Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And our next guest is also a musical star but a very different one. Tom Morella is best known as the guitarist of the rock band Rage Against the Machine. But you’ll find his latest work in print as he’s writing a series of essays on his music and on social justice for the “New York Times” or while preparing to release his new album next month. As he discusses in conversation with Hari Sreenivasan now.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARI SREENIVASAN: Christiane, thanks. Tom Morello, thanks for joining us. How did you pull off a collab album in the middle of a pandemic?

TOM MORELLO, GRAMMY AWARD-WINNING MUSICIAN, NEW YORK TIMES COLUMNIST: It was my only choice. How it began was, I have a studio at my home but I don’t know how to work it. Normally, there’s an engineer who is moving a knob. The only one they allow me to touch is the volume know, and that rarely. So, during the — you know, during the beginning of lockdown, I was staring at a future without making music. An inspiration struck at a very — from an unlikely source. I read an interview where Kanye West was bragging about recording the vocals for a couple of hit albums into the voice memo of his cell phone. And I thought, perhaps I can record my guitar into the voice memo of my cellphone, and I did and it sounded fantastic. So, I began sending out these voice memos of guitar rips and guitar lyrics to various engineers, producers and artists around the world and began creating this kind of rock N roll pen pal community that, while I was in complete isolation here, was able to create a lot of music globally.

SREENIVASAN: So, you basically tapped into a bunch of frustrated musicians all figuring out like, wait, this is part of who I am, and that has been pent up for these days and they’re like, play some music, I can do this.

MORELLO: Absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, this record, “The Atlas Underground Fire,” it’s just a record, “The Atlas Underground Flood” come out on December 3rd where as much life raft and antidepressant as they were sort of creative endeavors. It was a way to — you know, during the really sort of anxiety-filled time to remind myself that I am a guitarist, I’m an artist, I’m a songwriter and allowing — and also, when — at that time when every day felt like it was kind of exactly the same, to have the unknown in these collaborations. You send something out. It comes back transformed. And that really felt like a life raft during a pretty troubled time.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: When I look at “Atlas Underground Flood,” I mean, what do Ben Harper and Manchester Orchestra and Break Code have in common besides you?

MORELLO: Yes. What they have is they’ve picked up a phone when I called them that particular day. It’s just — it’s like-minded musicians of different genres coming together to create something that we both love. Now, part of the mission of this, and I use the word literally like a — as a missionary work, you know, I firmly believe the electric guitar is the greatest instrument ever invented by humankind from its nuance. Spreadsnuance to its power. But I also believe it’s an instrument that has a future and not just a past. And so, by integrating my vision of electric guitar into whether it’s a song with country artist, Chris Stapleton, or EDM artist Break Code or alternative artist, Grandson, or Palestinian DJ, Sama’ Abdulhadi, finding a — like having my curation and the voice of my guitar to be the common thread through these different genres to find a way — a forward — facing forward way for rock N roll and for the electric guitar.

SREENIVASAN: So, what is it about the guitar? I mean, you have said before that it chose you. What does that mean?

MORELLO: Yes, yes, yes. I had a myriad of interests. I started playing the guitar late. I didn’t start playing until I was 17 years old. So, it was really two years in. I was a freshman at Harvard University when I was, you know, toiling away, playing some cover song in a basement rehearsal room between the foosball table and washing machine when the skies parted. I stumbled upon sort of a moment sort of improvisational bliss. And it was literally felt like a calling. The skies parted and I knew then that I would be a guitarist. I had to find a way to sort of them my political science major, you know, to pass my courses while at the same time practicing four to eight hours a day, but that was my burden to bear.

SREENIVASAN: You know, there are times when you listen to some of your early work and it is powerful, it’s rocking. I mean, it’s just super energy filled. And then, there’s times where I listen to some tracks and you’re like, this guy is at some sort of a coffee house doing an open mic night. And you wrote in one of your columns, one of the things that kind of was a distinguishing, I just want to pull up this quote. These songs enabled me perhaps for the first time to peek into my own soul when I found that it might be haunted. On the surface, I was affable, reliable, cheery rocker. When I picked up acoustic guitar, I tapped into a deep vein of the union (ph) shadow, the dark repressed aspects of my personality, they’ve cut much closer to Edgar Allen Poe than Edward Van Halen. So, are you trying to juggle these different parts of you?

MORELLO: Yes. Well, I’ve — I mean, I’ve been drawn to heavy music. For me, first, it was heavy metal then it was punk rock and then hip-hop. But it wasn’t until my 30s where I tapped into like folk music and whether it was the early Dylan records or Woody Guthrie or Springsteen Nebraska and Johnny Cash and realize that, you know, three acoustic guitar chords and the truth can be just as heavy as anything in the Metallica catalog. And that was where I began sort of finding a different way to express myself, which has always been sort of cranked to 11, through a marshal stack and here, I’m going to attempt to reinvent the electric guitar. I realized that I had a more to say and I had a lot more to say. And it really began with — there’s — it was on that same “New York Times” article where I was at a teen homeless shelter in Hollywood and it was like a Thanksgiving talent show kind of thing and I was there. And some young man got up there. Again, a lot of problems in his life. His guitar was out of tune, his voice shook but he played as if every person’s soul in the room was at stake. And I was like, hold on. Like there’s — like do I have anything like that to say? And I found that I did.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC PLAYING)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: Let’s go back a little bit. You grew up in the Midwest. You had a father who was from Kenya. A mother who was Irish American. And the identity struggles is what intrigues me, is did you or were you identified as a black man, an African American young man and did that change over time?

MORELLO: Yes. Yes, definitely. I literally integrated the Town of Libertyville, Illinois in 1965, according to the real estate agent that helped my mom and I find our first apartment. And, you know, it was quite a journey. Yes. I was — in the town I grew up in, I was the — you know, for years, I was the only black person in town and my mom who had an excellent teaching credentials was looking for a job teaching public high school and couldn’t find a job in some of the surrounding communities because we were an interracial family. My dad did not live with us. But I was the interracial part. I was a one-year-old half African kid. And so, Libertyville offered us the — the school offered opportunity to teach there, provided that we could find a place to live. So, the real estate agent went door to door in the apartment complex across the way and explained to the other people living there, this is no normal American negro child, this like like sort of an African princeling who is going to be living there, which was — which, you know, allowed us a toehold until I was old enough to date their daughters. And then, that whole situation changed. But it was — you know, one morning when I was 13, I woke to find a noose in my family’s garage. It wasn’t the only noose I saw, you know, growing up. The N word was a thing that was a constant. People touched my hair, marveled at the color of my gums and palms and questioned openly if I was their intellectual equal throughout my growing up. It was a bucolic community with grade schools and whatnot too, but I was black, super black. Then, years later, I played in rock bands that were traditionally heard on radio stations that were traditionally reserved for music made by white artists and in magazines where — which normally featured white artists. And, you know, my speech was not stereotypically urban and there’s a wide swath of my audience that to this day is unnerved when I mention that when I self-identify as black in an interview. They’re like, this is cognitive dissonance that kicks in. Like someone who makes music like that must look like me, mustn’t they? And it’s very strange. Because my — while my skin color hasn’t changed through the years, I have changed color in the eyes of people that I encounter.

SREENIVASAN: You know, you’re successful by most measures now but come out of Harvard, moved to L.A. And I don’t have any YouTube proof of this, but I heard you were literally taking the shirt of your back to make ends meet.

MORELLO: There was exotic dancing stints between Harvard University and — between graduating from Harvard and working as the scheduling secretary for a United States senator. Yes, I did work as a stripper at national rep parties because the rent is not going to pay itself. Sorry.

SREENIVASAN: Is that in the Harvard alumni listing for you?

MORELLO: My resume has some rich eddies.

SREENIVASAN: You know, you have been talking about social justice issues for — as long as I can remember. I mean, I came into your music when I was in college and Rage Against the Machine was all the rage. And, you know, at the time, you were singing about a different presidency. You were singing about kind of a war that was raging for kind of a different reason. And I wonder, here in the past two years, so many of the lyrics that your band at the time had written found a new residence. And are you sad that they’re still relevant?

MORELLO: First of all, all credit to Zack de la Rocha, the lyricist of Rage Against the Machine and Timon Brad (ph), my brothers in arms. But — yes, I mean, I think that’s — it would with naive to assume that, you know, you make a few albums and be, you know, a socialist utopia erupts around you. And the way I look at it is, is that, you know, each day and each work of kindness and resistance is another link in the chain to try to fight for a more just and humane planet. If there’s one threat that runs through 22 albums is that the world is not going to change itself. That is up to you, like literally you, whoever’s watching or listening or whatever. And while that may sound daunting, there is great historical precedence for — on your side. And when the world has changed and progressive radical or even revolutionary ways, there’s been changed by people with no more power, influence, money, creativity or intelligence than anyone listening right now. History is not something that happens, history is something that we make, and we are agents of history. And it’s just a matter of standing up in your place, whether it’s your home, your school, or your place of work or your country to, you know, aim for, you know, the world you really want without compromise or apology. That’s what I’ve tried to — you know, what I try to do when I’m trying to have my music be about.

SREENIVASAN: You are one of the people who doesn’t hesitate from the word class in conversation and lyrics. And I wonder in the last year or so, we have seen more union struggles, for example. People — this sort of great resignation. People are also saying, maybe it’s a great reassessment that people are not willing to work the kinds of jobs for the kinds of renumeration that they have today. And I know one of your recent songs “Hold the Line” was explicitly about sort of union protests.

MORELLO: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: I mean, do you find the things have change? I mean, is it just a drop in the bucket? Where do you see in the larger arc?

MORELLO: Yes, yes. Well, I mean, this — what we were calling Striketober was like the most people on — the most individual unions and people on strike or walkouts to create unions that we’ve seen in a very, very long time. And I think that like leaning into the five-letter dirty word class is something that we have to do if we want to see any sort of real change. I think there is so much power in the working class and in unions. I’m a proud member of Musicians Local 47, a proud card carrying — red card- carrying member of the Industrial Workers of the World. The Morello’s were coal miners in Illinois. And just the idea that we should have agency in deciding in the place we work what happens there is something that should not be a foreign notion. And the way you make that happen with the simply word solidarity. That’s how it’s happened before. And I’m hopeful that there is a significant resurgence, not just in union membership but in militant union action to continue to create the kind of world that serves the people in it. Because the people who own and control the world do not deserve to. And clearly, their actions are not only endangering environmentally civilization and life on earth but in a real paycheck to paycheck way, people who are trying to make better lives for themselves and their family. And the only way to fight back against that is together.

SREENIVASAN: Right now, given the way the two-party system is structured in the United States, how do you think the labor movement or the working class get a voice at the table?

MORELLO: There’s a couple of ways to look at. Do you — how do you find — get a seat at the table or do you overturn the table entirely? Like everything — I think everything needs to be on the table now where we’re literally looking at sort of potential environmental — like a reorienting of how people are going to live based on criminal capitalist endeavors. Like are we going to be OK as a species based on how we look at the — how we weigh profit over the sustainability of humanity? I think those are things less — those are things that people have to look at. Now, as I’ve said, like I am currently — I’m stuck being guitar player. I think there are other ways where I might sort of effect change in the world, but I’m just going to keep making songs about it.

SREENIVASAN: Is the “New York Times” column kind of in the lineage? I mean, is this sort of — you’re trying to be a change agent or what are you trying to do with it?

MORELLO: Yes. Well, it’s funny you mention it. Like these records in the “New York Times,” it’s one more way to stay sane during an insane time, like sort of hang on — during an inhumane time to hang on to my humanity. I never set out to be a, you know, “New York Times” columnist and I had great trepidation about it, you know, there’s sort of mixed feelings about the venue. But it has been — you know, those articles have resonated in a way. And I hear from people every day sort of dwell outside of the normal circle of people I hear from who, you know, find something in them that’s worthwhile. And again, I will say this. This is something which I’ve also found in my music is when I was asked to do a column for — or when it was brought up to — potentially doing a column for the “New York Times,” I thought, well, I’m going to be doing, you know, a lot of research on these particular topics about Guatemala and labor unions. And then, at the end of the day, I decided to write personal politics, and that seems to have resonated in a way that rewarded my laziness.

SREENIVASAN: You know, I got to ask, during the pandemic, I mean, this might be just sort of a dad pride moment. But there was video with Nandi Bushell, who is an amazing, a phenomenal drummer and she’s in her own right, wow, right? And then, I’m watching your son play the guitar. And about a minute into the video, like, wow. This kid can shred and there’s literally you in the background, it’s like, that’s my son.

MORELLO: Yes, yes, yes.

SREENIVASAN: Like, you’re having this moment. And how did he — what happened? How did he get there?

MORELLO: Yes. What the hell happened? Like I started playing at 17. He started playing at nine and he’s also already better at nice, you know, it was a pandemic discovery. You know, the kids — no kid want to do — they don’t have anything nothing to do with — there’s instruments around the house, they don’t want anything to do with it.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

MELVIN: But during — you know, during the month or two in where the days were stretching out endlessly, he’s a fan of classic — my son, Roman, he’s a fan of like rock music a little bit. And so, I timidly suggested, you know, since we had a lot of time on our hands, would you like to learn the first three notes of Stairway to Heaven?” And he was like — you know, that didn’t sound like it would interrupt his videogame playing too much. And so, he did. And we built on these small successes. And eventually, he was coming to me and saying, now, can we learn the solo to the song? And he had an ear and aptitude for it that I had to work harder for. For him, it came a little bit more naturally. And so, now, I’m like the rhythm guitarist in the family, and he could just blow over whatever I throw at him and it just so much — he just loses himself. He was 10 years old. He just losses himself in it. And I’m just — like my job now — let me tell you, my rhythm guitar straps are together because I haven’t been allowed to play — he didn’t let me in.

SREENIVASAN: Tom Morello, thanks so much for joining us.

MORELLO: Hey, thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.

About This Episode EXPAND

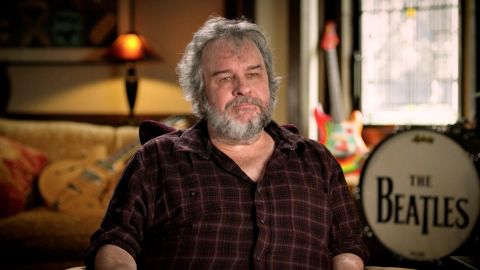

Former UN envoy Zalmay Khalilzad discusses the Taliban’s continued crackdown in Afghanistan. Director Peter Jackson explains what he learned while creating his new film “The Beatles: Get Back.” Grammy Award-winning musician Tom Morello discusses his new album and the series of essays he’s writing for the New York Times.

LEARN MORE