Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, as oil prices reach a 14-year high, the president of the European Commission, Ursula van der Leyen has said today that the E.U. has to get rid of the dependency on Russian gas, oil or coal. Our next guest says that responding with renewables is the way to both defeat Putin and prevent climate change. Bill McKibben is an award-winning environmentalist and the founder of Third Act, an organization fighting for climate and racial justice. He tells Hari Srinivasan why now is the time to transition away from fossil fuels.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

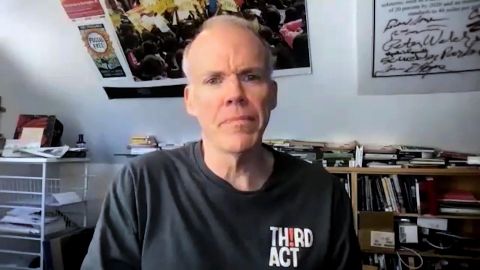

HARI SREENIVASAN, CORRESPONDENT: Christiane, thanks. Bill McKibben, thanks for joining us.

BILL MCKIBBEN, FOUNDER, THIRD ACT: Pleasure to be with you, Hari.

SREENIVASAN: As we watched this crisis in Ukraine unfold, one of the things that people are starting to think about are fossil fuels. John Kerry, our special envoy for climate, recently said that Mr. Putin has “weaponized” fossil fuels, particularly gas. “It’s related and people need to see it that way. Energy is a huge part of the geopolitics of what the options are.” So, Bill, if you could, draw the line for our audience on how the crisis in Ukraine and what we can do about it is connected to fossil fuels and oil.

MCKIBBEN: Absolutely. Against stark and dramatic backdrop of the Ukraine invasion, we’ve also had this remarkable government from the ITCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 6,000 pages demonstrating just what hot water we’re in. And the place, of course, that they’re linked is this place of fossil fuel. We know that’s what drives climate change but it’s also what drives Vladimir Putin. 60 percent of his export earnings come from oil and gas. You can check that out for yourself by looking around your house and trying to figure out what you could boycott that comes from Russia. Unless there’s an old bottle of Stolichnaya sitting in your liquor cabinet, there’s likely nothing in your house. It just produces oil and gas. And without that, he wouldn’t be able to build a plundering army, nor would he have the weapon he has used most effectively to cower Western Europe for the last 20 years, this threat to turn off the tap from his gas pipelines and let them freeze in the dark. He is entirely a creature of oil and gas. And so, ending the dependency on oil and gas would do absolutely more than anything we could possibly imagine to rein him in. At the same time, that it dealt with this other existential crisis we face, the one rising temperatures, burning forests, melting ice caps.

SREENIVASAN: You know, right now, there seems to be almost a bipartisan call for trying to put more sanctions on the export of Russian oil and gas. Now, there are probably American politics all wrapped up in this, but would it hurt Vladimir Putin more if we could restrict the oil flowing out of his country on what we do and what the world does in terms of their needs?

MCKIBBEN: It would definitely do him damage. And the reason that we haven’t done it so far is because we’re afraid that we’re so dependent on oil and gas that if the price of gas goes up, people will rebel. The oil industry would like to solve this problem, in their words, by pumping ever more oil, getting more leases. They’re talking today about going into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Camp. But of course, that doesn’t help at all. It takes years upon years to do any of that. And in any event, all it does is make the world more dependent, in the end, on fossil fuel. The obvious way to square this circle, the obvious way out is to seize this moment and use it as the choice point to head definitively in the direction of renewable energy. I think the Europeans are starting to realize this. The Germans the day after the invasion, the Bundestag passed a new law that said they would be entirely run-on renewable energy by 2035. We can help. We can make it happen much faster than that. I wrote a piece last week that’s gotten a lot of traction about the idea that we might invoke the Defense Production Act, which we invoked both Trump and Biden to help speed up the production of vaccines. In this case, to speed up the production of one of the most remarkable technologies on planet earth, the air source heat pump, which is in essence, just a reversible air conditioner that can heat and cool homes off electricity and replace the gas or oil furnace in the basement. We have spare capacity in our air conditioner companies. We could be producing millions of these just as we did with lend lease before World War II, getting them across of the Atlantic by the time November rolls around, and November will roll around again, we can have deprived Vladimir Putin of one of his strongest weapons, and in the process, started us down the path that we need to go down anyway.

SREENIVASAN: Even if we, the United States, decided to say, all right, we’re going to start — we’re going to go through this just like it was World War II, we’re going to start building heat pumps at every factory possible, it would still take months. And right you know, you have a humanitarian crisis that’s unfolding in front ever our eyes on a daily basis and there’s a reasonable chance that thousands more people are going to die in a matter of days as cities continue to be shelled by Russian forces.

MCKIBBEN: Absolutely. None of this solves that over the next few days. You know, nothing saves, perhaps, the figuring out how to get them, you know, anti-aircraft missiles or something to the Ukrainians over the next few days. But I think we better be prepared for the possibility that this is going to be a grinding and enduring conflict, and we better be positioning ourselves now to make sure that we take the steps we can so that by next winter, we’re not in precisely the same dangerous position that we found ourselves in right now. This is a perfect case for doing the things that we know we have to do anyway. And given what the IPCC told us this week, it may be the last sort of decision point like this that we get. We’re running out of time as a planet in some of the same ways that Ukraine is running out of time and room as a country. And being serious people means taking all those things on board at once and figuring out the tools we have to meet all those challenges.

SREENIVASAN: You know, one of your recent columns the headline was, “If you care about freedom, shut up about high gas prices.” Americans love their vehicles. It is still a culture that loves to drive and driving requires gasoline and we like low gas prices.

MCKIBBEN: Well, let me take issue just with one part of that statement, all of which is true except that any more driving doesn’t require gasoline. And I just wrote a piece the other day saying, you know what? We’ve now got a reasonable fleet of electric vehicles in this country. They’re all driven by people like me who are relentless borers who got how great they are, evangelists for them. So, we should — one of the things we should be doing right now is building out a kind of ride-sharing program. You remember those posters from World War II, you don’t remember them, but there were remarkable posters from World War II that said, when you ride alone, you ride with hitter. Well, in this case, when you drive gas-powered car, you drive with Putin, and we don’t need that to happen. We could be — if people need to get to the doctor or to the grocery, we should quickly be building out so at least one day a week, say, we can share what electric transportation we have. And among other things, the people who get to go for a ride will discover that these are not only affordable, they’re elegant technologies. That’s going to happen anyway. I mean, Ford starts churning out electric F- 150 pickups in the course of this spring, but we need it to happen fast, fast. Fast is always the word here.

SREENIVASAN: Why do you think it is? And you’ve worked in the environment movement for a long time, you understand messaging quite well, why are we incapable of seeing the magnitude of the climate crisis? Is it because we think it’s so far away even though we see example after example in the headlines? I mean, why doesn’t it personally affect us?

MCKIBBEN: I don’t think it is that anymore. The polling data shows that Americans understand and want action here. We can’t get our political system to do the right thing because it is so in hock to the fossil fuel industry. We’ve known this for decades, watched Congress fail again and again and again. We’ve gotten closer this time. Joe Biden’s Build Back Better Bill, which would have been the first serious climate legislation, has come within a vote of passing, but that vote belongs to Joe Manchin, who has taken more money from the fossil fuel industry than anyone in Washington, not an easy contest to win, by the way. And the return on investment’s been spectacular. He’s held up what we needed to do, and continues to, and, you know, that’s been the story in Washington over and over and over again. It’s one of the reasons why we need Biden doing things that he can do by executive action, and the Defense Production Act is a good example of that. It’s also why we need to be training as much pressure as we can on the other players here that aren’t Washington. We need to be looking hard at Wall Street. At — say at Third Act, we’re working hard to build out this campaign on the big banks to get them to stop funding the fossil fuel industry, because we can’t rely on Washington to do this. The political ability of the fossil fuel industry is so strong, their ability to turn money into votes in Congress is so powerful that at the moment, it’s overriding the strong, strong call from Americans for real action on all these problems.

SREENIVASAN: You recently wrote in an op-ed, “Imagine a Europe that ran on solar and wind power, whose cars ran on locally-provided electricity and whose homes were heated by electric air source heat pumps. That Europe would not be funding Putin’s Russia, and it would be far less scared of Putin’s Russia, it could impose every kind of sanction and keep them in place until the country buckled.” Are we there at a price point yet where renewable energies can compete and can do better?

MCKIBBEN: So, finally, we get some — to some very good news, and this really is the thing that should be letting us do what we need to do. Scientists and engineers over the last 10 years have done such a good job of dropping the price of renewable energy, sun, wind and the batteries to store them, that this is literally now the cheapest power on planet earth. There’s no longer a technological or economic obstacle, and the numbers get better with each passing quarter. Every time we double the capacity of solar power, for instance, we drop its price another 30 percent. So, we could be doing this work at rapid, rapid, rapid pace. The only reasons we’re not are some toxic combination of inertia, which perhaps Vladimir Putin is helping us overcome, and vested interest, and that’s why we have to build movements to try and break the power of the fossil fuel industry before they break everything else.

SREENIVASAN: You mentioned it earlier in the conversation, the IPCC report. This is the latest in a string of reports that have sounded more and more, or I should say, sounded the alarm louder and louder. What did you hear the most from that report?

MCKIBBEN: With each new iteration of these reports, the message gets more dire. As they said in the final sentence of these 6,000-page report, they said, the window is now closing. Essentially, we’ve been told by the IPCC that we need to cut emissions in half by 2030 if we’re going to meet those targets we set in Paris. 2030 is, as of last week, seven years and 10 months away. We’re not used to time tests in our political system. We’re used to debating the same things forever and ever and making incremental progress. That’s not how this one works. Once the Arctic’s melted, no one’s got a plan for freezing it back again. So, we better do what we need to do, that’s what the IPCC is telling us. And you can sense the sort of desperation beginning to come off these climate scientists. In fact, the next day, a bunch of them said, you know what? We’re going to go on strike. We’re not going to just keep producing these IPCC reports year after year forever, forever volunteering to do this work because nobody’s paying attention. We need you to pay attention. And that note of desperation, you know, scientists, by their nature, are not political animals. That note of desperation should be attended to.

SREENIVASAN: Just recently, there was an attack by Russian forces on a nuclear plant which got everybody very concerned. Fortunately, the fire that was reported had been put out, but should we be reconsidering nuclear energy as part of the mix of renewables?

MCKIBBEN: We definitely — I think it’s pretty clear that we should try and keep the nuclear plants that we have built and are operating open when we can with some margin of safety. Though, of course, the experience in the Ukraine is a reminder of how narrow that margin is. That was truly a scary moment. I don’t think that nuclear power is probably going to play a huge role in the future going forward, simply because it’s extremely expensive. Part of the reason it’s expensive is because you have to build these, you know, facilities with all the kind of risks that we’ve seen in mind, whereas, you know, if you shell a solar panel, what do you have in a pile of broken glass at the end. The reason that we’re going to move to renewable energy so decisively is because the cost of it is going like this, down, down, down, down, down. The cost of nuclear power continues to go up and up. Maybe someday people will invent smaller modular reactors or fusion reactors or — and we will be able to take down the wind turbines and solar panels and replace them with something else. But for now, wind, sun and batteries are the off-the- shelf technologies that make economic sense and now, we know just how much political sense they make, too.

SREENIVASAN: Do you think that this crisis, this war in Ukraine, has the ability to make people rethink climate policy in countries like the United States who might not be affected nearly as much as European nations who are so dependent on Russian oil and gas?

MCKIBBEN: Let’s hope so. Let’s hope that people can see that the burning buildings in the Ukraine and the burning forests in California have a lot of things in common, and that the solutions, at least some of them, are very similar, that we need to make big transitions. And if we do, we remove the power of autocrats everywhere. You know, it’s not just Vladimir Putin. They all derive their power from the fact that fossil fuel is concentrated in a few scattered places around the world. The people who control them end up with way more power than they deserve, right down to the Koch Brothers, our biggest oil and gas barons in this country. Sun and wind come from everywhere. And so, the world that we inhabit, when we run it on sun and wind, is a different kind of world, one that we really should want to move to for all kinds of reasons.

SREENIVASAN: Bill McKibben, thanks for joining us.

MCKIBBEN: Hari, what a pleasure.

About This Episode EXPAND

Oleksandr Syenkevych, mayor of Mykolaiv, Ukraine, gives an update on destruction in his city. Ambassador Julianne Smith discusses NATO’s evolving plans to deter Russia. Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov discusses the role of art during times of war. Bill McKibben explains how climate policy can be used to fight autocracy.

LEARN MORE