Read Transcript EXPAND

BIANNA GOLODRYGA: We’re going to continue our conversation now on trauma and we’re going to turn to Israel and Gaza. A week-long cease-fire may have

silenced the bombs but the psychological scars from the decades-long conflict remain. Hala Alyan is a Palestinian-American writer and

psychologist who focuses on the impact of generational trauma. Here she is speaking to Michel Martin about how her experience as a Palestinian abroad

has inspired her work.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

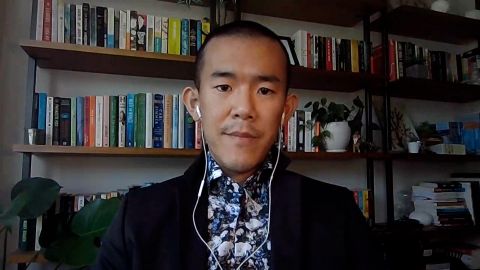

MICHEL MARTIN: Bianna, thank you. Dr. Hala Alyan, thank you so much for talking with us.

HALA ALYAN, AUTHOR, “SALT HOUSES”: Thank you for having me.

MARTIN: You are a clinical psychologist and a writer of poetry and fiction. You’ve written some remarkable and critically acclaimed work about

people of the diaspora. We are speaking a few days after the bombing of Gaza and the air strikes directed at Israel have ceased under a negotiated

cease-fire. And I’m just wondering what these last few weeks have been like for you?

ALYAN: It’s been devastating. I mean, I think it’s been devastating for all of us that are in the diaspora with the understanding and the caveat

that it in no way compares to the devastation that people on the ground are experiencing in places like Gaza, but it’s been heart wrenching, and I

think it’s also important to note that for a lot of us, we’re aware that these — you know, a lot of these policies and this oppression and this

occupation is something that’s ongoing. It’s happening. Like there’s a cease-fire right now and that’s very welcome come, but there isn’t a cease-

fire on the human rights violation, there isn’t a cease-fire on the apartheid policies. And so, I think it’s really important to kind of keep

talking about this even when there is an active bombing.

MARTIN: I want to tap into both of your identities, as we mentioned, both as a therapist and as a writer and a storyteller. Like the first thing I

wanted to ask you as a therapist, what concerns you most about what’s just happened? I mean, we know that about a dozen people were killed in Israel.

We also know that more than 200 people were killed in Gaza including 60 children that we know of at this moment. What is the effect of an

experience like this?

ALYAN: Yes, I mean, you know, I’m going to quote the Palestinian psychiatrist, Samah Jabr, who spoke really beautifully and wrote really

beautifully about this idea that the concept of PTSD stands doesn’t really apply to a lot of Palestinians. PTSD stands for post-traumatic stress

disorder. She makes the point quite effectively that there is no post for most Palestinians.

Trauma, in order to heal from trauma, one requires reprieve. And at the end of the day, the conditions that birth trauma for Palestinians endure in

periods, even the periods that the outside world considers to be cease- fires. And so, you need reprieve not just from the conditions that made the trauma that you’re in currently, but you need reprieve from future trauma.

And so, I mean, one of the things that comes to mind is the gut-wrenching story of the 11 children killed a by Israeli air strikes were actually in a

trauma program led by the Norwegian Refugee Council. So, these are children that were already being treated for trauma that were killed in their homes.

And so, when you have a situation where children who are already traumatized don’t have a sense of safety and security in their homes to

access that reprieve for healing, I mean, I think that says a lot about where we’re at in terms of trying to create the conditions for actual

recovery from trauma.

MARTIN: Part of your fiction, at least one of the books that we want to talk about today, “Salt House” is your — an award-winning novel published

in 2017, sort of deals with the experience of diaspora, of being perpetually displaced. But it also deals with the ongoing — the day-to-day

experience of living both here and there. And I’m interested in also the people in your extended network who don’t live in Gaza. How are you

experiencing this? Is this something that they can kind of — that they are living too?

ALYAN: Absolutely. I mean, I think, you know, we can have the conversation of sort of the trauma that’s experienced by folks and (INAUDIBLE), the

trauma that’s experienced by Palestinians with Israeli citizenship facing apartheid policies, the trauma that’s faced when you have Palestinian

cities that can’t access each other because of checkpoints. But there is absolutely also the trauma of erasure that you find within diaspora

communities.

There’s the trauma of — you know, I think there’s a way in which sometimes we think about diaspora as something that kind of gets nostalgic and

sanitized and its sort of like looking at the (INAUDIBLE) through a pane of glass, but the reality is that diaspora doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Diaspora

is the result of violent dispossession.

And so, I think, for a lot of us in the diaspora, as we’re watching this, we are being reminded of the fact that we are, in many ways, very much the

lucky ones. And I want to be very clear about that, right. I am in Brooklyn right now. I am relatively safe. But even to be a lucky one, still at the

tail end of a fair amount of violence and dispossession, my parents did not end up in Oklahoma because they were fans of midwestern winters. They went

there as a result of violent dispossession.

[13:35:00]

My grandfather’s — my grandparents — maternal grandparents, (INAUDIBLE), was virtually wiped out of existence, you know. And so, I think, for a lot

of folks in the diaspora, we’re watching the Senate sort of — it’s very much a reminder of what our families have already been through.

MARTIN: You know, I’ve had the privilege of interviewing a number of Native American writers and when I asked them what they most want other

people to know, very often they say that we’re still here.

ALYAN: Yes.

MARTIN: And your award-winning novel “Salt” has a centrist (ph) on the experience of a Palestinian family through four generations. Would you just

tell us a little about it for people who aren’t familiar with it?

ALYAN: So, it starts in pre-’67, in Nablus, and it centers around a family that has already been violently dispossessed from Jaffa and ended up and in

Nablus. And then post the 6th day of in ’67, they end up in Kuwait. And then, after Saddam’s invasion, which is unfortunately a story that a lot of

people in other countries are familiar, with this idea of multiple displacements. They are displaced once again. And at this point, the family

kind of becomes scattered all over the globe.

And so, the story is, like you said, over four generations, different family members speaking at different points in time and kind of, you know,

just trying to kind of have lives in the midst of diaspora.

MARTIN: We’ve only, I think, recently as just the general public started talking about how experiences even generations ago can influence you in the

present day.

ALYAN: Right.

MARTIN: I’m thinking about in your novel, “Salt Houses,” I am thinking about Salma, the matriarch, and how the decisions that she makes for her

family, for example, sending one of her daughters — or rather consenting to a marriage for one of her daughters that will send her far away saying

she knew she would be safe in Kuwait, her unhappiness, if it came, was worth the price of her life.

ALYAN: Yes.

MARTIN: Is that something that you think is a common experience of the people that you think about and write about part of your life? The sense of

constantly having to make that tradeoff?

ALYAN: I think at the end of the day, when we talk about diasporic populations — and I want to be clear. I think sometimes folks leave their

home band voluntarily, right? They leave because they’re looking for like a future. They want to study abroad and whatever. And that’s very, very

different than violent dispossession. I want to just make that distinction.

So, when speaking of the latter, you know, I think that absolutely what ends up happening is that folks within those populations are — there is

often a deeply felt sense, even if it’s several generations back of the world being flipped on its axis. And there — and this is what trauma is at

its core, right? Trauma usually kind of splits the world into pre and post, like before and after. Where — for people who have a single defining

events of trauma where there’s kind of the sense of like the world is no longer to be trusted, the world is no longer to be seen as safe.

You’re not sure even — if there are periods of stability or periods of quiet in your life, in your personal life, you’re not sure that you can

trust that. And so, that manifests, I think, in a lot of ways in hypervigilance, in a constant feeling that waiting that the other shoe is

going to drop and a constant sort of obsession with safety and how to have some semblance of control in a world that has already proven itself to be

way beyond the (INAUDIBLE) control. So, I definitely that’s something that’s true for a lot of folks.

MARTIN: Most of the book is told through the eyes of women, and they are left to internalize and imagine the horrors experienced by the men.

ALYAN: Yes.

MARTIN: There’s a horrifying scene, though, I think one of the most disturbing in the book is narrated by a man. It’s about the rape of his

sister. You are left to assume that it is by Jewish insurgents or soldiers trying to intimidate the family into leaving, but it’s described sort of

elliptically, almost as if it could be a buried memory or it could be a borrowed memory, and I was wondering why you chose to describe that scene

in that way?

ALYAN: I think that I really — as a clinical psychologist, one of the things that you often see when we talk about trauma and memory is that

trauma fragments memory that we talk about the way that people who have been traumatized or have experienced chronic trauma is that it does stuff,

it shifts something in memory.

So, you know, when you experience something traumatic, you’re (INAUDIBLE), right? And so, in some ways, the memory can be incredibly vivid and you can

remember, very, very, very specific details, but at the same time, there’s a lot of self-protected mechanisms in our ecosystems that can shut things

down. And so, you will hear people, for example, who are survivors of sexual assault talk about kind of blocking out or leaving their bodies or

sort of like disassociating.

[13:40:00]

And I think that there is this way in which I — when I write about trauma and traumatic memories through characters, and, frankly, in my own life and

my own mom fiction, I do think it’s important to thread the needle between this way in which some things are really, really, really clear and like

incredibly vivid and then also some things the system shut down to protect you.

MARTIN: We are in a really polarized moment. It’s very hard to have conversations about a lot of things in this country, as well as around the

world. And I’m wondering like how — if, in part, this was a distancing to allow people to say, maybe this happened, maybe this didn’t happen this

way, but we can still talk about it?

ALYAN: No. I mean, I — those experiences of sexual violence did happen and it’s been recorded by historians. It is very important to be able to

name experiences and put language to them. These things that happened didn’t happen to that character. That character is a fictional character

but there are (INAUDIBLE) who did happen.

MARTIN: OK. I’m just saying that I find — I think that people will find that very shocking.

ALYAN: Look, I wrote a story about a Palestinian family, and you can — I am sure you can imagine how airtight my sources had to be when I was

writing it and how carefully I had to do research and to make sure that I did not write about anything that was not documented by both the primary

and secondary sources. So, I think there’s that.

I do think it’s really important for us to all have conversations about the narratives that we have and the stories that folks get attach to. I think

that in this country, there often is — folks are exposed to certain stories and certain narratives about Palestinians, about Israel, and being

about this Israel as a government, Israel as an entity, Palestinians as a people. There’s a lot of erasure. There’s a lot of — if you look at the

media and there’s a lot of — even the depictions of like the dead are different, you know. It’s one — like people get killed versus people are

dying. There’s like — there’s a lot of analysis that’s being done right now around sort of the language use and headlines when we’re talking of

death in Palestinian communities.

There’s a lot of neutral language like clashes or war that implies parody in armies as though there are, you know, two equal armies that are in

conflict with one another. And I think it’s — listen, I have no ill will towards anybody who has not been exposed to different narratives for their

attachment to the narrative. But what I do ask, which I think is the reasonable ask, which I think is very similar the ask that many people that

belong to marginalized identities have, is to educate themselves, because I think, you know, at the end of the day, history is there for anyone to open

a book and engage with it.

MARTIN: One of your specialties is trauma, and of course, you know, American Jews or Jews all over the world still carry the trauma of the

holocaust, as well.

ALYAN: Sure.

MARTIN: And how do you think about that?

ALYAN: Yes. I mean —

MARTIN: I mean, is there a way in which their discussions around the holocaust have, in a way, made some space for other people to talk about

their experiences of intergenerational trauma? What do you think?

ALYAN: When I talk about sort of standing for and fighting against persecution, that applies to everybody, so that absolutely applies to folks

who have been — are sort of the descendants of holocaust survivors, that involves standing up against anti-Semitism, that involves standing up for

black lives. So, I believe that any community that’s been persecuted as many Jewish communities have been are absolutely part of this conversation

of intergenerational trauma.

MARTIN: But I’m just curious, like how do you think about the fact that so fundamental to the way American Jews think about Israel is so connected to

how they think about holocaust as a refuge for — from the holocaust and as a way to offer safety and sanctuary for people who have been so viciously

persecuted not just in that era but throughout centuries? I realize it’s a difficult and a heavy topic, but how do you integrate those parallel

realities?

ALYAN: So, I start separating (INAUDIBLE) Judaism, which I think is really important and which I think a lot of like Jewish community leaders and

Jewish organization, including Jewish voices towards the (INAUDIBLE) have been very precise about. I think it’s really important to make it clear

that holding a state or a government accountable for their human rights violations has nothing to do with anti-Semitism. It has nothing to do with

speaking against Jewish communities. And I think the Jewish voices that have actually been really beautiful and essential in the Free Palestine

Movement are all the evidence I need for that, right?

So, for me, they — I think that it’s really important to think of the Free Palestine Movement as part of a broader collective struggle against

oppression, against persecution. So, I do not — that includes anti- Semitism.

[13:45:00]

So, for me, I do not think that these things are contradictory. I don’t think that — I don’t think of it as you stand against anti-Semitism but

you also are for free Palestine. I think of it as, you stand against anti- Semitism because you are for free Palestine. So, for me, they are not in any way contradictory. They absolutely are hand in hand.

MARTIN: But what I’m asking you is how you think about people reconcile their realities which are both true, which is that people have a historical

experience of oppression which leads them to a certain place and a certain understanding of the world and a certain desire which conflicts with the

desires and historical experience of other people. That’s what I’m asking you.

ALYAN: I mean, I don’t know that it conflicts with it. I think at the end of the day, and this was captured eloquently in the report that was

published in April of this year by Human Rights Watch. At the end of the day, what we’re talking about are apartheid policies by the Israeli

governments that speaks to the survival of the democracy as a Jewish democracy being predicated on the erasure of Palestinians. So, that really

feels very different than talking about having a place that’s a safe refuge for everybody.

What I think people are advocating for is quite simple, a place where everyone lives alongside each other with equal rights. And to be perfectly

frank, the barrier to that will always be occupation, it will always apartheid policy and it will always be ongoing violence possession. That is

the barrier to everybody living with equal rights alongside each other.

MARTIN: You kind of grew up with parallel discussions, if I can put it this way. There were discussions that I think people who have — who were

Palestinians have had — have been having for generations that have not always been as much — a part of the mainstream political public general

discussion as they are now. The question of the database circumstances of Palestinians. Do you feel like, you know, where you kind of sort of fight

for that story to be told?

ALYAN: Yes. I definitely think so. I mean, I think —

MARTIN: And what do you think has made the difference now?

ALYAN: You know, I go back to this idea that I think the intersectionality, discourse around intersectionality of social justice

movements has been crucial. I think that when you see BLM issuing the statement of support for Flee Palestine, when you see people on the street

that are marching for these protests belong to various indigenous folks from this land, belonged to our Jewish brethren, our Jewish kin, when you

see people rising up together, I think that we are at a moment when we’re realizing — we’re having a reckoning, I think, in this country, as in a

lot of places, where we’re starting to realize that you do not get to pick and choose whose human rights you fight for.

You do not get to choose whose human rights are more worthy over the others. That if we rise, we rise together. And that the offer to stand with

persecuted and oppressed people to not be conditional.

AMANPOUR: Doctor Hala Alyan, thank you so much for talking to us.

ALYAN: It was my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

Marc Lipsitch; Ed Yong; Hala Alyan; Kev Marcus and Will Baptiste

LEARN MORE