Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.”

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

EBRAHIM RAISI, IRANIAN PRESIDENT-ELECT (through translator): Regional issues or ballistic issues are nonnegotiable.

AMANPOUR: Iran’s new hard-line president. What does the election of Ebrahim Raisi mean for the future of the country and reviving the nuclear

deal?

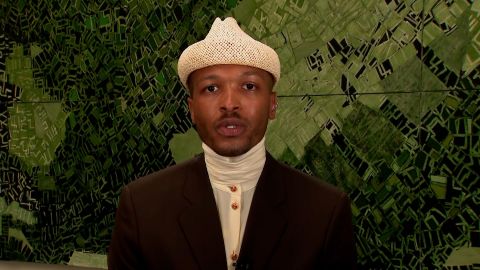

Then: giving space to black artists. The young curator with a mandate to shake up the art world, Antwaun Sargent, joins me.

Plus:

HAKEEM OLUSEYI, ASTROPHYSICIST: As we say in Mississippi, I found myself looking down on the stupid end up too many gun barrels.

AMANPOUR: World renowned astrophysicist Hakeem Oluseyi on his unlikely journey from the street to the stars.

And, finally, Little Amal’s journey, the giant puppet refugee trekking from Turkey to Manchester in support of what connects us. Director David Lan on

the simplicity, strength and symbolism of this project.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Iran sends out geopolitical ripples as it elects its most hard-line leader since the Islamic Revolution 43 years ago. Ebrahim Raisi, an ultra-

conservative cleric handpicked by the supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, will take office in August.

In his first press conference, he called on the United States to get back into the 2015 nuclear agreement that former President Donald Trump withdrew

from.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

RAISI (through translator): I’m seriously proposing to the U.S. ministration that, immediately, they should stick to their commitments and

abide their commitments. They should remove all the sanctions. And they should prove that, by lifting all the sanctions, they’re honest.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Now, inside Iran, the election saw historically low turnout, a sign of disillusionment.

Many see Raisi as the future face of the regime poised to replace Khamenei. And the supreme leader’s protege takes power at a critical time for the

country. The economy remains crippled by U.S. sanctions and unemployment is high.

David Sanger is chief Washington correspondent for “The New York Times,” and he specializes in covering nuclear proliferation. And Ellie Geranmayeh

is a senior policy fellow focusing on Iran at the European Council on Foreign Relations. And both are joining me now.

Welcome back to the program to both of you to discuss this latest happening inside Iran.

So, David, I want to ask you, because, really, I guess the U.S., the world wants to know, will this nuclear situation be resolved by Iran coming back

to a deal with the United States? At first blush, how do you think? What’s the outlook for that?

DAVID SANGER, CNN POLITICAL AND NATIONAL SECURITY ANALYST: Well, I don’t think it’s going to be resolved, Christiane, but I do think that there’s a

high likelihood that you will get back to the deal, or something approximating the deal, that we saw in 2015.

That seems a little bit odd, considering that Mr. Raisi is considered a hard-liner and was part of the group that really opposed the original deal.

But he’s really the only one who can get the Iranians back into it.

It’s sort of a Nixon goes to China scenario here. Because he endorsed the return of the deal during the campaign, on the theory that it would relieve

the sanctions, he’s now in a position to basically override all of those who objected to the terms of it at the time.

Now, there’s a lot to be done between here and there. While the return itself, the wording of it is been all set, at least on paper, for weeks,

the fact of the matter is that the Iranians want a commitment from the United States that it will never again pull out of the deal the way Trump

did.

And the Biden administration simply can’t give them that assurance. And the Americans, for their part, want an assurance from the Iranians that they

will then negotiate a longer and stronger deal, to U.S. Secretary of State Blinken’s phrase, something that includes missiles, something that includes

keeping Iran from supporting terrorism.

And the Iranians and President — or president-elect Raisi has made it clear they won’t do that. So that would leave the United States back with a

deal that many found insufficient.

AMANPOUR: OK, so let’s expand on that, because they definitely want a deal. They need to get an arms control deal back in place, the one that

President Trump basically tore up.

So, Ellie, I’m going to play this sound bite to what David was saying, that the new president-elect says no to the extra, the deal-plus, that the U.S.

wants. Let’s just play this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

RAISI (through translator): Americans broke their promise. And the Europeans also did not make good on their commitments. So we are stressing

to the U.S. administration, when it comes to its commitment within this deal, Trump U.S. needs to adhere to that and act accordingly.

Regional issues or ballistic issues are nonnegotiable.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Of course, that last phrase is what the U.S. wants to see, and, frankly, the rest of the partners to this deal.

So, if both sides are sticking to their we don’t want status quo ante from the U.S., we’re not going to discuss missiles and terrorism or regional

issues from Iran, I mean, what is there, do you think, that will lead them to the nuclear deal?

I mean, can they? Can they do that as an interim thing, and then try to expand afterwards?

ELLIE GERANMAYEH, EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS: Well, Christiane, it was interesting that in today’s news press conference, Raisi, the

president-elect, sounded very similar to the current President Rouhani in terms of the bottom line from Iran.

And I think that points to the fact that decisions on these strategic national security issues are being made by, let’s say, a committee of

Iran’s political establishment, and at the top is the supreme leader of Iran.

And on this issue of missiles, Iran has been very, very adamant that it’s not going to negotiate on this issue, as things stand. On the nuclear

issue, which you asked, my own opinion is that actually the Iranian side will agree to a deal and come back to the 2015 agreement by August time,

and actually find a way to implement that, at least by that point, which will be implemented by the next Iranian administration.

And, in a way, that will leave the Raisi government in a very solid, let’s say, foundation, in that they can blame the previous government of

President Rouhani for any obstacles that they may face in the implementation. And any of the windfall that may come from U.S. sanctions

lifting will essentially benefit their economy policies and the promises that they have made during campaigning to improve the economy of the

Iranian people.

AMANPOUR: So that’s really interesting, because that’s, clearly, David, what the Iranian body politic says: We need to get the sanctions lifted,

we need to get the economy jump-started.

And even the 2015 deal didn’t give them the access to international financing that they had been promised under the deal. So, David, if you’re

in the United States — we will leave Israel aside for a moment, because we will discuss that — or in Europe, and you have seen four years of a Trump

administration and its allies try a maximum pressure campaign against Iran to try to weaken or destabilize or regime-change the Islamic regime, it

didn’t work.

Some are even saying that Raisi’s election is a direct result of that maximum pressure campaign, which completely cut the legs from under any so-

called relative moderates in Iran. If you’re a U.S. secretary of state or president or national security adviser, what’s the very best you can hope

for now?

SANGER: Well, I think when Secretary of State Blinken talks about this, or the national security adviser, Jake Sullivan does, what you hear from them

is the following.

First, maximum pressure failed. It did not collapse the regime, and it did not force them back into the strictures of the 2015 agreement or force them

to go renegotiate it. That’s what President Trump and the former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said would happen, and it didn’t happen.

So the next question is, is their step-by-step strategy to get the Iranians back in going to work? And I think it’s pretty clear, from what President

Raisi says, that we will get back to where we were in 2015.

Now, the critics of doing that here in the United States say that the problem with it is, the United States will lose all leverage over Iran. It

won’t be possible then to get the longer and stronger, to get the missile deal, because you would have relieved the sanctions.

The answer the administration gives to that is just what you said before, Christiane, that the Iranians have things they want. They want to be able

to go operate in the international financial system in ways that they were not able to even under the 2015 agreement.

And so the administration is betting that gives them the leverage. I’m not so certain. I — my guess is that if the Iranians discovered they can sell

oil again at the prices that are now on the market, that that will be enough for Raisi to claim a significant victory.

And if they can get the deal in the next few weeks before he takes office, if anything goes wrong, they can blame the previous government.

AMANPOUR: So, Ellie, you look a lot at the — inside Iranian politics. And we already heard Raisi at his inaugural press conference talking about

wanting to improve relations with the Gulf states, those very same Gulf states who have just signed the Abraham Accords with Israel.

He talked about wanting to reopen embassies between Saudi Arabia and Iran, again, Saudi Arabia, who wants nothing more than to make this deal go away

and to — they would very much like to topple the Iranian regime.

What foreign policy do we expect to come out of the Raisi government? And the question of leverage, I mean, look, for 40 years, the United States has

tried everything, sanctions. There’s — and all the rest of it that we have seen, and it hasn’t worked, frankly.

So, address leverage, in conjunction with Iran seeming to reach out to the very ones the Trump administration were trying to bring in the fold, the

Gulf states.

GERANMAYEH: Sure, Christiane.

And so, on the question of foreign policy, it’s interesting, because some voices, even within the reformist faction in Iran who boycotted these

elections, basically were of the view that if all of the branches of power were in the hands of one group, consolidated in the hands of the ultra-

conservatives, then they would streamline decision-making both on domestic and foreign policy issues, so that there would be less infighting.

And there is a very slim possibility that that could actually result in more deals being made, not just with the Gulf countries, but perhaps on

regional issues with the United States, for example, on issues like Afghanistan and Iraq, which are neighbors of Iran, and very important

issues for the United States as well.

I’m less optimistic that that’s possible, because we heard very similar things even under the previous Ahmadinejad government. And, really, the

tone that came out of foreign policy under that previous government really created stumbling blocks. And perhaps the same will be seen under the

Raisi.

But I do think there is a common position in the Iranian political establishment that they need to have some sort of rapprochement,

particularly with Saudi Arabia, in a way that undoes some of the strength in the relationship between the Arab Gulf countries and Israel in

particular that is, obviously, to the detriment of Iran’s foreign policy in the region.

Now, on the question of leverage, which I, frankly, think maximum pressure was always a fallacy in terms of leverage, given that it exhausted itself,

both politically and economically, in terms of giving results, my view is actually that the Biden administration’s biggest leverage card will be to

prove to Iran that sanctions-lifting is possible, after a very, very turbulent experience under Obama and then Trump.

And then that in itself will create a very effective tool, I believe, for the Biden administration to snap back future sanctions if they really hit a

stumbling block and a dead end with the Iranians on further talks that the U.S. administration is seeking.

AMANPOUR: OK.

GERANMAYEH: So, actually, the biggest way, in my view, to exert that leverage is by proving that sanctions can be effectively lifted.

AMANPOUR: OK, so you mentioned Israel. You mentioned Ahmadinejad.

David, you have covered this angle exhaustively. Obviously, throughout the entire many years of the Netanyahu government, his raison d’etre was to

kill this deal and to not let anything like that happen.

Ahmadinejad, the last histrionic hard-line president, anti-Semitic, Holocaust denier, hugely belligerent, the Israeli intelligence at one point

said he was our perfect poster child to unite the world against Iran.

And this now is what the new Israeli prime minister, Naftali Bennett, is saying about Raisi.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

NAFTALI BENNETT, ISRAELI PRIME MINISTER: This weekend, Iran chose a new president, Ebrahim Raisi. Of all the people that Khamenei could have

chosen, he chose the hangman of Tehran, the man infamous among the Iranians and across the world for leading the death committees which executed

thousands of innocent Iranian citizens throughout the years.

Raisi’s selection is, I would say, the last chance for the world powers to wake up before returning to the nuclear agreement and to understand who

they’re doing business with. These guys are murderers, mass murderers.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: He’s made his point there.

What do you think, David? Are we going to be in for yet another Israeli government that stands against the United States, that does everything it

can to corral public and other national opinion and efforts not to let this deal happen? In other words, is a Bennett government going to follow

Netanyahu’s position on this?

SANGER: My guess is that they will follow something close to the position, but probably not do what Netanyahu did, which was go to Congress, try to go

over the head of the president, as they — Netanyahu did when he came and addressed Congress and opposed to deal that Obama was putting together.

I don’t think that Prime Minister Bennett has got that kind of clout right now. And he’s obviously got a very fragile coalition.

I think the really interesting question, to my mind, Christiane, is, do the Israelis continue to do the offensive campaign that they have been running

against the Iranian program while the U.S. is getting back into the deal?

I mean, think about it. Last summer, the R&D facility at Natanz blew up. In the fall, the — one scientist who had won most of the nuclear program was

assassinated on the way to his weekend house by the Israelis. The Israelis made no effort to hide their involvement in that.

A few months ago, we saw another explosion down in the main centrifuge hall. So, the Israelis have pursued a policy of mowing the lawn here, as

they call it, blowing up elements of the program, just as the Americans are trying to come together on a diplomatic solution.

And that is a prescription over time, I think, for a significant rift between the United States and the new government of Israel, if it

continues. We have a new prime minister. We have a new head of the Mossad.

AMANPOUR: Interesting.

SANGER: Yes.

So, we just don’t know which way they will go.

AMANPOUR: Yes. No, it’s fascinating to watch that. Yes, you’re absolutely right.

And, finally, to you, Ellie, because you heard what Naftali Bennett said. All the human rights groups have been saying the same, calling out Ebrahim

Raisi for being on those death committees, for sending and agreeing to — signing the death warrants and executions of hundreds, if not thousands of

political prisoners, his hard-line decisions during his chief judiciary period, plus a historically low turnout, kind of delegitimizing the

election.

Tell me what you foresee for somebody who has those calling cards and credentials, particularly for inside Iran, for the people, for the — how

you think they will react?

GERANMAYEH: Christiane, I’m very concerned that there is quite a bleak several years ahead, in terms of domestic politics, that there’s going to

be — the space is going to be increasingly squeezed for any dissent, particularly for political dissent, in the country.

There might be some space still for those who are critical of economic policies, for example, but the faction, the reformist faction, for example,

that’s led by the former President Khatami has already been really dislodged from power. He called for people to come and vote in these

elections for the most moderate-sounding candidates.

And people just boycotted. And so this, to me, also indicates a real divide emerging between all of the political leaders in the country and the

society as a whole. So, I think there’s going to be a process of reflection over the next four years for the reformist, the more moderate factions in

the country, if they are allowed to have the space to do that. We will have to see.

And I think that, by this extensive boycott, that the lowest ever turnout for presidential elections in the Islamic Republic of Iran’s history is

really a warning sign that from the people that their expectations are really not being met by the political establishment.

My fear also is, the way that the very hard-line vetting body for the presidency, the Guardian Council, in this presidential race squeezed out

any critical voices, any reformist voices or moderate voices from standing indicates that we may be shifting away from the republican elements of this

system and towards something very different, which could be similar, for example, to a Chinese committee model of political leadership.

Or, as some authorities in Iran have pointed to, perhaps they might want to shift towards the Gulf monarchy systems, which will really undo some of the

slogans of the Islamic Republic revolution.

So, I do think the next eight years will be very critical. Of course, there’s also the issue of the supreme leader and a smooth succession.

AMANPOUR: Right.

GERANMAYEH: And that’s going to be a real political game-changer, in my view.

AMANPOUR: It really does seem to be consolidating around a hard-line maybe military position in the future.

Ellie Geranmayeh and David Sanger, thank you both so much for joining us.

And now for our cultural moment colliding, as it always, at least often, does with the politics of our time.

At just 32 years old, art writer and curator Antwaun Sargent was recently named a director at Gagosian, the global gallery known for ambitious

exhibitions. And he plans to curate exhibitions devoted to black artists.

His first show does just that. Social Works looks at what he calls notions of black space, works of art that he says are doing more than just sitting

quietly on a wall.

And Antwaun Sargent is joining me now from New York.

Welcome to the program. It’s great to have you.

And I just want to start by asking you, tell me what you mean about space. Or how do you define space? And what do you mean by art that is not just

sitting somewhere on a wall?

ANTWAUN SARGENT, CURATOR AND DIRECTOR, GAGOSIAN: Hi, Christiane. Nice to see you. Thanks for having me.

What I mean is that the exhibition Social Works really sort of thinks about the ways in which artworks are socially engaged in communities and how

they’re sort of thinking about sort of space politically, socially, institutionally, and even psychically.

AMANPOUR: So, tell me a little bit about — I sort of said this collides with our political moment.

And you’re putting all this together at a time of maximum consciousness, really, the Black Lives Matter movement, the steps that have been taken, to

an extent, since last year. Tell me how you see the moment playing into the art.

SARGENT: Yes, I mean, I feel like the last year of pandemic and protest has really sort of made us reconsider the ways in which we are engaging

with space.

And I think there has been a group of black artists working in their communities, from Lauren Halsey, who is working in Los Angeles, who sort of

provide food to folks who have lost jobs during the pandemic and protest, to folks like Theaster Gates, who is working in Chicago on the South Side

of that city, really sort of energizing that city with his Rebuild project, where artists and community — and folks in the community are invited in to

participate in sort of making art, but also rethinking the ways in which they can revitalize their community.

AMANPOUR: So, you have got a series of artists, and we can’t profile all of them.

But one of the — certainly the one that resonated with me and whose work I know because of the museum in Washington, David Adjaye, the architect. He’s

one of your featured artists. Tell me about why. What does this architect bring to this particular brand, which is Social Works?

SARGENT: Yes, I think that David has been an architect and has built some wonderful buildings in London, in New York and around the world.

And in the gallery here in New York, he’s going to be presenting his first large-scale sculpture made literally from the earth that we walk on here in

New York. And so the sculpture, which weighs well over a ton, is made from limestone, right, which is the bedrock of New York City and New York state.

And David is really sort of considering sort of our relationships — through the materiality, David is considering our relationships to the

earth, to the ways in which we engage with the earth, the ways in which folks occupy space, right?

And so as you sort of go through the sculpture, those are some of the ideas that David would like you to consider in relationship to this new work.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you, because he’s also pretty well-known for his spaces being devoted to black history. As I said, he designed the National

Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. It’s part of the Smithsonian, I think.

In any event, he’s really put his marker down. Was that important for you?

SARGENT: Yes, I mean, I think what was important is, you have a group of 12 artists.

So, it was really sort of thinking about the different ways that black artists are engaging spaces, right? And so you have David, who’s obviously

thinking spatially in terms of architecture, but then you have also other artists like Carrie Mae Weems, who’s thinking about sort of her

relationship to space through a series of photographs, where she sort of juxtaposes herself to monuments and to public squares.

And so we can consider the ways in which the black body is represented and treated and mistreated in those spaces, right? And so, throughout the show,

you really have a dynamic mix of artists really sort of thinking about how black people, blackness is sort of considered in our public and private

spaces.

Another artist in the exhibition is Rick Lowe. And his painting, which is behind me, really sort of thinks about Black Wall Street, right, the 1921

Tulsa, Oklahoma, race massacre, right? We’re on the centennial of that, right? And so through his abstract use of colors, red and green and blue

and black and white, he’s really sort of thinking about the history, trying to conjure not only the violence, but also the profound economic loss, and

also the ways in which folks in that community of Greenwood have sought to rebuild and have sought to sort of make the country remember that massacre,

remember that moment in our history.

AMANPOUR: And the president has just said that it will be a national day of memorial. And that means times are changing.

And I just want to ask you, because, reading for this interview, come across the name Linda Goode Bryant, who was an artist, a filmmaker, et

cetera. And, in the ’70s, she had tried maybe a different version of what you’re trying to do, to lease space in Manhattan to showcase the work of

black artists.

And she famously says she got one of two responses from agents and landlords, a hung-up phone or a string of racist remarks, followed by a

hung-up phone.

Well, it’s taken nearly 50 years for you to make your spaces. Are times changing, or is it still going too slowly? Compare you and Linda.

SARGENT: Yes, I mean, I feel like the reason why I’m here in the gallery doing the work that I’m doing is because of folks like Linda Goode Bryant,

right, who, as you said, started a gallery in 19 — in the 1970s, just above Midtown, in Midtown Manhattan, on 57th Street.

And it was difficult, right? And I think that fast-forward 50 years later, to have me sort of curating Linda — in this exhibition, she’s making a

living sculpture, where that — where farming is actually happening in the sculpture.

And so Linda’s team from Project EATS, which is an organization in New York City that has 13 urban farms that delivers food to under-resourced

communities, will be harvesting her sculpture, and giving away the vegetables and herbs that they grow in the gallery.

But Linda always talks about how, for her, her artworks are spaces with real-world consequences. And I think that I stand in a way on the shoulders

of folks like Linda, who did the hard work in the 1970s and even before that to really sort of take space, and show what the possibility of taking

that space can be for black art and black artists.

And so Linda, for me ,was a huge inspiration started in my career. When I got the opportunity to sort of put her in an exhibition that sort of deals

with these questions of space, deals with the question of occupying space, I was just more than thrilled.

And so I think, on that score, you can say that there has been some progress. But I think that there needs to be more. There needs to be black-

owned galleries. There needs to be black artists showing in institutions more. And I think we’re just getting started.

And I think that there’s a lot of progress for us to make going forward.

AMANPOUR: And, finally, a personal question.

I said you’re 32. You’re young. Much has been made of your youth, and also of the sort of institution that Gagosian is. And I just wanted to know,

what do you see as the challenges and the opportunities for you, having this director position at this space right now?

SARGENT: I think that I’m incredibly excited to be at the gallery.

The gallery in a lot of ways is space. And I think what is exciting about this space of the gallery is that there’s a lot of different things that

can happen in this gallery.

And so to put on a large-scale sculpture by David Adjaye and to present Linda Goode Bryant’s works and Theaster Gates and others is really sort of,

I think, one way that we can use this space, but I think there are other ways that we can use gallery spaces as well to make sure that all folks

that are a part of our communities in places like New York feel welcomed in these galleries and institutions, which has not always been the case.

And so, for me I just really sort of take, you know, that challenge really as an opportunity to widen the scope of what art can do, the possibility of

bringing folks into our gallery and bringing folks into other institutions to make sure that, you know, they have an opportunity to connect with the

artist and the art works.

AMANPOUR: Right. Antwaun Sargent, good luck. Thank you for joining us.

Now, a story of achieving greatness in the face of adversity. Hakeem Oluseyi grew up in some of the roughest American neighborhoods. His father

was a drug dealer and his mother dropped out of high school at 16 after she became pregnant. His life seemed destined to follow in their footsteps, but

he’s now a world-renowned astrophysicist. His new memoir is called “A Quantum Life: My Unlikely Journey from the Street to the Stars.” And tells

Hari Sreenivasan how he beat the odds.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN: Christiane, Thanks. Hakeem Oluseyi, thanks for joining us.

First, the name of the book, “A Quantum Life.” Now, I’m not a scientist but when I hear the world quantum, what I do know is that things can exist in

multiple states at the same time. What are the different states that your life exists in or existed in?

HAKEEM OLUSEYI, AUTHOR, “A QUANTUM LIFE”: Well first thank you so much for having me. You know, I call it basically the gangster side and the nerd

side. And so, I was schooled by my family in crime. And then I was a full participant. And at the same time, I was really interested in the natural

world and I wanted to be a scientist. And so, those two things were in conflict with each other.

SREENIVASAN: You talk about moving around a lot as a child in your early life. So, as you are moving around between Louisiana and Mississippi and

Los Angeles there were people, members of your family that were part of gangs in L.A. What did you see? What did you learn from that?

OLUSEYI: You know, it is more than just a gang. I got it from every part of the — you know, I got it from my family, I got it from my community, I

got it from the gangs. And my cousins, you know, they basically schooled, you know, me on how to survive. We’re about to go out. Here is how you need

to behave in these circumstances. If you hear this, do this. Right? They trained me.

But, you know, one thing I learned is how to ignore my pain, whether it was the pain of hunger or the pain of, you know, fighting. And so, when I

became an adult, you know, and after that, I went into the country where the, you know, work ethic is really hard core. By the time I’m an adult,

you know, I felt like, yes, maybe I am undereducated in comparison to my peers but I can outwork anybody. And so, that’s what I set about doing. And

a part of working hard is ignoring the pain. So, when others would stop, I’m going press on. I’m going to keep going.

So, this book is basically showing what I went through. Showing you what the communities are like. Showing you what people go through that are

different from the lives of most people. And even the way I got into being an astrophysicist, it was not, what do I want to be when I grow up, and

approach it. It was every day, how I do live indoors today, how do I eat today? That was my struggle. I did not get to a state of not just surviving

until I was deep into graduate school.

SREENIVASAN: I also want to ask a little about what you got from your dad, because he was for a large part of your life absent and in many ways, he

taught you a life that would have led you down a much worse path if you did nothing but follow it? But at the same time, throughout this arc of the

book, you are coming to terms with a son and a father.

OLUSEYI: Yes. Yes. Yes. That is the reality of it. My father was a complex human being. And, you know, so much of our actions are determined by

survival. My father was born in 1933 in rural Mississippi. He dropped out of school when he was nine years old. He left home at 13, went to the city,

New Orleans. And according to him he got a job parking cars for 25 cents a day. And then when he turned 18, he went away, the joined the army, went

away to the Korean War.

Now, our family, my father’s family, Mississippi always been entrepreneurial and, you know, he had to be self-sufficient because there

weren’t jobs to be had. So, they were bootleggers. And my dad took it to the next level. He started a growing operation in Mississippi and an import

operation in New Orleans and he was a wholesaler.

SREENIVASAN: Of marijuana?

OLUSEYI: Exactly. Marijuana. And I started with my dad’s business at the age of nine — excuse me, eight years old, when I was reunited with my

father, after being gone four years.

SREENIVASAN: What were you doing in your dad’s drug business as an eight- year-old?

OLUSEYI: Well, so you — first of all, when the product comes in, it has to be cleaned and packaged. The second thing is, when we were in

Mississippi, sometimes everyone would leave the house and I’d be left alone at the house and I’d be the person who conducted the sales.

SREENIVASAN: You wrote that early on you had an I.Q. test when you were a young boy and it was off the charts. It was 160, 162.

OLUSEYI: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: There’s an aha moment that you describe when you are sitting in a stairwell reading basically an encyclopedic description of Einstein.

Tell me a little bit about that.

OLUSEYI: Yes. So, the year before at age nine, I read my first novel. It was the book “Roots” by Alex Haley. And I was amazed. I had already fallen

in love with reading, but I would read kids’ stuff, comics, books with pictures, things with humor in it. But now, I just read a book that was

serious. And what I found was that it was like a movie was playing in my mind. So, I’m like, I want to read as many adult books as possible.

And I looked around our home, I was left alone a lot, and there was sitting the set of encyclopedias. So, I thought, well, I’ll just read those A to Z.

And I got as far as letter E and that’s when encountered Albert Einstein and relativity. So, I’d always been attracted to the natural world, right?

First, it was Jacques Cousteau. So, when I was like five, six, if you asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I’d say an oceanographer, right? It

was also, Wild America.

But when I encountered Einstein, relativity had that weirdness that I love. I loved things that were really weird. And so, when you combine my love of

nature with love of the weird, you land right square in physics.

SREENIVASAN: Statistically speaking, you should not be having this conversation with me today. Given how deep you went into sort of the

criminal life and what the odds were of all of the things lining up for good and for bad to get you where you are.

OLUSEYI: Yes. Yes. That’s absolutely true. And I am very lucky in this sense that I got a lot of help. That was timely. There’s professors from a

nearby university who are like, oh, you guys should participate in science fairs. At our school, we had never heard of science fairs. And because I

had been studying relativity and recently thought myself the program in the program language basic, I thought, oh, I’ll program all the effects of

special relativity, and ended up winning first place in the state’s science fair.

Then my navy recruiter shows up. And he was like, yow, man, I’m going to find a way to get you into college. And he gets me into this program in the

navy where they take people from Rural America and inner cities and they give you a year of hardcore academic training and send you to college to

become an officer. And it was there that my mathematics was shored up. So, that when I got to college I could actually pass.

I didn’t think of going to college. When I got out in the navy, my friends were like, dude, what are you doing? Come to college. And I went. And when

I got to college, I had no idea what to do because, you know, there was no one in my family who had even graduated high school. So, you know, lot of

people helped me out along my path to the point where it almost seems like it was destiny. But I had to fight and work super hard every step of the

way.

SREENIVASAN: And you end up going to a historically black college.

OLUSEYI: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: A small one that probably nobody at your graduate program had ever heard of.

OLUSEYI: When I got out of the navy, I was aimless. It was 1986 and I was looking for a job. And some of my friends told me, man, you need to come to

college. And I was like, I don’t know. And they were like, come up Tougaloo where we are. You will love it. I showed up at campus without even

applying. So, I didn’t know how the process worked. But they knew how to deal with students like me and they got me enrolled.

And so, you know, I was kind of aimless when I first started. Things went downhill for me very quickly. And I dropped out. And I got this job as a

janitor. And the reason why I did that is simply because I wanted to live. As we say in Mississippi, I found myself looking down the stupid end of too

many gun barrels.

And so, I got this job as a janitor. And I thought that, you know, I could work my way up in the hotel, someday be a hotel manager. And what happened

is, when the bellhop got fired, I thought this was my big break because, you know, as a bellhop, I could maybe get a hundred dollars in a day,

right? Man, I was not bellhop material. I wasn’t front door material. And I thought to myself, I can’t go from janitor to bellhop? I’m going back to

college.

SREENIVASAN: So, you get through your undergraduate work, and then you qualify to be among the elite in the country as a grad student at Stanford.

What happens there?

OLUSEYI: When I get to Stanford, it is completely new environment. I’m introduced to classism for the first time. You know, I grew up in the deep

south and the issue was always racism. And I remember chatting with my mother on the phone and she made some mention of race. And I said to her,

mom, being white ain’t even good enough here, because, you know, it was really about class. You know, I didn’t see anybody around me with a deep

southern accent, for example, like I had back home.

And when — you know, I — when we got there, us physics students were given a list of everyone else who was a first-year physics graduate

student. And it read like a list of the top universities in the world. All the top U.S. universities in. And then Tougaloo College. And so, the

students, at first, they were like, oh, this guy must be a genius. But, you know, I was still vastly undereducated in comparison to my peers.

So, there is a mixture. There’s people — most people are just concerned with themselves and then you meet some people that are really good people

and you meet some people that are hostile to you. And that’s what I happened to meet. And the hostile people happened to be in the physics

department. And some of them were my professors.

The beginning of my first four years, starting my second year, third year, fourth year, it was like a ritual that they would attempt to undermine my

progress. The next year, they suggested to me that I should leave the program. And you know — explicitly. And I don’t and go on to have a very

successful research career.

SREENIVASAN: You were at Stanford, in grad school, literally doing rocket science. And by night, at one point, you are out trying to score crack.

OLUSEYI: Yes. You know, I never — once I came into this world and I left my past behind me, I never mentioned it again. And so, this is the first

time in this book that I’m revealing this to the world. I hate hearing that word associated with me, but, you know, it’s the reality. I had three bouts

with that in 1988, 1990 and 1992.

In 1992, I was 25 years old. And that is exactly what happened. I got to Stanford University, and I didn’t realize how much I was in trouble with

addiction. If you haven’t been through it, it is hard to imagine. It is so insidious. It’s such — you know, people say it calls to you and it comes

to you in your dreams. It is all true. It really is. And so, I found myself in trouble. And I found myself in East Palo Alto. And the funny thing is,

if you have ever seen the movie, “Dangerous Minds,” I was actually tutoring mathematics at that school at the time.

So, while I was — whereas I’m, you know, trying to uplift people from my background, I’m destroying myself. But, you know, that was a part of my

growth. Because going through what I went through as a youth, I did find — I did feel worthless, you know, and I did feel like I wanted to destroy

myself. But, you know, I use the example of the person who feels like they want to commit suicide and jump off a bridge. But once they get in the

water, they start to swim because they really don’t want to die. And that is where I was.

You know, I was on a self-destructive bent, you know, because of all I — the abuse I had suffered, all I had internalized. But really, I wanted to

live. I didn’t want to die. But, you know, what I had learned was when these tough times hit, you know, maybe it is me. Maybe I need to destroy

myself. And so, I hit rock bottom and I’m like, you know, I have to change this somehow.

SREENIVASAN: You were not only using, but you were also dealing these drugs when you were at Tougaloo.

OLUSEYI: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: And I wonder if this is the first time you’re revealing some of these things in the book what your peers or colleagues or others have

been thinking about.

OLUSEYI: Yes. I wonder what they’re going to think also. But you know what, I realize that it’s not about me at this point. The reason why I

wrote the book, as I — I started going out speaking and inspiring others to careers in STEM when I was still a graduate student. And people get it

when I am the person who is delivering it to them, right? They realize it is cool. They realize they can understand it. They realize they can do it.

And so, people — you know, I’ve created a generation of scholars from different communities. So, I realized that my story has such a power to

uplift people, that, you know, my — I’m more — I’d be ashamed at myself if I didn’t tell it. You know, and that’s the toughest scrutiny I have to

live with, is dealing with what I think of myself, and I see it as responsibility.

SREENIVASAN: You find a mentor here. What did that mean to you? And what did he do for you?

OLUSEYI: Yes. Art Walker was one of the first three African Americans to go into astrophysics in America. He got his PhD in the 1960s. And he was

one of two black faculty in all of the six schools of science and mathematics at Stanford University.

And so, when I got to Stanford, I wasn’t going in there with the mindset, oh, I’m going to go and work with the black professor. I was looking for

experimental astrophysics. And it turned out that the only person that did experimental astrophysics was Art Walker at the school at the time.

And so, in the physics department, there was Phil Schairer (ph) in applied physics. So, I thought that I’d work with Art. And Art taught me not only

how to be a scholar, he taught me how to be a gentleman. He gave me a different example of being and he also a different example how to behave

professionally and how to handle difficulties when they arise in a professional world. And that’s been very important. Because, you know, the

workplace is fraught, and I’ve survived wrongdoing by others because of what Art taught me.

SREENIVASAN: Well, in non-science speak, what did you and Art, what did you study together? What did you discover together?

OLUSEYI: If you look at the structures on the sun, there are these plasma loops, there are these plumes. We were discovering how this atmosphere,

even though the surface of the sun is just under 6,000 degrees kelvin, how does it have this extended atmosphere over million degrees indefinitely,

what we call the solar corona? And if you think about how strong gravity is at the surface of the sun, why is this atmosphere streaming out into space

to form the solar wind? There must be some powerful force here. So, we made advances in understanding how the atmosphere is heated and how the solar

wind is accelerated.

SREENIVASAN: Do you think that Art and yourself were questioned by the scientific and academic community differently because you were black

physicists?

OLUSEYI: Well, it is not something that we have to ponder. Because, you know, people are sometimes very explicit about this. It was — you know, I

heard faculty say, oh, Art Walker, he doesn’t know anything. Which was ridiculous. If you knew Art, Art — like if I ever met a genius, and I’ve

many, but Art was on another level. And he was super square too, right? So, that even makes you more genius.

And so, I thought to myself, if he’s getting it, I don’t stand a chance. I feel like this. You know, you are born into a world. And I have to survive.

And I’m looking to thrive. So, if that’s the conditions that I’m in, that I have to fight and survive and thrive under, then that is the conditions

that I’m in. So, that is exactly what I’m doing. And I’m training others to be successful as well.

SREENIVASAN: So, tell me in kind of basic terms, what are you doing today? What are you studying? What are you exploring?

OLUSEYI: I’ve been doing recently what is known as galactic archaeology, that numbering of the stars, thing allows you to untangle the structures

that made the Milky Way Galaxy. And so, when you understand how galaxies form, you can understand in part how the universe formed.

And the other thing is, when we look at the surface of the sun and how the sun accelerates particles to form the solar wind, one of my graduate

students realized, hey, we can make a machine that does the same thing. And so, we created a new ion propulsion technology. And, of course, at all

times, I’m thinking about very fundamental problems that have to do with the origin and evolution of the universe and the nature of our universe.

SREENIVASAN: Hakeem Oluseyi, thanks so much for joining us.

OLUSEYI: Thank you for having me.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: What a powerful life journey. And finally, tonight, another journey, one of one little girl with one big hope. That is the story of

“The Walk.” It is all about Little Amal, a young refugee girl in the form of giant puppet who will travel from Turkey to the U.K. in search of her

mother.

Little Amal transcends borders and politics as part of a traveling festival with a powerful humanitarian message, don’t forget us. The walk is directed

by David Lan who has had an extraordinary walk of his own from witnessing guerilla warfare in Zimbabwe to the height of the London theater world. And

David Lan is joining us live now from London.

Welcome to the program.

This is an extraordinary project. I mean, she’s a massive 11-foot puppet. But the logistics aside, I first want to know, what inspired you? What are

you saying with this?

DAVID LAN, WRITER AND PRODUCER, “THE WALK”: Well, she’s very big. She’s a very big little girl. But she is just a little girl who is on a long

journey because she’s looking for her mother. We started from a very simple premise. A number of us had been involved in the creation of a play called

“The Jungle” which was about the creation and the demise of a refugee camp in Calais, that was there for a number of years and to some degree is still

there, occupied by people who are fleeing a whole range of disastrous circumstances in their home countries. People from Afghanistan and Syria

and Iraq and Iran and so on.

And two young writers wrote a play about the experience they’d had of spending time. They had spent about seven months in the refugee camp. One

of the characters in this play is a little girl, who in the play is called Little Amal. We produced the play — I produced the play when I was running

a theater in London. And we took the play into the west end in London. We brought it to New York, we brought to San Francisco, and the show is still

alive. And when it is possible to do theater again, we will do it again.

But in the course of making the play, creating the show, we took too many people, young people, old people, children who had made the very long

journey out of warfare, out of disaster looking for safety. And we felt having heard from them of their experience, that as artists, I mean, we’re

artists, we’re theater people. We’re not politicians or diplomats. But we felt that something more than creating that play was necessary. And we came

up with the idea of paying homage to this extraordinary experience that hundreds of thousands of people have had over the last year of crossing

these vast distances often on foot. But ourselves walking.

But in addition to ourselves, we have the idea of doing it as a play. And really what we’re doing and one of the producers of this event, which is a

play on an 8,000-kilometer-wide stage of —

AMANPOUR: OK. I mean, it is massive, David. And I just want to put up — David, I want to put up the map just to show people exactly the context you

are talking about. Because it does start, and it is a massive long walk. It starts at the Syria-Turkey border, at Gaziantep, which we’ve become to know

so familiar since the Syria War, and it comes all the way to Manchester.

Just before I get to more of the actual content, you know, many people, I guess, want to know, how do you move? How do you shift an 11-meter puppet

and all the paraphernalia that goes into this walk? What’s the actual logistics and the physicality of it?

LAN: Well, it takes six people to operate Little Amal. The key person is the person inside, who is a stilt walker, who operates her feet and her

face and her eyes and her mouth. And then there’s one puppeteer on her left arm and one on her right. And the three of them together create the sense

that she’s a real little girl, though a very big one, walking down the road.

We will walk much of the distance. But of course, not all the distance. To walk 8,000 kilometers would take four years rather than three to four

months that we’ve allocated. So, the way we think about it is that we will use whatever form of transport refugees themselves might actually have

taken if you are trying to get from one place to another place and a truck comes by and offers you a lift, you would take the lift. And then same way

Little Amal can travel on the back of a truck.

She will — so, the first I hear is that she’ll walk. But the key idea is that we’ve invited artists in many, many, many places along her route to

welcome her. We said to people, if this little girl were to arrive in your village or your town or your city, how would you welcome her? How would you

look out for her? She’s vulnerable, she needs somewhere to sleep, she needs somewhere to eat. What would you do? How would you look after her?

And there are now a hundred welcomes, acts of welcome being created for her in the 65, 70 places, localities, all the way along the route. So, it is by

— it is like a traveling festival. We will enable Little Amal to arrive at the right place at the right time and the right day. And waiting for her

will be dancers in some places, theater people, painters, artists of every kind preparing a welcome for her.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

LAN: And over the period of time that we’ve been working on this, the municipalities have come on board. Mayors, many, many other people, faith

leaders who are preparing welcomes for her.

AMANPOUR: And it is going to be important. Because the idea of refugees has fallen off the international humanitarian map and it really does need

to get back on. So, it is going to be incredibly important. But I want to ask you because you grew up, I believe, in apartheid South Africa. You did

quite a lot of research. You weren’t always a theater person. You studied anthropology.

I just want to know how that youth and what you studied then informs what you are doing now and informs your art and your theater.

LAN: Well, yes, I mean, you are right. I trained as the social anthropologist and I spend two years — so, it is a long time ago now. But

I spent two years living in a village in Central Africa in the northern part of Zimbabwe just after the independent struggle there. But I think the

thing is, that what you learn — I mean, it was a very good thing to do as a young person, what you learn is that people everywhere are the same.

People have the same needs, the same desires. The —

AMANPOUR: OK.

LAN: — and what’s different and what’s the same. And that experience has certainly informed all the work I’ve done since then.

AMANPOUR: Yes, it’s a great message. David Lan, thank you so much. And this walk starts next month. Thank you for joining us.

And that is it for now. Thank you for watching and good-bye from London.