. I want to play a little clip from “Wolf of Wall Street” because

it’s iconic.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MCCONAUGHEY: We’re the common denominator. Keep it up on me. You see me at a wall, how the money comes in.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, you’re doing it now as we’re watching the clip. That wasn’t scripted, was it? Just what happened? How did that get into the film?

MCCONAUGHEY: So, look, banging on my chest to some tune, I have music and rhythms for every scene that I’m in for every character that I play and

every movie. They’re different for each scene. That was the rhythm for Mark Hanna, that character, that I’ll do before the scene. It is to get out of

mind, to relax, to bring the voice down, to find my musical meter with the character in the scene, because I think in musical terms a lot.

Now, I’m doing that before the scene and then action is called. I stop and we begin the scene. Well, we did about four takes that didn’t have that in

it, but before the take I was doing that in it. And we had it. I was happy. Martin Scorsese was happy and Leonardo was happy. We were moving on. Wrap.

That’s it. You got it. Well, Leonardo raises his hand and says, hang on a second, Martin. He leans over and he goes, what’s that thing you’re going

before each take. And I told him what I just told you. He goes, why don’t you put that in the scene? I was like, great. And what you see there is the

next take.

And so, I started off in the scene, I did it. And then I went into my dialogue and with Leonardo’s character and then we got to end of the

dialogue and I figured I’d pick the beat back up which would sort of bookend the rhythm and it would be like, OK, does the young man understand

if he can get on frequency with (INAUDIBLE) as my rhythm here again, that means he gets it. And it was sort of — the last doing it at end of the

scene was sort of the affirmation or the confirmation that I’m getting from the character that Leonardo is playing that he understood my pitch.

AMANPOUR: Well, it’s a marvelous story and very indicative of how you work and who you are. And thank you for being with us. Matthew McConaughey, now

author of “Green Lights.”

Now, we get an insight into life with autism. Jory Fleming first made headlines as the University of South Carolina student with near perfect

grades. And he has just completed his masters at Oxford University where he was a Rhodes scholar.

His new book is “How to Be Human: An Autistic Man’s Guide to Life.” And here he is speaking to Walter Isaacson.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane. And, Jory, welcome to the show.

JORY FLEMING, AUTHOR, “HOW TO BE HUMAN: AN AUTISTIC MAN’S GUIDE TO LIFE”: Thank you, Walter. It’s great to meet you.

ISAACSON: You’ve written an absolutely beautiful book in which you dig inside your autistic brain to show people what’s hidden. So, tell me how

your brain is different from a typical human brain.

FLEMING: Yes. And, you know, it’s sort of — it’s hard to pin down sometimes because I’d always feel like there’s a sense where it’s difficult

for me to peer into somebody else’s brain. But some of the things that I have noticed are maybe most familiar to people watching like difficulties

with language, difficulty in understanding all of the subtle nuances that come into how people communicate whether that’s body language, whether

that’s their movement with their different various body parts in which there are many to have to keep track of, whether it’s the intonation of

which they speak.

So, not just the words themselves but actually which words they select, the order they select and how they are sounded out. All of that is highly

relevant to nuance conversation. And that’s really not something that I’m not great at.

But there are other aspects of my brain that have been a great benefit to me. And I think these, for me, included the fact that I consider myself

quite a visual thinker, whether it’s my memory that I think has some benefits and abilities, I guess, and surprisingly so in reaching far back

and in bringing up things that are relevant from my past or from past knowledge.

ISAACSON: You said that you’re a visual thinker, does that mean you don’t think in words?

FLEMING: Yes. So, one of the things that I was excited to communicate with the book was how language is something that is almost foreign to me and

that’s because, as you were indicating with your question, you know, I really don’t have words in my brain at all. I consider them really linear

and my brain is, you know, just not very linear. It’s just wired differently I opposed. So, I definitely don’t have any words at all or

language at all in my brain. I have plenty of other stuff, especially visual images, also sounds, experiences, sort of flashes of memory, all

sorts of different things, but I definitely know words for sure.

ISAACSON: Early on in your childhood, you were very troubled in terms of not being able to speak and having emotions that were hard to control. Tell

me how your mother helped move you down the path where eventually you go to college, went to Rhodes Scholarship, go to Worcester College, Oxford and do

all these amazing things.

FLEMING: Yes. You know, my mother has played a crucial role in my life. She’s been my carer, my teacher and many other things. And I think what my

relationship with my mother has made me think on is the fact that in many ways, I’m, I guess, the product of many people caring for me and helping

me. And when I was younger, I was homeschooled. And it was able — I was able to learn an environment that had less of the stimuli that often impair

my ability and cause a great sort of depletion of energy, some people might call that stress, I don’t know what you would call it exactly.

But, you know, even for this interview, I’m turning the fluorescent lights on in my office and I can hear them and it’s horrendous but I have the

capacity to do that in part because I’m excited to have a chance to speak with you. And I think that I have the energy to do that, the capacity to do

that is a direct product of my mother as well as others who’ve made an investment in me and cared about me and want to see me succeed and to be

able to, in turn, show that care for others.

ISAACSON: You talk about how when you got to college there was a manual for people who did orientation, to tell them tricks, ways that they could

engage with incoming students. And when you read it, it was actually a godsend because he was a manual on how you’re supposed to deal with other

people. Tell me how that worked.

FLEMING: This manual you know you mentioned was when I was being a teaching assistant for the first-year seminar class, and a lot of that

class is helping students navigate the transition to college, a new part of their life, a new environment, a new routine. And there was a section that

was about communication and how to have open ended communication. And a lot of that was really helpful in part because it was directing implicit. And

part because I realized it spoke to things that actually could be good at.

And one of those was the importance of listening. And for someone who has great difficulty in creating words out of the space in my mind, the fact

that I don’t have to do that and can actually have a deeper interaction with someone just by saying nothing was an amazing revelation. And I think

since that time, I’ve gotten some comments from friends and colleagues that I’m a decent listener and maybe that’s a function of reading that manual

and being able to say, oh, this is sort of a ranking or a way to sort of actualize some of that hidden context that everybody seems to know by

default.

ISAACSON: In your book I get the sense that emotions are not something that you deeply feel in the way neurotypical person would, but there are

things that you’re able to observe. I mean, you can sense and observe emotions while not feeling them. Is that right? And explain to me what

that’s like.

FLEMING: I think that comes to emotions from a different perspective. And one of the images that I use for that is if some people are in a lake, I

may be on the shore where my feet are in the water but I — mind my head. If that makes any sense. And another, I think, is a register. And, you

know, I think people — you know, when you go to the register of the store, you arrange things up and it always spits out the same amount with the

barcodes.

But what if the register could pop out different amounts when scanning the same barcode? Of course, that’s something that a register is inherently

capable of doing. But if your experience at the register as identical every time, then you may not notice that it could bring up a different thing just

with another few clicks of the keys. And I don’t know of images like that are helpful, but because that’s what my brain relies on to doing own

thinking, that’s how I try to share that with others.

ISAACSON: Most people organize and retrieve information in their heads by having narratives, by making connections between things and turning it into

a story, into a narrative. How do you organize? I mean, you have a lot of information your brain. You’re so smart. You studied geography, you know,

you have a great storage of knowledge. But how do you organize that information in your head since you don’t do it by making the narratives

that some of us do?

FLEMING: Yes. I think, you know, what you speak to is, I think the elements of story building are still in my mind but they’re not — they

don’t have to be arranged in sequence in order to make sense. And, you know, in my book I use a couple different analogies but one that is quite

visual is this concept of Jory beads (ph). And to put things into my mind, they have to be translated into my native space, my native operating

system. But once they’re there, I have the ability to use them in my space in a way that is, I guess, the opposite of linear where I sort of pause up

the beads that are relevant after I decide which ones are relevant and they’re all there.

And I can make patterns or connections between them at random or at will just in so many, and they don’t shift positions, they’re just there because

I’ve sort of truck them out of the memory vault, I guess. And yes. So, I can build stories in my mind and I can vanish them just as quickly to make

a new one, to reverse it, to make it in different directions, to split it in half, to put it in thirds, any of arbitrary division.

And some of that may be a bit of a jumble sometimes. But sometimes it can lead to moments of clarity and then I’ll latch on and go with that. You

know, I’ll translate it back if I need to into words or whatever to continue the conversation.

ISAACSON: Is there something people like myself can learn from the way you process information which is in a less emotional way but perhaps a more

logical way?

FLEMING: I think — you know, I think that — I’ve thought about this a little bit and I don’t think that just because I’m autistic that some of

the ways that I think are out of the range of other people’s brains, if that makes sense. I do think thinking about how you think is not something

that people may be doing on a daily basis. But I think everybody certainly has the ability in a capacity to take moment and say, wait a minute. I

actually do, I think.

You know, what role do words play in my mind, what role does memory play in my mind, how often do I question the output of my own thinking process if

it happens subconsciously or automatically, and whether that’s pausing to ask yourself a question, if you need to use words to do that and maybe

that’s a way to do that. But, you know, if your brain just pops something out of you automatically, you know, anybody can stop and say, OK. What —

you know, where did that came from? You know, why did I think this and not that?

ISAACSON: Oof the breathtakingly beautiful things about this book is how self-aware you teach yourself to be, you become, you understand how your

brain is really working. And one of the things I think it could do for other readers is that even those who are typical brain function, they could

become more self-aware and say, how do I think, how do I form conclusions, how do I create emotions. What tips do you think your book gives to those

of us who want to become more self-aware?

FLEMING: I think you need the desire to see the future and the past, to imagine your relationship to others in a new way. I think that at the end

of the day, you know, recognizing that everybody is unique and everybody has a story to share with others and the value of another person is

something that is so tremendous and it’s almost hard to fathom when you realize that the people you pass on street, they’re all reservoirs of value

that are equal yet distinct from each other’s reservoir that’s passing you down the street. You know, huge percent water and the remaining bit is just

a tremendous amount of value that just sort of crumped into that remaining, you know, percentage.

ISAACSON: I’ve written a book recently on genetic editing and I actually quote you in the book because one of the questions that arises is, if we

ever get the ability to edit human genes so that we could eliminate conditions such as autism, is that something we should do? What’s your

opinion?

FLEMING: Yes. I recently read your book and I don’t know. I didn’t realize that I was going to be in it. So, that was somewhat of a surprise. But I

think that, you know, I’m a very visual thinker. And so, there are many times in your book that you speak about people trying to navigate a path

forward. But, you know, if I’m on a boat with somebody else and they come up to me and they look me in the eye and say, I found a path forward, and

then they push me off the boat, I’m not a fan of that, I guess.

And what saddens me about it is less so the fact that I drowned but more so the fact that the person, whether it’s singular or plural, who decided that

didn’t see me as fully human. And, you know, there’s many complexities in the book, but I think that — and you speak to the importance of

conversations. But I really think that in order to have these conversations, in order to move forward in any meaningful way, you have to

recognize the participants in that conversation as fully human.

ISAACSON: And so, you think that the human species is better off and that if you had the choice to make again, your life is as valuable having autism

as part of it?

FLEMING: Yes. You know, I see value in myself and I hope others see value in me. And I can’t control how other people seem me, but I and share my

life, my experiences and live life, you know. To be a human in the world is something that is tremendously valuable, it’s something that I’m grateful

to have the chance to do, whether my life is long or short, whether the number of people that I meet is small or large, whether my influence on the

world is lasting or temporary, both can be positive and I want to make it positive, and I’m going to try to make it positive.

I don’t know what that means in this sort of large questions that are brought about by the science of editing genes. But, yes, I guess at the end

of the day, I’m person and I’m going to try to enter that space with the experiences and the knowledge that I have in a way that it benefits others.

ISAACSON: Jory Fleming, thank you so much for writing this book and thank you for being with us today.

FLEMING: Thank you, Walter.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And of course, we see the value of Jory. That’s it for now. You can always catch us online, on our podcast and across social media. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.